REGIONAL OFF-GRID ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Off

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Summary → International Markets

Week from 09/08/2014 to 09/12/2014 Market Summary 2 International Markets 2 Market and Sector News 3 At the international level France: 0.4% growth and 4.4% deficit for 2014 At the national level Automotive: Renault claimed 36.6% market share Cement: tentative signs of recovery ALLIANCES: Mr. Karim BELMAACHI resigns ... Former ADM boss recruited Attijariwafa bank: held in Cameroon for a loan of 150 billion BCP: Half Year Results 2014 CIH Bank: Half year results 2014 Label'Vie: will securitize its assets Lafarge Cement: Half year results 2014 Lesieur Cristal: Half Year Results 2014 Morocco Leasing: results up slightly Fundamental Data 5 Technical Data 67 5 6 1 3 Market Summary MARKET PERFORMANCE Performance Weekly evolution for Moroccan indexes vs. volume INDEXES Value Weekly 2014 500 104 MASI 9 830,89 1,98% 7,86% 450 103 MADEX 8 041,11 2,16% 8,40% 400 103 FTSE CSE 15 9 436,19 2,39% 6,95% 350 102 300 FTSE CSE All 8 439,04 2,00% 8,73% 102 250 Capi. (Billions of MAD) 483,95 -0,65% 7,28% 200 101 150 101 100 100 MARKET VOLUME OF THE WEEK 50 100 In Millions of MAD VOLUME % ADV* 0 99 Central Market 810,92 95,08% 162,18 9/8 9/9 9/10 9/11 9/12 OTC Market 41,98 4,92% 8,40 Global Market 852,90 100,0% 170,58 CM vol ume O TC vol ume M ASI M ADEX * Average Daily Volume A week in an upward trend for the Moroccan market. -

F:\Niger En Chiffres 2014 Draft

Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 1 Novembre 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Direction Générale de l’Institut National de la Statistique 182, Rue de la Sirba, BP 13416, Niamey – Niger, Tél. : +227 20 72 35 60 Fax : +227 20 72 21 74, NIF : 9617/R, http://www.ins.ne, e-mail : [email protected] 2 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Pays : Niger Capitale : Niamey Date de proclamation - de la République 18 décembre 1958 - de l’Indépendance 3 août 1960 Population* (en 2013) : 17.807.117 d’habitants Superficie : 1 267 000 km² Monnaie : Francs CFA (1 euro = 655,957 FCFA) Religion : 99% Musulmans, 1% Autres * Estimations à partir des données définitives du RGP/H 2012 3 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 4 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Ce document est l’une des publications annuelles de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Il a été préparé par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Service de la Coordination Statistique. Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’INS : les structures : - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Economiques (DSEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Ibrahim SOUMAILA, Secrétaire Général P.I de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les membres du Comité de Lecture de l’INS. Il s’agit de : - Adamou BOUZOU, Président du comité de lecture de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Djibo SAIDOU, membre du comité - Mahamadou CHEKARAOU, membre du comité - Tassiou ALMADJIR, membre du comité - Halissa HASSAN DAN AZOUMI, membre du comité - Issiak Balarabé MAHAMAN, membre du comité - Ibrahim ISSOUFOU ALI KIAFFI, membre du comité - Abdou MAINA, membre du comité. -

Arrêt N° 012/11/CCT/ME Du 1Er Avril 2011 LE CONSEIL

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 012/11/CCT/ME du 1er Avril 2011 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du premier avril deux mil onze tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la Constitution ; Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-096 du 28 décembre 2010 portant code électoral ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2011-121/PCSRD/MISD/AR du 23 février 2011 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le deuxième tour de l’élection présidentielle ; Vu l’arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2011 ; Vu l’arrêt n° 006/11/CCT/ME du 22 février 2011 portant validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 31 janvier 2011 ; Vu la lettre n° 557/P/CENI du 17 mars 2011 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 2ème tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 028/PCCT du 17 mars 2011 de Madame le Président du Conseil constitutionnel portant -

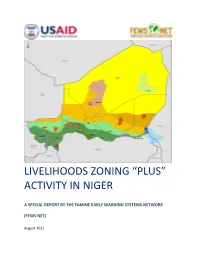

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

A Mixed Methods Study on the Influence of a Seasonal Cash Transfer and Male Labour Migration on Child Nutrition in Tahoua, Niger

A mixed methods study on the influence of a seasonal cash transfer and male labour migration on child nutrition in Tahoua, Niger Victoria Louise Sibson Institute for Global Health Thesis submitted for degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London 2014-2019 2 Declaration I, Victoria Sibson, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed…………………………………… Date……………………………………… 3 4 Abstract Unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) are used to prevent acute malnutrition in emergencies but evidence on their effectiveness is lacking. In Niger, NGOs implemented annual UCTs with supplementary feeding during the June–September lean season, despite feeding programme admissions sometimes rising earlier. I hypothesised that starting the UCT earlier would reduce acute malnutrition prevalence in children 6-59 months old, but also, that this would promote early return of seasonal male labour migrants (exodants), limiting the effectiveness of the modified UCT. A cluster-randomised trial involved the poorest households receiving either the standard monthly UCT (June-September) or a modified UCT (April-September); both providing a total of 130,000 FCFA/£144. Pregnant and lactating women and children 6–<24 months old in beneficiary households also received supplementary food (June-September). We collected quantitative data from a cohort of households and children in March/April and October/November 2015 and conducted a process evaluation. The modified UCT did not reduce acute malnutrition prevalence compared with the standard UCT. Among beneficiaries in both arms the prevalence of GAM remained elevated at endline (14.7, 95%CI 12.9, 16.9), despite improved food security, possibly due to increased fever/reported malaria. -

Burkina Faso Mali Niger Nigeria Bénin

APERÇU DU CONTEXTE: FRONTIERE NIGER - MALI - BURKINA FASO De janvier à juin 2019 Kidal " Kal Talabit " "Chibil Ifourgoumissen "Tin Tersi "Ibibityene Win-ihagarane " Irayakane Ahel Baba Ould Cheick " Takalot " " "Imakalkalane 1 Ifarkassane"Ifarkassane Inheran " " " Imrad Araghnen Kal Taghlit " Idabagatane Mali Taghat Malat "" Kal Essouk " "" Kal Edjerer Niger "Ahel Bayes "" Ahel Acheicl Sidamar"" " Anefif "" "Kannay Ahel Sidi Alamine Anefif " "Kel Ten"ere 2 Kal Affala Ibohanane Inharane Kal Tidjareren " Kal Ouzeine 3 Kel Teneré2 " " Oulad Sidi El Moctar " Oulad El Waffi "Oulad Ben Amar "Ifacar Gouanines Noirs Guiljiat " " Burkina " Arouagene Idaourack " "Idnane Nadag Kel Agueris Temakest " Inherene " " Faso Ahel Abidine Baba Ahmed Ibilbitienne Winadous " " Tenikert Oulad Driss Berabich Tagirguirt Kaolet " " " " Ahel Cheick Sidi Al Bekaye " In Tebezas "Ahel Bady Ahel Sidi Haiballa Ahel Sidi B"aba Amed " " Igdalane Dag Mohamed Aly Kel Tenere 1 "Ahel Sidi Cheick " " "Amassine Agouni " " Agadez Ahel-chegui "Achibogho "Kel Dihnane Oulad Malloreck Kel Dihane " "Ahel Abdallah Ibrahim Dabacar "Tinafewa " Kel Emnanou Cherifene Arbakoira " " Tarkint Cheriffene Abakoira " Imagrane Kel Amassine " Kel Inablahane " " Icharamatane Idnane "Ahel Lawal Ichamaratene " " "Kel Tagho "Kel Takaraghate " Kel Taborack Kel Inseye Kel Takaraghate Kalawate Oulad Souleymane Oulad Ganam " "Ahel Bokel " " Icherifen " Ahel Sidi Moussa " Iguerossouane Kel Sidalamine Foulane " Tafez Fez Oulad Boxib " " " " Ahel Sidi Cedeg Tagalift Houassa " Tagalift Gourma " "Amagor Amakal -

Stratégie De Développement Rural

République du Niger Comité Interministériel de Pilotage de la Stratégie de Développement Rural Secrétariat Exécutif de la SDR Stratégie de Développement Rural ETUDE POUR LA MISE EN PLACE D’UN DISPOSITIF INTEGRE D’APPUI CONSEIL POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL AU NIGER VOLET DIAGNOSTIC DU RÔLE DES ORGANISATIONS PAYSANNES (OP) DANS LE DISPOSITIF ACTUEL D’APPUI CONSEIL Rapport provisoire Juillet 2008 Bureau Nigérien d’Etudes et de Conseil (BUNEC - S.A.R.L.) SOCIÉTÉ À RESPONSABILITÉ LIMITÉE AU CAPITAL DE 10.600.000 FCFA 970, Boulevard Mali Béro-km-2 - BP 13.249 Niamey – NIGER Tél : +227733821 Email : [email protected] Site Internet : www.bunec.com 1 AVERTISSEMENTS A moins que le contexte ne requière une interprétation différente, les termes ci-dessous utilisés dans le rapport ont les significations suivantes : Organisation Rurale (OR) : Toutes les structures organisées en milieu rural si elles sont constituées essentiellement des populations rurales Organisation Paysanne ou Organisation des Producteurs (OP) : Toutes les organisations rurales à caractère associatif jouissant de la personnalité morale (coopératives, groupements, associations ainsi que leurs structures de représentation). Organisation ou structure faîtière: Tout regroupement des OP notamment les Union Fédération, Confédération, associations, réseaux et cadre de concertation. Union : Regroupement d’au moins 2 OP de base, c’est le 1er niveau de structuration des OP. Fédération : C’est un 2ème niveau de structuration des OP qui regroupe très souvent les Unions. Confédération : Regroupement les fédérations des Unions, c’est le 3ème niveau de structuration des OP Membre des OP : Personnes physiques ou morales adhérents à une OP Adhérents : Personnes physiques membres des OP Promoteurs ou structures d’appui ou partenaires : ce sont les services de l’Etat, ONG, Projet ou autres institutions qui apportent des appuis conseil, technique ou financier aux OP. -

Région De Agadez Pour Usage Humanitaire Uniquement CARTE DE REFERENCE Date De Production : 21 Mars 2018

Niger - Région de Agadez Pour Usage Humanitaire Uniquement CARTE DE REFERENCE Date de production : 21 mars 2018 6°0'0"E 9°0'0"E 12°0'0"E 15°0'0"E Libye Madama " N " 0 ' 0 ° 2 Tchad 2 Djado Inazawa " "Yaba "Tchounouk " Djado ""Tchibarkatene Tchibarkatene " Chirfa Algérie "Sara "Touaret Dan Timni Iferouane " Tchingalene " Tchingalene Tamjit Iferouane " " Tamjit "Amji Temet Taghajit " " Bilma "Siguidine "Intikikitene N " 0 Ourarene Ii " ' 0 " ° 0 Ourarene I 2 "Assamaka Ezazaw Gougaram " Farzakat Tchirawayen " " Dirkou Azatraya Abarkot " Mama Manat " Arlit " "Korira "Tezirzait Tadek Est Tadek Ouest " " "Ifiniyan Tchin Dagar"a " Tch" inkawkane " Etaghass " " " Anouzaghaghane Arso " Taghwaye Tchiwalmass Et Agreroum Agharouss " " Oumaratt " " " " " " " Izayakan Tadekilt " "Aneye Elaglag Ii " Lateye Amizigra " " " " Iferouane Agly Eknawan Emitchouma " " Fares Tchouwoye " " Tagze " "" " " Issawan Tamat " " " Ebidni Tchifirissene " Souloufiet " Awey Kisse " " "Aboughalel Tamgak Tanout-Mollat " Infara " " " Arlit Ezil " Ebourkoum Temedrissou " Ichifa Tadaous " " " Achinouma Gabo Anouzagagan " "Ingall " Wizat " " " " " " " Maghet " Anigaran " "Elabag Zanawey " Temelait Argui Boukoki Ii (Est) " " "" Inwourigan Arakam """ " Carre Nouveau Marche " " " " " " Tamazan I " " " " "" Iko " Barara "" Ziguilaw " Taghait Kerdema Akokan Carre C " Tiliya " Eghighi " " Tirgaf " Eggar " " " " Tagmert " " Tassilim Agorass N'Imi" Iguintar Azangneriss " " " Arag 1 Tarainat " " Agalal " " Agheytom " Chimaindour " " " Madawela Madawela " Wiye " " " " Tamilik Mayat 2 -

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique Au Niger»

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique au Niger» DIFEB, le 16 Août 2019 SOMMAIRE CEV Plan de déploiement Détails Zone 1 Détails Zone 2 Avantages/Limites CEV Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote CEV: Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote Notion apparue avec l’introduction de la Biométrie dans le système électoral nigérien. ▪ Avec l’utilisation de matériels sensible (fragile et lourd), difficile de faire de maison en maison pour un recensement, C’est l’emplacement physique où se rendront les populations pour leur inscription sur la Liste Electorale Biométrique (LEB) dans une localité donnée. Pour ne pas désorienter les gens, le CEV servira aussi de lieu de vote pour les élections à venir. Ainsi, le CEV contiendra un ou plusieurs bureaux de vote selon le nombre de personnes enrôlées dans le centre et conformément aux dispositions de création de bureaux de vote (Art 79 code électoral) COLLECTE DES INFORMATIONS SUR LES CEV Création d’une fiche d’identification de CEV; Formation des acteurs locaux (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil) pour le remplissage de la fiche; Remplissage des fiches dans les communes (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil et 3 personnes ressources); Centralisation et traitement des fiches par commune; Validation des CEV avec les acteurs locaux (Traitement des erreurs sur place) Liste définitive par commune NOMBRE DE CEV PAR REGION Région Nombre de CEV AGADEZ 765 TAHOUA 3372 DOSSO 2398 TILLABERY 3742 18 400 DIFFA 912 MARADI 3241 ZINDER 3788 NIAMEY 182 ETRANGER 247 TOTAL 18 647 Plan de Déploiement Plan de Déploiement couvrir tous les 18 647 CEV : Sur une superficie de 1 267 000 km2 Avec une population électorale attendue de 9 751 462 Et 3 500 kits (3000 kits fixes et 500 tablettes) ❖ KIT = Valise d’enrôlement constitués de plusieurs composants (PC ou Tablette, lecteur d’empreintes digitales, appareil photo, capteur de signature, scanner, etc…) Le pays est divisé en 2 zones d’intervention (4 régions chacune) et chaque région en 5 aires. -

Property of Asempa Limited

S2106/455738 Administration www.africa-confidential.com 12 April 2013 - Vol 54 - N° 8 MALI/FRANCE BLUE LINES The campaign stretches out When Uhuru Kenyatta was sworn in as President of Kenya on 9 April, his supporters celebrated a double victory: his narrow win over Raila Odinga and the defeat of Western France commits to a long war just three months after launching its biggest detractors who predicted that his military operation in Africa in 50 years indictment by the International Criminal Court would undermine he official version is that France’s Mali Economic Community of West African States Kenya’s diplomatic position. The operation has achieved all its objectives playing the front-line role. France would reverse has been the case. T– the expulsion of jihadist forces from provide logistical and intelligence support Uganda’s President Yoweri main northern towns and the destruction and some European Union countries would Museveni led the charge at the of several bases in the Adrar des Ifoghas retrain the national army. inauguration: ‘I want to salute the mountains – apart from the rescue of seven Under the original plan, France was Kenyan voters...on the rejection of hostages still held in the region. This week not going to send combat troops. Hollande the blackmail by the International the withdrawal began, with 100 or so French had said categorically that there would be Criminal Court.’ Museveni, whose soldiers going home. France had airlifted no boots on the ground, although security own government is locked in 4,000 troops to Mali and sent another 2,000 experts suspected that French special forces battle with Western governments from its bases in Chad and Côte d’Ivoire. -

Cadre De Gestion Environnementale Et Sociale (Cges) (Precis, Prodaf

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité-Travail-Progrès MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE ET DE L’ELEVAGE Cellule Nationale de Représentation et d’Assistance Technique (CENRAT) CADRE DE GESTION ENVIRONNEMENTALE ET SOCIALE (CGES) (PRECIS, PRODAF, PRODAF DIFFA) Rapport définitif August 2020 TABLE DES MATIERES Liste des sigles et abréviation ................................................................................................................................ iv Liste des cartes ...................................................................................................................................................... vii Liste des tableaux .................................................................................................................................................. vii Liste des figures ................................................................................................................................................... viii RESUME NON TECHNIQUE ............................................................................................................................... 1 Mécanisme de gestion des plaintes ................................................................................................................... 11 Les différentes types de plaintes ....................................................................................................................... 12 Recueil, traitement et résolution des réclamations ........................................................................................... -

04931-9781452795188.Pdf

© 2007 International Monetary Fund January 2007 IMF Country Report No. 07/14 Niger: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix This Selected Issues paper and Statistical Appendix for Niger was prepared by a staff team of the International Monetary Fund as background documentation for the periodic consultation with the member country. It is based on the information available at the time it was completed on December 6, 2006. The views expressed in this document are those of the staff team and do not necessarily reflect the views of the government of Niger or the Executive Board of the IMF. The policy of publication of staff reports and other documents by the IMF allows for the deletion of market-sensitive information. To assist the IMF in evaluating the publication policy, reader comments are invited and may be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. Copies of this report are available to the public from International Monetary Fund Ɣ Publication Services 700 19th Street, N.W. Ɣ Washington, D.C. 20431 Telephone: (202) 623 7430 Ɣ Telefax: (202) 623 7201 E-mail: [email protected]Ɣ Internet: http://www.imf.org Price: $18.00 a copy International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution This page intentionally left blank ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND NIGER Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix Prepared by Mr. Sacerdoti (head-AFR), Mr. Farah, Mr. Fontaine, and Mr. Laporte (all AFR) Approved by African Department December 6, 2006 Contents Page I. Financial Sector Developments..............................................................................................4 A. Overview of the Financial Sector..............................................................................4 B.