Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Wild Animals in Market -Tuensang, Nagaland

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.6 (2):241-253, 2013 Research Article Wildlife exploitation: a market survey in Nagaland, North-eastern India Subramanian Bhupathy1*, Selvaraj Ramesh Kumar1, Palanisamy Thirumalainathan1, Joothi Paramanandham1, and Chang Lemba2 1Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History Anaikatti (Post), Coimbatore- 641 108, Tamil Nadu, India 2C/o Moa Chang, Youth Secretary, Near Chang Baptist, Lashong, Thangnyen, Mission Compound, Tuensang, Nagaland, India *Corresponding Author ([email protected]) Abstract With growing human population, increased accessibility to remote forests and adoption of modern tools, hunting has become a severe global problem, particularly in Nagaland, a Northeast Indian state. While Indian wildlife laws prohibit hunting of virtually all large wild animals, in several parts of North-eastern parts of India that are dominated by indigenous tribal communities, these laws have largely been ineffective due to cultural traditions of hunting for meat, perceived medicinal and ritual value, and the community ownership of the forests. We report the quantity of wild animals sold at Tuensang town of Nagaland, based on weekly samples drawn from May 2009 to April 2010. Interviews were held with vendors on the availability of wild animals in forests belonging to them and methods used for hunting. The tribes of Chang, Yimchunger, Khiemungan, and Sangtam are involved in collection/ hunting and selling of animals in Tuensang. In addition to molluscs and amphibians, 1,870 birds (35 species) and 512 mammals (8 species) were found in the samples. We estimated that annually 13,067 birds and 3,567 mammals were sold in Tuensang market alone, which fetched about Indian Rupees ( ) 18.5 lakhs/ year. -

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Status of Insectivorous Plants in Northeast India

Technical Refereed Contribution Status of insectivorous plants in northeast India Praveen Kumar Verma • Shifting Cultivation Division • Rain Forest Research Institute • Sotai Ali • Deovan • Post Box # 136 • Jorhat 785 001 (Assam) • India • [email protected] Jan Schlauer • Zwischenstr. 11 • 60594 Frankfurt/Main • Germany • [email protected] Krishna Kumar Rawat • CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute • Rana Pratap Marg • Lucknow -226 001 (U.P) • India Krishna Giri • Shifting Cultivation Division • Rain Forest Research Institute • Sotai Ali • Deovan • Post Box #136 • Jorhat 785 001 (Assam) • India Keywords: Biogeography, India, diversity, Red List data. Introduction There are approximately 700 identified species of carnivorous plants placed in 15 genera of nine families of dicotyledonous plants (Albert et al. 1992; Ellison & Gotellli 2001; Fleischmann 2012; Rice 2006) (Table 1). In India, a total of five genera of carnivorous plants are reported with 44 species; viz. Utricularia (38 species), Drosera (3), Nepenthes (1), Pinguicula (1), and Aldrovanda (1) (Santapau & Henry 1976; Anonymous 1988; Singh & Sanjappa 2011; Zaman et al. 2011; Kamble et al. 2012). Inter- estingly, northeastern India is the home of all five insectivorous genera, namely Nepenthes (com- monly known as tropical pitcher plant), Drosera (sundew), Utricularia (bladderwort), Aldrovanda (waterwheel plant), and Pinguicula (butterwort) with a total of 21 species. The area also hosts the “ancestral false carnivorous” plant Plumbago zelayanica, often known as murderous plant. Climate Lowland to mid-altitude areas are characterized by subtropical climate (Table 2) with maximum temperatures and maximum precipitation (monsoon) in summer, i.e., May to September (in some places the highest temperatures are reached already in April), and average temperatures usually not dropping below 0°C in winter. -

UNICEF Support to the COVID-19 Surge in India As Part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A)

UNICEF support to the COVID-19 surge in India as part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) The reach and capacity of the cold chain system in India is strengthened to sustain the massive COVID- 19 vaccine drive • UNICEF has worked at the request of MoHFW to augment the cold chain network across the country since third quarter of 2020. In preparation of the launch of vaccination drive, additional cold chain equipment, such as a Walk-In Cold Rooms (WIC), Walk-In Freezer Rooms (WIF), fridges and deep freezers were procured to enhance vaccine storage at all levels. Vaccine transportation passive devices (cold box/vaccine carriers) were also procured to support the vaccination rollout. • The vaccine rollout was launched nationwide on the 16th of January 2021, with priority to Health Care Workers, Frontline Workers and people aged 60 years and above. On 1st April 2021, vaccination was made available to those above the age of 45. Over 156 million vaccine doses have been administered as of 1st May 2021, Day 106 of the vaccination campaign, making India the country with the fastest vaccination scale up in the world. • As of May 1st, vaccine eligibility has been expanded to all above the age of 18. With this expansion and to support equitable access to vaccination even in remote areas, UNICEF will/ plans to further augment bulk storage sites by providing additional equipment (WIC/WIF) along with Solar Direct Drive (SDD) Fridges for remote locations with limited power supply. • Current COVID-19 vaccines in use in India are freeze sensitive. -

The Adi House: Manifestation of Traditional Wisdom ~~R.N

ARUNACHAL A monthly english journal DECEMBER 2018 1 REVIEW The Adi House: Manifestation of Traditional Wisdom ~~R.N. Koley he Adis, the blanket name fulfillment of the basic needs away from it. Even, every Adi Tof some sub-groups are in- and the requirements of com- village depicts a definite pat- habited in Siang Valley the cen- munity members. Traditions tern in housing. Prospect of tral part of Arunachal Pradesh. and socio-cultural heritage are water, sunlight and drainage They are comprising around uniformly inherited by individu- facility of domestic waste to- one fourth of the tribal popula- als and society. wards lower slope at a village tion of this state. They are hav- The traditional house site are always wisely taken ing unique tradition and rich of the Adis are constructed in consideration with utmost cultural heritage of their own. with bamboos, woods, canes, importance. All these tradi- In Arunachal Pradesh every leaves etc. which are found tional mechanism reveal a ethnic community has own ar- abundant in their surround- foresight and scientific think- chitectural design of house as ings. Till today the construction ing as outcome of deep expe- part of their traditional wisdom is made always on community rience based on century old to cope with their ecology. Like- or collective basis to which all behavioral science. Security of wise the Adis have own tradi- the abled body villagers con- the houses is also major con- tional architect in constructing tribute their labour spontane- cern in early days. In a village their houses which are tested ously as part of century old tra- houses are camouflaged with over the time. -

The Challenge of Peace in Nagaland

India talks with Naga rebels The challenge of peace in Nagaland BY RUPAK CHATTOPADHYAY There are times when the of the most complex. Government of India and armed separatists are not only willing to talk The Nagas before 1975 but to agree on something. That happened on January 31 in Bangkok There are seventeen major and an when both India and one such group, equal number of smaller Naga tribes, the National Socialist Council of each with its own recognizable dialect Nagaland — Isaac Muivah faction, and customs, linked traditionally by a known as NSCN-IM, extended an shared way of life and religious eight-year-old ceasefire for another In New Delhi, the Secretary-General of India's practices, and indeed more recently by six months as both sides attempt to upper house of parliament receives members of Christianity. There are more than 14 find a solution to this long-running the Nagaland Legislative Assembly. tribes that make up the Nagas. Tribal insurgency. conflicts have complicated the process The Naga revolt is centred in the state of Nagaland – one of of peacemaking in the state of seven in North East India. They are known as the “seven Nagaland, and other Naga inhabited areas, over the years. sisters”: Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, Tripura, Meghalaya, Nagas also reside in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram, which are among the Assam and Manipur. most neglected and underdeveloped parts of India. The The Naga rebellion dates back to India’s independence in North East is a remote region connected to the rest of India 1947, when separatist sentiments represented by A. -

National Parks in India (State Wise)

National Parks in India (State Wise) Andaman and Nicobar Islands Rani Jhansi Marine National Park Campbell Bay National Park Galathea National Park Middle Button Island National Park Mount Harriet National Park South Button Island National Park Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park North Button Island National ParkSaddle Peak National Park Andhra Pradesh Papikonda National Park Sri Venkateswara National Park Arunachal Pradesh Mouling National Park Namdapha National Park Assam Dibru-Saikhowa National Park Orang National Park Manas National Park (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Nameri National Park Kaziranga National Park (Famous for Indian Rhinoceros, UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Bihar Valmiki National Park Chhattisgarh Kanger Ghati National Park Guru Ghasidas (Sanjay) National Park Indravati National Park Goa Mollem National Park Gujarat Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch Vansda National Park Blackbuck National Park, Velavadar Gir Forest National Park Haryana WWW.BANKINGSHORTCUTS.COM WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/BANKINGSHORTCUTS 1 National Parks in India (State Wise) Kalesar National Park Sultanpur National Park Himachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Park Khirganga National Park Simbalbara National Park Pin Valley National Park Great Himalayan National Park Jammu and Kashmir Salim Ali National Park Dachigam National Park Hemis National Park Kishtwar National Park Jharkhand Hazaribagh National Park Karnataka Rajiv Gandhi (Rameswaram) National Park Nagarhole National Park Kudremukh National Park Bannerghatta National Park (Bannerghatta Biological Park) -

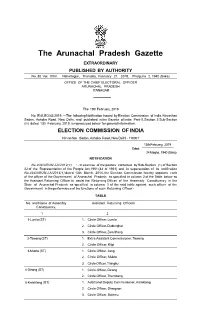

The Arunachal Pradesh Gazette EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY No

The Arunachal Pradesh Gazette EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 80 Vol. XXVI, Naharlagun, Thursday, February 21, 2019, Phalguna 2, 1940 (Saka) OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER ARUNACHAL PRADESH ITANAGAR The 19th February, 2019 No. EN/LEG/43/2019. —The following Notification issued by Election Commission of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi, and published in the Gazette of India Part-II, Section 3 Sub-Section (iii) dated 13th February, 2019, is reproduced below for general information. ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nlrvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhl - 110001 13th February, 2019 Dated : 24 Magha, 1940 (Saka). NOTIFICATION No.434/ARUN-LA/2019(1) : - In exercise of the powers conferred by Sub-Section (1) of Section 22 of the Representation of the People Act,1951 (43 of 1951) and in supersession of its notification No.434/ARUN-LA/2014(1) dated 13th March, 2014, the Election Commission hereby appoints each of the officer of the Govemment of Arunachal Pradesh, as specified in column 2 of the Table below as the Assistant Returning Officer to assist the Returning Officer of the Assembly Constituency in the State of Arunachal Pradesh as specified in column 1 of the said table against such officer of the Government in the performance of the functions of such Returning Officer:- TABLE No. and Name of Assembly Assistant Returning Officers Constituency. 1 2 1-Lumla (ST) 1. Circle Officer, Lumla 2. Circle Officer, Dudunghar 3. Circle Officer, Zemithang 2-Tawang (ST) 1. Extra Assistant Commissioner, Tawang 2. Circle Officer, Kitpi 3-Mukto (ST) 1. Circle Officer, Jang 2. -

Food Security in North-East Region of India — a State-Wise Analysis

Agricultural Economics Research Review Vol. 28 (Conference Number) 2015 pp 259-266 DOI: 10.5958/0974-0279.2015.00041.5 Food Security in North-East Region of India — A State-wise Analysis A. Roy*, N.U. Singh, D.S. Dkhar, A.K. Mohanty, S.B. Singh and A.K. Tripathi ICAR Research Complex for North-Eastern Hill Region, Umiam - 793 103, Meghalaya Abstract With the adoption of high-yielding varieties of paddy, the foodgrains production has increased in North- East region of India. To estimate the growth performance of agriculture, time series data on area, production and productivity of foodgrains have been analysed for the period 1972-73 to 2011-12, which was divided into three decades, viz. 1982-83 to 1991-92 (I decade), 1992-93 to 2001-02 (II decade), 2002-03 to 2011- 12 (III decade) and overall period 1972-73 to 2011-12. During the overall period, among the states, Nagaland registered the highest significant growth in area, production and yield, followed by Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram. All the NE states have shown positive growth rates in area, production and yield increase. The decomposition analysis of growth has suggested that sources of output growth were almost same in all the periods. During the first decade, the major contribution in the change of foodgrain production in the region was of area effect (74.8%), followed by yield effect (22.8%), whereas in all-India, the yield effect was 71 per cent. During the second period, the region had almost half sharer (50.3%) of area effect in food security, followed by yield effect (42.7%). -

Assam & Nagaland

ASSAM & NAGALAND FESTIVALS, TRIBES AND TEA GARDENS HIGHLIGHTS INCLUDE GENERAL SUMMARY Majuli the world’s second largest river island is a further • Tribes of Nagaland We are excited to announce a new and improved itinerary highlight where we visit monks and interact with the • Naga Hornbill Festival for our photographic tour of some remote and little-known friendly local people renowned for their boat skills on the • Majuli, the world’s largest river island areas of North East India. Join us for this epic adventure mighty Brahmaputra. Moving on to Nagaland we explore • The Kaziranga Nature Reserve that takes us to both Assam and the tribal villages of this little known tribal state bordering Myanmar. It com- • Jeep and elephant safaris Nagaland. Assam is better known than its neighbouring prises sixteen regions and numerous ethnically different • Great Indian One Horned Rhino Indian states through its reputation as one of the coun- hill tribes. We will have opportunities to visit some of the • Tea plantations of Assam try’s major tea-growing areas. In Assam our journey starts villages and tribes. We will also spend two nights in • Tranquil heritage tea bungalows with a visit to the Kaziranga National Park, famous for its Touphema Village, home to the Rengma tribe. We con- • Visits to monks and monasteries conservation of the Great Indian One-horned Rhinoceros. clude our Nagaland adventure with two days at the annual • Touphema, Rengma tribal village From here we explore the tea gardens that Assam is fam- Hornbill Festival where many of the remote tribes come • Diverse birdlife ous for. -

District Census Handbook, Tirap, Part XII a & B, Series-3, Arunachal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -3 ARUNACHAL PRADESH PART XII • A & B 7 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWN-WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT TAPAN SENAPATI Director of Census Operations, Arunachal Pradesh .9l.runaclia[ Pradesh is a tftinfy popu{atcd hif[y tract eying rougfdy 6etween tfie Latitutfe3 2(il 28' 'J{ arllf 29° 31' 'J{ ane{ tfie Longitlldes 91° 30' 'E ana 9-;0 30' 'E on tfie !J{prth 'East ettremity of [ne{ia, colllpri.5ing rollgf:~1 of 83,743 ?\jfometre squares of area. It is 60unaet! on tfie 'J{prth, IJ..[prth-'East ana 'J{prtli-'West 6y Cfiina (nEet), on tfie Soutfi oy Jlssam ana 'J{aga{ana, on tfie South-tEast 6y :Myanmar (13urma) ana on tfie Ubt 6y 13hutan. 'The Pradesh is kt;O'll/fl to 6e ricfi in _{(ora, fauna, power anti minera{ potentia[. 'JIjJfien tfie 1971 Census was taK~n in Jlrunacha[ Praacsfi, tfie area was K!wwn as tfie 'J{prth 'East '}"rontier _'4gency (iJ..f.£'}"fl in sfiort) 7uhicfi zuas coHstitutiona[{y a part of tfie state of Jlssam. Jlt tfiat time 'J{'E'}"JI zuas directfy alministered oy tfte Presitfent of Inaia tfirougfi ~he (jovemor of Jlssam as fiis agent, wfio was assisted by an _'4aviser. 'The office of tfie JItfzliser to the (jovcmor of Jlssam 'was situatetf at Sfii[[ong, tfie former capitaC of tfie JIssam S tatc, n0Jt{ tfie Capi taf of i)legha [aya . On 21st January, 1972 iJ..f.E'.Fi.! was gj'lIen tfic status of a 1.1nion 'Territory undcr tlie proz1ision of tfie 'J.{prtfi-'Eastern JIrca ('1\!organisatioH) JIct, 1971 (8 of 1971) and p[aced tlnaer tfie cha.rge of a [fiieJ Commissioner witft ftis fieaaqllarters at Sfii{{ong. -

Protected Areas in News

Protected Areas in News National Parks in News ................................................................Shoolpaneswar................................ (Dhum- khal)................................ Wildlife Sanctuary .................................... 3 ................................................................... 11 About ................................................................................................Point ................................Calimere Wildlife Sanctuary................................ ...................................... 3 ......................................................................................... 11 Kudremukh National Park ................................................................Tiger Reserves................................ in News................................ ....................................................................... 3 ................................................................... 13 Nagarhole National Park ................................................................About................................ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 .................................................................... 14 Rajaji National Park ................................................................................................Pakke tiger reserve................................................................................. 3 ...............................................................................