Report to the Congress on the Compacts of Free Association With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey Report on the Present State of Nan Madol, Federated States of Micronesia

2010 Survey for International Cooperation Japan Consortium for International Cooperarion in Cultual Heritage Survey Report on the Present State of Nan Madol, Federated States of Micronesia March 2012 Japan Consortium for International Cooperation in Cultual Heritage Foreword 1. This is a report on the fiscal 2010 survey conducted by the Japan Consortium for International Cooperation in Cul- tural Heritage in regard to the archaeological site of Nan Madol in the Federated States of Micronesia. 2. The following members were responsible for writing each of the chapters of this report. Writers: Chapters 1, 4, 6 – Tomomi Haramoto Chapters 2, 3 – Osamu Kataoka Chapter 5 – Tomo Ishimura Editor: Tomomi Haramoto, Japan Consortium for International Cooperation in Cultural Heritage i ii Preface The Japan Consortium for International Cooperation in Cultural Heritage (JCIC-Heritage) collects information in various forms to promote Japan’s international cooperation on cultural heritage. Under this scheme of information collection, a cooperation partner country survey was conducted in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in fiscal 2010, as presented in this report. It was conducted in response to a request from the UNESCO Apia Office, to provide a foundation of information that would facilitate the first steps toward protecting Nan Madol, the largest cultural heritage site in FSM. Cooperation partner country surveys are one of the primary activities of JCIC-Heritage’s initiatives for interna- tional cooperation. They particularly focus on collecting basic information to identify fields of cooperation and their feasibility in a relevant partner country. As of fiscal 2011, cooperation surveys have been conducted in Laos, Mongo- lia, Yemen, Bhutan, Armenia, Bahrain, and Myanmar, and have effectively assisted Japan’s role in international coop- eration. -

COMET Spring 2015 Statistical Exploration by High School

COMET Spring 2015 Statistical Exploration by High School This document is an exploration of data from the College of Micronesia-FSM spring 2015 entrance COMET with a focus on individual high school and section statistics. In this document the word "sections" refers to high school sections. The word subsection will be used to refer to the different sections of the COMET entrance instrument. This document should be construed as an occasional informal paper by a member of faculty. Any opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect an official position of the college. Basic Statistics for All Candidates The COMET consists of four subsections: a written essay, a vocabulary test, a comprehension test, and a mathematics placement test. Total possible for the essay is 50 points. The mathematics subsection has four sets of ten problems designed to help place students. The total possible for the sum of the mathematics scores is 40. Nelson-Denny is used for the vocabulary and comprehension sections. Statistic Essay Vocabulary Reading MS1 MS2 MS3 MS4 Math sum n 1455 1456 1456 1456 1456 1456 1456 1456 min 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 max 50 69 38 10 10 10 10 38 mode 30 22 15 8 6 2 2 18 median 30 23 16.5 7 6 3 3 19 mean 28.28 24.78 17.28 6.94 6.01 3.59 2.90 19.44 sx 12.80 10.18 6.37 2.28 2.20 2.32 1.87 6.88 cv 0.45 0.41 0.37 0.33 0.37 0.65 0.65 0.35 High School Listing The following is a list of the high school names used in tables in this report. -

The Status of the Endemic Snails of the Genus Partula (Gastropoda: Partulidae) on Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia

Micronesica 41(2):253–262, 2011 The status of the endemic snails of the genus Partula (Gastropoda: Partulidae) on Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia. Peltin Olter Pelep and Michael G. Hadfield Kewalo Marine Laboratory Pacific Biosciences Research Center; University of Hawaii at Manoa 41 Ahui Street; Honolulu, Hawaii 96813, USA Abstract—Approximately 21 terrestrial snail species are endemic to Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). The only extensive sur- veys for terrestrial snails on the island were carried out by Y. Kondo in 1936. Subsequently, forests have been destroyed and non-native preda- tors have taken their toll on the gastropod fauna, and its current status is unknown. The present study focused on Partula guamensis and P. emersoni, two of approximately 120 species in the family Partulidae dis- persed across the tropical Pacific Islands. Over 40 different localities on Pohnpei were extensively searched between August 2005 and May 2006 and between May and July 2008 to assess the status of the two Partula species. The habitats searched were mixed agro-forest, disturbed forest, rain forest and cloud forest, ranging from sea level to the highest peaks and ridges on the island. No living partulid snails were found, and the only shells collected, those of Partula guamensis, were old and eroded. The absence of living partulid snails, once apparently very abundant, is a warning of the possible extinction of the entire terrestrial snail fauna of Pohnpei. Introduction The snail family Partulidae includes approximately 120 species scattered DFURVV WKH LVODQGV RI WKH WURSLFDO 3DFLILF 2FHDQ 7KH YDVW PDMRULW\ a IDOO within the genus Partula and are distributed from the Northern Mariana Islands and Palau, in the west, to the Society Islands in the eastern tropical Pacific (Cowie 1992). -

Nan Madol (Federated States of Micronesia) No 1503

Technical Evaluation Mission An ICOMOS technical evaluation mission visited the Nan Madol property from 17 to 24 August 2015. (Federated States of Micronesia) Additional information received by ICOMOS No 1503 A copy of the proposed Bill adding to the Pohnpei Code to establish the Nan Madol Historic Preservation Trust together with a copy of the Pohnpei Code were provided to the mission expert, together with the brochure on the Nan Madol Archaeological Site and a research report on Official name as proposed by the State Party the Shoreline Change Phase 1 for Federated States of Nan Madol: Ceremonial Center of Eastern Micronesia Micronesia (FSM). Location A letter was sent by ICOMOS to the State Party on 23 Madolenihmw Municipality, Pohnpei Island September 2015 requesting an updated map showing all Pohnpei State numbered sites; clarification on protection of the buffer Federated States of Micronesia zone; a time schedule for passing the new Bill, and for the completion of the management plan. A response Brief description from the State Party was received on 18 November 2015 Created on a series of 99 artificial islets off the shore of and the information has been incorporated below. An Pohnpei Island, the remains of stone palaces, temples, interim report including a request for additional mortuaries and residential domains known as Nan Madol information was sent by ICOMOS to the State Party on represent the ceremonial centre of the Saudeleur 21 December 2015 following discussions with the State Dynasty. Reflecting an era of vibrant and intact Pacific Party by Skype on 2 December 2015 regarding the state Island culture the complex saw dramatic changes of of conservation of the property and a possible approach settlement and social organisation 1200-1500 CE. -

Infrastructure Development Plan (IDP)

Federated States of Micronesia INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN FY2004-FY2023 Prepared by: DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, COMMUNICATIONS & INFRASTRUCTURE MAY 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................v 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................1 2. Preparation of Infrastructure Development Plan .....................................................2 2.1 Historical Background...................................................................................... 2 2.2 Preparation of Draft Final Report.................................................................... 2 2.3 Final IDP Report .............................................................................................. 3 2.4 Formal Submission of the IDP.......................................................................... 3 2.5 Preparation of Final IDP Document ................................................................ 3 3. Planning Context......................................................................................................4 3.1 FSM Planning Framework ............................................................................... 4 3.2 Public Sector Investment Program ................................................................... 4 3.3 Public and Private Sector Management of Infrastructure................................ 5 3.4 National Government Infrastructure Priorities............................................... -

Federated States of Micronesia SBSAP

Pohnpei State Biodiversity Strategic Action Plan September 2004 r-- Table of contents Acknowledgements 2 Acronyms 4 Introduction 5 Map of Pohnpei State (with Areas of Biodiversity Significance) .9 Mission, Vision, Strategic Goals and Actions 10 Monitoring and Evaluation . 18 Implementation .19 Financing .19 Signatures (state and municipal leaders) 21 Acknowledgements This Action (Implementation) Plan, together with the FSM National Strategic Action Plan (NBSAP), provides the framework for biodiversity conservation, resource, waste, pollution and energy management in Pohnpei State for the next five years and beyond. The plan is the result of numerous consultations over two years with input from national, state, local and resource agency/organization leaders and community representatives. This Plan includes the most relevant strategies goals and actions for Pohnpei State's priority areas in biodiversity conservation. resource. waste, pollution and energy management. The people listed below deserve special recognition for their exceptional dedication and contributions to this plan. With their exceptional knowledge and vast experience in the areas, we feel that this plan contains the state's highest priority and most relevant strategic goals and actions. Finally, this plan and the extensive efforts that went into its development were made possible by the generous financial support of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Lt. Governor Jack E. Yakana Chairman, Pohnpei Resource Management Committee (PRMC) Consultant K_ostka, CSP Executive Director Advisory Team Jack E. Vakana, Pohnpei State Lt. Governor Youser Anson, DL&R Director Herson Anson, DL&R — DF Chief Bill Raynor, TNC Micronesia Program Director !limbers Adelino Lorens, SOEA DA Chief Kcnio Frank, Sapvvuahfik Chief Representative Ausen T. -

006, When I Arrived Jet Lagged and Unprepared for a Field Director Position with a Teaching Non-Profit Called Worldteach

EATING EMPIRE, GOING LOCAL: FOOD, HEALTH, AND SOVEREIGNTY ON POHNPEI, 1899-1986 BY JOSH LEVY DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Frederick Hoxie, Chair Professor Vicente Diaz Professor David Hanlon Professor Kristin Hoganson Associate Professor Martin Manalansan ABSTRACT Eating Empire, Going Local centers the island of Pohnpei, Micronesia in a global story of colonial encounter and dietary change. It follows Pohnpeians and Pohnpei’s outer Islanders in their encounters with Spain, Germany, Japan, and the United States, negotiating, adapting to, and resisting empire through food and food production. In the process, Pohnpei extended food’s traditional role as locus of political influence and used it to navigate deceptively transformative interventions in ecology, consumption, the market, and the body. Food became Pohnpei’s middle ground, one that ultimately fostered a sharp rise in rates of non-communicable diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension. The chapters draw on global commodity histories that converge on the island, of coconuts, rice, imported foods, and breadfruit. These foods illuminate the local and global forces that have delivered public health impacts and new political entanglements to the island. Eating Empire uses food and the analytic lenses it enables – from ecology and race to domesticity and sovereignty – as a tool to reimagine Pohnpei’s historical inter-imperial and contemporary political relationships from the bottom up. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The first time I saw Pohnpei was in the summer of 2006, when I arrived jet lagged and unprepared for a field director position with a teaching non-profit called WorldTeach. -

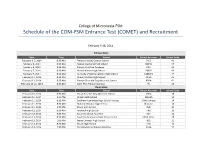

Schedule of the COM-‐FSM Entrance Test (COMET) and Recruitment

College of Micronesia-FSM Schedule of the COM-FSM Entrance Test (COMET) and Recruitment February 3-18, 2014 Pohnpei State Date Time School School Acronym School Code February 3-5, 2014 8:30 AM Pohnpei Islands Central School PICS 40 February 6, 2014 8:30 AM Nanpei Memorial High School NMHS 44 February 6, 2014 8:30 AM Calvary Christian Academy CCA 42 February 7, 2014 8:30 AM Madolenihmw High School PMHS 43 February 7, 2014 8:30 AM Our Lady of Mercy Catholic High School OLMCHS 47 February 11, 2014 8:30 AM Ohwa Christian High School OCHS 45 February 13, 2014 8:30 AM Pohnpei Seventh Day Adventist School PSDA 41 February 13-14, 2014 8:30 AM COM-FSM Pohnpei Campus PC 46 Chuuk State Date Time School School Acronym School Code February 10, 2014 8:30 AM Chuuk Seventh Day Adventist School CSDA 18 February 10, 2014 1:00 PM Mizpah High School Mizpah 15 February 11, 2014 8:30 AM Southern Namoneas High School-Tonoas SNHS-Tonoas 24 February 11, 2014 8:30 AM Nukuno Christian High School Nukuno 14 February 11, 2014 1:00 PM Xavier High School XHS 10 February 12, 2014 8:30 AM Faichuuk High School FHS 19 February 13, 2014 8:30 AM Saramen Chuuk Academy SCA 13 February 13, 2014 8:30 AM Southern Namoneas High School-Fefan SNHS-Fefan 24 February 13, 2014 1:00 AM Berea Christian High School BCS 11 February 14, 2014 8:30 AM Chuuk High School CHS 12 February 14, 2014 1:00 PM Pentecostal Lighthouse Academy PLHA 17 February 15, 2014 8:30 AM COM-FSM Chuuk Campus CC 21 Yap State Date Time School School Acronym School Code February 17, 2014 8:30 AM Yap Catholic High School YCHS 66 February 17, 2014 8:30 AM Outer Island High School (Ulithi) OIHS 63 February 17, 2014 8:30 AM Yap Seventh Day Adventist School YSDA 61 February 17, 2014 1:00 P.M. -

Media Release 27-2008

Embassy of the United States of America Kolonia Public Affairs Section P.O. Box 1286 Kolonia, Pohnpei, FM 96941 Telephone: (691) 320-2187 Fax: (691) 320-2186 Email: [email protected] September 09, 2008 Media Release No. 27-2008 U.S. NAVY MEDICAL PERSONNEL TREAT OVER 3,500 IN POHNPEI During the week of August 18-23, a visiting team of 26 military professionals from the United States Naval Hospital Ship USNS Mercy treated 3,567 patients in Pohnpei. This remarkable number represents over ten percent of the main island’s total population. These patients received primary medical care, optometry, dental, pharmacy and physical therapy services during the clinics. Mercy dental professionals performed a total of 247 tooth extractions, 127 of these on adults and 120 of them on children. Mercy optical professionals treated 903 patients and distributed 759 pair of prescription reading glasses and 345 pair of sunglasses. Mercy pharmacists saw 2,414 patients and filled 4,673 prescriptions. Patients who were screened and found to be in need of more serious health treatment (such as medical, surgical or orthodontic procedures) were referred to the Pohnpei Department of Health Services for treatment. In addition to the health care services delivered, two biotechnicians from the Mercy team also repaired the following medical equipment at the Pohnpei State Hospital: one blood bank refrigerator, one blood unit collector, one x-ray machine, two pulse oxymeters, four dental curing light units, one dental chair, four portable dental units, one dental air compressor and one calposcope (used for cervical checkups). They also diagnosed malfunctions and recommended parts to be ordered to fix the hospital’s embalming machine, dialysis machine and three additional dental curing light units. -

Taking Responsibility for Our Schools: a Series of Four Articles on Education in Micronesia. INSTITUTION Pacific Resources for Education and Learning, Honolulu, HI

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 467 541 RC 023 666 AUTHOR Hezel, Francis X. TITLE Taking Responsibility for Our Schools: A Series of Four Articles on Education in Micronesia. INSTITUTION Pacific Resources for Education and Learning, Honolulu, HI. Region XV Comprehensive Assistance Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-06-00 NOTE 49p.; Introduction by Hilda C. Heine. CONTRACT S283A950001 PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; Brain Drain; Community Involvement; Education Work Relationship; Educational Change; *Educational Objectives; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Pacific Islanders; Parent Participation; *Role of Education; *School Community Relationship; School Culture; *School Effectiveness IDENTIFIERS Exemplary Schools; *Federated States of Micronesia; Marshall Islands; Palau ABSTRACT Mobilizing communities to support educational improvements is one of the challenges confronting educators in the Freely Associated States (FAS), which consists of the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau. This booklet aims to establish a consensus on broad educational goals and to rebuild the sense of community ownership of schools that is missing today. "What Should Our Schools Be Doing?" describes conflicting views about whether education should provide for manpower training, cultural preservation, or academic skills, given the current poor academic achievement in the FAS and high rates of emigration to find work. It is suggested that a new education system can accommodate all three visions. "How Good Are Our Schools?" attempts to show the current status of schooling in each country but is hampered by incomplete data. Although test scores are the only data consistently available, there are other measures for school success. -

Lessons from the Field

Lessons from the Field The Traditional Monarch of Kitti in Pohnpei Addresses the High Rates of Non-Communicable Diseases through Local Policy Johnny Hadley, Jr. BA and Evonne Sablan MPA Abstract Pohnpeian high school students used cigarettes daily and 50.1% used smokeless tobacco.3 These unhealthy lifestyle practices Almost a quarter of Pohnpei’s population is overweight or obese, a major have led to high non-communicable disease (NCD) morbidity factor influencing a 2010 non-communicable diseases (NCD) emergency and mortality rates. In fact, the life expectancy in the FSM is declaration. The Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) ten years less than in the US.5 project in Pohnpei is implementing a culturally tailored policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) intervention to reduce NCDs through healthy nutrition projects. Through collaboration with traditional leaders and using traditional The 2010 US Affiliated Pacific Islands health emergency protocols, REACH succeeded in soliciting formal approval from a Traditional declaration called for regional, national, and local agencies Monarch to serve only healthy beverages during events at all traditional houses to mobilize and respond to reduce the incidences of NCDs in in the municipality. The Governor, in turn, also supported this initiative. This the region.6 Due to the state of emergency, the Pohnpei State project cultivated relationships with traditional and government leaders to Department of Health Services (DHS) has worked on health implement a culturally appropriate healthy nutrition PSE change intervention. interventions that impact the Pohnpeian population. Previously, Pohnpei State DHS implemented public health and behavior Keywords change programs, such as health education campaigns and exercise programs, which targeted individual change and were Micronesia, Pacific Islander, traditional leaders, nutrition non-sustaining. -

World Heritage Patrimoine Mondial 42

World Heritage 42 COM Patrimoine mondial Paris, 21 June 2018 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE / COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Forty-second session / Quarante-deuxième session Manama, Bahrain / Manama, Bahreïn 24 June - 4 July 2018 / 24 juin -4 juillet 2018 Item 7 of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List and/or on the List of World Heritage in Danger Point 7 de l’Ordre du jour provisoire: Etat de conservation de biens inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial et/ou sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril MISSION REPORT / RAPPORT DE MISSION Nan Madol: Ceremonial Centre of Eastern Micronesia (Federated States of Micronesia) (C 1503) Nan Madol : centre cérémoniel de la Micronésie orientale ( Etats fédérés de Micronésie) (C 1503) 16-25 January 2018 / 16-25 janvier 2018 REPORT ON THE WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE / ICOMOS REACTIVE MONITORING MISSION TO NAN MADOL: CEREMONIAL CENTRE OF EASTERN MICRONESIA (FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA) (1503) 16 TO 25 JANUARY 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND LIST OF RECOMMENDATIONS 1 BACKGROUND TO THE MISSION Inscription history Inscription criteria and Outstanding Universal Value Examination of the State of Conservation by