Archaeology in Suffolk 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suffolk County Council

Suffolk County Council Western Suffolk Employment Land Review Final Report May 2009 GVA Grimley Ltd 10 Stratton Street London W1J 8JR 0870 900 8990 www.gvagrimley.co.uk This report is designed to be printed double sided. Suffolk County Council Western Suffolk Employment Land Review Final Report May 2009 Reference: P:\PLANNING\621\Instruction\Clients\Suffolk County Council\Western Suffolk ELR\10.0 Reports\Final Report\Final\WesternSuffolkELRFinalReport090506.doc Contact: Michael Dall Tel: 020 7911 2127 Email: [email protected] www.gvagrimley.co.uk Suffolk County Council Western Suffolk Employment Land Review CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1 2. POLICY CONTEXT....................................................................................................... 5 3. COMMERCIAL PROPERTY MARKET ANALYSIS.................................................... 24 4. EMPLOYMENT LAND SUPPLY ANALYSIS.............................................................. 78 5. EMPLOYMENT FLOORSPACE PROJECTIONS..................................................... 107 6. BALANCING DEMAND AND SUPPLY .................................................................... 147 7. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS......................................................... 151 Suffolk County Council Western Suffolk Employment Land Review LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1 The Western Suffolk Study Area 5 Figure 2 Claydon Business Park, Claydon 26 Figure 3 Industrial Use in -

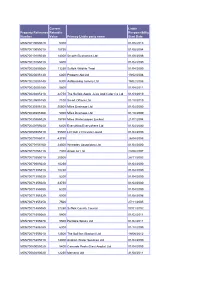

Property Reference Number Current Rateable Value Primary Liable

Current Liable Property Reference Rateable Responsibility Number Value Primary Liable party name Start Date MSN70010050020 5300 01/05/2013 MSN70010055010 10750 01/08/2004 MSN70010105030 14000 Stealth Electronics Ltd 01/06/2006 MSN70020155010 5800 01/04/2000 MSN70020205080 11250 Suffolk Wildlife Trust 01/04/2000 MSN70020205130 6300 Property Aid Ltd 19/02/2008 MSN70020205140 9300 Ashbocking Joinery Ltd 19/02/2008 MSN70020205180 5800 01/04/2011 MSN70020205210 42750 The Suffolk Apple Juice And Cider Co Ltd 01/03/2010 MSN70020505150 7100 Smart Offices Ltd 01/10/2010 MSN70030305130 20500 Miles Drainage Ltd 01/04/2000 MSN70030305360 5000 Miles Drainage Ltd 01/10/2000 MSN70030355020 19750 Miles Waterscapes Limited 21/07/2004 MSN70040155040 6400 Everything Everywhere Ltd 01/04/2000 MSN70050305010 55500 Lt/Cmdr J Chevalier-Guild 01/04/2000 MSN70070155011 43750 26/04/2005 MSN70070155100 24500 Wheatley Associates Ltd 01/04/2000 MSN70070155110 7000 Angel Air Ltd 20/08/2007 MSN70070355010 20500 26/11/2003 MSN70070505020 10250 01/04/2000 MSN70071305010 10250 01/04/2000 MSN70071305020 5200 01/04/2000 MSN70071355020 23750 01/04/2000 MSN70071355080 6200 01/04/2000 MSN70071355320 5000 01/08/2006 MSN70071355350 7500 27/11/2005 MSN70071455060 27250 Suffolk County Council 07/01/2002 MSN70071505060 5900 01/02/2011 MSN70071505070 9500 Portable Space Ltd 01/02/2011 MSN70071505150 6300 01/10/2009 MSN70071555010 13500 The Bull Inn (Bacton) Ltd 19/06/2012 MSN70071605010 14000 Anglian Water Services Ltd 01/04/2000 MSN70080055020 5400 Cascade Pools (East Anglia) Ltd -

Comments for Planning Application 1832/17

Comments for Planning Application 1832/17 Application Summary Application Number: 1832/17 Address: Land To The West Of Old Norwich Road And To The East Of The A14 Claydon Proposal: Outline Application (Access to be considered) - Erection of up to 315 dwellings, vehicular access to Old Norwich Road, public open space, and associated landscaping, engineering and infrastructure works Case Officer: Ben Elvin Customer Details Name: Mrs Suzanne Eagle Address: Valley View, Church Lane, Claydon Ipswich, Suffolk IP6 0EG Comment Details Commenter Type: Parish Council Stance: Customer objects to the Planning Application Comment Reasons: - Boundary Issues - Conflict with local plan - Drainage - In Conservation Area - Inadequate Access - Landscape Impact - Loss of Open Space - Loss of View - Out of Character - Sustainability - Traffic or Highways - Wildlife Comment:Claydon & Whitton Parish Council objects to this application for the following reasons:- 1. Whitton Rural, where the land on the application is situated, such a large development would be totally out of character in this rural area and the community will lose it's identity. 2. Loss of village status. Claydon/Barham's character is that of a village and building 315 houses in the agricultural belt between Ipswich and Claydon will blur the boundaries and set a dangerous precedent. 3. Old Ipswich Road must not under any circumstances be opened up as this will create a major traffic problem in Claydon. This road remaining closed retains the rural independence of Claydon/Barham from the Ipswich conurbation. 4. Increase in traffic. According to the developers own report the Bury Road junction (A1156) is set to exceed capacity by 2022. -

Joint Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Council Landscape Guidance August 2015

Joint Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Council Landscape Guidance August 2015 Joint Babergh and Mid Suffolk District Council Landscape Guidance 2015 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The landscape of Babergh and Mid Suffolk (South and North Suffolk) is acknowledged as being attractive and an important part of why people choose to live and work here. However current pressures for development in the countryside, and the changing agricultural and recreational practices and pressures, are resulting in changes that in some instances have been damaging to the local character and distinctiveness of the landscape. 1.1.1 Some development is necessary within the countryside, in order to promote a sustainable prosperous and vibrant rural economy. However, such development would be counterproductive if it were to harm the quality of the countryside/landscape it is set within and therefore the quality of life benefits, in terms of health and wellbeing that come from a rural landscape in good condition.1 1.1.2 The Council takes the view that there is a need to safeguard the character of both districts countryside by ensuring new development integrates positively with the existing character. Therefore, a Landscape Guidance has been produced to outline the main elements of the existing character and to outline broad principles that all development in the countryside will be required to follow. 1.1.3 Well designed and appropriately located development in the countryside can capture the benefits of sustainable economic development whilst still retaining and enhancing valuable landscape characteristics, which are so important to Babergh and Mid Suffolk. 1.1.4 The protection and enhancement of both districts landscape is essential not only for the intrinsic aesthetic and historic value that supports tourism and the economy for the area but also to maintain the quality of life for the communities that live in the countryside. -

Country Cottage with Far Reaching Views Birdsfield Cottage Henley

Country Cottage With Far Reaching Views Birdsfield Cottage STOWMARKET Henley Road 01449 257444 Akenham Ipswich Available 8am -10pm every day Suffolk IP6 0HG haart.co.uk £260,000 Freehold Ref: HRT037200550 A quirky former farm cottage with far reaching rural views offering three bedrooms and ample parking and storage. G``Character Features G``Three Bedrooms G``D/S Cloakroom G``Wood Burning Stove G``Open Plan Kitchen/Diner G``Far Reaching Views G``Multiple Storage Rooms G``Ample Parking Entrance Hall Master Bedroom 11'0" x 14'3" (3.35m x Double glazed front entrance door into hallway 4.34m) with obscure glass window to side aspect. Double glazed window to front aspect. Wall Exposed wooden floorboards. Further double mounted electric heater. glazed door leads into sitting room. Bedroom Three 8'4" x 10'3" (2.54m x Sitting Room 14'1" x 16'2" (4.29m x 4.93m) 3.12m) Double glazed window to front aspect. Feature Double glazed window to rear aspect. Raised unit fireplace with brick built chimney breast with accommodates single mattress utilising the space wooden mantle over and inset wood burning stove above the stairwell. and stone hearth. Exposed floorboards. Bedroom Two 8'5" x 10'9" (2.57m x 3.28m) Inner Hall 8'4" x 15'1" (2.54m x 4.6m) Double glazed window to rear aspect. Wall Exposed wooden floor boards. Wall mounted mounted electric heater. electric heater. Suffolk latch doors to under stairs cupboard and to large storage cupboard. Double Bathroom glazed window to rear aspect. Exposed pine Obscure glass window to rear aspect. -

Stowmarket Area Action Plan

Stowmarket Area Action Plan Mid Suffolk’s New Style Local Plan Adopted February 2013 1 Welcome Witamy Sveiki If you would like this document in another language or format, or if you require the services of an interpreter, please contact us. JeĪeli chcieliby PaĔstwo otrzymaü ten document w innym jĊzyku lub w innym Formacie albo jeĪeli potrzebna jest pomoc táumacza, to prosimy o kontakt z nami. Jei pageidaujate gauti šƳ dokumentą kita kalba ar kitu formatu, arba jei jums Reikia vertơjo paslaugǐ, kreipkitơs Ƴ mus. 0845 6 066 067 Stowmarket Area Action Plan Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Stowmarket and Surrounding Area - Past and Present 6 3 Vision and Spatial Strategy 9 4 General Policies 14 5 Shopping and Town Centre 20 Allocation for Mixed Use Development - The Station Quarter 29 6 Housing 33 Existing Residential Areas 38 Urban Fringe - New Communities 38 Surrounding Villages 44 Allocations for Housing 46 7 Employment 64 Industrial Commercial Corridor 71 Allocations for Employment 75 8 Transport and Connectivity 84 9 Natural Environment, Biodiversity and the Historic Environment 92 Natural Environment and Biodiversity 92 River Valleys 94 Historic Environment 97 10 Leisure, Recreation, Community Infrastructure and Green Open Spaces 99 11 Implementation and Monitoring 103 12 Appendix A - Infrastructure Delivery Programme 108 13 Appendix B - Mid Suffolk Local Plan policies superseded by the Stowmarket Area Action Plan 113 14 Appendix C - List of Stowmarket Area Action Plan policies 114 15 Appendix D - Background Evidence 116 16 Appendix E - Mid Suffolk District Council's Glossary of Terms 119 17 Appendix F - Stowmarket Area Action Plan Proposals Map 131 Mid Suffolk Stowmarket Area Action Plan (February 2013) Stowmarket Area Action Plan 1 Introduction Purpose and status of this document 1.1 The Stowmarket Area Action Plan (SAAP) is a formal planning document. -

Bosmere Gipping Valley Thredling Brook Cosford Thedwastre South

Stonham Stowmarket East Stow Thorney Earl Stonham Great Finborough Combs Ford Stowmarket Creeting St. Peter Crowfield Stonham Division Thredling Arrangements for Creeting St. Mary Badley Onehouse Thedwastre South Combs Needham Market County Gosbeck District Little Finborough Parish Proposed Electoral Needham Market Coddenham Division District/Borough Council Ward Hitcham Battisford Hemingstone Barking Darmsden Claydon & Barham Ringshall Bosmere North West Cosford Battisford & Ringshall Baylham Barham Wattisham Great Bricett Willisham Great Blakenham Nettlestead Cosford Gipping Valley Offton Claydon Blakenham Nedging-with-Naughton Little Blakenham Akenham Somersham Whitton 0 0.425 0.85 1.7 Whitton South East Cosford Kilometers Bramford Whitton Semer Elmsett Brook Bramford This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Hadleigh Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Whatfield Whitehouse Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and Flowton database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2020. Westbourne Semer Copdock & Washbrook Thredling Gosbeck Creeting St. Mary Thredling Needham Market Battisford Ashbocking Division Coddenham Arrangements for Hemingstone Gipping Valley Barking County Darmsden District Needham Market Parish Battisford & Ringshall Proposed Electoral Division Claydon & Barham Bosmere Henley District/Borough Barham Council Ward Baylham Witnesham Willisham Great Blakenham Grundisburgh & Wickham Market Nettlestead Gipping Valley Claydon Offton Akenham Blakenham Little Blakenham Carlford & Fynn Valley Somersham Whitton Westerfield Whitton Whitton Bramford Bramford Elmsett South East Cosford Flowton Westbourne St. Margaret's Castle Hill 0 0.375 0.75 1.5 Whitehouse St Margaret's Kilometers This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the Brook Westgate permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Burstall Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. -

November 2017

Stowmarket Town Council NatWest Current A/C List of Payments made between 01/11/2017 and 30/11/2017 Date Paid Payee Name Cheque Ref Amount Paid Transaction Detail 01/11/2017 Anglian Water Authority 01/11/17A 533.80 CC Water 08/07-07/10/17 01/11/2017 Anglian Water Authority 01/11/17B 50.32 OT Water 01/06-14/09/17 01/11/2017 Anglian Water Authority 01/11/17C 45.19 CEM Water 06/06-21/09/17 01/11/2017 Anglian Water Authority 01/11/17D 43.09 CEM Water 01/07-30/09/17 01/11/2017 Anglian Water Authority 01/11/17E 94.57 OS Water 14/06-30/09/17 01/11/2017 Anglian Water Authority 01/11/17F 12.10 TC Water Standing Charge 02/11/2017 Dairy Crest 02/11/17A 19.44 OS Milk Bill Oct 17 06/11/2017 Everything Everywhere Ltd 06/11/17A 116.54 COS Mobiles Oct 17 Akenham Furniture & Joinery 575.00 WS Fire Doors CCN Anglian Chemicals Ltd 248.56 REG, OS & CC Various Cleaning Materials Arco Limited 106.92 CC Polo, Fleece & Jackets Auditing Solutions Ltd 1,008.00 COS Audit 03-04/10/17 Blue Star Human Resources Ltd 122.58 COR HR Support 17/10/17 Chocolate Tiger Coffee Company Ltd 96.30 REG Coffee Oct 17 Ms C Draude 120.00 COR Clowning Recreation Ground Play Opening Churches Fire Security Limited 414.66 WS Alarm Installation CCN The Cinema Exhibitors Association Ltd 182.30 REG Music Licence 17/18 CinemaLive Limited 250.00 REG Carmen 14/09/17 C A Keeble 670.00 OT Various Training Operations Team East of England Cooperative Society 345.00 CEM Seeley Refund (Ex Rights) Dragon Security Systems 166.80 WS CCTV Cover 01/04-31/10/18 Entertainment One UK 146.20 REG Jungle Oct -

Mid Suffolk District Council CIL Neighbourhood Payments 11 April 2016 to 30 September 2016

Mid Suffolk District Council CIL Neighbourhood Payments 11 April 2016 to 30 September 2016 Neighbourhood CIL 123 Zone Admin CIL List Akenham Parish Meeting 0.00 0.00 Ashbocking Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Ashfield-Cum-Thorpe Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Aspall Parish Meeting 0.00 0.00 Bacton Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Badley Parish Meeting 0.00 0.00 Badwell Ash Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Barham Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Barking Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Battisford Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Baylham Parish Meeting 0.00 0.00 Bedfield Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Bedingfield Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Beyton Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Botesdale Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Braiseworth Parish Meeting 0.00 0.00 Bramford Parish Council 991.07 2,973.21 15,857.12 Brome & Oakley Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Brundish Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Buxhall Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Claydon & Whitton Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Coddenham Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Combs Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Cotton Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Creeting St Mary Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Creeting St Peter Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Crowfield Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Darmsden Parish Meeting 0.00 0.00 Debenham Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Denham Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Drinkstone Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Earl Stonham Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Elmswell Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Eye Town Council 0.00 0.00 Felsham Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Finningham Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Flowton Parish Meeting 0.00 0.00 Framsden Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Fressingfield Parish Council 0.00 0.00 Gedding Parish Meeting 0.00 0.00 Gislingham -

Summary of "Call for Ideas"

THE IPSWICH NORTHERN FRINGE SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENT THE “CALL FOR IDEAS”: A SUMMARY During April and May 2012 Ipswich Borough Council carried out informal consultation in the form of a “call for ideas” relating to the proposed development of the Ipswich Northern Fringe and the intended preparation of a Planning Brief in the form of a Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) needed to guide this development. The “call for ideas” was advertised in the Council’s newspaper, The Angle and on the Council’s website. Known residents groups (Save or Country Spaces and the Northern Fringe Protection Group), the Ipswich Society, and Westerfield Parish Council were contacted directly and asked to provide a response. A newsletter (including a piece on “the call for ideas”) was sent out to all on the Local Development Framework mailing list plus copies to the relevant Parish Councils (ie Westerfield, Tuddenham, Claydon and Whitton, Akenham, and Rushmere. Adjoining District Councils were notified in writing of the intention to prepare the SPD and invited to make any initial comments, with an offer of a meeting if required. Various agency stakeholders were formally notified (by letter or email) of the intention to prepare the SPD and invited to make any initial comments, and identify any key issues. Agencies were also invited to attend a group briefing meeting facilitated by David Lock Associates at the Borough Council offices. A separate report on agency responses is being prepared. The agencies consulted were as follows:- Environment Agency Anglian Water Suffolk County Council NHS Suffolk (formerly Suffolk PCT) Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust Suffolk Constabulary. -

Appendix 25.2 Onshore Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Gazetteers

East Anglia THREE Appendix 25.2 Onshore Archaeology And Cultural Heritage Gazetteers Environmental Statement Volume 3 Document Reference – 6.3.25 (2) Author – Wessex Archaeology East Anglia THREE Limited Date – November 2015 Revision History – Revision A Environmental Statement East Anglia THREE Offshore Windfarm Appendix 25.2 November 2015 This Page is Intentionally Blank Environmental Statement East Anglia THREE Offshore Windfarm Appendix 25.2 November 2015 Table of Contents 1 Onshore Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Gazetteers ................................ 1 1.1 Gazetteer of Designated Heritage Assets Within the Study Area .................... 1 1.1.1 National Heritage List for England – Listed Buildings Within the Study Area ...... 1 1.1.2 National Heritage List for England – Registered Parks and Gardens Within the Study Area............................................................................................................. 4 1.1.3 National Heritage List for England – Scheduled Monuments Within the Study Area ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Gazetteer of Archaeological Records (Based on Suffolk HER) Within the Study Area ............................................................................................................. 5 1.2.1 Suffolk Historic Environment Record – Archaeology ........................................... 5 1.2.2 Archaeology Records Identified During RSK Walkover Survey .......................... 55 1.3 -

APPENDIX 3 Consultees for the Public Consultation on the Draft Public

APPENDIX 3 Consultees for the public consultation on the draft Public Open Space SPD Private individuals from our Local Plan database All Ipswich Borough Council Councillors The following Organisations/Businesses: Housebuilders Federation Friends of the Earth The Wellington Centre Hanover Housing Association Suffolk School of Samba Richard Jackson Partnership Ltd Broadway Malyan Planning London Road Allotment Holders Orwell Veterinary Group Pegasus Group St Pancras Catholic Primary School The Willows Primary School St Mark's Catholic Primary School Rushmere Hall Primary School Broke Hall Community Primary School Ipswich & Suffolk Council for Racial Equality Anchor Trust Chantry High School and Sixth Form Centre Suffolk Association of Local Councils Sanctuary Housing Association Witnesham Pariochial Church Council Strutt & Parker Ipswich Community Radio Chinese Welfare and Support Stanley Bragg Partnership Ltd The Kesgrave Covenant Limited SBRC - Ipswich Museum David Walker Chartered Surveyors Back Hamlet Ipswich, Allotment Holders Association St John Ambulance Whitehouse Community Infants School Bacton Gospel Hall Trust Italian Association Ryan Elizabeth Holdings The Woodland Trust Ipswich Society Ipswich Preparatory School Bethesda Community Charitable Trust ISCRE Orchard Street Health Centre Whitton Residents Association Ipswich Caribbean Association Save Our Country Spaces Savills (L&P) Ltd on behalf of Turnstone Estates Savills Maidenhall Tenants' Association Associated British Ports