A STUDY on BRIEF ACCOUNT on GUPTA DYNASTY - SOME ACHIEVEMENTS in INDIA Dr.U.Krishna Mohan, C.Ayyavarappa, Asst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes Posted On April 28, 2020 By Cgpsc.Info Home » CGPSC Notes » History Notes » Gupta Empire and Their Rulers Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – The Gupta period marks the important phase in the history of ancient India. The long and e¸cient rule of the Guptas made a huge impact on the political, social and cultural sphere. Though the Gupta dynasty was not widespread as the Maurya Empire, but it was successful in creating an empire that is signiÛcant in the history of India. The Gupta period is also known as the “classical age” or “golden age” because of progress in literature and culture. After the downfall of Kushans, Guptas emerged and kept North India politically united for more than a century. Early Rulers of Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) :- Srigupta – I (270 – 300 C.E.): He was the Ûrst ruler of Magadha (modern Bihar) who established Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) with Pataliputra as its capital. Ghatotkacha Gupta (300 – 319 C.E): Both were not sovereign, they were subordinates of Kushana Rulers Chandragupta I (319 C.E. to 335 C.E.): Laid the foundation of Gupta rule in India. He assumed the title “Maharajadhiraja”. He issued gold coins for the Ûrst time. One of the important events in his period was his marriage with a Lichchavi (Kshatriyas) Princess. The marriage alliance with Kshatriyas gave social prestige to the Guptas who were Vaishyas. He started the Gupta Era in 319-320C.E. Chandragupta I was able to establish his authority over Magadha, Prayaga,and Saketa. Calendars in India 58 B.C. -

The Gupta Empire: an Indian Golden Age the Gupta Empire, Which Ruled

The Gupta Empire: An Indian Golden Age The Gupta Empire, which ruled the Indian subcontinent from 320 to 550 AD, ushered in a golden age of Indian civilization. It will forever be remembered as the period during which literature, science, and the arts flourished in India as never before. Beginnings of the Guptas Since the fall of the Mauryan Empire in the second century BC, India had remained divided. For 500 years, India was a patchwork of independent kingdoms. During the late third century, the powerful Gupta family gained control of the local kingship of Magadha (modern-day eastern India and Bengal). The Gupta Empire is generally held to have begun in 320 AD, when Chandragupta I (not to be confused with Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Mauryan Empire), the third king of the dynasty, ascended the throne. He soon began conquering neighboring regions. His son, Samudragupta (often called Samudragupta the Great) founded a new capital city, Pataliputra, and began a conquest of the entire subcontinent. Samudragupta conquered most of India, though in the more distant regions he reinstalled local kings in exchange for their loyalty. Samudragupta was also a great patron of the arts. He was a poet and a musician, and he brought great writers, philosophers, and artists to his court. Unlike the Mauryan kings after Ashoka, who were Buddhists, Samudragupta was a devoted worshipper of the Hindu gods. Nonetheless, he did not reject Buddhism, but invited Buddhists to be part of his court and allowed the religion to spread in his realm. Chandragupta II and the Flourishing of Culture Samudragupta was briefly succeeded by his eldest son Ramagupta, whose reign was short. -

Mythological Concepts of Pre Vedic Mithila in Received: 28-06-2020 Accepted: 30-07-2020 Migration

International Journal of History 2020; 2(2): 81-83 E-ISSN: 2706-9117 P-ISSN: 2706-9109 IJH 2020; 2(2): 81-83 Topic - Mythological concepts of pre vedic Mithila in Received: 28-06-2020 Accepted: 30-07-2020 migration Dr. Swati Kumari P.S.- L.N.M.U. Campus Dr. Swati Kumari Dist- Darbhanga, Bihar, India DOI: https://doi.org/10.22271/27069109.2020.v2.i2b.48 Abstract Evetually the aboriginals attracted by the settled life of these vedic immigrants drew nearer to them and started co-operating with them participation in their agricultural operations and Ultimately were so to say, absorbed in the lowest rung to their society. It presented a contrast to the panorama of religious and philosophical thought of greater Mithila. The period discussed so far as we the immigration of many people into Mithila. The videha, Licchani vajji and a host of other Aryan as well as non-Aryan tribes entered in succession the virgin land of Mithila and settled there comfortable. Perhaps granting of land free of such king in Mithila. Keywords: Mithila, agriculture, immigrants, migrate, migration, Magadha, power Introduction Pre-vedic Mithila was inhabited by a number of tribes belonging to two groups. The Kiratas in the north and the Kolas in the south. They dwelt in forest and marshy land and lived on hunting and fishing. Near about 1500-1600bc. One Videghamathab. With a host of his learned priests and followers crossed the river Sadanira (Modem Gandak) from the west and [1] established his kingdom in Mithila . These vedic people new agriculture and cattle rearing and possessed a high standard of rural civilization and culture. -

The Hephthalite Numismatics

THE HEPHTHALITE NUMISMATICS Aydogdy Kurbanov 1. Introduction Arabic – Haital, Hetal, Heithal, Haiethal, Central Asia and neighbouring countries have a Heyâthelites. In Arabic sources the Hephtha- very old and rich history. A poorly-studied and in- lites, though they are mentioned as Haitals, tricate period of this region is the early medieval are sometimes also refered to as Turks. period (4th - 6th centuries AD). During this time, In the 4th - 6th centuries AD the territory of Cen- “The Great movement of peoples”, the migration tral Asia included at least four major political en- of nomadic peoples (Huns) from Asia to Europe, tities, among them Kushans, Chionites, Kidarites, took place. In South and Central Asia, great em- and Hephthalites. Discussions about the origins pires existed, including Sasanian Iran, Gupta and of these peoples still continue. Ideas vary from some small states. Across Central Asia, mysteri- the Hephthalites considered as part of the Hun ous new peoples appeared: the Hephthalites, the confederation to different other origins. It is also Kidarites and the Chionites, among others. Their uncertain whether the Hephthalites, the Kidarites origins are still debated. Some scholars suppose and the Chionites had a common or different ori- that they were part of a Hun confederation, while gins – that is, are they three branches of the same others suppose they had different origins. ethnic group or are they culturally, linguistically, Generally, the early research on the Hephthalites and genetically distinct from one another? was based only on written sources. They were The Hephthalites are well represented in their mentioned for the fi rst time in AD 361 at the siege coins. -

Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Mindfulness Studies Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-6-2020 Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Meill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Meill, Kyung Peggy, "Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā" (2020). Mindfulness Studies Theses. 29. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mindfulness Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ i Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Kim Meill Lesley University May 2020 Dr. Melissa Jean and Dr. Andrew Olendzki DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ ii Abstract A literary work provides a window into the world of a writer, revealing her most intimate and forthright perspectives, beliefs, and emotions – this within a scope of a certain time and place that shapes the milieu of her life. The Therīgāthā, an anthology of 73 poems found in the Pali canon, is an example of such an asseveration, composed by theris (women elders of wisdom or senior disciples), some of the first Buddhist nuns who lived in the time of the Buddha 2500 years ago. The gathas (songs or poems) impart significant details concerning early Buddhism and some of its integral elements of mental and spiritual development. -

History of Dev ( Deo/Chaudhary )

History of Dev ( Deo/Chaudhary ) .... Before Nepal's emergence as a nation in the later half of the 18th century, the designation 'Nepal' was largely applied only to the Kathmandu Valley and its surroundings. Thus, up to the unification of the country, Nepal's recorded history is largely that of the Kathmandu Valley. References to Nepal in the Mahabharata epic, in Puranas and in Buddhist and Jaina scriptures establish the country's antiquity as an independent political and territorial entity. The oldest Vamshavali or chronicle, the Gopalarajavamsavali, was copied from older manuscripts during the late 14th century, is a fairly reliable basis for Nepal's ancient history. The Vamshavalis mention the rule of several dynasties the Gopalas, the Abhiras and the Kiratas—over a stretch of millennia. However, no historical evidence exists for the rule of these legendary dynasties. The documented history of Nepal begins with the Changu Narayan temple inscription of King Manadeva I (c. 464–505 AD) of the Licchavi dynasty. During the time of Gautama Buddha, the kings of the Lichchhavi dynasty were ruling over Baisali (Muzaffarpur, in modern Bihar in India). Baisali had a partly democratic form of government. According to the later inscription by King Jaya Dev II, Supushpa was the founder of the dynasty, but he was defeated by Ajatashatru, the powerful Magadha king, in the fifth century BC. When the kings of the Kushan empire became powerful in India, the Lichchhavis migrated to Nepal. The twenty-fourth descendant of King Supushpa, Jaya Dev II, re-established the rule of the Lichchhavis in Nepal. -

Book Reviews

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 3 Number 2 Article 11 1983 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 1983. Book Reviews. HIMALAYA 3(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol3/iss2/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VU. REVIEWS Slusser, Mar y Shepherd. Nepal Mandala- A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley. 2 Vols . Princeton: 1982 Princeton University Press. Maps, dra wings and plans, 1 color plate, 600 bla ck and white plates,appendices, bibliogra phy, index. xix, 491 pp. $1 25.00 Reviewed by : Ronald M. Bernier University of Colorado In plate 500 of this long-awaited study, Dipankara Buddha is shown by Mary Shepherd Slusser in the form of an over life-sized portable sculpture and "mask," with man inside, walking down a Bhaktapur street at the time of the Panch- dan festival. Like this remarkable photograph, Nepal Mandala, the product of nearly 15 years of research in Nepal, presents works of art and architecture in the full context of human life, land, and time. It is a precisely documented reference work and a remarkable account of history, but it is also a lively study that brings together the earthly and heavenly occupants of the Nepalese universe. -

An Empirical Analysis with Special

Airo International Research Journal January, 2017 Volume X, ISSN: 2320-3714 Airo International Research Journal January, 2017 Volume X, ISSN: 2320-3714 Urban Life During Gupta Period; A social Perspective Submitted by Mrs. NEENA Research Scholar, Sunrise University Gupta Empire By the fourth century A.D., political and military turmoil destroyed the Kushan empire in the north and many kingdoms in the south India. At this juncture, India was invaded by a series of foreigners and barbarians or Mlechchhas from the north western frontier region and central Asia. It signaled the emergance of a leader, a Magadha ruler, Chandragupta I. Chandragupta successfully combated the foreign invasion and laid foundation of the great Gupta dynasty, the emperors of which ruled for the next 300 years, bringing the most prosperous era in Indian history. The reign of Gupta emperors can truly be considered as the golden age of classical Indian history. Srigupta I (270-290 AD) who was perhaps a petty ruler of Magadha (modern Bihar) established Gupta dynasty with Patliputra or Patna as its capital. He was succedded by his son Ghatotkacha (290-305 AD). Ghatotkacha was succeeded by his son Chandragupta I (305-325 AD) who strengthened his kingdom by matrimonial alliance with the powerful family of Lichchavi who were rulers of Mithila. His marriage to Lichchhavi princess Kumaradevi, brought an enormous power, resources and prestige. He took advantage of the situation and occupied whole of fertile Gangetic valley. Chandragupta I eventually assumed the title of Maharajadhiraja (emperor) in formal coronation. Samudragupta (335 - 380 AD) succedded his father Chandragupta I. -

Unit 3 the Age of Empires: Guptas and Vardhanas

SPLIT BY - SIS ACADEMY www.tntextbooks.inhttps://t.me/SISACADEMYENGLISHMEDIUM Unit 3 The Age of Empires: Guptas and Vardhanas Learning Objectives • To know the establishment of Gupta dynasty and the empire-building efforts of Gupta rulers • To understand the polity, economy and society under Guptas • To get familiar with the contributions of the Guptas to art, architecture, literature, education, science and technology • To explore the signification of the reign of HarshaVardhana Introduction Sources By the end of the 3rd century, the powerful Archaeological Sources empires established by the Kushanas in the Gold, silver and copper coins issued north and Satavahanas in the south had by Gupta rulers. lost their greatness and strength. After the Allahabad Pillar Inscription of decline of Kushanas and Satavahanas, Samudragupta. Chandragupta carved out a kingdom and The Mehrauli Iron Pillar Inscription. establish his dynastic rule, which lasted Udayagiri Cave Inscription, Mathura for about two hundred years. After the Stone Inscription and Sanchi Stone downfall of the Guptas and thereafter and Inscription of Chandragupta II. interregnum of nearly 50 years, Harsha of Bhitari Pillar Inscription of Vardhana dynasty ruled North India from Skandagupta. 606 to 647 A.D (CE). The Gadhwa Stone Inscription. 112 VI History 3rd Term_English version CHAPTER 03.indd 112 22-11-2018 15:34:06 SPLIT BY - SIS ACADEMY www.tntextbooks.inhttps://t.me/SISACADEMYENGLISHMEDIUM Madubhan Copper Plate Inscription Lichchhavi was an old gana–sanga and Sonpat Copper Plate its territory lay between the Ganges and Nalanda Inscription on clay seal the Nepal Terai. Literary Sources Vishnu, Matsya, Vayu and Bhagavata Samudragupta (c. -

The Achievements of the Gupta Empire 18.1 Introduction in Chapter 17, You Learned How India Was Unified for the First Time Under the Mauryan Empire

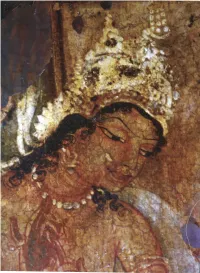

CHAPTER ^ An artist of the Gupta Empire painted this delicate image of the Buddha. The Achievements of the Gupta Empire 18.1 Introduction In Chapter 17, you learned how India was unified for the first time under the Mauryan Empire. In this chapter, you will explore the next great Indian empire, the Gupta Empire. The Guptas were a line of rulers who ruled much of India from 320 to 550 C.E. Many historians have called this period a golden age, a time of great prosperity and achievement. Peaceful times allow people to spend time thinking and being creative. During nonpeaceful times, people are usually too busy keeping themselves alive to spend time on inventions and artwork. For this reason, a number of advances in the arts and sciences came out during the peaceful golden age of the Gupta Empire. These achievements have left a lasting mark on the world. Archeologists have made some amazing discoveries that have helped us learn about the accom- plishments of the Gupta Empire. For example, they have unearthed palm-leaf books that were created about 550 C.E. Palm-leaf books often told religious stories. These stories are just one of many kinds of literature that Indians created under the Guptas. Literature was one of several areas of great accomplishment during India's Golden Age. In this chapter, you'll learn more about the rise of the Gupta Empire. Then Use this illustration of a palm-leaf book as a graphic you'll take a close look at seven organizer to help you learn more about Indian achieve- achievements that came out of ments during the Gupta Empire. -

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha)

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Ihsan Ali Muhammad Naeem Qazi Hazara University Mansehra NWFP – Pakistan 2008 Uploaded by [email protected] © Copy Rights reserved in favour of Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Editors: Ihsan Ali* Muhammad Naeem Qazi** Price: US $ 20/- Title: Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Frontispiece: Buddha Visiting Kashyapa Printed at: Khyber Printers, Small Industrial Estate, Kohat Road, Peshawar – Pakistan. Tel: (++92-91) 2325196 Fax: (++92-91) 5272407 E-mail: [email protected] Correspondence Address: Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Website: hu.edu.pk E-mail: [email protected] * Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Currently Vice Chancellor, Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan ** Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan CONTRIBUTORS 1. Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, Vice Chancellor Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan 2. Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 3. Ihsanullah Jan, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 4. Muhammad Ashfaq, University Museum, Hazara University 5. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 6. Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 7. Muhammad Imran Khan, Archaeologist, Charsadda, Pakistan 8. Muhammad Haroon, Archaeologist, Mardan, Pakistan III ABBREVIATIONS A.D.F.C. Archaeology Department, Frontier Circle A.S.I. Archaeological Survery of India A.S.I.A.R. Archaeological Survery of India, Annual Report D.G.A. Director General of Archaeology E.G.A.C. Exhibition of the German Art Council I.G.P. Inspector General Police IsMEO Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente P.M. -

"MAGIC BOOK" GK PDF in English

www.gradeup.co www.gradeup.co Content 1. Bihar Specific General Knowledge: • History of Bihar • Geography of Bihar • Tourism in Bihar • Mineral & Energy Resources in Bihar • Industries in Bihar • Vegetation in Bihar • National Park & Wildlife Sanctuaries in Bihar • First in Bihar • Important Tribal Revolt in Bihar • Bihar Budget 2020-21 2. Indian History: • Ancient India • Medieval India • Modern India 3. Geography: 4. Environment: 5. Indian Polity & Constitution: 6. Indian Economy: 7. Physics: 8. Chemistry: 9. Biology: www.gradeup.co HISTORY OF BIHAR • The capital of Vajji was located at Vaishali. • It was considered the world’s first republic. Ancient History of Bihar Licchavi Clan STONE AGE SITES • It was the most powerful clan among the • Palaeolithic sites have been discovered in Vajji confederacy. Munger and Nalanda. • It was situated on the Northern Banks of • Mesolithic sites have been discovered from Ganga and Nepal Hazaribagh, Ranchi, Singhbhum and Santhal • Its capital was located at Vaishali. Pargana (all in Jharkhand) • Lord Mahavira was born at Kundagram in • Neolithic(2500 - 1500 B.C.) artefacts have Vaishali. His mother was a Licchavi princess been discovered from Chirand(Saran) and (sister of King Chetaka). Chechar(Vaishali) • They were later absorbed into the Magadh • Chalcolithic Age items have been discovered Empire by Ajatshatru of Haryanka dynasty. from Chirand(Saran), Chechar(Vaishali), • Later Gupta emperor Chandragupta married Champa(Bhagalpur) and Taradih(Gaya) Licchavi princess Kumaradevi. MAHAJANAPADAS Jnatrika Clan • In the Later Vedic Age, a number of small • Lord Mahavira belonged to this clan. His kingdoms emerged. 16 monarchies and father was the head of this clan. republics known as Mahajanapadas stretched Videha Clan across Indo-Gangetic plains.