Profile of Pre-Primary Provision in Abidjan and Bouaké

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C O M M U N I Q

MINISTERE DE LA CONSTRUCTION, DU LOGEMENT REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT ET DE L'URBANISME Union - Discipline - Travail LE MINISTRE Abidjan, le N ________/MCLAU/CAB/bfe C O M M U N I Q U E Le Ministre de la Construction, de l’Assainissement et de l’Urbanisme a le plaisir d’informer les usagers demandeurs d’arrêté de concession définitive, dont les noms sont mentionnés ci-dessous que les actes demandés ont été signés et transmis à la Conservation Foncière. Les intéressés sont priés de se rendre à la Conservation Foncière concernée en vue du paiement du prix d'aliénation du terrain ainsi que des droits et taxes y afférents. Cinq jours après le règlement du prix d'aliénation suivi de la publication de votre acte au livre foncier, vous vous présenterez pour son retrait au service du Guichet Unique du Foncier et de l'Habitat. -

Agricultural Microcredit in Cote D'ivoire

DOTTORATO IN SCIENZE ECONOMICHE, AZIENDALI E STATISTICHE DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE ECONOMICHE, AZIENDALI E STATISTICHE SECS-P/06 AGRICULTURAL MICROCREDIT IN COTE D’IVOIRE IL DOTTORE IL DECANO DEL COLLEGIO MOUSTAPHA SANGARE Chiar.mo Prof. FABIO MAZZOLA IL TUTOR Chiar.mo Prof. VINCENZO PROVENZANO CICLO XXIX ANNO CONSEGUIMENTO TITOLO 2017 ! ABSTRACT The financing of agriculture in rural areas for poverty reduction remains an important concern that has involved several research. The granting of microcredit to people with low income is viewed as an opportunity to increase farm income in rural areas. The survey led in Côte d’Ivoire in the region of Tchologo attempted to shed light on the relation between microfinance institution and farmers. This region has about 65% of poverty rate and people are mainly involved in the production of cash and food crops. Through financial diaries methodology, farm needs were tracked to know how farmers manage his little financial resources by the identification of main farm needs and their difficulties to meet them. Indeed, the survey takes into account 202 respondents with farm as main profile among which 34% are credit beneficiaries of UNACOOPEC-Ferké institution. The analysis of the economic and social characteristics provides various information regarding the consideration that grants microfinance institution to farmers. Besides that, the statistical significance (t-test) allowed to dress the concern of the improving of farm income through microcredit supplying. ! ACRONYM ANADER Agence Nationale d’Appui au -

Liste Des Centres De Collecte Du District D'abidjan

LISTE DES CENTRES DE COLLECTE DU DISTRICT D’ABIDJAN Région : LAGUNES Centre de Coordination: ABIDJAN Nombre total de Centres de collecte : 774 ABIDJAN 01 ABOBO Nombre de Centres de collecte : 155 CODE CENTRE DE COLLECTE 001 EPV CATHOLIQUE ST GASPARD BERT 002 EPV FEBLEZY 003 GROUPE SCOLAIRE LE PROVENCIAL ABOBO 004 COLLEGE PRIVE DJESSOU 006 COLLEGE COULIBALY SANDENI 008 G.S. ANONKOUA KOUTE I 009 GROUPE SCOLAIRE MATHIEU 010 E-PP AHEKA 011 EPV ABRAHAM AYEBY 012 EPV SAHOUA 013 GROUPE SCOLAIRE EBENEZER 015 GROUPE SCOLAIRE 1-2-3-4-5 BAD 016 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINT MOISE 017 EPP AGNISSANKO III 018 EPV DIALOGUE ET DESTIN 2 019 EPV KAUNAN I 020 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABRAHAM AYEBY 021 EPP GENDARMERIE 022 GROUPE SAINTE FOI ABIDJAN 023 G. S. LES AMAZONES 024 EPV AMAZONES 025 EPP PALMERAIE 026 EPV DIALOGUE 1 028 INSTITUT LES PREMICES 030 COLLEGE GRACE DIVINE 031 GROUPE SCOLAIRE RAIL 4 BAD B ET C 032 EPV DIE MORY 033 EPP SAGBE I (BOKABO) 034 EPP ATCHRO 035 EPV ANOUANZE 036 EPV SAINT PAUL 037 EPP N'SINMON 039 COLLEGE H TAZIEFE 040 EPV LESANGES-NOIRS 041 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ASSAMOI 045 COLLEGE ANADOR 046 EPV LA PROVIDENCE 047 EPV BEUGRE 048 GROUPE SCOLAIRE HOUANTOUE 049 EPV SAINT-CYR 050 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINTE JEANNE 051 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINTE ELISABETH 052 EPP PLATEAU-DOKUI BAD 054 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABOBOTE ANNEXE 055 GROUPE SCOLAIRE FENDJE 056 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABOBOTE 057 EPV CATHOLIQUE SAINT AUGUSTIN 058 GROUPE SCOLAIRE LES ORCHIDEES 059 CENTRE D'EDUCATION PRESCOLAIRE 060 EPV REUSSITE 061 EPP GISCARD D'ESTAING 062 EPP LES FLAMBOYANTS 063 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ASSEMBLEE -

Interrupting Seasonal Transmission of Schistosoma Haematobium and Control of Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis in Northern and Cent

Tian-Bi et al. BMC Public Health (2018) 18:186 DOI 10.1186/s12889-018-5044-2 STUDYPROTOCOL Open Access Interrupting seasonal transmission of Schistosoma haematobium and control of soil-transmitted helminthiasis in northern and central Côte d’Ivoire: a SCORE study protocol Yves-Nathan T. Tian-Bi1,2*, Mamadou Ouattara1,2, Stefanie Knopp3,4, Jean T. Coulibaly1,2,3,4, Eveline Hürlimann3,4, Bonnie Webster5, Fiona Allan5, David Rollinson5, Aboulaye Meïté6, Nana R. Diakité1,2, Cyrille K. Konan1,2, Eliézer K. N’Goran1,2 and Jürg Utzinger3,4* Abstract Background: To achieve a world free of schistosomiasis, the objective is to scale up control and elimination efforts in all endemic countries. Where interruption of transmission is considered feasible, countries are encouraged to implement a comprehensive intervention package, including preventive chemotherapy, information, education and communication (IEC), water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), and snail control. In northern and central Côte d’Ivoire, transmission of Schistosoma haematobium is seasonal and elimination might be achieved. In a cluster-randomised trial, we will assess different treatment schemes to interrupt S. haematobium transmission and control soil-transmitted helminthiasis over a 3-year period. We will compare the impact of (i) arm A: annual mass drug administration (MDA) with praziquantel and albendazole before the peak schistosomiasis transmission season; (ii) arm B: annual MDA after the peak schistosomiasis transmission season; (iii) arm C: two yearly treatments before and after peak schistosomiasis transmission; and (iv) arm D: annual MDA before peak schistosomiasis transmission, coupled with chemical snail control using niclosamide. Methods/design: The prevalence and intensity of S. -

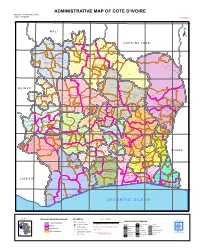

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Ivory Coast Strategy Action Plan

International Rescue Committee Côte d’Ivoire: Strategy Action Plan A Wade A IRC / Revised June 2019 JSoha / IRC / IRC2020 GLOBAL STRATEGY OVERVIEW The International Rescue Committee’s (IRC) mission is to help the world’s most vulnerable people survive, recover, and gain control of their future. The aim of the global strategy, IRC2020 (see right), is to make measurable improvements in health, safety, education, economic wellbeing, and decision-making power. Therefore, the IRC will make investments to have more effective programs, use resources more efficiently, reach more people more quickly and better respond to beneficiaries’ needs. THE IRC IN CÔTE D’IVOIRE: STRATEGY ACTION PLAN 2 CÔTE D’IVOIRE OVERVIEW Civil war in 2002 left Côte d’Ivoire in a fragile socio- mismanagement often forces patients to pay for economic situation, which was further compounded services to which they are entitled. These financial by the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. Today, social barriers to services disproportionately impact services are often of poor quality and limited women and children, who usually do not have availability, which augments growing inequality and control over household expenditures. jeopardizes the country’s return to long term stability. As a result, a large part of the population is uneducated, in poor health, vulnerable to violence Despite strong economic growth in recent years, or exploitation, and with limited economic many populations are still at risk. Rural opportunities. communities and women and girls are often deprived of healthcare and education, and have a The IRC’s strategy for Côte d’Ivoire illustrates its lower quality of life. In addition, women and girls are commitment to improving the health, safety, highly vulnerable to gender-based violence. -

Response to Reviewer's Comments

Response to Reviewer’s comments 1) Section 3.3: There is a diesel exhaust study included in the table of studies in African cities – I do not think that these measurements should be compared in a table of ambient air concentrations – it is important but would be more correctly grouped with emission sou rce concentrations. Therefore I would remove the discussion of this paper in the text and from the Table. This comment is relevant. - 3 - 3 - 3 H ourly average concentrations of SO 2 (18308 µg.m - 214514 µg.m ) and NO 2 (184266.2 µg.m - 597925.3 µg.m - 3 ) were measured at the exhaust of diesel engine in Angola (Amadio et al., 2010) and are reported in our paper . We agree with referee #1 that these values are not representative of ambient air concentrations. Also as proposed, we have removed all references to these measures from the text in Section 3.3 Page 13 , line 1 6 - 1 7 , from the Figure 14 and 15 and from the s upplementary Tables TS3 and TS4. 2) Section 2.2.2: The authors now do an excellent comparison of the NO2 and HNO3 measurements and demonstrate clearly little interference in the passive measurements. It would be worth mentioning the other NO y species including HONO (which can deposit as nitrite which oxidises over to nitrate) To answer to this comment, w e decided to add the following sentence in section 2.2.2 page 5 , line 1 3 - 1 5 . “ Other NOy species such as Peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN) and nitrous acid (HONO) which can deposit as nitrite and oxidize to nitrate may interfere with the determination of NO 2 and HNO 3 concentration (Cape, 2003). -

See Full Prospectus

G20 COMPACT WITHAFRICA CÔTE D’IVOIRE Investment Opportunities G20 Compact with Africa 8°W To 7°W 6°W 5°W 4°W 3°W Bamako To MALI Sikasso CÔTE D'IVOIRE COUNTRY CONTEXT Tengrel BURKINA To Bobo Dioulasso FASO To Kampti Minignan Folon CITIES AND TOWNS 10°N é 10°N Bagoué o g DISTRICT CAPITALS a SAVANES B DENGUÉLÉ To REGION CAPITALS Batie Odienné Boundiali Ferkessedougou NATIONAL CAPITAL Korhogo K RIVERS Kabadougou o —growth m Macroeconomic stability B Poro Tchologo Bouna To o o u é MAIN ROADS Beyla To c Bounkani Bole n RAILROADS a 9°N l 9°N averaging 9% over past five years, low B a m DISTRICT BOUNDARIES a d n ZANZAN S a AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT and stable inflation, contained fiscal a B N GUINEA s Hambol s WOROBA BOUNDARIES z a i n Worodougou d M r a Dabakala Bafing a Bere REGION BOUNDARIES r deficit; sustainable debt Touba a o u VALLEE DU BANDAMA é INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES Séguéla Mankono Katiola Bondoukou 8°N 8°N Gontougo To To Tanda Wenchi Nzerekore Biankouma Béoumi Bouaké Tonkpi Lac de Gbêke Business friendly investment Mont Nimba Haut-Sassandra Kossou Sakassou M'Bahiakro (1,752 m) Man Vavoua Zuenoula Iffou MONTAGNES To Danane SASSANDRA- Sunyani Guemon Tiebissou Belier Agnibilékrou climate—sustained progress over the MARAHOUE Bocanda LACS Daoukro Bangolo Bouaflé 7°N 7°N Daloa YAMOUSSOUKRO Marahoue last four years as measured by Doing Duekoue o Abengourou b GHANA o YAMOUSSOUKRO Dimbokro L Sinfra Guiglo Bongouanou Indenie- Toulepleu Toumodi N'Zi Djuablin Business, Global Competitiveness, Oumé Cavally Issia Belier To Gôh CÔTE D'IVOIRE Monrovia -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Planning Cities

Report No: AUS10013 Public Disclosure Authorized Republic of Côte d'Ivoire Côte d'Ivoire Urbanization Review June 12, 2015 Public Disclosure Authorized . GSURR AFRICA Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized i Standard Disclaimer: This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

Meeting Targets and Maintaining Epidemic Control (Epic) Project

Meeting Targets and Maintaining Epidemic Control (EpiC) Project Cooperative Agreement No. 7200AA19CA00002 CÔTE D’IVOIRE QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT JULY 1 TO SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 SUBMITTED BY FHI 360: OCTOBER 30, 2020 EpiC Côte d’Ivoire Quarterly Progress Report July 1 to September 30, 2020 A. SUMMARY OF KEY RESULTS This report covers activities and performance of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)-funded Meeting Targets and Maintaining Epidemic Control (EpiC) project in Côte d'Ivoire (EpiC CI) for quarter four (Q4) of FY20. The EpiC CI project is being implemented in eight health regions composed of 20 sites, each representing a health district or a commune. In Q4, the project continued to support local implementing partners in providing HIV prevention interventions to key populations (KP) and their sexual partners, as well as care and support to people living with HIV (PLHIV). HIV case finding, linkage to ART, and support for ART retention remained a priority of the project team despite the context of COVID-19. To ensure annual targets were met, the project team provided both virtual and physical technical suppors to implement index testing, and standard outreach activities at targeted hot spots in compliance with the PEPFAR COVID-19 guidelines. In Q3, the project had achieved over 70% of its contractual targets for all indicators except for index testing. To catch-up and meet the minimum requirements for index testing, the project conducted a refresher training for outreach workers who are authorized to perform HIV testing in the community. After the training, index testing implementation was accelerated to boost case identification and meet the annual HTS_TST_POS targets. -

Côte D'ivoire (SHARM- CI): “HIV and Associated Risk Factors Among MSM in Abidjan, Côte D’Ivoire” (FHI 360 Report, January 22, 2013)

FY 2015 Cote d’Ivoire Country Operational Plan (COP) The following elements included in this document, in addition to “Budget and Target Reports” posted separately on www.PEPFAR.gov, reflect the approved FY 2015 COP for Cote d’Ivoire. 1) FY 2015 COP Strategic Development Summary (SDS) narrative communicates the epidemiologic and country/regional context; methods used for programmatic design; findings of integrated data analysis; and strategic direction for the investments and programs. Note that PEPFAR summary targets discussed within the SDS were accurate as of COP approval and may have been adjusted as site- specific targets were finalized. See the “COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit” sheets that follow for final approved targets. 2) COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit includes approved COP 15 targets (targets to be achieved by September 30, 2016). As noted, these may differ from targets embedded within the SDS narrative document and reflect final approved targets. 3) Sustainability Index and Dashboard Approved FY 2015 COP budgets by mechanism and program area, and summary targets are posted as a separate document on www.PEPFAR.gov in the “FY 2015 Country Operational Plan Budget and Target Report.” Côte d’Ivoire Country Operational Plan 2015 Strategic Direction Summary Revised September 17, 2015 Table of Contents Goal Statement ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context............................................................................................4