Retail Globalization and Household Welfare: Evidence from Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW Albertsons/Safeway Case Study

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW Albertsons/Safeway Case Study Fall 2020 Georgetown University Law Center Professor Dale Collins ALBERTSONS/SAFEWAY CASE STUDY Table of Contents The deal Safeway Inc. and AB Albertsons LLC, Press Release, Safeway and Albertsons Announce Definitive Merger Agreement (Mar. 6, 2014) .............. 4 The FTC settlement Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Requires Albertsons and Safeway to Sell 168 Stores as a Condition of Merger (Jan. 27, 2015) .................................... 11 Complaint, In re Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., No. C-4504 (F.T.C. filed Jan. 27, 2015) (challenging Albertsons/Safeway) .................... 13 Agreement Containing Consent Order (Jan. 27, 2015) ................................. 24 Decision and Order (Jan. 27, 2015) (redacted public version) ...................... 32 Order To Maintain Assets (Jan. 27, 2015) (redacted public version) ............ 49 Analysis of Agreement Containing Consent Orders To Aid Public Comment (Nov. 15, 2012) ........................................................... 56 The Washington state settlement Complaint, Washington v. Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., No. 2:15-cv-00147 (W.D. Wash. filed Jan. 30, 2015) ................................... 69 Agreed Motion for Endorsement of Consent Decree (Jan. 30, 2015) ........... 81 [Proposed] Consent Decree (Jan. 30, 2015) ............................................ 84 Exhibit A. FTC Order to Maintain Assets (omitted) ............................. 100 Exhibit B. FTC Order and Decision (omitted) ..................................... -

SWY 2005 Annual Report Final 72.Qxd

SAFEWAY INC. 2005 ANNUAL REPORT Reinventing the Shopping Experience Financial Highlights 52 Weeks 52 Weeks 53 Weeks (Dollars in millions, except per-share amounts) 2005 2004 2003 For the Year: Sales and other revenue $38,416.0 $35,822.9 $35,727.2 Gross profit 11,112.9 10,595.3 10,724.2 Operating profit 1,214.7 1,172.8 573.9 Net income (loss) 561.1 560.2 (169.8) Diluted earnings (loss) per share 1.25 1.25 (0.38) Cash capital expenditures 1,383.5 1,212.5 935.8 At Year End: Common shares outstanding (in millions) (Note 1) 449.4 447.7 444.2 Retail square feet (in millions) 81.0 82.1 82.6 Number of stores 1,775 1,802 1,817 Note 1: Net of 130.7 million, 130.8 million and 131.2 million shares held in treasury in 2005, 2004 and 2003, respectively. About Safeway Safeway Inc. is one of the largest food and drug retailers in North America. As of December 31, 2005, the company operated 1,775 stores in the Western, Southwestern, Rocky Mountain, Midwestern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States and in western Canada. In support of its stores, Safeway has an extensive network of distribution, manufacturing and food processing facilities. Contents Letter to Stockholders 2 Focusing on the Consumer 5 Directors and Principal Officers 16 Safeway at a Glance 18 Annual Report on Form 10-K 19 Investor Information Inside back cover Based on extensive consumer research, we developed a strategy three years ago to fundamentally reinvent our business and better meet our customers’ needs. -

Appendix D - Securities Held by Funds October 18, 2017 Annual Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 October 18, 2017

Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 Appendix D - Securities Held by Funds October 18, 2017 Annual Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 October 18, 2017 Appendix D: Securities Held by Funds The Four Funds hold thousands of publicly and privately traded securities. Act 44 directs the Four Funds to publish “a list of all publicly traded securities held by the public fund.” For consistency in presenting the data, a list of all holdings of the Four Funds is obtained from Pennsylvania Treasury Department. The list includes privately held securities. Some privately held securities lacked certain data fields to facilitate removal from the list. To avoid incomplete removal of privately held securities or erroneous removal of publicly traded securities from the list, the Four Funds have chosen to report all publicly and privately traded securities. The list below presents the securities held by the Four Funds as of June 30, 2017. 1345 AVENUE OF THE A 1 A3 144A AAREAL BANK AG ABRY MEZZANINE PARTNERS LP 1721 N FRONT STREET HOLDINGS AARON'S INC ABRY PARTNERS V LP 1-800-FLOWERS.COM INC AASET 2017-1 TRUST 1A C 144A ABRY PARTNERS VI L P 198 INVERNESS DRIVE WEST ABACUS PROPERTY GROUP ABRY PARTNERS VII L P 1MDB GLOBAL INVESTMENTS L ABAXIS INC ABRY PARTNERS VIII LP REGS ABB CONCISE 6/16 TL ABRY SENIOR EQUITY II LP 1ST SOURCE CORP ABB LTD ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS II LP 200 INVERNESS DRIVE WEST ABBOTT LABORATORIES ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS IV LP 21ST CENTURY FOX AMERICA INC ABBOTT LABORATORIES ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS V LP 21ST CENTURY ONCOLOGY 4/15 -

JOIM 9 4.Pdf

Editor-in-chief: Łukasz Sułkowski Associate editor: Michał Chmielecki Text design and typesetting: Marcin Szadkowski Cover design: Marcin Szadkowski Language editing: Zbigniew Pyszka Adjustment: Dominika Świech Editorial office: Społeczna Akademia Nauk ul. Kilińskiego 109, 90-011 Łódź tel./fax: (42) 664 66 21 e-mail: [email protected] All the articles published in the magazine are subject to reviews. Digital version is the original version of the magazine. © copyright by Społeczna Akademia Nauk ISSN 2543-831X Contents Adam Bednarek 5 Multilingual Families: A Sociolinguistic Model for Retaining Language Ability and Cultural Heritage Iryna Stavytska 21 Modern Tendencies in Foreign Language Teaching Iryna Lytovchenko, Olena Terenko, Olena Ogienko 31 Use of Project-Based Learning of Adults at Corporate Universities in The US and Canada Oksana Chugai 47 Intercultural Competence Formation of ESL Teachers in a Global Educational Environment Maciej Dębski, Adriana Krawczyk 59 Competitiveness of Family Tourist Micro-Enterprises as an Element of Tourist Destination Product Łukasz Haromszeki, Piotr Jarco 77 Educational Leaders and Their Qualities from the Followers’ Perspective Yuliana Lavrysh 97 Transformations in Ukrainian Culture of Learning Beatriz Pérez Sánchez, Marcela Rebeca Contreras Loera 113 Strategies and Structure of the Family Economic Group Casa Ley Mohamed Mousa, Andrew Adjah Sai, Gehad Salhin 141 An Exploration for the Motives behind Enhancing Senior Banker’s Level of Organizational Resilience: A Holistic Case Study Magdalena -

Office of Foreign Assets Control Specially Designated Nationals And

OF FICE OF FOR EIGN AS SETS CON TROL SPE CIALLY DES IG NATED NA TION ALS AND BLOCKED PER SONS March 27, 2002 7TH APRIL CARD BOARD FACTORY, Tajoura, ABD-AL-WAHAB, Abd-al-Hai Ahmad (a.k.a. a.k.a. ATIF, Muhammad; a.k.a. EL KHABIR, Abu Libya [LIBYA] ‘ABD-AL-’IZ; a.k.a. ABU YASIR; a.k.a. ‘ABD Hafs el Masry; a.k.a. TAYSIR); DOB 1951; Alt. 17 NOVEMBER (a.k.a. REVOLUTIONARY ALLAH, ‘Issam ‘Ali Muhammad; a.k.a. AL-KAMEL, DOB 1956; Alt. DOB 1944; POB Alexandria, ORGANIZATION 17 NOVEMBER; a.k.a. Salah ‘Ali; a.k.a. MUSA, Rifa’i Ahmad Taha; a.k.a. Egypt (individual) [SDT] [SDGT] EPANASTATIKI ORGANOSI 17 NOEMVRI) TAHA, Rifa’i Ahmad; a.k.a. TAHA MUSA, Rifa’i ABDULLKADIR, Hussein Mahamud, Florence, [FTO][SDGT] Ahmad; a.k.a. THABIT ‘IZ); DOB 24 Jun 1954; Italy (individual) [SDGT] 32 COUNTY SOVEREIGNTY COMMITTEE (a.k.a. POB Egypt; Passport No. 83860 (Sudan), 30455 ABDULMALIK, Abdul Hameed (a.k.a. MALIK, 32 COUNTY SOVEREIGNTY MOVEMENT; a.k.a. (Egypt), 1046403 (Egypt) (individual) [SDT] Assim Mohammed Rafiq Abdul; a.k.a. RAFIQ, IRISH REPUBLICAN PRISONERS WELFARE ABDALLA, Fazul (a.k.a. MOHAMMED, Fazul Assem), 14 Almotaz Sad Al Deen Street, Al ASSOCIATION; a.k.a. REAL IRA; a.k.a. REAL Abdullah; a.k.a. ADBALLAH, Fazul; a.k.a. AISHA, Nozha, Cairo, Egypt (individual) [IRAQ] IRISH REPUBLICAN ARMY; a.k.a. REAL Abu; a.k.a. AL SUDANI, Abu Seif; a.k.a. ALI, ABDULMOLA, Yousef Abd-El-Razegh (a.k.a. -

Exhibitor Prospectus

EXHIBITOR PROSPECTUS Back to Business... As the global economy reopens over the next several months, retailers will be searching for the product innovations that meet the new, emerging consumer needs brought on by the pandemic. Meet with the top decision-makers from across the industry at The Inspired Home Show 2021. August 7 - 10, 2021 McCormick Place | Chicago, USA TheInspiredHomeShow.com The Industry Event That Matters While trade shows will continue to be a critical 77% of retail buyers use trade channel for introducing retail buyers to your brand shows to discover new brands and and your products, you are likely faced with reduced budgets for travel and exhibitions. This product categories.* means that you have to prioritize the event that is *NuORDER, “State of Retail Buying in 2020” most likely to advance your business in 2021. And that event is The Inspired Home Show. Exhibiting at The Inspired Home Show gives you unparalleled access to retail buyers looking for new home + housewares products and ideas to attract consumers into their stores. Global Opportunity Media Coverage Unique, Focused Buyers The Show attracts the The resulting coverage adds Thousands of buyers who top global key retailers in more than 500 million you won’t see at any other 13 channels and thousands impressions in print, broadcast trade event – and they spend of independent specialty and online placements. significant time and energy buyers from 130 countries. taking full advantage of their time in Chicago. Source: 2019 survey of Show retailer attendees TIME SPENT ON EXPO FLOOR SHOWS BUYERS “NEVER ATTENDED” Average Days Average Total Hours U.S. -

Secretaria De Economía

(Segunda Sección) DIARIO OFICIAL Jueves 30 de agosto de 2012 SECRETARIA DE ECONOMÍA Resolución por la que se acepta la solicitud de parte interesada y se declara el inicio de la investigación antidumping sobre las importaciones de vajillas y piezas sueltas de vajillas de cerámica, incluidas las de porcelana, originarias de la República Popular China, independientemente del país de procedencia. Esta mercancía ingresa por las fracciones arancelarias 6911.10.01 y 6912.00.01 de la Tarifa de la Ley de los Impuestos Generales de Importación y de Exportación. Al margen un sello con el Escudo Nacional, que dice: Estados Unidos Mexicanos.- Secretaría de Economía. RESOLUCIÓN POR LA QUE SE ACEPTA LA SOLICITUD DE PARTE INTERESADA Y SE DECLARA EL INICIO DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN ANTIDUMPING SOBRE LAS IMPORTACIONES DE VAJILLAS Y PIEZAS SUELTAS DE VAJILLAS DE CERÁMICA, INCLUIDAS LAS DE PORCELANA, ORIGINARIAS DE LA REPUBLICA POPULAR CHINA, INDEPENDIENTEMENTE DEL PAÍS DE PROCEDENCIA. ESTA MERCANCÍA INGRESA POR LAS FRACCIONES ARANCELARIAS 6911.10.01 Y 6912.00.01 DE LA TARIFA DE LA LEY DE LOS IMPUESTOS GENERALES DE IMPORTACIÓN Y DE EXPORTACIÓN. Visto para resolver en la etapa inicial el expediente administrativo 06/12 radicado en la Unidad de Prácticas Comerciales Internacionales (UPCI) de la Secretaría de Economía (la “Secretaría”), se emite la presente Resolución de conformidad con los siguientes: RESULTANDOS A. Solicitud 1. El 6 de junio de 2012 Cinsa S.A. de C.V. (“Cinsa” o la “Solicitante”) solicitó el inicio de la investigación administrativa por prácticas desleales de comercio internacional en su modalidad de discriminación de precios en contra de las importaciones de vajillas y piezas sueltas de vajillas de cerámica, incluidas las de porcelana, originarias de la República Popular China (“China”), independientemente del país de procedencia. -

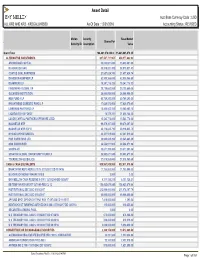

Asset Detail Acct Base Currency Code : USD ALL KR2 and KR3 - KR2GALLKRS00 As of Date : 12/31/2016 Accounting Status : REVISED

Asset Detail Acct Base Currency Code : USD ALL KR2 AND KR3 - KR2GALLKRS00 As Of Date : 12/31/2016 Accounting Status : REVISED Mellon Security Base Market . Shares/Par Security ID Description Value Grand Total 104,481,076,000.8.. 15,445,685,870.25 ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS 637,567,717.951 659,177,482.92 ANCHORAGE CAPITAL 35,653,807.890 35,653,807.89 BLACKROCK GAO 38,510,031.420 38,510,031.42 COATUE QUAL PARTNERS 21,657,624.740 21,657,624.74 DAVIDSON-KEMPNER LP 62,939,366.690 62,939,366.69 DSAM FUND LP 19,247,716.320 19,247,716.32 FINISTERRE GLOBAL OP 25,739,660.080 25,739,660.08 GLENVIEW INSTITUTION 24,044,954.000 24,044,954.00 HBK FUND II LP 60,769,293.000 60,769,293.00 KNIGHTHEAD DOMESTIC FUND L P 17,629,570.450 17,629,570.45 LIBREMAX PARTNERS LP 10,560,503.100 10,560,503.10 LIQUIDALTS H20 FORCE 18,379.231 21,628,144.20 LUXOR CAPITAL PARTNERS OFFSHORE LTDD 15,543,776.000 15,543,776.00 MAGNETAR MTP 99,479,307.000 99,479,307.00 MAGNETAR MTP EOF II 20,116,043.790 20,116,043.79 MYRIAD OPPORTUNITIES 42,247,515.000 42,247,515.00 PINE RIVER FUND LTD 20,045,665.290 20,045,665.29 QMS DIVERSIFIED 24,534,971.960 24,534,971.96 SCOPIA VII 30,817,295.260 30,817,295.26 SENATOR GLOBAL OPPORTUNITY FUND LP 30,993,671.040 30,993,671.04 TOURBILLON GLOBAL EQ 37,018,565.690 37,018,565.69 CASH & CASH EQUIVALENTS 509,961,809.050 502,511,010.56 BANK OF NY REPO REPO 0.710% 01/13/2017 DD 11/14/16 71,185,000.000 71,185,000.00 BLACKROCK MONEY MARKET FD B 3.000 3.00 BNY MELLON CASH RESERVE 0.010% 12/31/2049 DD 06/26/97 6,311,126.210 6,311,126.21 EB TEMP IVN FD VAR -

Barbara Templeton, Et Al. V. Safeway Inc., Et Al. 14-CV-02412-Class

Case4:14-cv-02412-JSW Document1 Filed05/23/14 Page1 of 80 1 FRANCIS M. GREGOREK (144785) [email protected] 2 BETSY C. MANIFOLD (182450) [email protected] 3 RACHELE R. RICKERT (190634) [email protected] 4 MARISA C. LIVESAY (223247) [email protected] 5 WOLF HALDENSTEIN ADLER FREEMAN & HERZ LLP 6 750 B Street, Suite 2770 San Diego, CA 92101 7 Telephone: 619/239-4599 Facsimile: 619/234-4599 8 Attorneys for Plaintiff 9 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 11 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA OAKLAND DIVISION 12 13 BARBARA TEMPLETON, on Behalf of Herself Case No. and All Others Similarly Situated, 14 Plaintiff, CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR 15 v. VIOLATIONS OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT, SELF-DEALING, 16 SAFEWAY INC.; ROBERT L. EDWARDS; T. AND FOR BREACH OF FIDUCIARY GARY ROGERS; WILLIAM Y. TAUSCHER; DUTIES 17 MOHAN GYANI; ARUN SARIN; 18 JANET E. GROVE; FRANK C. HERRINGER; KENNETH W. ODER; GEORGE J. MORROW; 19 AB ACQUISITION LLC; ALBERTSON’S HOLDINGS LLC; 20 ALBERTSON’S LLC; SATURN ACQUISITION MERGER SUB, INC.; and CERBERUS 21 CAPITAL MANAGEMENT L.P., 22 Defendants 23 24 25 26 27 28 CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Case4:14-cv-02412-JSW Document1 Filed05/23/14 Page2 of 80 1 SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 2 1. Plaintiff Barbara Templeton (“Plaintiff”) brings this shareholder class action 3 for herself, and on behalf of all similarly situated holders of Safeway Inc. (“Safeway” or the 4 “Company”) common stock against Safeway, the members of the Company’s Board of Directors 5 (the “Board” or the “Individual Defendants”), AB Acquisition LLC (“AB Acquisition”), 6 Albertson’s Holdings LLC (“Albertson’s Holdings”), Albertson’s LLC (“Albertson’s LLC”), 7 Saturn Acquisition Merger Sub, Inc. -

Annual Report Illinois State Board of Investment

2015 ANNUAL REPORT • ILLINOIS STATE BOARD OF INVESTMENT Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 Board Members 3 Letter to Trustees 8 Financial Highlights 9 Ten Year Summary FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 10 Independent Auditors’ Report 13 Financial Statements 14 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 16 Statements of Net Position 17 Statements of Changes in Net Position 18 Notes to Financial Statements SUPPLEMENTAL FINANCIAL INFORMATION 36 Portfolio of Investments 122 Portfolio Data 124 Investment Transactions with Brokers and Dealers 126 Restricted Investments 128 Staff and Investment Managers Printed on contract by authority of the State of Illinois, December 9, 2015 (100 copies at $25.75 each) ILLINOIS STATE BOARD OF INVESTMENT 1 Board Members Marc Levine Mark Cozzi Justice Mary Seminara-Schostok CHAIRMAN EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Marc Levine Marc Levine Appointed Member Chairman VICE CHAIRMAN Mark Cozzi Mark Cozzi Vice Chairman Appointed Member Justice Mary Seminara-Schostok RECORDING SECRETARY Recording Secretary Justice Mary Seminara-Schostok James F. Clayborne Ezequiel Flores Chairman, Board of Trustees Shari Greco Reiches Judges’ Retirement System of Illinois Member at Large MEMBER-AT-LARGE AUDIT & COMPLIANCE COMMITTEE Shari Greco Reiches Justice Mary Seminara-Schostok, Appointed Member Chairman Senator James F. Clayborne Senator James F. Clayborne Michael W. Frerichs Chairman, Board of Trustees Leslie Geissler Munger General Assembly Retirement System Steven Powell Michael Frerichs INVESTMENT POLICY COMMITTEE Treasurer, State of Illinois Steven Powell, Chairman Michael Frerichs Leslie Geissler Munger Mark Cozzi Leslie Geissler Munger Michael W. Frerichs, Treasurer Comptroller, State of Illinois Shari Greco Reiches Chairman, Board of Trustees Justice Mary Seminara-Schostok State Employees’ Retirement System EMERGING MANAGER COMMITTEE Steven Powell Senator James F. -

State of Illinois State Universities Retirement System

State of Illinois State Universities Retirement System Compliance Examination For the Year Ended June 30, 2017 Performed as Special Assistant Auditors for the Auditor General, State of Illinois State Universities Retirement System of the State of Illinois Compliance Examination For the Year Ended June 30, 2017 Table of Contents Schedule Page(s) State Universities Retirement System Officials 1 Management Assertion Letter 2 Compliance Report Summary 3 Independent Accountant’s Report on State Compliance, on Internal Control Over Compliance, and on Supplementary Information for State Compliance Purposes 5 Independent Auditors’ Report on Internal Control over Financial Reporting and on Compliance and Other Matters Based on an Audit of Financial Statements Performed in Accordance with Government Auditing Standards 9 Schedule of Findings Current Findings – State Compliance 11 Prior Findings Not Repeated 14 Financial Statement Report The System’s financial statement report for the year ended June 30, 2017, which includes the Independent Auditor’s Report, Management Discussion and Analysis, Basic Financial Statements and Notes to the Basic Financial Statements, Required Supplementary Information Other than Management Discussion and Analysis, Supplementary Information, and the Independent Auditor’s Report on Internal Control over Financial Reporting and on Compliance and Other Matters Based on an Audit of Basic Financial Statements performed in accordance with Government Auditing Standards has been issued separately. Supplementary Information for -

SAFEWAY INC. 2003 ANNUAL REPORT Safeway Inc

SAFEWAY INC. 2003 ANNUAL REPORT Safeway Inc. is one of the largest food and drug retailers in North America. As of January 3, 2004, the company operated 1,817 stores in the Western, Southwestern, Rocky Mountain, Midwestern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States and in western Canada. In support of its stores, Safeway has an extensive network of distribution, manufacturing and food processing facilities. PERCENTAGE OF STORES WITH SPECIALTY DEPARTMENTS 2003 1999 Bakery 94% 91% Deli 90 94 Floral 92 89 Pharmacy 74 65 MANUFACTURING AND PROCESSING FACILITIES Year-end 2003 U.S. Canada Milk Plants 63 Bread Baking Plants 62 Ice Cream Plants 22 Cheese and Meat Packaging Plants –2 Soft Drink Bottling Plants 4– Fruit and Vegetable Processing Plants 13 Other Food Processing Plants 2– Pet Food Plant 1– 22 12 CONTENTS 2 Letter to Stockholders 4 Editorial Material 12 Financial Contents 54 Directors and Principal Officers 55 Investor Information FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 53 Weeks 52 Weeks 52 Weeks (Dollars in millions) 2003 2002 2001 FOR THE YEAR Sales $35,552.7 $34,767.5 $34,301.0 Gross profit 10,533.8 10,812.0 10,604.3 Operating profit 573.9 947.6 2,588.8 Net (loss) income (169.8) (828.1) 1,253.9 Diluted (loss) earnings per share: (0.38) (1.77) 2.44 Cash capital expenditures 935.8 1,467.4 1,793.0 AT YEAR END Common shares outstanding (in millions) (Note 1) 444.2 441.0 488.1 Retail square feet (in millions) 82.6 81.5 78.8 Number of stores 1,817 1,808 1,773 Note 1: Net of 131.2 million, 132.0 million and 82.7 million shares held in treasury in 2003, 2002 and 2001, respectively.