Action Statement Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plaucident Planigale Version Has Been Prepared for Web Publication

#52 This Action Statement was first published in 1994 and remains current. This Plaucident Planigale version has been prepared for web publication. It Planigale gilesi retains the original text of the action statement, although contact information, the distribution map and the illustration may have been updated. © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2003 Published by the Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Plaucident Planigale (Planigale gilesi) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) 8 Nicholson Street, (Illustration by John Las Gourgues) East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia Description and Distribution these regions it is associated with habitats The Paucident Planigale (Planigale gilesi near permanent water or areas that are This publication may be of periodically flooded, such as bore drains, assistance to you but the Aitken 1972) is a small carnivorous creek floodplains or beside lakes (Denny State of Victoria and its marsupial. It was first described in 1972, employees do not guarantee and named in honour of the explorer Ernest 1982). that the publication is Giles who, like this planigale, was an In Victoria, it is found only in the north-west, without flaw of any kind or 'accomplished survivor in deserts' (Aitken adjacent to the Murray River downstream is wholly appropriate for 1972). from the Darling River (Figures 1 and 2). It your particular purposes It is distinguished by its flattened was first recorded here in 1985, extending its and therefore disclaims all triangular head, beady eyes and two known range 200 km further south from the liability for any error, loss most southern records in NSW (Lumsden et or other consequence which premolars on each upper and lower jaw al. -

A Recent Report by the NSW Nature Conservation

BULLDOZING OF BUSHLAND NEARLY TRIPLES AROUND MOREE AND COLLARENEBRI AFTER SAFEGUARDS REPEALED IN NSW The Nature Conservation Council is a movement of passionate people who want nature in NSW to thrive. We represent more than 160 organisations and thousands of people who share this vision. Together, we are a powerful voice for nature. WWF has a long and proud history. We’ve been a leading voice for nature for more than half a century, working in 100 countries on six continents with the help of over five million supporters. WWF partners with governments, businesses, communities and individuals to address a range of pressing environmental issues. Our work is founded on science, our reach is international and our mission is exact – to create a world where people live and prosper in harmony with nature. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is acknowledged. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written consent. Citation: WWF-Australia and Nature Conservation Council of NSW (2018). In the spirit of respecting and strengthening partnerships with Australia’s First Peoples, we acknowledge the spiritual, social, cultural and economic importance of lands and waters to Aboriginal peoples. We offer our appreciation and respect for the First Peoples’ continued connection to and responsibility for land and water in this country, and pay our respects to First Nations Peoples and -

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA updates. for Edition 4th Editors See A.C. Robinson K.D. Casperson Biological Survey and Research Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia M.N. Hutchinson South Australian Museum Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts, South Australia 2000 i EDITORS A.C. Robinson & K.D. Casperson, Biological Survey and Research, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage. G.P.O. Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001 M.N. Hutchinson, Curator of Reptiles and Amphibians South Australian Museum, Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts. GPO Box 234, Adelaide, SA 5001updates. for CARTOGRAPHY AND DESIGN Biological Survey & Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage Edition Department for Environment and Heritage 2000 4thISBN 0 7308 5890 1 First Edition (edited by H.J. Aslin) published 1985 Second Edition (edited by C.H.S. Watts) published 1990 Third Edition (edited bySee A.C. Robinson, M.N. Hutchinson, and K.D. Casperson) published 2000 Cover Photograph: Clockwise:- Western Pygmy Possum, Cercartetus concinnus (Photo A. Robinson), Smooth Knob-tailed Gecko, Nephrurus levis (Photo A. Robinson), Painted Frog, Neobatrachus pictus (Photo A. Robinson), Desert Goby, Chlamydogobius eremius (Photo N. Armstrong),Osprey, Pandion haliaetus (Photo A. Robinson) ii _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS -

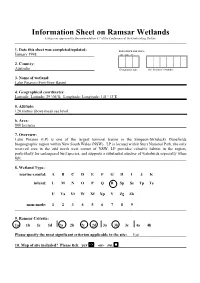

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. January 1998 DD MM YY 2. Country: Australia Designation date Site Reference Number 3. Name of wetland: Lake Pinaroo (Fort Grey Basin) 4. Geographical coordinates: Latitude: Latitude: 29º06’S; Longitude: Longitude: 141º13’E 5. Altitude: 120 metres above mean sea level. 6. Area: 800 hectares 7. Overview: Lake Pinaroo (LP) is one of the largest terminal basins in the Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields biogeographic region within New South Wales (NSW). LP is located within Sturt National Park, the only reserved area in the arid north west corner of NSW. LP provides valuable habitat in the region, particularly for endangered bird species, and supports a substantial number of waterbirds especially when full. 8. Wetland Type: marine-coastal: A B C D E F G H I J K inland: L M N O P Q R Sp Ss Tp Ts U Va Vt W Xf Xp Y Zg Zk man-made: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 9. Ramsar Criteria: 1a 1b 1c 1d 2a 2b 2c 2d 3a 3b 3c 4a 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: 1(a) 10. Map of site included? Please tick yes ⌧ -or- no. 11. Name and address of the compiler of this form: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Conservation Assessment and Planning Division PO BOX 1967 Hurstville NSW 2220 Phone: 02 9585 6477 AUSTRALIA Fax: 02 9585 6495 12. -

Nantawarrina IPA Vegetation Chapter

Marqualpie Land System Biological Survey MAMMALS D. Armstrong1 Records Available Prior to the 2008 Survey Mammal data was available from four earlier traps (Elliots were not used during the first year), Department of Environment and Natural Resources compared to the two trap lines of six pitfalls and 15 (DENR) surveys which had some sampling effort Elliots, as is the standard for DENR surveys. within the Marqualpie Land System (MLS). These sources provided a total of 186 records of 16 mammal The three Stony Deserts Survey sites were located species (Table 18). These surveys were: peripheral to the MLS and in habitat that is unrepresentative of the dunefield, which dominates the • BS3 – Cooper Creek Environmental Association survey area. Therefore, only data collected at the 32 Survey (1983): 9 sites. Due to the extreme comparable effort survey sites sampled in 2008 is variability in sampling effort and difficulty in included in this section. All other data is treated as identifying site boundaries, this is simply the supplementary and discussed in later sections. number of locations for which mammal records were available. The 24 species recorded at sites consisted of five • BS41 – Della and Marqualpie Land Systems’ native rodents, five small dasyurids (carnivorous/ Fauna Monitoring Program (1989-92): 10 sites. insectivorous marsupials), five insectivorous bats, the • BS48 – Rare Rodents Project: one opportunistic Short-beaked Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), Red sighting record from 2000. Kangaroo (Macropus rufus) and Dingo (Canis lupus • BS69 – Stony Deserts Survey (1994-97): 3 sites. dingo), and six introduced or feral species. As is the case throughout much of Australia, particularly the An additional 20 records of seven mammal species arid zone, critical weight range (35g – 5.5kg) native were available from the SA Museum specimen mammal species, are now largely absent (Morton collection. -

Assessing the Sustainability of Native Fauna in NSW State of the Catchments 2010

State of the catchments 2010 Native fauna Technical report series Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Assessing the sustainability of native fauna in NSW State of the catchments 2010 Paul Mahon Scott King Clare O’Brien Candida Barclay Philip Gleeson Allen McIlwee Sandra Penman Martin Schulz Office of Environment and Heritage Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Technical report series Native vegetation Native fauna Threatened species Invasive species Riverine ecosystems Groundwater Marine waters Wetlands Estuaries and coastal lakes Soil condition Land management within capability Economic sustainability and social well-being Capacity to manage natural resources © 2011 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage The State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this technical report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to -

Nederlandse Namen Van Eierleggende Zoogdieren En

Blad1 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q 1 Nederlandse namen van Eierleggende zoogdieren en Buideldieren 2 Prototheria en Metatheria Monotremes and Marsupials Eierleggende zoogdieren en Buideldieren 3 4 Klasse Onderklasse Orde Onderorde Superfamilie Familie Onderfamilie Geslacht Soort Ondersoort Vertaling Latijnse naam Engels Frans Duits Spaans Nederlands 5 Mammalia L.: melkklier +lia Mammals Zoogdieren 6 Prototheria G.: eerste dieren Protherids Oerzoogdieren 7 Monotremata G.:één opening Monotremes Eierleggende zoogdieren 8 Tachyglossidae L: van Tachyglossus Echidnas Mierenegels 9 Zaglossus G.: door + tong Long-beaked echidnas Vachtegels 10 Zaglossus bruijnii Antonie Augustus Bruijn Western long-beaked echidna Échidné de Bruijn Langschnabeligel Equidna de hocico largo occidental Gewone vachtegel 11 Long-beaked echidna 12 Long-nosed echidna 13 Long-nosed spiny anteater 14 New Guinea long-nosed echidna 15 Zaglossus bartoni Francis Rickman Barton Eastern long-beaked echidna Échidné de Barton Barton-Langschnabeligel Equidna de hocico largo oriental Zwartharige vachtegel 16 Barton's long-beaked echidna 17 Z.b.bartoni Francis Rickman Barton Barton's long-beaked echidna Wauvachtegel 18 Z.b.clunius L.: clunius=stuit Northwestern long-beaked echidna Huonvachtegel 19 Z.b.diamondi Jared Diamond Diamond's long-beaked echidan Grootste zwartharige vachtegel 20 Z.b.smeenki Chris Smeenk Smeenk's long-beaked echidna Kleinste zwartharige vachtegel 21 Zaglossus attenboroughi David Attenborough Attenborough's long-beaked echidna Échidné d'Attenborough Attenborough-Lanschnabeligel -

Expedition Witjira

uX61 Scientific Expedition Group with National Parks and Wildlife and Department for Environmentand Heritage E EXPEDITIONWITJIRA INTERIM REPORT 12TH 26TH July 2003 A biodiversity surveyof the mound springs and surrounding area. Photo D Noack Pogona viticeps enjoying the view Scientific Expedition Group(SEG) with National Parks and Wildlife(NPWS) and Department of Environmentand Heritage (DEH) EXPEDITIONWITJIRA Interim Report 12TH 26TH July 2003 EditorsJanet Furler andRichard Willing expeditions to placesof scientific interestin South The Scientific ExpeditionGroup organises work under the offer training and experiencein scientific field Australia. Expeditions In addition to training,expeditions supervision of scientistsand experienced fieldworkers. For further information,visit our website at: aim to produce resultsof scientific interest. www.community webs .org/ScientificExpeditionGroup/ environmentand heritage WESTERN MINING ARID AREAS CATCHMENT WATER CORPORATION MANAGEMENT BOARD For copies of thisreport contact SEG Secretary, PO Box 501, Unley5061, Email segcomms @telstra.corn ISBN 09588508 -5 -2 Copyright ScientificExpedition Group July2006. Material in thisreport may be quoted andused for databases withacknowledgementsto SEG. Summary Group major collaboration betweenthe Scientific Expedition Expedition Witjira 2003 was a Parks and Wildlife Environment and Heritage(DEH) and National (SEG), Department for conduct a biodiversity surveyof the area, Service (NPWS). Themain objective was to differences betweensprings with original particularly -

Regional Species Conservation Assessments DEWNR Outback

Regional Species Conservation Assessments DEWNR Outback Region Complete Dataset for Fauna Assessments May 2013 Species listed per Class (Mammalia, Aves, Reptilia, Amphibia, Osteichthyes) d e e n r r e o o r c c T S + S s s s U d d u u u O t t n n t a a e e a n 2 E t t t r r i E D S S T T S m D D l l l l l k O E O _ 2 a a a a a C t R V C n n n n n m n N S R o o o o o k e S k i i i i i E U _ c Q c U l S g g g g g T S l e a E T e e e e e N A B A R b S A t T R R R R R O _ _ O I T u A C S U U I T S G K K K K K S O T O O S M E T C C C C C _ _ n n C A i i R O C n n A A A A A A i i L _ D N L L A e I _ _ B B B B B U r C E O A A T T T T T O O P O T o W T T X B f f _ U U U U U A c P A o o P A CLASS NAME FAMILY NAME FAMILY COMMON NAME NSX CODE SPECIES COMMON NAME O O O O O O O S M T E N D T T % A A 1 2 MAMMALIA TACHYGLOSSIDAE Echidnas W01003 Tachyglossus aculeatus Short-beaked Echidna 2010 1445 246 17.02 186 176 LC 1 0 0.3 1.3 2 3 MAMMALIA MYRMECOBIIDAE Numbat M01086 Myrmecobius fasciatus Numbat VU E 1936 3 3 100.00 1 RE 7 7.0 3 4 MAMMALIA DASYURIDAE Dasyurids C04277 Dasycercus blythi (Mulgara) Mulgara VU E 2007 13 12 92.31 11 10 RE 7 7.0 4 5 MAMMALIA DASYURIDAE Dasyurids C01021 Dasycercus byrnei Kowari VU V 2011 131 131 100.00 44 37 VU 4 - 0.4 4.4 5 6 MAMMALIA DASYURIDAE Dasyurids K09005 Dasycercus cristicauda (Ampurta) Ampurta EN 2011 211 209 99.05 141 132 LC 1 0 0.3 1.3 6 7 MAMMALIA DASYURIDAE Dasyurids U01010 Dasyurus geoffroii Western Quoll VU E 1899 9 2 22.22 2 RE 7 7.0 7 10 MAMMALIA DASYURIDAE Dasyurids Q01036 Pseudantechinus macdonnellensis -

The Foraging Behaviour of the Arid Zone Herbivores the Red Kangaroo (Macropus Rufus) and the Sheep (Ovis Aries) and Its Role In

The Foraging Behaviour of the Arid Zone Herbivores the Red Kangaroo (Macropus rufus) and the Sheep (Ovis aries) and its Role in Their Competitive Interaction, Population Dynamics and Life-History Strategies by Steven McLeod A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales February, 1996 Summary (1) The foraging behaviours of the arid zone herbivores the red kangaroo (Macropus rufus) and the sheep ( Ovis aries) were studied over a four year period in arid western New South Wales. These herbivores are subject to wide temporal variation in food abundance and quality. I examined their foraging behaviour to test the hypothesis that their population dynamics could be explained from the basis of their food and energy intake. (2) Previous studies of these herbivores have hypothesised that they compete exploitatively for food. The results of these studies have been suggestive but not conclusive. I conducted a controlled removal experiment to examine the hypothesis that these herbivores interspecifically compete. There were three treatments (x2 replicates); i) sheep only, ii) red kangaroos only and iii) sheep and red kangaroos. The productivity of each herbivore in the presence and absence of its putative competitor were compared to determine any competitive effect. The results indicated that exploitative competition between sheep and red kangaroos occurs rarely. Interference competition is more common. Red kangaroos were found to consistently avoid areas used by sheep. The effect of interference competition sheep productivity was less clear and appeared to be associated with unusual circumstances such as the combination of low food availability and high red kangaroo density. -

Sturt National Park – Biodiversity Checklist

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity a trapping programme as part of biodiversity monitoring where they are harmlessly caught in small aluminium box traps laced with Checklist peanut butter and oats or in a pitfall with a soft landing on pillow stuffing. Small Mammals he oldest component of the small mammal fauna is the TMonotremes. Marsupials are the most diverse of the terrestrial species. Our fauna had a southern origin and the first possum-like he most obvious mammals on the Station are the four species of ancestors entered Australia at least 45 million years ago while South T large kangaroos and so we have produced a separate guide for America, Antarctica and Australia were connected by land bridges. these. However, the diversity of mammals is much greater but most The placental mammals, bats and rodents, are more recent arrivals are rarely seen because they are small and exclusively night-active. from the north about 10 million years ago. Most of the genera are In the day the most likely small native mammal that you may see is found in New Guinea and Southeast Asia. The small mammal fauna the Echidna (or spiny ant-eater). This is a member of the of the Australian arid zone is unusual relative to other continents in monotremes, egg-laying mammals that millions of years ago were having a relatively low diversity of seed-eating rodents. This niche is quite diverse but became eclipsed by the marsupials and placentals. occupied by a much more diverse fauna of seed-eating ants than The monotremes are now only found here (the Echidna and elsewhere since the latter have a much older and longer association Platypus) and in New Guinea (two species of long-beaked Echidnas). -

Notes on the Diet of the Barn Owl Tyto Alba in New South Wales by A.B

VOL. 16 (8) DECEMBER 1996 327 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1996, 16 , 327-331 Notes on the Diet of the Barn Owl Tyto alba in New South Wales by A.B. ROSE, Associate, The Australian Museum, 6-8 College Street, Sydney, N.S.W. 2000 (present address: 61 Boundary Street, Forster, N.S.W. 2428) Summary The diet of the Barn Owl Tyto alba in New South Wales was examined by the analysis of pellets (2 sites, n = 9), pellet material (2 sites), and the stomach contents of owls found dead on roads (10 sites, n = 10) and away from roads (5 sites, n = 6). The introduced House Mouse Mus domesticus was by far the predominant prey item, although a small bat Vespadelus sp., native and introduced rats Rattus spp., dasyurid marsupials Planigale, Sminthopsis and Antechinus spp., a juvenile Cat Felis catus, birds and invertebrates were represented. The stomachs of owls found dead away from roads were empty; autopsies of those owls suggested poisoning by anticoagulant rodenticides. Introduction The diet of the Barn Owl Tyto alba is varied in Australia, with mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates having been recorded. However, rodents predominate, in particular the introduced House Mouse Mus domesticus (Schodde & Mason 1980 and references therein, Valente 1981, Baker-Gabb 1984, Smith & Cole 1989, Dickman et al. 1991, Hollands 1991, Johnson & Rose 1994). Most detailed dietary studies have been conducted in arid Australia or Victoria, with the few data for New South Wales comprising small samples analysed from the inland plains (Hermes & Stokes 1976) and the south coast (Smith 1984).