Cultural Heritage Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediating the Imaginary and the Space of Encounter in the Papuan Gulf Dario Di Rosa

7 Mediating the imaginary and the space of encounter in the Papuan Gulf Dario Di Rosa Writing about the 1935 Hides–O’Malley expedition in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, the anthropologist Edward Schieffelin noted that Europeans ‘had a well-prepared category – “natives” – in which to place those people they met for the first time, a category of social subordination that served to dissipate their depth of otherness’.1 However, this category was often nuanced by Indigenous representations of neighbouring communities, producing significant effects in shaping Europeans’ understanding of their encounters. Analysing the narrative produced by Joseph Beete Jukes,2 naturalist on Francis Price Blackwood’s voyage of 1842–1846 on HMS Fly, I demonstrate the crucial role played by Torres Strait Islanders as mediators from afar of European encounters with Papuans along the coast of the Gulf of 1 Schieffelin and Crittenden 1991: 5. 2 Jukes 1847. As Beer (1996) shows, the viewing position of on-board scientists during geographical explorations was a particular one, led by their interests (see, from a different perspective, Fabian (2000) on the relevance of ‘natural history’ as episteme of accounts of explorations). This is a reminder of the high degree of social stratification within the ‘European’ micro-social community of the ship’s crew, a social hierarchy that shaped the texts available to the historians. Although he does not treat the problem of social stratification as such, see Thomas 1994 for a well-argued discussion about the different projects that guided various colonial actors. See also Dening 1992 for vivid case of power relations in the micro-social cosmos of a ship. -

Torresstrait Islander Peoples' Connectiontosea Country

it Islander P es Stra eoples’ C Torr onnec tion to Sea Country Formation and history of Intersection of the Torres Strait the Torres Strait Islands and the Great Barrier Reef The Torres Strait lies north of the tip of Cape York, Torres Strait Islanders have a wealth of knowledge of the marine landscape, and the animals which inhabit it. forming the northern most part of Queensland. Different marine life, such as turtles and dugong, were hunted throughout the Torres Strait in the shallow waters. Eighteen islands, together with two remote mainland They harvest fish from fish traps built on the fringing reefs, and inhabitants of these islands also embark on long towns, Bamaga and Seisia, make up the main Torres sea voyages to the eastern Cape York Peninsula. Although the Torres Strait is located outside the boundary of the Strait Islander communities, and Torres Strait Islanders Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, it is here north-east of Murray Island, where the Great Barrier Reef begins. also live throughout mainland Australia. Food from the sea is still a valuable part of the economy, culture and diet of Torres Strait Islander people who have The Torres Strait Islands were formed when the land among the highest consumption of seafood in the world. Today, technology has changed, but the cultural use of bridge between Australia and Papua New Guinea the Great Barrier Reef by Torres Strait Islanders remains. Oral and visual traditional histories link the past and the was flooded by rising seas about 8000 years ago. present and help maintain a living culture. -

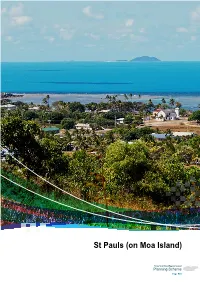

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

Navigating Boundaries: the Asian Diaspora in Torres Strait

CHAPTER TWO Tidal Flows An overview of Torres Strait Islander-Asian contact Anna Shnukal and Guy Ramsay Torres Strait Islanders The Torres Strait Islanders, Australia’s second Indigenous minority, come from the islands of the sea passage between Queensland and New Guinea. Estimated to number at most 4,000 people before contact, but reduced by half by disease and depredation by the late-1870s, they now number more than 40,000. Traditional stories recount their arrival in waves of chain migration from various islands and coastal villages of southern New Guinea, possibly as a consequence of environmental change.1 The Islanders were not traditionally unified, but recognised five major ethno-linguistic groups or ‘nations’, each specialising in the activities best suited to its environment: the Miriam Le of the fertile, volcanic islands of the east; the Kulkalgal of the sandy coral cays of the centre; the Saibailgal of the low mud-flat islands close to the New Guinea coast; the Maluilgal of the grassy, hilly islands of the centre west; and the Kaurareg of the low west, who for centuries had intermarried with Cape York Aboriginal people. They spoke dialects of two traditional but unrelated languages: in the east, Papuan Meriam Mir; in the west and centre, Australian Kala Lagaw Ya (formerly called Mabuiag); and they used a sophisticated sign language to communicate with other language speakers. Outliers of a broad Melanesian culture area, they lived in small-scale, acephalous, clan-based communities and traded, waged war and intermarried with their neighbours and the peoples of the adjacent northern and southern mainlands. -

How Torres Strait Islanders Shaped Australia's Border

11 ‘ESSENTIALLY SEA‑GOING PEOPLE’1 How Torres Strait Islanders shaped Australia’s border Tim Rowse As an Opposition member of parliament in the 1950s and 1960s, Gough Whitlam took a keen interest in Australia’s responsibilities, under the United Nations’ mandate, to develop the Territory of Papua New Guinea until it became a self-determining nation. In a chapter titled ‘International Affairs’, Whitlam proudly recalled his government’s steps towards Papua New Guinea’s independence (declared and recognised on 16 September 1975).2 However, Australia’s relationship with Papua New Guinea in the 1970s could also have been discussed by Whitlam under the heading ‘Indigenous Affairs’ because from 1973 Torres Strait Islanders demanded (and were accorded) a voice in designing the border between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Whitlam’s framing of the border issue as ‘international’, to the neglect of its domestic Indigenous dimension, is an instance of history being written in what Tracey Banivanua- Mar has called an ‘imperial’ mode. Historians, she argues, should ask to what extent decolonisation was merely an ‘imperial’ project: did ‘decolonisation’ not also enable the mobilisation of Indigenous ‘peoples’ to become self-determining in their relationships with other Indigenous 1 H. C. Coombs to Minister for Aboriginal Affairs (Gordon Bryant), 11 April 1973, cited in Dexter, Pandora’s Box, 355. 2 Whitlam, The Whitlam Government, 4, 10, 26, 72, 115, 154, 738. 247 INDIGENOUS SELF-determinatiON IN AUSTRALIA peoples?3 This is what the Torres Strait Islanders did when they asserted their political interests during the negotiation of the Australia–Papua New Guinea border, though you will not learn this from Whitlam’s ‘imperial’ account. -

Torres Strait Regional Economic Investment Strategy, 2015-2018 Phase 1: Regional Business Development Strategy

Page 1 Torres Strait Regional Economic Investment Strategy, 2015-2018 Phase 1: Regional Business Development Strategy A Framework for Facilitating Commercially-viable Business Opportunities in the Torres Strait September 2015 Page 2 This report has been prepared on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). It has been prepared by: SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd ACN 109 471 936 ABN 74 716 136 132 PO Box 45 The Gap Queensland 4061 p: (07) 3312 2375 m: 0410 550 272 e: [email protected] w: www.sashalennon.com.au and Workplace Edge Pty Ltd PO Box 437 Clayfield Queensland 4011 p (07) 3831 7767 m 0408 456 632 e: [email protected] w: www.workplaceedge.com.au Disclaimer This report was prepared by SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd and Workplace Edge Pty Ltd on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). It has been prepared on the understanding that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to its use and interpretation. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith. SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd, Workplace Edge Pty Ltd and the authors of this report are not liable to any person or entity taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to above. Photo image sources: © SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd Page 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A New Approach to Enterprise Assistance in the Torres Strait i A Plan of Action i Recognising the Torres Strait Region’s Unique Challenges ii -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Torres Strait Islanders: a New Deal

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: A NEW DEAL A REPORT ON GREATER AUTONOMY FOR TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Affairs August 1997 Canberra Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISBN This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs and printed by AGPS Canberra. The cover was produced in the AGPS design studios. The graphic on the cover was developed from a photograph taken on Yorke/Masig Island during the Committee's visit in October 1996. CONTENTS FOREWORD ix TERMS OF REFERENCE xii MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE xiii GLOSSARY xiv SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS xv CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE.......................................................................................................................................1 CONDUCT OF THE INQUIRY ......................................................................................................................................1 SCOPE OF THE REPORT.............................................................................................................................................2 PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS .................................................................................................................................3 Commonwealth-State Cooperation ....................................................................................................................3 -

Card Operated Meter Information

Purchasing a power card for your card-operated meter Power cards are available from the following sales outlets: Community Retail Agent Address Arkai (Kubin) Community T.S.I.R.C. - Kubin KUBIN COMMUNITY, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Arkai (Kubin) Community CEQ - Kubin IKILGAU YABY RD, KUBIN VILLAGE, MOA ISLAND QLD 4875 Aurukun Island & Cape 39 KANG KANG RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Aurukun Supermarket Aurukun Kang Kang Café 502 KANG KAND RD, AURUKUN QLD 4892 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Badu Hotel 199 NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island Island & Cape Badu MAIRU ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Supermarket (Bottom Shop) Badu (Mulgrave) Island J & J Supermarket 341 CHAPMAN ST, BADU ISLAND QLD (Top Shop) 4875 Badu (Mulgrave) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Badu NONA ST, BADU ISLAND QLD 4875 Bamaga Bamaga BP Service AIRPORT RD, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Station Bamaga Cape York Traders 201 LUI ST, BAMAGA QLD 4876 – Bamaga Store Bamaga CEQ – Bamaga 105 ADIDI AT, BAMAGA QLD 4876 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island CEQ – Boigu TOBY ST, BOIGU QLD 4875 Supermarket Boigu (Talbot) Island T.S.I.R.C. - Boigu 66 CHAMBERS ST, BOIGU ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) Daido Tavern PILOT ST, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Darnley Island (Erub) T.S.I.R.C. - Darnley COUNCIL OFFICE, DARNLEY ISLAND QLD 4875 Dauan Island (Mt CEQ - Dauan MAIN ST, DAUAN ISLAND QLD 4875 Cornwallis) Supermarket Dauan Island (Mt T.S.I.R.C. - Dauan COUNCIL OFFICE, MAIN ST, DAUAN Cornwallis) ISLAND QLD 4875 Doomadgee CEQ – Doomadgee 266 GUNNALUNJA DR, DOOMADGEE QLD Supermarket 4830 Doomadgee Doomadgee 1 GOODEEDAWA RD, DOOMADGEE -

SC2.10 Masig (Yorke) Island Maps

Schedule 2: Mapping SC2.10 Masig (Yorke) Island maps Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 675 This page is intentionally left blank. Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 676 Zenadth Kes Planning Scheme: Planning Scheme for The Torres Strait Island Regional Council Area Saibai Island Ugar LEGEND Island KUKI EXISTING FACILITIES AND INFRASTRUCTURE Airstrip IBIS Store Barge Ramp Sacred Site Cemetery School Child Care Facility Sewerage Infrastructure Erub Church Island Sports Field Community Hall TSIRC Buildings Defence Patrol Depot Telecommunications Electricity Infrastructure Infrastructure Waste Facility ¸Å Fire Station MARUS Water Supply Infrastructure UMI Health Centre EBRINZAR BOUNDARIES AND FEATURES SAU Direction to the nearest Islands BANIUGUB WAK Road Coming of the Light AUPSIRIAM (monument) KOBIN LGA MUR Kuki (NW Winds - January to April) Japanese Burrial Ground Sager (SE Winds - May to December) PATTERN OF LAND USE IDID Lawrences Rd DOPE Township Environmental Management and Conservation Masig 2 Rd Steven Jeff Rd NATURAL ENVIRONMENT KUBUR Lowattas Rd Turtle Barge Ramp Rd Williams Rd FUTURE FACILITIES, INFRASTRUCTURE AND ACTIVITIES MUKUNKUP Dans Rd Aous Rd Township Expansion JDL "Road Town Centre Core " Possible Location for Park and Community Charlies Rd Garden Airstrip Rd Masig" 1 Rd DURI Masig 5 Rd Data Sources: GUDAMADU Unless stated below all landuse, road, or natural feature data shown is from the Strategic Landuse Plan (SLUP) by the RPS Group 2010. Community Consultation 2013: Local Names, Places and identified facilities DARDAR Queensland Dept. Natural Resources and Environment: Imagery, KOD LGA Boundaries, Terrain data and Flooding layers KEKUR AECOM: all strategic framework, zoning and local area plan data is Masig 6 Rd modified from the SLUP and DNRM source data. -

Part 7 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Sea Transport Safety The marine investigation unit of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) was contacted for information pertaining to recent accidents and incidents with large trading vessels in the region. The data provided related to five incidents that occurred after July 1995 and before 2004: a) A man overboard from the vessel Murshidabad in 1996; b) A close quarters situation between the Maersk Taupo and a small dive runabout off Ackers Shoal Beacon in 1997; c) The grounding of the vessel Thebes on Larpent Bank in 1997; d) The grounding of the vessel Dakshineshwar on Larpent Bank in 1997; and e) The grounding of the vessel NOL Amber on Larpent Bank in 1997. Figure 3.7 shows the location of marine accidents that have occurred in northern Queensland in 2004. Figure 3.7 Location of Marine Accidents in Northern Queensland (2004) Source: MSQ: 2005 Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 21 Figure 3.8 Existing Ferry Services Torres Strait Transport Ugar (Stephen) Island Infrastructure Plan Papua New Guinea Ferry Routes ° Saibai (Kaumag) Island Dauan Island Erub (Darnley) Island Map 1 - Saibai (Kaumag) Island to Dauan Island 1:200,000 Map 2 - Ugar (Stephen) Island to Erub (Darnley) Island 1:150,000 Hammond Waiben Map 1 Island (Thursday) Island Map 2 Nguruppai (Horn) Island Muralug (Prince of Wales) Island Map 3 Seisia Seisia Map 3 - Thursday Island 1:300,000 -

1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2

TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY 1997~1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2 ©Commonwealth of Australia 1998 ISSN 1324–163X This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. Annual Report 1997~98 PUPUA NEW GUINEA SAIBAI ISLAND (Kaumag Is) BOIGU ISLAND UGAR (STEPHEN) ISLAND DAUAN ISLAND TORRES STRAIT DARNLEY ISLAND YAM ISLAND MASIG (YORKE) ISLAND MABUIAG ISLAND MER (MURRAY) ISLAND BADU ISLAND PORUMA (COCONUT) ISLAND ST PAULS WARRABER (SUE) ISLAND KUBIN MOA ISLAND HAMMOND ISLAND THURSDAY ISLAND (Port Kennedy, Tamwoy) HORN ISLAND PRINCE OF WALES ISLAND SEISIA BAMAGA CAPE YORK TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY © Commonwealth of Australia 1998 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY Senator the Hon. John Herron Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Suite MF44 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister In accordance with section 144ZB of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Act 1989, I am delighted to present you with the fourth Annual Report of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA).