Download PDF (543.5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Summary → International Markets

Week from 09/08/2014 to 09/12/2014 Market Summary 2 International Markets 2 Market and Sector News 3 At the international level France: 0.4% growth and 4.4% deficit for 2014 At the national level Automotive: Renault claimed 36.6% market share Cement: tentative signs of recovery ALLIANCES: Mr. Karim BELMAACHI resigns ... Former ADM boss recruited Attijariwafa bank: held in Cameroon for a loan of 150 billion BCP: Half Year Results 2014 CIH Bank: Half year results 2014 Label'Vie: will securitize its assets Lafarge Cement: Half year results 2014 Lesieur Cristal: Half Year Results 2014 Morocco Leasing: results up slightly Fundamental Data 5 Technical Data 67 5 6 1 3 Market Summary MARKET PERFORMANCE Performance Weekly evolution for Moroccan indexes vs. volume INDEXES Value Weekly 2014 500 104 MASI 9 830,89 1,98% 7,86% 450 103 MADEX 8 041,11 2,16% 8,40% 400 103 FTSE CSE 15 9 436,19 2,39% 6,95% 350 102 300 FTSE CSE All 8 439,04 2,00% 8,73% 102 250 Capi. (Billions of MAD) 483,95 -0,65% 7,28% 200 101 150 101 100 100 MARKET VOLUME OF THE WEEK 50 100 In Millions of MAD VOLUME % ADV* 0 99 Central Market 810,92 95,08% 162,18 9/8 9/9 9/10 9/11 9/12 OTC Market 41,98 4,92% 8,40 Global Market 852,90 100,0% 170,58 CM vol ume O TC vol ume M ASI M ADEX * Average Daily Volume A week in an upward trend for the Moroccan market. -

Property of Asempa Limited

S2106/455738 Administration www.africa-confidential.com 12 April 2013 - Vol 54 - N° 8 MALI/FRANCE BLUE LINES The campaign stretches out When Uhuru Kenyatta was sworn in as President of Kenya on 9 April, his supporters celebrated a double victory: his narrow win over Raila Odinga and the defeat of Western France commits to a long war just three months after launching its biggest detractors who predicted that his military operation in Africa in 50 years indictment by the International Criminal Court would undermine he official version is that France’s Mali Economic Community of West African States Kenya’s diplomatic position. The operation has achieved all its objectives playing the front-line role. France would reverse has been the case. T– the expulsion of jihadist forces from provide logistical and intelligence support Uganda’s President Yoweri main northern towns and the destruction and some European Union countries would Museveni led the charge at the of several bases in the Adrar des Ifoghas retrain the national army. inauguration: ‘I want to salute the mountains – apart from the rescue of seven Under the original plan, France was Kenyan voters...on the rejection of hostages still held in the region. This week not going to send combat troops. Hollande the blackmail by the International the withdrawal began, with 100 or so French had said categorically that there would be Criminal Court.’ Museveni, whose soldiers going home. France had airlifted no boots on the ground, although security own government is locked in 4,000 troops to Mali and sent another 2,000 experts suspected that French special forces battle with Western governments from its bases in Chad and Côte d’Ivoire. -

04931-9781452795188.Pdf

© 2007 International Monetary Fund January 2007 IMF Country Report No. 07/14 Niger: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix This Selected Issues paper and Statistical Appendix for Niger was prepared by a staff team of the International Monetary Fund as background documentation for the periodic consultation with the member country. It is based on the information available at the time it was completed on December 6, 2006. The views expressed in this document are those of the staff team and do not necessarily reflect the views of the government of Niger or the Executive Board of the IMF. The policy of publication of staff reports and other documents by the IMF allows for the deletion of market-sensitive information. To assist the IMF in evaluating the publication policy, reader comments are invited and may be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. Copies of this report are available to the public from International Monetary Fund Ɣ Publication Services 700 19th Street, N.W. Ɣ Washington, D.C. 20431 Telephone: (202) 623 7430 Ɣ Telefax: (202) 623 7201 E-mail: [email protected]Ɣ Internet: http://www.imf.org Price: $18.00 a copy International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution This page intentionally left blank ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND NIGER Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix Prepared by Mr. Sacerdoti (head-AFR), Mr. Farah, Mr. Fontaine, and Mr. Laporte (all AFR) Approved by African Department December 6, 2006 Contents Page I. Financial Sector Developments..............................................................................................4 A. Overview of the Financial Sector..............................................................................4 B. -

OED Case Study Cover For

To ward Country-led Development A Multi-Partner Evaluation of the Comprehensive Development Framework Findings from Six Country Case Studies BOLIVIA BURKINA FASO GHANA ROMANIA UGANDA VIETNAM © 2003 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www.worldbank.org E-mail [email protected] All rights reserved. 1 2 3 4 05 04 03 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations or institutions they represent, or of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denom- inations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permis- sion may be a violation of applicable law. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

Ranking 2O18

RANKING 2O18 AFRICA Economic Leaders for Tomorrow PARTNERS 2 Pascal Lorot Chairman, Institut Choiseul frica is inserting itself more than and accomplishment. These entrepreneurs Aever in global economic circuits perfectly know the practices and the where it is imposing as a central actor. expectations of an international business After a year of slowing growth in 2016, world in which they integrate with Africa is demonstrating its great resilience brilliance. capacity. According to the African Bank The purpose ofChoiseul 100 Africa – of Development, the GDP growth has the Economic Leaders for Tomorrow is increased in 2017 to reach 3.6%, and to honor those exceptional profiles who will exceed 4% in 2018 and 2019 thanks contribute to the renewing of the African to several factors: the staging of great economic governance. For this fifth infrastructures projects, the growth of edition, the Institut Choiseul called on a sustained domestic demand as well as the best observers of the continent, along the improvement of the international with local actors who make the African economic context. economic actuality. The objective of this Nevertheless, Africa is still facing structural process is to identify the entrepreneurs impediments which stem its development : who will make tomorrow’s Africa and who the lack of infrastructures and equipment, will carry its growth. the dependency on raw materials of many We are proud to introduce in this ranking continental economies among the most the best representatives of this new wave important ones which expose Africa to of successful leaders and entrepreneurs exogenous shocks, the insufficiency of who already are references nationally, human capital… Many characteristics regionally or continentally. -

World Bank Document

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: PIDA64910 Public Disclosure Authorized Project Name Mali Support to Agroindustrial Competitiveness Project (P151449) Region AFRICA Country Mali Public Disclosure Copy Lending Instrument Investment Project Financing Project ID P151449 Borrower(s) Ministry of Economy and Finance Implementing Agency Ministry of Agriculture Environmental Category B-Partial Assessment Date PID Prepared/Updated 30-Sep-2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Date PID Approved/Disclosed 30-Sep-2016 Estimated Date of Appraisal 22-Nov-2016 Completion Estimated Date of Board 22-Nov-2016 Approval Appraisal Review Decision The review did authorize the team to appraise and negotiate (from Decision Note) I. Project Context Country Context Mali is one of the world poorest countries with a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of US Public Disclosure Authorized $704.50 in 2014. Life expectancy is low (57 years of age); malnutrition levels are high (28 percent of under-five children are stunted); and most of the 17.1 million population is illiterate (69 percent of adults). The economy of this landlocked country is predominantly rural and informal: 64 percent of the population resides in rural areas, and 80 percent of the jobs are in the informal sector. Public Disclosure Copy The incidence of poverty is high and predominantly rural. Before the 2012 political and security crisis, Mali had succeeded in reducing poverty, mainly because of increased agricultural production and better functioning value chains. Between 2000 and 2010, the incidence of poverty declined from 60 percent to 51 percent. In 2010, half the population lived below the US$1.9/day poverty line and 90 percent of the poor live in rural areas. -

Kagame « L’Afrique N’A Pas Besoin De Baby-Sitters » Une Interview Exclusive Du Président Du Rwanda Et De L’Union Africaine

GUINÉE 2019 A DOING BUSINESS IN AFRIC TCHAD TUNISIE exploité GUIDE enfin) l( . ,logement, aménagementplan de développement, urbain… ommerce de son économie ture,c mbitieux clés râce àuna cteurs mplois. Un potentie ce,g les se sete son indépendan énérant ressource Hafedh Caïd Essebsi, Infrastructures, mines, agriculsupérieure dansteng tous INVESTIR avitesse Soixante anspass aprèseàl Nouvelle République Guinée la De quoi rassurer les investisseurs, tou Spécial 14 pages le pouvoir en héritage ? EN GUINÉE HEBDOMADAIRE INTERNATIONAL NO 2996 DU 10 AU 16 JUIN 2018 19 20 GUINÉE RD Congo Francophonie Burundi Macron Trump Réforme de l’UA Migrants Mandats présidentiels Droits de l’homme… Kagame « L’Afrique n’a pas besoin de baby-sitters » Une interview exclusive du président du Rwanda et de l’Union africaine ÉDITION INTERNATIONALE ET AFRIQUE SUBSAHARIENNE France 3,80 €.Algérie 290 DA.Allemagne 4,80 €.Autriche 4,80 €.Belgique 3,80 €.Canada 6,50 $ CAN.Espagne 4,30 €.Éthiopie 67 birrs.Grèce 4,80 € Guadeloupe 4,60 €.Guyane 5,80 €.Italie 4,30 €.Luxembourg 4,80 €.Maroc 25 DH.Martinique 4,60 €.Mayotte 4,60 €.Norvège 48 NK.Pays-Bas 4,80 € Portugal cont. 4,30 €.Réunion 4,60 €.RD Congo 6,10 $ US.Royaume-Uni 3,60 £.Suisse 7 FS.Tunisie 3,50 DT.USA 6,90 $ US.Zone CFA 2 000 F CFA.ISSN 1950-1285 ❴❵❛❜❢✐ ❴❥❦ ❧q❜✈❥✇ ①①②③④⑤⑥⑦⑤⑧⑨⑩❶❷⑥⑤❸❹❺❻ ■◗❘❲❳❨ ❩ ❬❭❨❪ ❡ ✁ ➠ ✂ ♦ ✄ ✄ ❡ ☎ ✂ s ✂ ❡ ✄ ✟ ✂ ✂ ✟ ✡ ❡ ✂ ♣ ♦ r ✡ ❡ ✂ ♣ ♦ r ☎ ❡ r☛ ❆ ✡ ♦ r ✂ ✞❡ ♣♦ ✒♠✟ ❡✞☎ ✟❣✞♦r❡r✱ ♦ ✞☎ ✎ ☎♠✠✡✟ ✂ ✆ ✆ ✝ ❞ ❡ ✞ ☎ ✄ ♠ ✟ ✂ ✞ ❡ ✙ ❡ ✡☞❖✆✆✟❞❡✞☎ ❡✂☎ ❡✞ r❡✆ ✡ ❡☎ ✙ ❡ ♦ ✞ ✡ ❡ ✂ ✠ ✄ ❡r ❣ ❡r♠ ❞☞♠✄♠✠ ✟ ✡✟ ☎✎✂ ✱ -

Download the Abidjan-Ouagadougou Factsheet

Context The Trade Facilitation West Africa (TFWA) Program is an initiative supported by multiple development partners (EU, Netherlands, USAID, and Germany) to improve trade facilitation in West Africa. The program focuses its activities along six major trade corridors in the region: • Abidjan – Ouagadougou • Lomé – Ouagadougou • Tema – Ouagadougou • Cotonou – Niamey • Dakar – Bamako • Lagos – Kano – Niamey The TFWA Program’s main objective is to reduce the time and cost of trade along these priortiy corridors. On the Abidjan - Ouagadougou corridor, the program aims to: Improve and implement more ecient trade facilitation measures while strengthening private sector commitment Improve bilateral border agency operations and coordination Improve the movement of goods along these key corridors while promoting containerized trade Improve economic empowerment for small traders and other key stakeholders, in particular women, by implementing trade facilitation reforms that reduce barriers to trade Key information on the Abidjan - Ouagadougou Corridor • The total length of the corridor is about 1,263 kms, of which approximately 653 kms are in Côte d'Ivoire. • A metric gauge railway line approximately 1,238 kms long serves the Abidjan-Ouagadougou corridor. The average split between road and rail transport is approximately 75% for road and 25% for rail. • There are approximately 20 checkpoints (police, customs, gendarmerie and others) along the Abidjan - Ouagadougou corridor. The control times per body are: 18 for police, 1 for customs, 15 for gendarmerie, and 3 for others. • Looking at the time it take to cross borders, import procedures are heavier in Côte d'Ivoire than in Guinea Bissau and Senegal. Nine export documents are required, 25 days of export time are required, and the export cost per container is 1,390 USD (the same as the deflated export cost per container). -

Burkina Faso's Infrastructure: a Continental Perspective

COUNTRY REPORT Burkina Faso’s Infrastructure: A Continental Perspective Cecilia Briceño-Garmendia and Carolina Domínguez-Torres MAY 2011 © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved A publication of the World Bank. The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

The Ouagadougou Partnership's Advances in Family Planning

An Improbable Success: The Ouagadougou Partnership’s Advances in Family Planning Across Francophone West Africa By Janet Fleischman 1 Ouagadougou Partnership Retrospective Report About the author Janet Fleischman, an independent consultant on women’s global health, was commissioned in 2019 by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to write this report documenting the history of the Ouagadougou Partnership. She completed her research in January 2020, before the first cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in Francophone West Africa (in Senegal and Burkina Faso) in March 2020. Accordingly, this report does not address the impact of COVID-19 in Francophone West Africa or the challenges it presents to the Ouagadougou Partnership’s activities. An abridged version of this report was authored by Janet Fleischman and Marie Ba, the director of the Ouagadougou Partnership Coordinating Unit (OPCU), and published in Think Global Health on March 18, 2020, www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/improbable-success- troubled-region. Cover image: Contraceptive methods user couple in Dangbo, Benin. Photo by Yves-Constant Tamomo for EtriLabs. Contents Regional Background and Inspiration for the Ouagadougou Partnership 6 Genesis of a Regional Partnership 9 Launch of the Ouagadougou Partnership 12 New Tools – Development of Costed Implementation Plans (CIPs) 14 Creating a Structure – The OPCU 15 Implementing the Vision 17 Next Phase: Acceleration 29 Progress Toward Regional and Global Impact 30 Challenges 32 The Way Forward 36 An Improbable Success: The Ouagadougou Partnership’s Advances in Family Planning Across Francophone West Africa Sometimes innovation to spur social change arises in unexpected places. In 2011, in Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, representatives from nine Francophone West African countries joined with international donors to launch a simple but radical plan. -

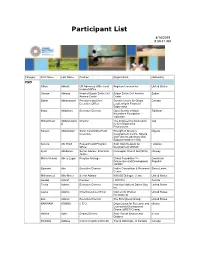

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Executive Summary

Executive Summary There has been a rapid expansion of pan-African banks (PABs) in recent years, with seven major PABs having a presence in at least ten African countries: three of these are headquartered in Morocco, two in Togo, and one each in Nigeria and South Africa. Additional banks, primarily from Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa, have a regional presence with operations in at least five countries. PABs have a systemic presence in around 36 countries. Overall, the PABs are now much more important in Africa than the long-established European and American banks. PABs have expanded mainly through subsidiaries, via the acquisition of existing banks. Only a few PABs have used greenfield investments to expand across countries. Subsidiarization reflects regulators’ wish to minimize contagion, particularly given the relatively high risks associated with banking activity in the continent. The growth of PABs offers a number of opportunities and benefits. The expansion of these banks reflects the increase in economic integration within Africa more generally and is contributing to improve competition, support financial inclusion, and give rise to greater economies of scale. In addition, PABs have been filling the recent gap left by European banks and are becoming the lead arrangers of syndicated loans (IMF 2014b). At the same time, the rapid expansion of PABs poses oversight challenges that if unaddressed, may increase systemic risks. Supervisory capacity is already constrained and under-resourced in most of Africa. PABs raise the importance of transparency and disclosure, good governance, strong prudential oversight, and a legal and regulatory framework that supports effective and comprehensive supervision and crisis management, particularly in the countries that are homes to major PABs.