A Preliminary Inventory of Alien and Cryptogenic Species in Monastir Bay, Tunisia: Spatial Distribution, Introduction Trends and Pathways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Zurück in Teboulba

Zurück in Teboulba Die zweite Reise zu den tunesischen Fischern Oktober 2010 EineEine Aktion Aktion des des Komitees Komitees SOS SOS Mittelmeer Mittelmeer – – Lebensretter Lebensretter inin NotNot 1 Zurück in Teboulba Euro) im Monat und können die Familie da- von kaum unterstützen. Das Komitee SOS Mittelmeer, das sich 2010 gründete, hat erneut Spenden sammeln Amine Bayoudh, Sohn des verurteilten Kapi- können, um diese zu den tunesischen täns, hat vor drei Jahren eine Ausbildung ab- Fischern nach Teboulba zu bringen. geschlossen. Er ist kein Fischer und war nur Vom 12.-16.10. waren Judith Gleitze und als Ersatzmann an jenem Tage an Bord. Seit Frank Jugert vor Ort, haben mit den Fischern seinem Aufenthalt in Berlin zur Verleihung der gesprochen und ihnen diese zweite Carl-von-Ossietzky Medaille im Dezember Spendensumme übergeben. Die Fischer 2009 lernt er Deutsch an einer Sprachschule richten über uns die herzlichsten Grüße und in Ksar Hellal. Er hat sich im ganzen Land be- Dank an die Unterstützer_innen in worben, findet aber keine Arbeit. Er macht Deutschland aus. sich große Sorgen, dass immer mehr Zeit nach Abschluss seiner Ausbildung ins Land Die derzeitige Situation der sieben Fischer geht und er nicht mehr auf dem neuesten Im November 2009 waren die beiden Kapitä- Stand bleiben kann. Amine hat versucht, über ne Abdelbasseet Zenzeri und Abdelkarim eine in Deutschland lebende Cousine auch Bayoudh verurteilt worden, Migranten nach nach Deutschland zu kommen, um hier zu ar- Italien geschleppt zu haben. Die fünf Fischer, beiten, doch die Bürgschaften und Verpflich- die ebenfalls an Bord der „Morthada“ und der tungserklärungen, die die Cousine auf sich „Mohamed El Hedi“ waren, wurden freige- nehmen müsste, sind zu teuer. -

Arc Chi Ives S P Poin Nss

Département de la Département des Études et Bibliothèque et de la de la Recherche Documention - - Programme Service du Patrimoine « Histoire de Inventaire des Archives l’archéologie française en Afrique du Nord » ARCHIVES POINSSOT (Archives 106) Inventaire au 15 février 2014 - mis à jour le 16/11/2016 (provisoire) FONDS POINSSOT (Archives 106) Dates extrêmes : 1875-2002 Importance matérielle : 206 cartons, 22 mètres-linéaires Lieu de conservation : Bibliothèque de l’INHA (Paris) Producteurs : Julien Poinssot (1844-1900), Louis Poinssot (1879-1967), Claude Poinssot (1928-2002) ; Paul Gauckler (1866-1911), Alfred Merlin (1876-1965), Gabriel Puaux (1883-1970), Bernard Roy (1846-1919). Modalités d'entrée : Achat auprès de Mme Claude Poinssot (2005) Conditions d'accès et d’utilisation : La consultation de ces documents est soumise à l'autorisation de la Bibliothèque de l’INHA. Elle s’effectue sur rendez-vous auprès du service Patrimoine : [email protected]. La reproduction et la diffusion de pièces issues du fonds sont soumises à l’autorisation de l’ayant-droit. Instrument de recherche associé : Base AGORHA (INHA) Présentatin du contenu : Le fonds comprend les papiers de Julien Poinssot (1844-1900), de Louis Poinssot (1879-1967) et de Claude Poinssot (1928- 2002), et couvre une période de plus de 100 ans, des années 1860 au début des années 2000. Il contient des papiers personnels de Julien et Louis Poinssot, les archives provenant des activités professionnelles de Louis et Claude Poinssot, et les archives provenant des travaux de recherche de ces trois chercheurs. Le fonds comprend également les papiers d’autres archéologues et épigraphistes qui ont marqué l'histoire de l'archéologie de l'Afrique du Nord, Paul Gauckler (1866-1911), Bernard Roy (1846-1919) et Alfred Merlin (1876-1965). -

FAO Profil De La Pêche Par Pays

FISHERY COUNTRY PROFILE Food and Agriculture Organization of the United FID/CP/ Nations TUN PROFIL DE LA PÊCHE PAR PAYS Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture Janvier 2005 RESUMENINFORMATIVO SOBRE LA PESCA POR Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la PAISES Agricultura y la Alimentación LA RÉPUBLIQUE TUNISIENNE DONNÉES ÉCONOMIQUES GÉNÉRALES Superficie: 2 163 610 km Superficie du plateau continental (jusqu'à l'isobathe 200 m): 2 80 000 km Longueur des côtes: 1 298 km Population (2003): 9.9 million PIB au prix d'acquisition (2003): 25 billions de $EU PIB par habitant (2003): 2 240 $EU PIB agricole (2003): 12.1 % de PIP DONNÉES SUR LES PÊCHES Bilan des produits (2001): Production Importations Exportations Disponibilités Consommation totales par habitant tonnes (poids vif) kg/année Poisson destiné à la consommation humaine directe 100 350 22 292 15 534 107 117 11.1 Effectifs employés (2003, estimation): secteur primaire: 53 000 personnes secteur secondaire: 47 000 personnes Valeur brute des produits de la pêche 250 millions de $EU (prix payés aux pêcheurs) (2003, estimation): Commerce (2003): valeur des importations: 36.2 millions de $EU valeur des exportations: 105 millions de $EU STRUCTURE ET CARACTERISTIQUES DE L’INDUSTRIE La Tunisie occupe une place centrale dans la Méditerranée. Son littoral dépasse les 1 300 km de long. Son plateau continental est parsemé d'îles et îlots. En effet on rencontre du nord au sud de la Tunisie les îles et îlots suivants : la Galite, le Galiton, Zembra, Zembreta, Kuriat, Kerkennah et Djerba. La superficie du plateau continental est d'environ 80 000 km². -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Patterns and processes of Tunisian migration Findlay, A. M. How to cite: Findlay, A. M. (1980) Patterns and processes of Tunisian migration, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8041/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk PATTERNS AND PROCESSES OP TUNISIAN MIGRATION Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Durham for the Degree of Ph D. Mian M Pindlay M A Department of Geography May 1980 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged 1 ABSTRACT Patterns and processes of post-war Tunisian migration are examined m this thesis from a spatial perspective The concept of 'migration regions' proved particularly interesting -

FIE Filecopy"Y Public Disclosure Authorized

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY FIE FILECOPy"Y Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 2436a-TUN Public Disclosure Authorized STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT OF THE SECOND FISHERIES PROJECT TlJNISIA Public Disclosure Authorized June 6, 1979 Public Disclosure Authorized EMENA Projects Department Agriculture Division II This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Rank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of March 31, 1979) Currency Unit = Tunisian Dinar (D) D 0.4 = US$1.00 D 1.00 = US$2.50 D 1,000,000 - US$2,500,000 US$1,000,000 - D 400,000 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES (Metric System) 1 t = 1,000 kg 2,205 lb 1 km = 0.621 mi 1 km2 = 0.386 sq mi Im = 3.281 ft 1Im2 10.75 sq ft 1 m3 = 35.315 cu ft GOVERNMENT OF TUNISIA Fiscal Year January 1 - December 31 FOR OFFICIALUSE ONLY ABBREVIATIONS BNT Banque Nationale de Tunisie - National Bank of Tunisia CLCM Caisse Locale de Credit Mutuel - Mutual Credit Bank DSP Direction des Services des Peches - Directorate of Fisheries FAO-CP Food and Agriculture OrganizationCooperative Program FOSDA Fonds Special de DeveloppementAgricole - Special Fund for AgriculturalDevelopment FOSEP Fonds Special d'En.couragementa la Peche - Special Fund for Fisheries Development GDP Gross Domestic Product ICB InternationalCompetitive Bidding INSTOP Institut Scientifiqueet Technique d'Oceanographiet de P'eche- Institute c,fScience and Technology for Oceanography and Fisheries ONP Office National des Peches - National Office of Fisheries MSY Maximum SustainableYield HARBORDEPARTMENT Department of Harbors and Aerial Bases in the Ministry of Equipment This documenthas a restricteddistribution and may be used by recipientsonly in the performance of theirofficial duties. -

Le Sahel Tunisien

Le Sahel tunisien Chapitre tiré du guide Extrait de la publication 9782896655762 Le plaisir de mieux voyager P1 LE SAHEL A1 Hergla Si Bou Ali Port El Kantaoui N Kalaa Kebira Akouda Hammam Sousse Kalaa Seghira Sousse A1 Monastir Ksiba Skanès Îles Kuriat Moureddine Sahline Msaken Quardanine M P12 Bembla e Kneis Sayada Lamta Mesdour Ksar Hellal r Bourjine Menzel Teboulba M Kamel Bekalta Moknine é Jemmal d Beni Hassen i Zeramdine t e Si Ben Nour Hiunbo r P1 r Ez Zghana Mahdia a Kerker n Bou Merdas Rejiche é Ksour Essaf e Salakta Alouane Souassi El Bhira Zorda El Jem Ouled Hannachi Bir Bradaa Chorbane Chebba Mellouleche Neffatia La Hencha Bir Tebeug Jebeniana Hazeg La Louza Dokhane El Amra Si Litayem P1 P13 Île Roumedia Sakiet Ezzit Île Chergui Sakiet Eddaïr Île El Aïn Ech Chergui Gremdi Agareb Sfax El Ataya Sidi Fredj Remla P14 Ouled Yaneg Ouled Kacem Sidi Youssef Thyna Melita na ke er Île Gharbi s K P1 Île Nakta Mahares 0 10 20km guidesulysse.com Extrait de la publication Port El Kantaoui Sousse Monastir Mahdia El Jem Îles Kerkena Sfax Le Sahel tunisien Accès et déplacements 4 Activités de plein air 25 Renseignements utiles 6 Hébergement 27 Attraits touristiques 8 Restaurants 36 Port El Kantaoui 8 Sousse 9 Sorties 41 La médina 11 La ville nouvelle 13 Achats 43 Monastir 14 Index 44 Mahdia 16 El Jem 19 Sfax 21 La ville nouvelle 21 La médina 21 Îles Kerkena 23 Extrait de la publication guidesulysse.com ahel (de l’arabe sahil, qui signifie «littoral» ou «bordure»): ce mot évoque, entre autres images, une contrée aux doux rivages, bai S gnée des chauds rayons du soleil. -

RAISON SOCIALE ADRESSE CP VILLE Tél. Fax RESPONSABLES

Secteur RAISON SOCIALE ADRESSE CP VILLE Tél . Fax RESPONSABLES d’Activité 2MB Ing conseil Cité Andalous Immeuble D Appt. 13 5100 Mahdia 73 694 666 BEN OUADA Mustapha : Ing conseil ABAPLAST Industrie Rue de Entrepreneurs Z.I. 2080 Ariana 71 700 62 71 700 141 BEN AMOR Ahmed : Gérant ABC African Bureau Consult Ing conseil Ag. Gafsa: C-5, Imm. B.N.A. 2100 Gafsa 76 226 265 76 226 265 CHEBBI Anis : Gérant Ag. Kasserine: Av Ali Belhaouène 1200 Kasserine 34, Rue Ali Ben Ghédhahem 1001 Tunis 71 338 434 71 350 957 71 240 901 71 355 063 ACC ALI CHELBI CONSULTING Ing conseil 14, Rue d'Autriche Belvédère 1002 Tunis 71 892 794 71 800 030 CHELBI Ali : Consultant ACCUMULATEUR TUNISIEN (L’) Chimie Z.I. de Ben Arous B.P. N° 7 2013 Ben Arous 71 389 380 71 389 380 Département Administratif & ASSAD Ressources Humaines ACHICH MONGI Av 7 Novembre Imm AIDA 2éme Achich Mongi Ingénieur Conseil Etudes et Assistances Technique Ing conseil Etage bloc A N°205 3000 Sfax 74 400 501 74 401 680 [email protected] ACRYLAINE Textile 4, Rue de l'Artisanat - Z.I. Charguia II 2035 Tunis 71 940 720 71 940 920 [email protected] Carthage Advanced e- Technologies Electronique Z.I. Ariana Aéroport – Imm. Maghrebia - 1080 Tunis Cdx 71 940 094 71 941 194 BEN SLIMANE Anis: Personnel Bloc A Boulevard 7 Novembre – BP www.aetech-solutions.com 290 ADWYA Pharmacie G.P. 9 Km 14 - B.P 658 2070 Marsa 71 742 555 BEN SIDHOM R. -

Le Bulletin Archéologique De Sousse

SOCIÉTÉ ARCHÉOLOGIQUE DE SOUSSE STATUTS er ARTICLE 1 — Il est institué à Sousse, sous le nom de Société Archéologique de Sousse, une association dont le but est de grouper toutes les personnes qui s'intéressent à l'histoire du pays, à ses ruines et au développement de la région du Sahel. Cette Société aura pour objectif de faire mieux connaître la région et d'y attirer des visiteurs en aménageant et en protégeant les ruines qui con- tribuent si puissamment à son pittoresque. Dans ce but la Société agira par les moyens suivants : 1- Fonder une Bibliothèque; 2- S'intéresser au développement du Musée municipal par le concours matériel et moral de ses membres, favoriser de toutes ses ressources l'entretien et la conservation des monuments histo- riques, antiques ou arabes, de la Région de Sousse et signaler à l'administration compétente tous les actes de vandalisme qui pour- raient être portés à sa connaissance, grâce à la surveillance vigilante de ses membres ; 3- Publier un Bulletin où il sera brièvement rendu compte des séances, de toutes les découvertes faites dans la région et des événe- ments l'intéressant au point de vue archéologique ; 4- Affecter tous les fonds non employés au Bulletin ou à la correspondance, à l'acquisition d'objets pour le Musée, ou autant que possible à l'exécution d'une fouille poursuivie d'une manière continue dans un des grands monuments de l'antique Hadrumète ou de ses environs ; 5- Organiser : — 4 — (a) Des réunions au Musée ; (b) Des conférences relatives à un sujet archéologique; (c) Des promenades à Sousse et dans les environs immédiats de la ville chaque fois qu'une étude ou une trouvaille intéressante y sera faite; (d) Des visites aux fouilles effectuées dans la région; (e) Des excursions aux ruines si nombreuses et si intéressantes de toute la contrée; 6- Echanger le Bulletin avec celui des autres Sociétés africaines ou archéologiques. -

Distribution, Habitat and Population Densities of the Invasive Species Pinctada Radiata (Molluca: Bivalvia) Along the Northern and Eastern Coasts of Tunisia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286280734 Distribution, habitat and population densities of the invasive species Pinctada radiata (Molluca: Bivalvia) along the Northern and Eastern coasts of Tunisia Article in Cahiers de Biologie Marine · January 2009 CITATIONS READS 22 131 4 authors, including: Sabiha Tlig-Zouari Oum Kalthoum Ben Hassine University of Tunis El Manar University of Tunis El Manar 74 PUBLICATIONS 738 CITATIONS 287 PUBLICATIONS 1,940 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Congress participation View project Naturalists View project All content following this page was uploaded by Oum Kalthoum Ben Hassine on 16 November 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Cah. Biol. Mar. (2009) 50 : 131-142 Distribution, habitat and population densities of the invasive species Pinctada radiata (Molluca: Bivalvia) along the Northern and Eastern coasts of Tunisia Sabiha TLIG-ZOUARI, Lotfi RABAOUI, Ikram IRATHNI and Oum Kalthoum BEN HASSINE Unité de recherche de Biologie, Ecologie et Parasitologie des Organismes Aquatiques. Campus Universitaire, Université Tunis El Manar, Faculté des Sciences de Tunis, Département de Biologie, 2092 Tunis - TUNISIE. Tel / Fax: (00216) 71881939, Mobile: (00216) 98 234 355. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The pearl oyster Pinctada radiata (Leach, 1814) is an alien species introduced to the Mediterranean Sea and recorded in Tunisia many years ago. However, since its record in Tunisian inshore areas, no studies have been carried out about the spread of this invasive mollusc. Thus, the status of this species is still poorly known and there is a knowledge- gap about its distribution and ecology. -

List of Experts and Damage Commissioners Listed on the Register Held by the Tunisian Federation of Insurance Companies

Tunisian Federation of Insurance Companies LIST OF EXPERTS AND DAMAGE COMMISSIONERS LISTED ON THE REGISTER HELD BY THE TUNISIAN FEDERATION OF INSURANCE COMPANIES Registration N° of Phone Name and First Name Speciality(ies) Date or Address Mobile Fax E-Mail Order Number Deregistration Light and Heavy 1 ABID Salem 23/03/1994 Rue de Pologne - Sousse 4000 73 227 298 Goods Motors ALMIA Habib (cessation Light and Heavy 2 23/03/1994 8 rue sans souci - Bizerte 7061 72 432 350 98 673 237 72 436 537 [email protected] of activity) Goods Motors Light and Heavy 109 rue Aziza Othman Big Ville - 3 AYEDI Noureddine 23/03/1994 74 408 852 25 314 637 74 408 478 [email protected] Goods Motors 3000 Sfax 74 408 998 Dead (BADREDDINE 4 Lamjed) B'DIRI BEN ALOUINE Light and Heavy Avenue BOURGUIBA - cité 5 23/03/1994 73 671 529 Ahmed Goods Motors commerciale - Mahdia BEN LARBI CHERIF Light and Heavy 6 23/03/1994 04 rue l'Hôpital - 2000 Bardo 71 220 599 20 335 170 [email protected] Tahar Goods Motors Cité Charaf - Menzel 7 BEL HADJ Mehrez - Fire 23/03/1994 Abderrahmen - Bizerte 7035 - Light and Heavy 02/08/1994 Goods Motors 22/03/2004 Light and Heavy 15 Bis rue Al - Koweït 2éme 8 BELLILI Salah 23/03/1994 71800524 98320948 71800524 Goods Motors étage Tunis 1002 FTUSA 1 10/03/2020 BEN ABDALLAH Light and Heavy 2 rue Tirmidi Cité Soufiane - 2074 9 23/03/1994 71 775 692 22 530 827 [email protected] Abdelhak Goods Motors la Marsa Dead (BEN JAAFER 10 Mohamed) Dead (BEN CHERIFA 11 Mustapha) BEN LAMINE Light and Heavy 10 Bis rue Andalous - Bab Menara 12 23/03/1994 71 563 111 98 320 325 Abderrahmen Goods Motors - Tunis Light and Heavy 25 Avenue des Martyrs - 5050 13 BEN SALAH Lotfi 23/03/1994 73 476 762 98 405 968 73 476 762 [email protected] Goods Motors Moknine - Light and Heavy 69 rue Houcine BOUZAIENE - 1er 14 BEN SLIMEN Ghazi 23/03/1994 71 354 901 98 303 674 71 355 065 [email protected] Goods Motors Etage, Appt. -

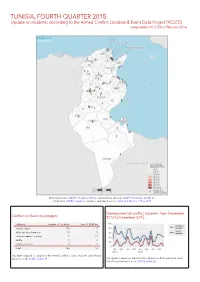

TUNISIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2015: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 4 February 2016

TUNISIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 4 February 2016 National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Development of conflict incidents from December Conflict incidents by category 2013 to December 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities riots/protests 118 3 strategic developments 10 0 violence against civilians 9 17 battle 4 4 remote violence 3 0 total 144 24 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). TUNISIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ben Arous (Tunis Sud), 1 incident killing 0 people was reported. The following location was affected: Ben Arous. In Bizerte, 2 incidents killing 0 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Bizerte, El Azib. In Béja, 1 incident killing 0 people was reported.