Notes on the Diet of the Barn Owl Tyto Alba in New South Wales by A.B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Pseudophyllinae from the Lesser Antilles (Orthoptera: Ensifera: Tettigoniidae)

Zootaxa 3741 (2): 279–288 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3741.2.6 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:156FF18E-0C3F-468C-A5BE-853CAA63C00F New Pseudophyllinae from the Lesser Antilles (Orthoptera: Ensifera: Tettigoniidae) SYLVAIN HUGEL1 & LAURE DESUTTER-GRANDCOLAS2 1INCI, UPR 3212 CNRS, Université de Strasbourg; 21, rue René Descartes; F-67084 Strasbourg Cedex. E-mail: [email protected] 2Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Département systématique et évolution, UMR 7205 CNRS, Case postale 50 (Entomologie), 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05, France. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Two new Cocconitini Brunner von Wattenwyl, 1895 species belonging to Nesonotus Beier, 1960 are described from the Lesser Antilles: Nesonotus caeruloglobus Hugel, n. sp. from Dominica, and Nesonotus vulneratus Hugel, n. sp. from Martinique. The songs of both species are described and elements of biology are given. The taxonomic status of species close to Nesonotus tricornis (Thunberg, 1815) is discussed. Key words: Orthoptera, Pseudophyllinae, Caribbean, Leeward Islands, Windward islands, Dominica, Martinique Résumé Deux nouvelles sauterelles Cocconotini Brunner von Wattenwyl, 1895 appartenant au genre Nesonotus Beier, 1960 sont décrites des Petites Antilles : Nesonotus caeruloglobus Hugel, n. sp. de Dominique, et Nesonotus vulneratus Hugel, n. sp. de Martinique. Le chant des deux espèces est décrit et des éléments de biologie sont donnés. Le statut taxonomique des espèces proches de Nesonotus tricornis (Thunberg, 1815) est discuté. Introduction Cocconotini species occur in most of the Lesser Antilles islands, including small and dry ones such as Terre de Haut in Les Saintes micro archipelago (S. -

Plaucident Planigale Version Has Been Prepared for Web Publication

#52 This Action Statement was first published in 1994 and remains current. This Plaucident Planigale version has been prepared for web publication. It Planigale gilesi retains the original text of the action statement, although contact information, the distribution map and the illustration may have been updated. © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2003 Published by the Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Plaucident Planigale (Planigale gilesi) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) 8 Nicholson Street, (Illustration by John Las Gourgues) East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia Description and Distribution these regions it is associated with habitats The Paucident Planigale (Planigale gilesi near permanent water or areas that are This publication may be of periodically flooded, such as bore drains, assistance to you but the Aitken 1972) is a small carnivorous creek floodplains or beside lakes (Denny State of Victoria and its marsupial. It was first described in 1972, employees do not guarantee and named in honour of the explorer Ernest 1982). that the publication is Giles who, like this planigale, was an In Victoria, it is found only in the north-west, without flaw of any kind or 'accomplished survivor in deserts' (Aitken adjacent to the Murray River downstream is wholly appropriate for 1972). from the Darling River (Figures 1 and 2). It your particular purposes It is distinguished by its flattened was first recorded here in 1985, extending its and therefore disclaims all triangular head, beady eyes and two known range 200 km further south from the liability for any error, loss most southern records in NSW (Lumsden et or other consequence which premolars on each upper and lower jaw al. -

Katydid (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) Bio-Ecology in Western Cape Vineyards

Katydid (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) bio-ecology in Western Cape vineyards by Marcé Doubell Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Agricultural Sciences at Stellenbosch University Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology, Faculty of AgriSciences Supervisor: Dr P. Addison Co-supervisors: Dr C. S. Bazelet and Prof J. S. Terblanche December 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Summary Many orthopterans are associated with large scale destruction of crops, rangeland and pastures. Plangia graminea (Serville) (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) is considered a minor sporadic pest in vineyards of the Western Cape Province, South Africa, and was the focus of this study. In the past few seasons (since 2012) P. graminea appeared to have caused a substantial amount of damage leading to great concern among the wine farmers of the Western Cape Province. Very little was known about the biology and ecology of this species, and no monitoring method was available for this pest. The overall aim of the present study was, therefore, to investigate the biology and ecology of P. graminea in vineyards of the Western Cape to contribute knowledge towards the formulation of a sustainable integrated pest management program, as well as to establish an appropriate monitoring system. -

Barn Owl (Tyto Alba) Predation on Small Mammals and Its Role in the Control of Hantavirus Natural Reservoirs in a Periurban Area in Southeastern Brazil Magrini, L

Barn owl (Tyto alba) predation on small mammals and its role in the control of hantavirus natural reservoirs in a periurban area in southeastern Brazil Magrini, L. and Facure, KG.* Laboratório de Taxonomia, Ecologia Comportamental e Sistemática de Anuros Neotropicais, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia – UFU, Rua Ceará, s/n, bloco 2d, sala 22b, CP 593, CEP 38400-902, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received September 25, 2006 – Accepted April 27, 2007 – Distributed November 30, 2008 (With 1 figure) Abstract The aim of this study was to inventory the species of small mammals in Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil, based on regurgitated pellets of the barn owl and to compare the frequency of rodent species in the diet and in the environment. Since in the region there is a high incidence of hantavirus infection, we also evaluate the importance of the barn owl in the control of rodents that transmit the hantavirus. Data on richness and relative abundance of rodents in the mu- nicipality were provided by the Centro de Controle de Zoonoses, from three half-yearly samplings with live traps. In total, 736 food items were found from the analysis of 214 pellets and fragments. Mammals corresponded to 86.0% of food items and were represented by one species of marsupial (Gracilinanus agilis) and seven species of rodents, with Calomys tener (70.9%) and Necromys lasiurus (6.7%) being the most frequent. The proportion of rodent species in barn owl pellets differed from that observed in trap samplings, with Calomys expulsus, C. tener and Oligoryzomys nigripes being consumed more frequently than expected. -

A Recent Report by the NSW Nature Conservation

BULLDOZING OF BUSHLAND NEARLY TRIPLES AROUND MOREE AND COLLARENEBRI AFTER SAFEGUARDS REPEALED IN NSW The Nature Conservation Council is a movement of passionate people who want nature in NSW to thrive. We represent more than 160 organisations and thousands of people who share this vision. Together, we are a powerful voice for nature. WWF has a long and proud history. We’ve been a leading voice for nature for more than half a century, working in 100 countries on six continents with the help of over five million supporters. WWF partners with governments, businesses, communities and individuals to address a range of pressing environmental issues. Our work is founded on science, our reach is international and our mission is exact – to create a world where people live and prosper in harmony with nature. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is acknowledged. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written consent. Citation: WWF-Australia and Nature Conservation Council of NSW (2018). In the spirit of respecting and strengthening partnerships with Australia’s First Peoples, we acknowledge the spiritual, social, cultural and economic importance of lands and waters to Aboriginal peoples. We offer our appreciation and respect for the First Peoples’ continued connection to and responsibility for land and water in this country, and pay our respects to First Nations Peoples and -

Population, Ecology and Morphology of Saga Pedo (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) at the Northern Limit of Its Distribution

Eur. J. Entomol. 104: 73–79, 2007 http://www.eje.cz/scripts/viewabstract.php?abstract=1200 ISSN 1210-5759 Population, ecology and morphology of Saga pedo (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) at the northern limit of its distribution ANTON KRIŠTÍN and PETER KAĕUCH Institute of Forest Ecology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Štúrova 2, 960 53 Zvolen, Slovakia; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Tettigoniidae, survival strategies, endangered species, large insect predators, ecological limits Abstract. The bush-cricket Saga pedo, one of the largest predatory insects, has a scattered distribution across 20 countries in Europe. At the northern boundary of its distribution, this species is most commonly found in Slovakia and Hungary. In Slovakia in 2003–2006, 36 known and potentially favourable localities were visited and at seven this species was recorded for the first time. This species has been found in Slovakia in xerothermic forest steppes and limestone grikes (98% of localities) and on slopes (10–45°) with south-westerly or westerly aspects (90%) at altitudes of 220–585 m a.s.l. (mean 433 m, n = 20 localities). Most individuals (66%) were found in grass-herb layers 10–30 cm high and almost 87% within 10 m of a forest edge (oak, beech and hornbeam being prevalent). The maximum density was 12 nymphs (3rd–5th instar) / 1000 m2 (July 4, 510 m a.s.l.). In a comparison of five present and previous S. pedo localities, 43 species of Orthoptera were found in the present and 37 in previous localities. The mean numbers and relative abundance of species in present S. -

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA updates. for Edition 4th Editors See A.C. Robinson K.D. Casperson Biological Survey and Research Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia M.N. Hutchinson South Australian Museum Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts, South Australia 2000 i EDITORS A.C. Robinson & K.D. Casperson, Biological Survey and Research, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage. G.P.O. Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001 M.N. Hutchinson, Curator of Reptiles and Amphibians South Australian Museum, Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts. GPO Box 234, Adelaide, SA 5001updates. for CARTOGRAPHY AND DESIGN Biological Survey & Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage Edition Department for Environment and Heritage 2000 4thISBN 0 7308 5890 1 First Edition (edited by H.J. Aslin) published 1985 Second Edition (edited by C.H.S. Watts) published 1990 Third Edition (edited bySee A.C. Robinson, M.N. Hutchinson, and K.D. Casperson) published 2000 Cover Photograph: Clockwise:- Western Pygmy Possum, Cercartetus concinnus (Photo A. Robinson), Smooth Knob-tailed Gecko, Nephrurus levis (Photo A. Robinson), Painted Frog, Neobatrachus pictus (Photo A. Robinson), Desert Goby, Chlamydogobius eremius (Photo N. Armstrong),Osprey, Pandion haliaetus (Photo A. Robinson) ii _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS -

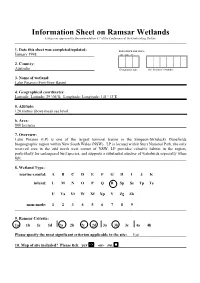

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. January 1998 DD MM YY 2. Country: Australia Designation date Site Reference Number 3. Name of wetland: Lake Pinaroo (Fort Grey Basin) 4. Geographical coordinates: Latitude: Latitude: 29º06’S; Longitude: Longitude: 141º13’E 5. Altitude: 120 metres above mean sea level. 6. Area: 800 hectares 7. Overview: Lake Pinaroo (LP) is one of the largest terminal basins in the Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields biogeographic region within New South Wales (NSW). LP is located within Sturt National Park, the only reserved area in the arid north west corner of NSW. LP provides valuable habitat in the region, particularly for endangered bird species, and supports a substantial number of waterbirds especially when full. 8. Wetland Type: marine-coastal: A B C D E F G H I J K inland: L M N O P Q R Sp Ss Tp Ts U Va Vt W Xf Xp Y Zg Zk man-made: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 9. Ramsar Criteria: 1a 1b 1c 1d 2a 2b 2c 2d 3a 3b 3c 4a 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: 1(a) 10. Map of site included? Please tick yes ⌧ -or- no. 11. Name and address of the compiler of this form: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Conservation Assessment and Planning Division PO BOX 1967 Hurstville NSW 2220 Phone: 02 9585 6477 AUSTRALIA Fax: 02 9585 6495 12. -

Winter Diet of the Barn Owl &Lpar;<I>Tyto Alba</I>&Rpar; and Long&Hyphen;Eared Owl &Lpar;<I>As

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS j. RaptorRes. 33(2):160-163 ¸ 1999 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. WINTER DtET OF THE B•'4 OWL (Trro AœBA)•'qD LONG-FA_•D OWL (As•o OTUS)IN NORTHEASTERN GREECE: A COMPARISON HARALAMBOS ALMZATOS 1 Zalihi 4, GR-11524Athens, Greece VASSILIS GOUTNER Departmentof Zoology,Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki,GR-54006 Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece K•¾ Worn)s: Barn Owl; Tyto alba; Long-earedOwl; Asio species,we calculatedevenness (E)(Ns, • = (N s - 1)/(N• otus; diet;,Greece. - 1), where N• = expH' and N s = 1/52p?)(Alatalo 1981, Marks 1984). In order to compare the dietary overlap There have been severalcomparative studies of the di- between speciesin each wetland, we used Pianka'sIndex (1973), multiplied by 100 to expressit as a percentage. ets of Barn (Tyt0 alba) and Long-eared (Asiootus) Owls (Marti 1974, Amat and Soriguer 1981, Mikkola 1983, De- RESULTS libes et al. 1983, Marks and Marti 1984, Cramp 1985, Capizzi and Luiselli 1996). Dietary information hasbeen The diets of both owls contained small mammals, useful in documentingthe trophic relationshipsin the birds, and insects,in descending order of importance areaswhere the two speciesare sympatric(Herrera and (Table 1). Smallmammals made up 92% of the Barn Owl Htraldo 1976, Marks and Marti 1984). Greece is within diet by number and 85% by biomass.At least 10 mammal the breeding and wintering areasof these species.Infor- specieswere eaten. The most important of them were mation on the diet of Barn Owl in Greece has come Mus spp. (40% by number and 32% by biomass),Microtus mainly from islands and parts of central and western epiroticus(20% and 28%), Apodemusspp. -

Bird Book 2020 for Website Ipages

BY ELIZABETH MONROE WITH JIM HYATT 2011 2011-20202014 The Birds of Capay Valley As featured in the Journals for The Greater Capay Va!ey Historical Society 20112011-2014-2020 RESEARCH, PHOTOGRAPHS AND WRITING BY ELIZABETH MONROE AND JIM HIATT -- 5th generation pioneer descendants of Capay Valley-Hungry Hollow 1- Cover The Birds of Capay Valley Table of Contents Taken from the Journals & Newsletters of The Greater Capay Valley Historical Society - 2011-2020 Below: Canada Geese on Cache Creek 2014 by Jim Hiatt I wish to thank Jim Hiatt for his wonderful support in my efforts to research and write about the greater Capay Valley from 2011 through 2020. In the course of doing this work, I discovered that Jim was a “hobby ornithologist” and asked him to contribute more pictures, information and personal stories or his 60-plus years watching the birds Page 1-2 = Black Birds of this area—and what a treasure I Page 3 = Blue & Scrub Jays was given! This book is a Page 4-6 = Blue Birds + Finch and Meadowlark compilation of all the articles Page 7 = Curlews to Cranes included in the series of Journals I Page 8-9 = Mallards created for The Greater Capay Valley Page 10 = Night Heron Historical Society and our many Page 11 = Magpie member-subscribers. Page 12 = Red-winged Black Bird Mostly, the articles are arranged in Page 13-15 = Mockingbird the order they were presented in the Page 16-17 = Meadowlark journals, which you can see in their Page 18-20 = Mourning Doves and Dove-weed complete form on our website at Pages 21-23 = Quail greatercapayvalley.org Pages 24-30 = Owls or by buying the book: The History Page 31 = Hawks and Stories of the Capay Valley, a Page 32 = Vultures compilation of all 18 journals; Page 33-35 = Western Kingbirds and Bullocks Orioles purchasing information is on the Page 36 = Poppies & Lupin website. -

Nantawarrina IPA Vegetation Chapter

Marqualpie Land System Biological Survey MAMMALS D. Armstrong1 Records Available Prior to the 2008 Survey Mammal data was available from four earlier traps (Elliots were not used during the first year), Department of Environment and Natural Resources compared to the two trap lines of six pitfalls and 15 (DENR) surveys which had some sampling effort Elliots, as is the standard for DENR surveys. within the Marqualpie Land System (MLS). These sources provided a total of 186 records of 16 mammal The three Stony Deserts Survey sites were located species (Table 18). These surveys were: peripheral to the MLS and in habitat that is unrepresentative of the dunefield, which dominates the • BS3 – Cooper Creek Environmental Association survey area. Therefore, only data collected at the 32 Survey (1983): 9 sites. Due to the extreme comparable effort survey sites sampled in 2008 is variability in sampling effort and difficulty in included in this section. All other data is treated as identifying site boundaries, this is simply the supplementary and discussed in later sections. number of locations for which mammal records were available. The 24 species recorded at sites consisted of five • BS41 – Della and Marqualpie Land Systems’ native rodents, five small dasyurids (carnivorous/ Fauna Monitoring Program (1989-92): 10 sites. insectivorous marsupials), five insectivorous bats, the • BS48 – Rare Rodents Project: one opportunistic Short-beaked Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), Red sighting record from 2000. Kangaroo (Macropus rufus) and Dingo (Canis lupus • BS69 – Stony Deserts Survey (1994-97): 3 sites. dingo), and six introduced or feral species. As is the case throughout much of Australia, particularly the An additional 20 records of seven mammal species arid zone, critical weight range (35g – 5.5kg) native were available from the SA Museum specimen mammal species, are now largely absent (Morton collection. -

Marsh Hawk Chases Crows Mobbing

March 1970 98 THE WILSON BULLETIN Vol. 82, No. 1 out of 246 attempts. All prey were captured on the ground. In 41 cases, the prey item was positively identified through binoculars or by the examination of fragments dropped in feeding. Of the identified items, 9 were short-horned grasshoppers (Acrididae), 19 were long-horned grasshoppers (Tettigoniidae), and 11 were lizards of the genus Anolis (probably Anolis limifrons). One item was a large cockroach (Blattidae) and the last was a small colubrid snake. This list is probably biased since grasshoppers and other large insects were difficult to identify at a distance but were abundant in the area. In about 30 cases where identity could not be certainly established, it appeared that the bird was tearing off wings as it characteristically did with large insects. The lizards and snake on the other hand, were easily distinguished by their long tails which hung down from the hawks’ talons. I recorded about thirty additional prey captures by other individuals wintering in the Turrialba area, but, because of the greater distance from the observer, only four of these could be identified. Two were Anolis lizards and one was a tettigoniid grasshopper. A good-sized Ameiva lizard (probably Ameiva festiva) was taken by a wintering female. Am&a lizards were present on the territory of the male hawk at the Institute, but no captures were recorded. It may be that the significantly larger size of females permits them to take larger prey, but these few data are not sufficient to justify such a state- ment.