In the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heinrich Neuhaus and Alternative Narratives of Selfhood in Soviet Russi

‘I wish for my life’s roses to have fewer thorns’: Heinrich Neuhaus and Alternative Narratives of Selfhood in Soviet Russia Abstract Heinrich Neuhaus (1888—1964) was the Soviet era’s most iconic musicians. Settling in Russia reluctantly he was dismayed by the policies of the Soviet State and unable to engage with contemporary narratives of selfhood in the wake of the Revolution. In creating a new aesthetic territory that defined himself as Russian rather than Soviet Neuhaus embodied an ambiguous territory whereby his views both resonated with and challenged aspects of Soviet- era culture. This article traces how Neuhaus adopted the idea of self-reflective or ‘autobiographical’ art through an interdisciplinary melding of ideas from Boris Pasternak, Alexander Blok and Mikhail Vrubel. In exposing the resulting tension between his understanding of Russian and Soviet selfhood, it nuances our understanding of the cultural identities within this era. Finally, discussing this tension in relation to Neuhaus’s contextualisation of the artistic persona of Dmitri Shostakovich, it contributes to a long- needed reappraisal of his relationship with the composer. I would like to gratefully acknowledge the support of the Guildhall School that enabled me to make a trip to archives in Moscow to undertake research for this article. Dr Maria Razumovskaya Guildhall School of Music & Drama, London Word count: 15,109 Key words: identity, selfhood, Russia, Heinrich Neuhaus, Soviet, poetry Contact email: [email protected] Short biographical statement: Maria Razumovskaya completed her doctoral thesis (Heinrich Neuhaus: Aesthetics and Philosophy of an Interpretation, 2015) as an AHRC doctoral scholar at the Royal College of Music in London. -

STATE SYMPHONIC KAPELLE of MOSCOW (Formerly the Soviet Philharmonic)

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY in association with Manufacturers Bank STATE SYMPHONIC KAPELLE OF MOSCOW (formerly the Soviet Philharmonic) GENNADY ROZHDESTVENSKY Music Director and Conductor VICTORIA POSTNIKOVA, Pianist Saturday Evening, February 8, 1992, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan The University Musical Society is grateful to Manufacturers Bank for a generous grant supporting this evening's concert. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for tickets to upcoming concerts. Twenty-first Concert of the 113th Season 113th Annual Choral Union Series PROGRAM Russian Easter Festival Overture, Op. 36 ......... Rimsky-Korsakov Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 .......... Rachmaninoff Allegro ma non tanto Intermezzo: Adagio Finale: Alia breve Viktoria Postnikova, Pianist INTERMISSION Orchestral Suite No. 3 in G major, Op. 55 .......... Tchaikovsky Elegie Valse melancolique Scherzo Theme and Variations The pre-concert carillon recital was performed by Bram van Leer, U-M Professor of Aerospace Engineering. Viktoria Postnikova plays the Steinway piano available through Hammell Music, Inc. Livonia. The State Symphonic Kapelle is represented by Columbia Artists Management Inc., New York City. Russian Easter Festival Overture, Sheherazade, Op. 35. In his autobiography, My Musical Life, the composer said that these Op. 36 two works, along with the Capriccio espagnoie, NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844-1908) Op. 34, written the previous year, "close a imsky-Korsakov came from a period of my work, at the end of which my family of distinguished military orchestration had attained a considerable and naval figures, so it is not degree of virtuosity and warm sonority with strange that in his youth he de out Wagnerian influence, limiting myself to cided on a career as a naval the normally constituted orchestra used by officer.R Both of his grandmothers, however, Glinka." These three works were, in fact, his were of humble origins, one being a peasant last important strictly orchestral composi and the other a priest's daughter. -

Festival Artists

Festival Artists Cellist OLE AKAHOSHI (Norfolk competitions. Berman has authored two books published by the ’92) performs in North and South Yale University Press: Prokofiev’s Piano Sonatas: A Guide for the Listener America, Asia, and Europe in recitals, and the Performer (2008) and Notes from the Pianist’s Bench (2000; chamber concerts and as a soloist electronically enhanced edition 2017). These books were translated with orchestras such as the Orchestra into several languages. He is also the editor of the critical edition of of St. Luke’s, Symphonisches Orchester Prokofiev’s piano sonatas (Shanghai Music Publishing House, 2011). Berlin and Czech Radio Orchestra. | 27th Season at Norfolk | borisberman.com His performances have been featured on CNN, NPR, BBC, major German ROBERT BLOCKER is radio stations, Korean Broadcasting internationally regarded as a pianist, Station, and WQXR. He has made for his leadership as an advocate for numerous recordings for labels such the arts, and for his extraordinary as Naxos. Akahoshi has collaborated with the Tokyo, Michelangelo, contributions to music education. A and Keller string quartets, Syoko Aki, Sarah Chang, Elmar Oliveira, native of Charleston, South Carolina, Gil Shaham, Lawrence Dutton, Edgar Meyer, Leon Fleisher, he debuted at historic Dock Street Garrick Ohlsson, and André-Michel Schub among many others. Theater (now home to the Spoleto He has performed and taught at festivals in Banff, Norfolk, Aspen, Chamber Music Series). He studied and Korea, and has given master classes most recently at Central under the tutelage of the eminent Conservatory Beijing, Sichuan Conservatory, and Korean National American pianist, Richard Cass, University of Arts. -

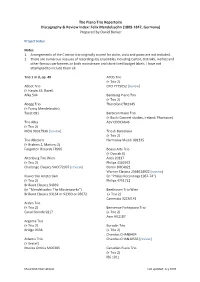

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847, Germany) Prepared by David Barker

The Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847, Germany) Prepared by David Barker Project Index Notes 1. Arrangements of the C minor trio originally scored for violin, viola and piano are not included. 2. There are numerous reissues of recordings by ensembles including Cortot, Oistrakh, Heifetz and other famous performers on both mainstream and short-lived budget labels. I have not attempted to include them all. Trio 1 in d, op. 49 ATOS Trio (+ Trio 2) Abbot Trio CPO 7775052 [review] (+ Haydn 43, Ravel) Afka 544 Bamberg Piano Trio (+ Trio 2) Abegg Trio Thorofon CTH2345 (+ Fanny Mendelssohn) Tacet 091 Barbican Piano Trio (+ Bush: Concert studies, Ireland: Phantasie) Trio Alba ASV CDDCA646 (+ Trio 2) MDG 90317936 [review] Trio di Barcelona (+ Trio 2) Trio Albeneri Harmonia Mundi 901335 (+ Brahms 2, Martinu 2) Forgotten Records FR995 Beaux Arts Trio (+ Dvorak 4) Altenburg Trio Wien Ades 20337 (+ Trio 2) Philips 4162972 Challenge Classics SACC72097 [review] Doron DRC4021 Warner Classics 2564614922 [review] Klaviertrio Amsterdam (in “Philips Recordings 1967-74”) (+ Trio 2) Philips 4751712 Brilliant Classics 94039 (in “Mendelssohn: The Masterworks”) Beethoven Trio Wien Brilliant Classics 93164 or 92393 or 93672 (+ Trio 2) Camerata 32CM141 Arden Trio (+ Trio 2) Benvenue Fortepiano Trio Canal Grande 9217 (+ Trio 2) Avie AV2187 Argenta Trio (+ Trio 2) Borodin Trio Bridge 9338 (+ Trio 2) Chandos CHAN8404 Atlantis Trio Chandos CHAN10535 [review] (+ Sextet) Musica Omnia MO0205 Canadian Piano Trio (+ Trio 2) IBS 1011 MusicWeb International Last updated: July 2020 Piano Trios: Mendelssohn Profil PH08027 Trio Carlo Van Neste (+ Trio 2) Florestan Trio Pavane ADW7572 (+ Trio 2) Hyperion CDA67485 [review] Ceresio Trio (+ Trio 2, Viola trio) Trio Fontenay Doron 3060 (+ Trio 2) Teldec 44947 Chung Trio (in “Mendelssohn Edition Vol. -

Frédéric Chopin, Sviatoslav Richter, Martha Argerich, Mstislav

Frédéric Chopin Sonate Op.65, Polonaise Brillante, Ballades no. 3 & no. 4 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Sonate Op.65, Polonaise Brillante, Ballades no. 3 & no. 4 Country: Germany Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1401 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1220 mb WMA version RAR size: 1211 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 864 Other Formats: MMF TTA MP4 AC3 AU AAC DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Sonata For Piano And Violoncello In G Minor, Op. 65 Piano – Martha ArgerichVioloncello – Mstislav Rostropovich 1 Allegro Moderato 15:15 2 Scherzo. Allegro Con Brio 4:50 3 Largo 3:41 4 Finale. Allegro 5:27 5 Polonaise Brillante In C Major, Op.3 8:09 Ballade No. 3 In A Flat Major, Op. 47 6 7:15 Piano – Sviatoslav Richter 7 Ballade No. 4 In F Minor, Op. 52 11:25 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 028943158329 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Frédéric Chopin / Martha Argerich, Mstislav Frédéric Chopin / Rostropovich, Svjatoslav Martha Argerich, Richter* - Cellosonate Deutsche 431 583-2 Mstislav 431 583-2 US 1991 Op.65 • Polonaise Grammophon Rostropovich, Brillante • Balladen Svjatoslav Richter* Op.47 & Op.52 (CD, Album) Related Music albums to Sonate Op.65, Polonaise Brillante, Ballades no. 3 & no. 4 by Frédéric Chopin Moscow Radio Orchestra With Mstislav Rostropovich And Sviatoslav Richter - Saint-Saens Cello Concerto Op.33, Prokofiev Cello Sonata Op.119 Various - The Originals - Highlights Argerich • Rostropovitch - Schumann • Chopin - National Symphony Orchestra Of Washington - Klavierkonzert Beethoven - Mstislav Rostropovich ‧ Sviatoslav Richter - The Complete Sonatas For Piano And Cello L.v. -

Pogorelich at the Chopin

Edinburgh Research Explorer Pogorelich at the Chopin Citation for published version: Mccormick, L 2018, 'Pogorelich at the Chopin: Towards a sociology of competition scandals', The Chopin Review, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1-16. <http://chopinreview.com/pages/issue/7> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: The Chopin Review General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 CHOPIN Issue 1 THE REVIEW About For Authors Chopin Study Competition Authors Contact Pogorelich at the Chopin: Towards a sociology of Contents competition scandals INTRODUCTION ARTICLES Lisa McCormick Anna Chęćka The competition as an ‘exchange’ of values: An aesthetic and existential perspective ABSTRACT Wojciech Kocyan The evolution of performance style Controversies are a regular feature on the international classical music competition circuit, and some of these explode into scandals in the history of the International Fryderyk Chopin that are remembered long afterward. This essay draws from the sociology of scandal to identify the conditions that predispose classical music competitions to moral disruption and to examine the cultural process through which a scandal attains legendary status. -

Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt & Tchaikovsky

SSIANPIANOTR THE ITIONTHERUSS IGUMNOV SCHOOL USIANPIANOTR ADITIONTHERU SSIANPIANOTRLev ADITIONTHERUOborin ERUSSIANPIANBEETHOVEN OTRADITIONTHEcossaises ERUSSIANPIANSonata in A, Op 2 No 2 CHOPIN IANPIANOTRADÉtudes, Op 25 Nos 2, 3 & 5 ITIONTHERUSSMazurka, Op 50 No 1 IANPIANOTRADSonata No 3, Op 58 LISZT OTRADITIONTHHungarian Rhapsody No 2 ERUSSIANPIANTCHAIKOVSKY RADITIONTHEU 3 pieces from ‘The Months’, Op 37b SSIANPIANOTR ADITIONTHERU SSIANPIANOTR Lev Nikolayevich Oborin (11 November 190 7– 5 January 1974) EV OBORIN was born in Moscow and Polish contestants. Overnight, Oborin became entered that city’s Gnesin Music School in the foremost Soviet pianist of his generation. L1914 where he studied composition with On his triumphant return to Moscow he became Alexander Gretchaninov and piano with Yelena Igumnov’s assistant at the Conservatoire, Gnesina. A pupil of Ferruccio Busoni, Gnesina simul taneously teaching chamber music, a was known for her ‘progressive’ methods, in genre to which he was much drawn – as would particular her emphasis upon musicianship become abundantly evident in his future part - as opposed to repetitive exercises, which she ner ships with the violinists Dmitri Tziganov pursued by insisting pupils should frequently and, from 1935, David Oistrakh. (In 1941 perform concerts and recitals from memory. In Oistrakh and Oborin formed an internationally 1921, the fourteen-year-old Oborin moved on to respected trio with the cellist Sviatoslav the Moscow Conservatoire, joining the piano Knushevitsky which ceased only with the death class of the celebrated pedagogue Konstantin of the latter in 1963.) When Igumnov died in Igumnov and furthering his compositional 1948, Oborin was his natural successor having studies with Georgi Catoire, Georgi Conus by then acquired a reputation as a sympathetic and Nikolai Myaskovsky. -

Soviet Music in the International Arena, 1932–41

02_EHQ 31/2 articles 26/2/01 12:57 pm Page 231 Caroline Brooke Soviet Music in the International Arena, 1932–41 Soviet musical life underwent radical transformation in the 1930s as the Communist Party of the Soviet Union began to play an active role in shaping artistic affairs. The year 1932 saw the dis- banding of militant factional organizations such as the RAPM (Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians) which had sprung up on the ‘musical front’ during the 1920s and had come to dominate Soviet musical life during the period of the first Five Year Plan (1928–32). 1932 was also the year that saw the con- solidation of all members of the musical profession into centralized Unions of Soviet Composers. Despite such compre- hensive administrative restructuring, however, it would be a mis- take to regard the 1930s as an era of steadily increasing political control over Soviet music. This was a period of considerable diversity in Soviet musical life, and insofar as a coherent Party line on music existed at all at this time, it lacked consistency on a great many issues. One of the principal reasons for the contra- dictory nature of Soviet music policy in the 1930s was the fact that the conflicting demands of ideological prejudice and politi- cal pragmatism frequently could not be reconciled. This can be illustrated particularly clearly through a consideration of the interactions between music and the realm of foreign affairs. Soviet foreign policy in the musical sphere tended to hover between two stools. Suspicion of the bourgeois capitalist West, together with the conviction that Western culture was going through the final stages of degeneration, fuelled the arguments of those who wanted to keep Soviet music and musical life pure and uncontaminated by such Western pollutants as atonalism, neo- classicism and the more innovative forms of jazz. -

The Artist Teaching of Alexander Goldenweiser: Fingers in Service to Music Junwei Xue © 2018

The Artist Teaching of Alexander Goldenweiser: Fingers in Service to Music Junwei Xue © 2018 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chair: Steven Spooner Jack Winerock Michael Kirkendoll Ketty Wong Robert Ward Date Defended: 10 May 2018 The dissertation committee for Junwei Xue certifies that this is the approved version of the following doctoral document: The Artist Teaching of Alexander Goldenweiser: Fingering in Service to Music Chair: Steven Spooner Date Approved: 10 May 2018 ii Abstract This paper examines the life, teaching methods, and critical editions of Alexander Goldenweiser (1875-1961), a major figure of the Russian music scene in the first half of the twentieth century. A pianist, teacher, and composer, Goldenweiser left an important legacy with his teaching philosophy and editions of piano scores. Many of his students have become renowned pianists and teachers themselves, who have transmitted Goldenweiser’s teaching philosophy to their own pupils, thus strengthening the widely recognized Russian school of piano. An examination of his teaching methods reveals his teaching philosophy, which focuses on the development of a piano technique that seeks a faithful interpretation of the music scores. In his view, children should start taking piano lessons at an early age to acquire the necessary skills to master all sorts of passages in the piano literature, and to these purposes, he was influential in the creation of the Central Music School in Moscow, where musically-gifted children study the elementary and secondary school levels. -

Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture by Tony Hsiu Lin a Disserta

Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture By Tony Hsiu Lin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anne Nesbet, Co-Chair Professor David Frick, Co-Chair Professor Robert P. Hughes Professor James Davies Spring 2014 Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture © 2014 by Tony Hsiu Lin Abstract Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture by Tony Hsiu Lin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Anne Nesbet, Co-Chair Professor David Frick, Co-Chair Fryderyk Chopin’s fame today is too often taken for granted. Chopin lived in a time when Poland did not exist politically, and the history of his reception must take into consideration the role played by Poland’s occupying powers. Prior to 1918, and arguably thereafter as well, Poles saw Chopin as central to their “imagined community.” They endowed national meaning to Chopin and his music, but the tendency to glorify the composer was in a constant state of negotiation with the political circumstances of the time. This dissertation investigates the history of Chopin’s reception by focusing on several events that would prove essential to preserving and propagating his legacy. Chapter 1 outlines the indispensable role some Russians played in memorializing Chopin, epitomized by Milii Balakirev’s initiative to erect a monument in Chopin’s birthplace Żelazowa Wola in 1894. -

Cultural Importance of the 4Th International Chopin Piano Competition in the Light of Polish Music Life Reviving After the WW II

UNIWERSYTET HUMANISTYCZNO-PRZYRODNICZY IM. JANA DŁUGOSZA W CZĘSTOCHOWIE Edukacja Muzyczna 2020, nr XV http://dx.doi.org/10.16926/em.2020.15.08 Aleksandra POPIOŁEK-WALICKI https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6936-4721 University of Wrocław (Poland) e-mail: [email protected] Cultural Importance of the 4th International Chopin Piano Competition in the Light of Polish Music Life Reviving after the WW II Translation of the published in this issue (http://doi.org/10.16926/em.2020.15.07) How to cite: Aleksandra Popiołek-Walicki, Cultural importance of the 4th International Chopin Piano Competition in the light of Polish music life reviving after the WW II, “Edukacja Muzyczna” 2020, no. 15, pp. 327–345. Abstract The article aims at summarizing different activities undertaken to organize and run the first post- war Chopin piano competition. It is an attempt to collect facts, accounts and memories concerning actions initiated by Polish music culture environment after the Second World War. The author focuses on a detailed description of the organization and proceedings of the 4th International Piano Competi- tion, making use of information that has existed in independent sources so far. The article uses diaries, biographies, autobiographies, private notes, interviews with representatives of Polish culture, archive films and documentaries belonging to the Polish Film Chronicle. Press excepts were not used on pur- pose, as most press information was included in the aforesaid bibliography entries. The analyzed sources let us conclude that the organization of the first post-was Chopin piano competition in Warsaw was an event requiring both the engagement of all state institutions and personal contribution of mu- sicians and music teachers. -

School of Music 2001–2002

School of Music 2001–2002 bulletin of yale university Series 97 Number 4 July 10, 2001 Bulletin of Yale University Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut Issued sixteen times a year: one time a year in May, October, and November; two times a year in June and September; three times a year in July; six times a year in August Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Editor: David J. Baker Editorial and Publishing Office: 175 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, Connecticut Publication number (usps 078-500) The closing date for material in this bulletin was June 10, 2001. The University reserves the right to withdraw or modify the courses of instruction or to change the instructors at any time. ©2001 by Yale University. All rights reserved. The material in this bulletin may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form, whether in print or electronic media, without written permission from Yale University. Inquiries Requests for bulletins and application material should be addressed to the Admissions Office, Yale School of Music, PO Box 208246, New Haven ct 06520-8246. School of Music 2001–2002 bulletin of yale university Series 97 Number 4 July 10, 2001 c yale university ce Pla Lake 102-8 Payne 90-6 Whitney — Gym south Ray York Square Place Tompkins New House Residence rkway er Pa Hall A Tow sh m u n S Central tree Whalley Avenue Ezra Power Stiles t Morse Plant north The Yale Bookstore > Elm Street Hall of Graduate Studies Mory’s Sterling St.