The Changing Face of Creativity in New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

New York City Scores 2018

New York City Regional Economic Development Council 2018 Annual Report Assessment I. Performance a. Impact on job creation and retention Strengths • For each year from 2011-2016, the unemployment rate in NYC was higher than the unemployment rate in the rest of the state. In 2017, this trend ceased, and the NYC unemployment rate is at an historic low (approximately 4.2 percent) compared to a statewide rate of about 4.6 percent. The veteran unemployment rate followed this same trend. • From 2012-2017 CFA projects (including Priority Projects) are projected to retain 17,620 jobs and created 16,508. • Technology cluster employment increased 46.2 percent from 2011 to 2017 – more than double that of the state increase in tech employment during the same period (21 percent). Weaknesses • From 2016 – 2017, the Advanced Manufacturing cluster had a 3.5 percent decrease in average annual employment (AAE). • From 2016 – 2017, the Life Sciences cluster had a 2.1 percent decrease in AAE, and the Food and Agriculture cluster decreased 0.3 percent. b. Business growth and leverage of private sector investments Strengths • The number of private sector establishments increased 1.8 percent from 2016 to 2017, and 12.1 percent between 2011 and 2017. • Visitor spending increased 33.7 percent between 2011 and 2017. • The Gross Regional Product increased 33.5 percent from 2011 to 2017. • From 2011-2017, the ratio of total project cost to ESD Capital Funds awards was 23.3 to 1. For 2017 the ratio was 9.5. For all CFA projects (including Priority Projects) the ratio was 13.8 to 1. -

Lgbtq-Friendly Youth Organizations in New York City

LGBTQ-FRIENDLY YOUTH ORGANIZATIONS IN NEW YORK CITY A Publication of The Juvenile Justice Coalition, LGBTQ Work Group May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Juvenile Justice Coalition, LGBTQ Work Group thanks Darcy Cues, Legal Intern at The Center for HIV Law and Policy, for her contributions to this resource. Cover art is by Safe Passages Program Youth Leader, Juvenile Justice Project, Correctional Association of New York. For more information on the Juvenile Justice Coalition, LGBTQ Work Group, contact Judy Yu, Chair, at [email protected]. Table of Contents COMMUNITY ORGANIZATIONS ......................................................................................................... 1 ADDICTION SERVICES AND SUPPORT ....................................................................................................... 1 ADVOCACY ORGANIZATIONS ................................................................................................................... 2 RACIAL & ETHNIC ORGANIZATIONS ........................................................................................................ 1 RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS .................................................................................................................. 16 SOCIAL ORGANIZATIONS & ENRICHMENT PROGRAMS .......................................................................... 23 SUPPORT GROUPS, COMMUNITY RESOURCES, & EDUCATION/OUTREACH ........................................... 27 LEGAL ORGANIZATIONS .................................................................................................................. -

Transparency Resolution #2 August 26, 2021 (PDF)

T H E C O U N C I L REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCE RESOLUTION APPROVING THE NEW DESIGNATION AND CHANGES IN THE DESIGNATION OF CERTAIN ORGANIZATIONS TO RECEIVE FUNDING IN THE EXPENSE BUDGET The Committee on Finance, to which the above-captioned resolution was referred, respectfully submits to The Council of the City of New York the following: R E P O R T Introduction. The Council of the City of New York (the “Council”) annually adopts the City’s budget covering expenditures other than for capital projects (the “expense budget”) pursuant to Section 254 of the Charter. On June 19, 2019, the Council adopted the expense budget for fiscal year 2020 with various programs and initiatives (the “Fiscal 2020 Expense Budget”). On June 30, 2020, the Council adopted the expense budget for fiscal year 2021 with various programs and initiatives (the “Fiscal 2021 Expense Budget”). On June 30, 2021, the Council adopted the expense budget for fiscal year 2022 with various programs and initiatives (the “Fiscal 2022 Expense Budget”). Analysis. In an effort to continue to make the budget process more transparent, the Council is providing a list setting forth new designations and/or changes in the designation of certain organizations receiving funding in accordance with the Fiscal 2022 Expense Budget, new designations and/or changes in the designation of certain organizations receiving funding in accordance with the Fiscal 2021 Expense Budget, and amendments to the description for the Description/Scope of Services of certain organizations receiving funding in accordance with the Fiscal 2021, Fiscal 2020 and Fiscal 2019 Expense Budgets. -

Helping Newcomer Students Succeed in Secondary Schools and Beyond Deborah J

Helping Newcomer Students Succeed in Secondary Schools and Beyond Deborah J. Short Beverly A. Boyson Helping Newcomer Students Succeed in Secondary Schools and Beyond DEBORAH J. SHORT & BEVERLY A. BOYSON A Report to Carnegie Corporation of New York Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street NW, Washington, DC 20016 ©2012 by Center for Applied Linguistics All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Center for Applied Linguistics. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.cal.org/help-newcomers-succeed. Requests for permission to reproduce excerpts from this report should be directed to [email protected]. This report was prepared with funding from Carnegie Corporation of New York but does not necessarily represent the opinions or recommendations of the Corporation. Suggested citation: Short, D. J., & Boyson, B. A. (2012). Helping newcomer students succeed in secondary schools and beyond. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. About Carnegie Corporation of New York Carnegie Corporation of New York is a grant-making foundation created by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to do “real and permanent good in this world.” Current priorities in the foundation’s Urban and Higher Education program include upgrading the standards and assessments that guide student learning, improving teaching and ensuring that effective teachers are well deployed in our nation’s schools, and promoting innovative new school and system designs. About the Center for Applied Linguistics The Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving communication through better understanding of language and culture. -

The Son Jarocho Revival: Reinvention and Community Building in a Mexican Music Scene in New York City

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 The Son Jarocho Revival: Reinvention and Community Building in a Mexican Music Scene in New York City Emily J. Williamson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2673 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SON JAROCHO REVIVAL: REINVENTION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING IN A MEXICAN MUSIC SCENE IN NEW YORK CITY by EMILY J. WILLIAMSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 EMILY WILLIAMSON All Rights Reserved ii THE SON JAROCHO REVIVAL: REINVENTION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING IN A MEXICAN MUSIC SCENE IN NEW YORK CITY by EMILY J. WILLIAMSON This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music to satisfy the dissertation Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ ___________________________________ Date Jonathan Shannon Chair of Examining Committee ________________ ___________________________________ Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Peter Manuel Jane Sugarman Alyshia Gálvez THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Son Jarocho Revival: Reinvention and Community Building in a Mexican Music Scene in New York City by Emily J. Williamson Advisor: Peter Manuel This dissertation analyzes the ways son jarocho (the Mexican regional music, dance, and poetic tradition) and the fandango (the son jarocho communitarian musical celebration), have been used as community-building tools among Mexican and non-Mexican musicians in New York City. -

The Italians of the South Village

The Italians of the South Village Report by: Mary Elizabeth Brown, Ph.D. Edited by: Rafaele Fierro, Ph.D. Commissioned by: the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 E. 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 ♦ 212‐475‐9585 ♦ www.gvshp.org Funded by: The J.M. Kaplan Fund Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 212‐475‐9585 212‐475‐9582 Fax www.gvshp.org [email protected] Board of Trustees: Mary Ann Arisman, President Arthur Levin, Vice President Linda Yowell, Vice President Katherine Schoonover, Secretary/Treasurer John Bacon Penelope Bareau Meredith Bergmann Elizabeth Ely Jo Hamilton Thomas Harney Leslie S. Mason Ruth McCoy Florent Morellet Peter Mullan Andrew S. Paul Cynthia Penney Jonathan Russo Judith Stonehill Arbie Thalacker Fred Wistow F. Anthony Zunino III Staff: Andrew Berman, Executive Director Melissa Baldock, Director of Preservation and Research Sheryl Woodruff, Director of Operations Drew Durniak, Director of Administration Kailin Husayko, Program Associate Cover Photo: Marjory Collins photograph, 1943. “Italian‐Americans leaving the church of Our Lady of Pompeii at Bleecker and Carmine Streets, on New Year’s Day.” Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Reproduction Number LC‐USW3‐013065‐E) The Italians of the South Village Report by: Mary Elizabeth Brown, Ph.D. Edited by: Rafaele Fierro, Ph.D. Commissioned by: the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 E. 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 ♦ 212‐475‐9585 ♦ www.gvshp.org Funded by: The J.M. Kaplan Fund Published October, 2007, by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Foreword In the 2000 census, more New York City and State residents listed Italy as their country of ancestry than any other, and more of the estimated 5.3 million Italians who immigrated to the United States over the last two centuries came through New York City than any other port of entry. -

(Former) PUBLIC SCHOOL 64, 605 East 9Th Street (Aka 605-615 East 9Th Street and 350-360 East 10Th Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 20, 2006, Designation List 377 LP-2189 (Former) PUBLIC SCHOOL 64, 605 East 9th Street (aka 605-615 East 9th Street and 350-360 East 10th Street), Manhattan. Built 1904-06, C.B. J. Snyder, architect. Manhattan Tax Map: Block 392, Lot 10. On May 16, 2006, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of (former) Public School 64 (Item No. 4). The hearing was continued to June 6, 2006 (Item No. 1). Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Forty-eight people spoke in favor of designation including City Councilmember Rosie Mendez and representatives of City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, State Assemblymember Sylvia Friedman, Manhattan Borough President Scott M. Stringer, Comptroller William C. Thompson, Jr., Congressmember Nydia Velazquez, State Assemblymember Deborah Glick, State Senator Martin Connor, Community Board Three, the East Village Community Coalition, Place Matters Project, Lower East Side Tenement Museum, Society for the Architecture of the City, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, the Landmarks Conservancy, Municipal Art Society and Historic Districts Council. Six people spoke in opposition to designation including three representatives of the owner, and a representative of REBNY. In addition the Commission has received several hundred letters, petitions and postcards in support of designation. Summary (Former) Public School 64 was designed by master school architect C.B.J. Snyder in the French Renaissance Revival style and built in 1904-06. This was a period of tremendous expansion and construction of new schools due to the consolidation of New York City and its recently centralized school administration, school reforms, and a burgeoning immigrant population. -

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes Associate Professor Department of American Culture, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures Department of Women’s Studies, Latina/o Studies Program University of Michigan, Ann Arbor ADDRESS American Culture, 3700 Haven Hall Ann Arbor, MI (USA) 48109 1 (734) 647-0913 (office) 1 (734) 936-1967 (fax) [email protected] http://larrylafountain.com https://umich.academia.edu/LarryLaFountain EDUCATION Columbia University Ph.D. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1999. New York, NY, USA Dissertation: Culture, Representation, and the Puerto Rican Queer Diaspora. Advisor: Jean Franco. M.Phil. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1996. M.A. Spanish & Portuguese, May 1992. Master’s Thesis: Representación de la mujer incaica en Los comentarios reales del Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Advisor: Flor María Rodríguez Arenas. Harvard College A.B. cum laude in Hispanic Studies, June 1991. Cambridge, MA, USA Senior Honors Thesis: Revolución y utopía en La noche oscura del niño Avilés de Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá. Advisor: Roberto Castillo Sandoval. Universidade de São Paulo Undergraduate courses in Brazilian Literature, June 1988 – Dec. 1989. São Paulo, SP, Brazil AREAS OF INTEREST Puerto Rican, Hispanic Caribbean, and U.S. Latina/o Studies. Queer of Color Studies. Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies. Transnational and Women of Color Feminism. Theater, Performance, and Cultural Studies. Comparative Ethnic Studies. Migration Studies. XXth and XXIth Century Latin American Literature, including Brazil. PUBLICATIONS (ACADEMIC) Books (Single-Authored) 2018 Escenas transcaribeñas: ensayos sobre teatro, performance y cultura. San Juan: Isla Negra Editores, 2018. 296 pages. La Fountain-Stokes CV JUNE 2018 Page 1 La Fountain-Stokes CV JUNE 2018 2 News Coverage - Richard Price and Sally Price, “Bookshelf 2018.” New West Indian Guide, 2019 (forthcoming). -

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 16, 2008, Designation List 405 LP-2263

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 16, 2008, Designation List 405 LP-2263 PUBLIC NATIONAL BANK OF NEW YORK BUILDING (later Public National Bank & Trust Company of New York Building), 106 Avenue C (aka 231 East 7th Street), Manhattan. Built 1923; Eugene Schoen, architect; New York Architectural Terra Cotta Co., terra cotta. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 377, Lot 72. On October 30, 2007, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Public National Bank of New York Building (later Public National Bank & Trust Company of New York Building) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 7). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Five people spoke in favor of designation, including Councilmember Rosie Mendez and representatives of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, Historic Districts Council, Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America, and New York Landmarks Conservancy. The building’s owner opposed designation. In addition, the Commission received a number of communications in support of designation, including letters from City Councilmember Tony Avella, the Friends of Terra Cotta, Neue Galerie Museum for German and Austrian Art, and City Lore: The New York Center for Urban Folk Culture. Summary The Public National Bank of New York Building in the East Village is a highly unusual American structure displaying the direct influence of the early-twentieth- century modernism of eminent Viennese architect/designer Josef Hoffmann. Built in 1923, the bank was designed by Eugene Schoen (1880-1957), an architect born in New York City of Hungarian Jewish descent, who graduated from Columbia University in 1902, and soon after traveled to Europe, meeting Otto Wagner and Hoffmann in Vienna. -

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes Associate Professor Department of American Culture, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures & Department of Women’s Studies Director, Latina/o Studies Program University of Michigan, Ann Arbor ADDRESS American Culture, 3700 Haven Hall Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (734) 647-0913 (office) (734) 936-1967 (fax) [email protected] http://larrylafountain.com EDUCATION Columbia University Ph.D. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1999. Dissertation: Culture, Representation, and the Puerto Rican Queer Diaspora. Advisor: Jean Franco. M.Phil. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1996. M.A. Spanish & Portuguese, May 1992. Master’s Thesis: Representación de la mujer incaica en Los comentarios reales del Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Advisor: Flor María Rodríguez Arenas. Harvard College A.B. cum laude in Hispanic Studies, June 1991. Senior Honors Thesis: Revolución y utopía en La noche oscura del niño Avilés de Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá. Advisor: Roberto Castillo Sandoval. Universidade de São Paulo Undergraduate courses in Brazilian Literature, June 1988 – Dec. 1989. AREAS OF INTEREST Puerto Rican, Hispanic Caribbean, and U.S. Latina/o Studies. Queer of Color Studies. Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies. Transnational and Women of Color Feminism. Theater, Performance, and Cultural Studies. Comparative Ethnic Studies. Migration Studies. XXth and XXIth Century Latin American Literature, including Brazil. PUBLICATIONS (ACADEMIC) Books 2009 Queer Ricans: Cultures and Sexualities in the Diaspora. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. xxvii + 242 pages. La Fountain-Stokes CV October 2013 Page 1 La Fountain-Stokes CV October 2013 2 Reviews - Enmanuel Martínez in CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 24.1 (Fall 2012): 201-04. -

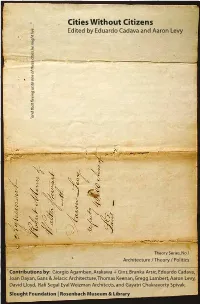

Cities Without Citizens Edited by Eduardo Cadava and Aaron Levy

Cities Without Citizens Edited by Eduardo Cadava and Aaron Levy Contributions by: Giorgio Agamben, Arakawa + Gins, Branka Arsic, Eduardo Cadava, Joan Dayan, Gans & Jelacic Architecture, Thomas Keenan, Gregg Lambert, Aaron Levy, David Lloyd, Rafi Segal Eyal Weizman Architects, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Slought Books, Philadelphia with the Rosenbach Museum & Library Theory Series, No. 1 Copyright © 2003 by Aaron Levy and Eduardo Cadava, Slought Foundation. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or parts thereof, in any form, without written permission from Slought Books, a division of Slought Foundation. No part may be stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. This project was made possible through the Vanguard Group Foundation and the 5-County Arts Fund, a Pennsylvania Partners in the Arts program of the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, a state agency. It is funded by the citizens of Pennsylvania through an annual legislative appropriation, and administered locally by the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance. The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. Additional support for the 5-County Arts Fund is provided by the Delaware River Port Authority and PECO energy. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture, NY for Aaron Levy’s Kloster Indersdorf series, and the International Artists’ Studio Program in Sweden (IASPIS) for Lars Wallsten’s Crimescape series.