Perceptions of Community Safety in West Auckland.Pdf (1.582Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert-Eden Local Board Progress and Achievements Report July 2016-December 2017

Albert-Eden Local Board Progress and Achievements Report July 2016-December 2017 The view from Owairaka/Te Ahikā Roa o Raka/Mt Albert towards Maungawhau/Mt Eden and Te Kōpuke/Titikōpuke/Mt St John Progress and Achievements Report July 2016-December 2017 3 Table of contents 1 Message from the chair ................................................................................................. 4 2 Albert-Eden Local Board members ............................................................................... 5 3 Achievements ................................................................................................................ 6 4 Proud, connected and secured communities ................................................................ 7 5 A better and bigger range of recreational experiences ................................................ 11 6 Thriving town centres and a growing local economy ................................................... 15 7 A community that values its environment .................................................................... 18 8 Our heritage is cherished and protected ..................................................................... 20 9 People can move safely and easily around Albert-Eden ............................................. 22 10 Consultation, engagement and representation ............................................................ 24 On the cover: Performers at the Albert-Eden Schools Cultural Festival 2017 4 Progress and Achievements Report July 2016 – December 2017 1 Message from -

Albert-Eden Local Board Progress and Achievements Report

Albert-Eden Local Board Progress and Achievements Report January 2018 – June 2019 Dreamcatcher at Mount Albert town centre streetscape opening, May 2018 3 Table of contents Message from the Chair....................................................................................................... 4 Albert-Eden Local Board members ...................................................................................... 5 Local boards ........................................................................................................................ 6 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 7 Outcome 1: Albert-Eden has a strong sense of community ................................................. 8 Outcome 2: Our parks are enjoyed by all........................................................................... 14 Outcome 3: Our community spaces are well used by everyone ........................................ 19 Outcome 4: Albert-Eden has thriving town centres and a growing local economy ............. 22 Outcome 5: Travelling around Albert-Eden is safe and easy ............................................. 26 Outcome 6: Our natural and cultural heritage is valued ..................................................... 29 Outcome 7: We respect and protect our environment ....................................................... 31 Consultation, engagement and representation .................................................................. 35 On -

Attachment 5 Local Board Resolutions

Attachment 5 Local Board Resolutions Contents Albert Eden ............................................................................................................................. 2 Devonport-Takapuna .............................................................................................................. 5 Franklin ................................................................................................................................... 7 Great Barrier ......................................................................................................................... 13 Henderson-Massey ............................................................................................................... 17 Hibiscus and Bays ................................................................................................................ 21 Howick .................................................................................................................................. 28 Kaipatiki ................................................................................................................................ 31 Mangere-Otahuhu ................................................................................................................. 38 Manurewa ............................................................................................................................. 42 Maungakiekie-Tamaki ........................................................................................................... 49 Orakei .................................................................................................................................. -

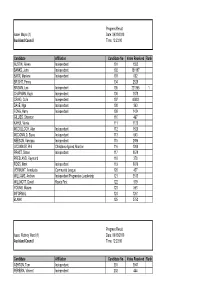

Auckland Progress Results

Progress Result Issue: Mayor (1) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank AUSTIN, Aileen Independent 101 1552 BANKS, John Independent 102 161167 BARR, Marlene Independent 103 692 BRIGHT, Penny 104 2529 BROWN, Len Independent 105 2213651 CHAPMAN, Hugh Independent 106 1878 CRAIG, Colin Independent 107 40483 DAVE, Nga Independent 108 840 FONG, Harry Independent 109 1434 GILLIES, Shannon 110 467 KAHUI, Vinnie 111 1120 MCCULLOCH, Alan Independent 112 1520 MCDONALD, Steve Independent 113 643 NEESON, Vanessa Independent 115 2885 O'CONNOR, Phil Christians Against Abortion 116 1209 PRAST, Simon Independent 117 3578 PRESLAND, Raymond 118 278 ROSS, Mark Independent 119 3076 VERMUNT, Annalucia Communist League 120 427 WILLIAMS, Andrew Independent Progressive Leadership 121 3813 WILLMOTT, David Roads First 122 519 YOUNG, Wayne 123 553 INFORMAL 124 1261 BLANK 125 3752 Progress Result Issue: Rodney Ward (1) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank ASHTON, Tom Independent 201 3941 PEREIRA, Vincent Independent 202 444 ROSE, Christine 203 5553 WEBSTER, Penny Independent 204 8063 1 INFORMAL 205 21 BLANK 206 701 Progress Result Issue: Albany Ward (2) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank BALOUCH, Uzra Independent 221 736 BELL, Rodney Independent 222 3151 BRADLEY, Ian Independent 223 5273 CONDER, Laurie Independent 224 1419 COOPER, David Independent 225 2821 COOPER, -

AVONDALE Town Centre Regeneration

AVONDALE Town centre regeneration High Level Project Plan – November 2017 ABBREVIATIONS ACPL Auckland Council Property Ltd AT Auckland Transport BID Business improvement district CCO Council-controlled organisation the council Auckland Council CRL City Rail Link HLC HLC (formerly Hobsonville Land Company) HLPP High Level Project Plan HNZ Housing New Zealand LTP Long-term Plan Panuku Panuku Development Auckland SOI Statement of Intent 2 AVONDALE HLPP CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 5 6 OPPORTUNITIES 37 FIGURES 1.1 Mihi 8 Figure 1: Project area 25 7 STRATEGIC MOVES 41 1.2 Shaping spaces for Aucklanders to love 9 7.1 Move 1: Enliven the heart of Avondale town centre 43 Figure 2: Unitary Plan zoning 27 1.3 Panuku – Who we are 10 7.2 Move 2: Create high-quality 46 Figure 3: Key opportunities 39 1.4 Why Avondale? 11 residential neighbourhoods Figure 4: Move 1: Enliven the heart 43 2 PURPOSE OF THIS PLAN 13 7.3 Move 3: Strengthen connections 48 of Avondale town centre with the town centre 3 VISION 17 Figure 5: Move 2: Create high quality 46 7.4 Move 4: Foster the growth of local businesses 50 residential neighbourhoods 4 CONTEXT 21 8 PROPOSED IMPLEMENTATION 53 4.1 Background 22 Figure 6: Move 3: Strengthen connections 48 8.1 Development strategy 54 4.2 Mana whenua 22 with the town centre 8.2 Total value creation 54 4.3 Cultural narrative 23 Figure 7: Move 4: Foster the growth of local businesses 50 8.3 Project team structure and leadership 55 4.4 Project area 24 8.4 Timeframes and phasing 55 4.5 Planning 26 8.5 Outcomes monitoring 56 4.6 Cultural and -

TE PŪRONGO Ā TAU 2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2 Acknowledgement – Ngā Mihi

TE PŪRONGO Ā TAU 2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2 Acknowledgement – Ngā mihi Fred Holloway Kaumatua We continue to be grateful for, and honoured by the contribution of Matua Fred Holloway as our Kaumatua. As well as attending and officiating at a large number of public events, ‘Papa Fred’ attends our Board meetings and always provides wise counsel and important insights. We are much richer for this contribution. E Matua Ka nui ngā mihi ki a koe Tēnā Koe Contents 2 Vision – Pae Tawhiti kia Ita 3 Acknowledgement – Ngā mihi 3 Contents – Rārangi kaupapa 4 Board Chair report – Te Pūrongo a Te Kaihautū o Community Waitakere 7 Executive Officer report – Te Pūrongo a Te Kaiwhakahaere Matua 9 Our people – Tātou ngā Kairīnga 12 Introduction – Kupu Whakataki 16 Neighbourhood development – Whakawhanake Kiritata 24 Training workshops – Whakangungu mahi 25 Developing Grass roots leadership – Mana whakatipu hapori 26 Building community networks and connections – Whakapakari whānaungatanga 28 Supporting social and environmental campaign issues – Tau aa toko taiao 30 Engaging with community groups in environmental restoration – Kōtuitui tāngata ki te Taiao 35 Initiating environmental education and citizen science – Whakaara mātauranga Pūtaiao 38 Ethkick West 39 Thank you to our friends - Tēnā koutou 40 Supporters – Mei kore ko koutou, ka kore mātou e taea! We encourage you to use the e-version on: www.communitywaitakere.org.nz Printed on paper certified by FSC to be from responsible sources 3 Board Chair report Ngā mihi nui kia koutou katoa Nau mai, haere mai ki tēnei hui Chair’s report for Community Waitakere 2019. Looking back over the last 12 months, it has been an extraordinarily busy year with some fantastic highlights. -

Ward and Local Board Boundary Maps and Relevant Population

Current ward population. This is based on population statistics provided through the Local Government Commission for the purpose of reviewing our boundaries. The statistics are a 2017 estimate based on the 2013 census. The council has proposed changes to the Local Government Commission to reduce the non- compliance in the Waitematā and Gulf ward Per cent Population Difference difference per from from Ward Population Members member quota quota Rodney Ward 64,300 1 64,300 -18,560 -22.40 Albany Ward 169,800 2 84,900 2,040 2.46 North Shore Ward 156,800 2 78,400 -4,460 -5.38 Waitākere Ward 176,500 2 88,250 5,390 6.50 Waitematā and Gulf Ward 119,100 1 119,100 36,240 43.74 Whau Ward 84,700 1 84,700 1,840 2.22 Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward 172,200 2 86,100 3,240 3.91 Ōrākei Ward 91,500 1 91,500 8,640 10.43 Maungakiekie-Tāmaki Ward 79,700 1 79,700 -3,160 -3.81 Howick Ward 150,200 2 75,100 -7,760 -9.37 Manukau Ward 168,900 2 84,450 1,590 1.92 Manurewa-Papakura Ward 148,900 2 74,450 -8,410 -10.15 Franklin Ward 74,600 1 74,600 -8,260 -9.97 Total 1,657,200 20 82,860 Current local board population Statistics supplied through the Local Government Commission. Population Board Population Members per member Rodney 64,300 9 7,144 Hibiscus and Bays 104,500 8 13,063 Upper Harbour 65,300 6 10,883 Kaipātiki 94,000 8 11,750 Devonport-Takapuna 62,800 6 10,467 Henderson-Massey 122,300 8 15,288 Waitākere Ranges 54,200 6 9,033 Great Barrier 1,000 5 200 Waiheke 9,630 5 1,926 Waitematā 108,500 7 15,500 Whau 84,700 7 12,100 Albert-Eden 109,200 8 13,650 Puketāpapa 63,000 6 10,500 Ōrākei 91,500 7 13,071 Maungakiekie-Tāmaki 79,700 7 11,386 Howick 150,200 9 16,689 Māngere-Ōtāhuhu 81,100 7 11,586 Ōtara-Papatoetoe 87,800 7 12,543 Manurewa 94,500 8 11,813 Papakura 54,500 6 9,083 Franklin 74,600 9 8,289 Total 1,657,330 Local board subdivisions The following table shows those boards with subdivisions, and their current population. -

Annexure a to Procedural Minute 6

Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan Appendix 3.1 Schedule for the Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Owner/ Approral/ Sub#/ Point Name Theme Topic Subtopic Summary Submission Type Support Evidence Comentary Investigate 81 Mt Royal Rd, Mt Albert, and all other lava cave Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the entrances, for inclusion in the SEA schedule [Note - relates to Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features ONFs. Refer to Albert-Eden Local Board Views, Volume 26, page 5716-3481 Auckland Council Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add 30/103]. Local Government no iv Investigate the 'Spring', located under Crystal Motors at 11 Ruru Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the St, Eden Terrace, for inclusion in the SEA schedule [Note - Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features relates to ONFs. Refer to Albert-Eden Local Board Views, Volume 5716-3482 Auckland Council Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add 26, page 30/103]. Local Government no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Include volcanic features in former outlying district such as Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Franklin within the PAUP including Pukekohe Hill, Puni Mountain, 4485-11 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add Pukekohe East crater. Key Stakeholder no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Include Pukekohe Hill and Puni Mountain as outstanding natural 4485-13 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add features. Key Stakeholder no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Apply V1 and V2 overlays to volcanic reserves and surrounding 4485-21 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add Includeareas. -

Auckland Council ALUPIS Mario

ID Council Issue Last Name First Names Affiliation 3764 AC Mayor - Auckland Council ALUPIS Mario <none> 1537 AC Mayor - Auckland Council AUSTIN Aileen Independent 6141 AC Mayor - Auckland Council BRIGHT Penny Independent 6156 AC Mayor - Auckland Council BROWN Patrick Communist League 1385 AC Mayor - Auckland Council CHEEL Tricia STOP 211 AC Mayor - Auckland Council CRONE Vic Independent 2597 AC Mayor - Auckland Council GOFF Phil Independent 420 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HAY David Independent 6131 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HENETI Alezix <none> 663 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HOLLAND Adam John Auckland Legalise Cannabis 1416 AC Mayor - Auckland Council MARTIN Stan Independent 6181 AC Mayor - Auckland Council NGUYEN Binh Thanh Independent 703 AC Mayor - Auckland Council O'CONNOR Phil Christians Against Abortion 1622 AC Mayor - Auckland Council PALINO John Independent 398 AC Mayor - Auckland Council SWARBRICK Chloe Independent 1370 AC Mayor - Auckland Council THOMAS Mark Independent 1239 AC Mayor - Auckland Council YOUNG Wayne <none> 1618 AC Albany Ward BENSCH John Independent 6130 AC Albany Ward HENETI Alezix <none> 6214 AC Albany Ward LOWE Graham Auckland Future 1389 AC Albany Ward WALKER Wayne Putting People First 688 AC Albany Ward WATSON John Putting People First 6213 AC Albany Ward WHYTE Lisa Auckland Future 1629 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward CASEY Cathy City Vision 432 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward FLETCHER Christine C&R - Communities & Residents 1433 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward HARRIS Rob Auckland Future 2579 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill -

Local Board Information and Agreements Draft Long-Term Plan 2012-2022

DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS About this volume About this volume This is Volume Four of the four volumes that make up the draft LTP. It is set out in two parts, one which provides background on the role of local boards, their decision-making responsibilities and some general information about local board plans and physical boundaries. The second part contains the individual local board agreements for all 21 local boards, which contain detailed information about local activities, services, projects and programmes and the corresponding budgets for the period 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2013. Here we have also included additional information like ten-year budgets for each board and a capital projects list. What this volume covers: the status of draft local board agreements how to have your say during the public consultation period an overview of the local boards local board activities information on the development of local board plans and agreements local board financial information including a consolidated statement of expenditure on local activities about each local board, with an overview of the local board including their strategic priorities and a message from the chairperson draft local board agreements for each local board covering scope of activities levels of service and performance measures local activities including key initiatives and projects expenditure and funding notes to the local board agreements contact details, how to contact your local board, including individual contact details for each local board member an appendix to each Local Board information section which includes their expenditure statements and capital projects for the ten-year period 2012 to 2022. -

2019 Local Elections Preliminary Results – Mayor, Local Board

Result: LGE 2019 - Preliminary Result Type: Preliminary Candidates sorted by: Votes Generated on: Sunday 13 October 2019 Elections: Auckland Council Election: 01 - Auckland Council Issue: Mayor - Auckland Council Number of vacancies: 1 Candidate Voting ID Candidate Name Affiliation Votes Received Rank 105 GOFF, Phil Independent 176599 1 118 TAMIHERE, John JT for Mayor.co.nz 79551 111 LORD, Craig Independent 29032 108 HONG, John Independent 15965 109 JOHNSTON, Ted 15401 119 VAUGHAN, Peter 6127 102 COOTE, Michael Independent 5530 101 CHEEL, Tricia STOP Trashing Our Planet 4013 114 O'CONNOR, Phil Christians Against Abortion 3917 110 KRUGER, Susanna Justice for Families 2840 104 FORDE, Genevieve 2824 115 SAINSBURY, Tom Independent 2804 116 SNELGAR, Glen Old Skool 2576 117 STOPFORD, Tadhg Tim The Hemp Foundation 2380 107 HENRY, Jannaha 2356 103 FEIST, David John LiftNZ 2259 112 MADDERN, Brendan Bruce Independent 1430 121 YOUNG, Wayne Virtual Homeless Community 1388 120 VERMUNT, Annalucia Communist League 1030 113 NGUYEN, Thanh Binh Independent 941 106 HENETI, Alezix 507 122 Informal 1558 123 Blank 6982 Election: 01 - Auckland Council Issue: Albany Ward Number of vacancies: 2 Candidate Voting ID Candidate Name Affiliation Votes Received Rank 224 WATSON, John Putting People First 28073 1 223 WALKER, Wayne Putting People First 24371 2 222 PARFITT, Julia Independent 19884 221 HENETI, Alezix 3167 225 Informal 23 226 Blank 2989 Election: 01 - Auckland Council Issue: Albert-Eden-Puketāpapa Ward Number of vacancies: 2 Candidate Voting ID Candidate -

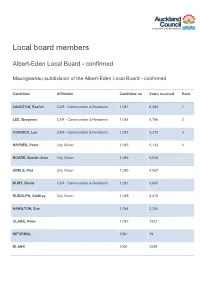

Local Board Members

Local board members Albert-Eden Local Board - confirmed Maungawhau subdivision of the Albert-Eden Local Board - confirmed Candidate Affiliation Candidate no Votes received Rank LANGTON, Rachel C&R - Communities & Residents 1,087 6,380 1 LEE, Benjamin C&R - Communities & Residents 1,088 5,786 2 CORRICK, Lee C&R - Communities & Residents 1,083 5,278 3 HAYNES, Peter City Vision 1,085 5,142 4 HOARE, Brodie-Jean City Vision 1,086 5,046 UBELS, Piet City Vision 1,090 4,067 BURT, David C&R - Communities & Residents 1,081 3,960 RUDOLPH, Godfrey City Vision 1,089 3,876 HAMILTON, Sue 1,084 2,268 CLARK, Peter 1,082 1522 INFORMAL 1091 19 BLANK 1092 2089 Owairaka subdivision of Albert-Eden Local Board - confirmed Candidate Affiliation Candidate no Votes received Rank WATSON, Margi City Vision 1078 7292 1 ROSE, Jessica City Vision 1077 7020 2 FRYER, Glenda City Vision 1072 6431 3 EASTE, Graeme City Vision 1071 6150 4 POIRIER, Monique C&R - Communities & Residents 1076 4073 JOHNSON, Jeffrey C&R - Communities & Residents 1073 3827 LO, Callum C&R - Communities & Residents 1074 3582 OLSEN, Angela C&R - Communities & Residents 1075 3297 INFORMAL 1079 12 BLANK 1080 1634 Devonport-Takapuna Local Board - confirmed Candidate Affiliation Candidate no Votes received Rank COHEN, Mike Community Before Council 625 8687 1 WOOD, George Team George Wood 638 8099 2 GILLON, Grant Shore Action 628 7640 3 O'CONNOR, Jan Shore Action 633 6688 4 SHEEHY, Michael Team George Wood 635 5642 5 MCKENZIE, Jennifer Team George Wood 632 5375 6 DEANS, Trish Shore Action 626 5262 REVELL,