Phd PROGRAM ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY AND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Association of Pride Organizers 2018 Annual Report 2012 Annual Report

International Association of Pride Organizers 2018 Annual Report 2012 Annual Report InterPride Inc. – International Association of Pride Organizers Founded in 1982, InterPride is the world’s largest organization for organizers of Pride events. InterPride is incorporated in the State of Texas in the USA and is a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization under US law. It is funded by membership dues, sponsorship, merchandise sales and donations from individuals and organizations. OUR VISION A world where there is full cultural, social and legal equality for all. OUR MISSION Empowering Pride Organizations Worldwide. OUR WORK We promote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride on an international level, to increase networking and communication among Pride Organizations and to encourage diverse communities to hold and attend Pride events and to act as a source of education. InterPride accomplishes it mission with Regional Conferences and an Annual General Meeting and World Conference. At the annual conference, InterPride members network and collaborate on an international scale and take care of the business of the organization. InterPride is a voice for the LGBTQ+ community around the world. We stand up for inequality and fight injustice everywhere. Our members share the latest news about their region with us, so we are able to react internationally and make a difference. Regional Director reports contained within this Annual Report are the words, personal accounts and opinions of the authors involved and do not necessarily reflect the views of InterPride as an organization. InterPride accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of material contained within. InterPride may be contacted via [email protected] or our website: Front cover picture was taken at the first Pride in Barbados. -

Annual Report 2014

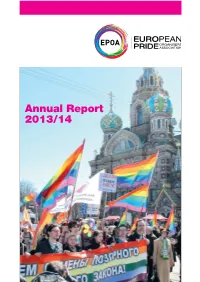

Annual Report 2013/14 EPOA · ANNUAL REPORT 2013/14 Welcome to EPOA! EPOA, the European Pride Organisers Association, had a difficult working year. It is not a secret that maintaining a cross-border non-profit organisation with limited financial means is a daunting task. Add to the mix some new faces and new ideas and fireworks are guaranteed. Unfortunately some of the board members have left us half way through the working year for all sorts of different reasons. But looking back at some of the challenges we came across, it has to be said that the board and its vision has come out even stronger. So with the remaining board members we obviously ensured the proper functioning of the organisation but foremost lined ourselves up towards a better organisa- tion for the future. EPOA, through its members, has an enormous potential for A lot of preparatory work was done towards improving EPOA the future, a reason why we are really actively looking to grow as a whole: search for new members, defining internal proce- this organisation. We are the voice of many LGBTIQ lobby dures, focus on our members’ needs and moving our Euro- groups and that voice should be heard! EuroPride is also a Pride event and its brand to the next level. powerful tool in order towards that same goal. But by bring- ing more members to the table, we will also be able to gener- Talking about EuroPride; we were thrilled with the fantastic ate more energy, more ideas, more support and why not an event our member Oslo Pride put on this year. -

Dossier De Presse 2020 Des Destinations

DOSSIER DE PRESSE 2020 DES DESTINATIONS Présidence OFFICE DU TOURISME DE PORTUGAL; 3, rue de Noisiel;75016 PARIS;Tél. +33 1 56 88 30 84 [email protected]; www.adonet-france.fr Abu Dhabi Quels sont les événements phares de votre pays en 2020 ? 1) Expo 2020 L’exposition universelle aura lieu cette année aux Emirat arabes unis, à Dubaï. Le site se trouvera à peu près à mi-chemin entre Dubai et Abu Dhabi et permettra donc de visiter et de loger dans l’un ou l’autre des deux émirats. Le thème de cette édition sera « Sustainability and Mobility » 2) Ouverture de la Mangrove Walk en janvier Nouveau projet écotouristique de préservation et de valorisation de la mangrove autour d’Abu Dhabi. Une promenade sur pilotis ouvrira à travers la mangrove pour découvrir cet écosystème unique de manière respectueuse pour l’environnement. De nombreuses activités d’éducation pour le grand public et notamment les familles entoureront cette ouverture. 3) Ultra Abu Dhabi et Abu Dhabi Music Week Première édition de ce nouveau rendez-vous musical. Ultra Abu Dhabi sera le premier festival de musique électronique à se tenir au Moyen-Orient. Les EAU feront ainsi partie des 20 pays à travers le monde à accueillir cet événement multi-localisé. Quelles sont les nouveautés concernant l'offre de votre destination ? 1) Fouquet’s at Louvre Abu Dhabi Le Fouquet’s Abu Dhabi ouvrira au sein du Louvre Abu Dhabi en 2020 avec une carte imaginée par le Chef trois étoiles Michelin Pierre Gagnaire. 2) Yas Bay Ce nouveau quartier de Yas Island ouvrira courant 2020 et comportera un nouveau front de mer aménagé, 3 hôtels, de nombreux nouveaux restaurants et boutiques, ainsi qu’une nouvelle salle de concert pouvant accueillir en 5000 et 18 000 personnes. -

A Project of the Human Rights Committee of Interpride Un Proyecto Del Comité De Derechos Humanos De Interpride 2016 | 2017

International Association of Pride Organizers A Project of the Human Rights Committee of InterPride Un proyecto del Comité de Derechos Humanos de InterPride 2016 | 2017 InterPride member | miembro 2016 | 2017 PrideRadar InterPride Inc. – International Association of InterPride Inc., Asociación Internacional de Organizadores Pride Organizers de Eventos del Orgullo Lésbico, Gay, Bisexual, Transgénero Founded in 1982, InterPride is the world’s largest organization for orga- e Intersexual – en inglés International Association of nizers of Pride events. InterPride is incorporated in the State of Texas in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Pride the USA and is a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization under US law. It is Organizers. funded by membership dues, sponsorship, merchandise sales and do- nations from individuals and organizations. Fundada en 1982, InterPride es la asociación de organizadores de even- tos (marchas, protestas y celebraciones) del orgullo LGBTI —conocidos Our Vision también como prides—, más grande del mundo. InterPride esta esta- A world where there is full cultural, social and legal equality for all. blecida en el estado de Texas Estados Unidos bajo el apartado 501(c)(3) como una organización exenta de impuestos de acuerdo a las leyes Our Mission fiscales estadounidenses. InterPride esta financiada por las cuotas de Empowering Pride Organizations Worldwide sus miembros, patrocinios, la venta de artículos, y de donaciones de individuos y organizaciones. We promote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride on an inter- national level and encourages diverse communities to hold and attend Nuestra misión Pride Events. InterPride increases networking, communication and edu- La misión de InterPride es promover el movimiento del orgullo LGBTI a cation among Pride Organizations and collaborates with other LGBTI escala internacional y alentar a que se mantengan vigentes y que se and Human Rights organizations. -

3° Seminario Della Telefonia Sociale

C.I.G. Centro di Iniziativa Gay Arcigay Milano ONLUS VERBALE della CONSULTA del 7 Luglio 2017 Il giorno 7 del mese di Luglio dell’anno 2017 alle ore 21.30 presso la sede sociale in Milano, via Bezzecca n. 3, si è riunita la Consulta del C.I.G. Centro di Iniziativa Gay, Arcigay Milano ONLUS, per deliberare sul seguente ordine del giorno: 1. Corso di Formazione 2. Costituzione Gruppo Intersessualità 3. Sostegno Illecite Visioni 2017 4. Premio Testi Teatrali 5. Nuova Sede 6. Punto situazione Milano Pride 7. Varie ed eventuali Constatata la presenza del numero legale, si dichiara aperta la seduta. Viene eletto Presidente della Seduta Pellegatta Fabio e Segretario Verbalizzante Salinari Alessio. Il Presidente della seduta accerta la presenza dei seguenti componenti della Consulta e Invitati Permanenti: Pellegatta Fabio (Presidente) Baldanza Fabio (Vicepresidente) Salinari Alessio (delegato) Fabio Galantucci (delegato) Muzzetta Roberto (delegato) Raffa Aurelio (Delegato) Lopriore Simone (Sezione accoglienza) Angelo Palmeri (Sez. Scuola) Deserti Diego (Sez Salute) Assente/i giustificato/i: Sezione Cultura, Pigino Walter (Tesoriere), Garbardella Laura (delegato), Massacci Alessandra (sezione biblioteca), Davide Veronese (sez. Telefono amico). Raffa Aurelio rassegna le sue dimissione dalla consulta del CIG per motivi personali Il Presidente della Seduta illustra il primo punto all’ordine del giorno: Corso di Formazione Il gruppo accoglienza in collaborazione con il gruppo scuola del CIG Arcigay presentano una proposta di progetto di corso di formazione per nuovi volontari per l’anno 2017/2018 finalizzato allo svolgimento di un servizio volontario all’interno dei gruppi/sezioni dell’associazione. La data di inizio corso sarà il 5 Ottobre 2017 presso la casa dei diritti di Milano. -

Se Vuoi Abbattere Il Capitalismo E Il Suo Governo Diretto Dal Nuovo

Settimanale Fondato il 15 dicembre 1969 Nuova serie - Anno XL - N. 27 - 7 luglio 2016 Risultato del Referendum LA GRAN BRETAGNA ESCE DALLA UE. SI’ 51,9% NO 48,1%. DURISSIMO COLPO A ALTA FINANZA, BANCHE E CITY Cameron si è dimesso. I governanti europei prendono misure per evitare il tracollo della Unione e la fuga dei popoli da essa. Per Renzi l’Europa Se vuoi abbattere il capitalismo imperialista è “la nostra casa che va ristrutturata” e il suo governo diretto dal nuovo INDIRE IL REFERENDUM ANCHE IN ITALIA PAG. 2 Mussolini Renzi PRENDENDO A PRETESTO LA DEMOCRATICITÀ E LA TRASparENZA oselitismo 2016 La Camera approva una Campagna di pr legge che impone la concezione borghese del partito, istituzionalizza i partiti e ficca il naso dello Se vuoi Stato al loro interno I PARTITI DEVONO RIMANERE conquistare ASSOCIAZIONI NON RICONOSCIUTE PAGG. 4-5 il socialismo e il potere politico Con la “Costituente comunista” a Bologna NASCE UN da parte del proletariato NUOVO PCI REVISIONISTA “Si ispira ai valori della Costituzione e si richiama al miglior patrimonio politico ed ideologico dell’esperienza storica del PCI, da Gramsci a Berlinguer, e in particolar modo al pensiero gramsciano e togliattiano” EntraPRENDI CONTATTO CON ILnel PMLI! CHE I SINCERI COMUNISTI VALUTINO ATTENTAMENTE LA NUOVA-VECCHIA PARTITO MARXISTA-LENINISTA ITALIANO Sede centrale: Via Antonio del Pollaiolo, 172a - 50142 FIRENZE PROPOSTA REVISIONISTA in proprio stampato Tel. e fax 055.5123164 e-mail: [email protected] www.pmli.it PAG. 7 A Modena, Napoli e Fucecchio BANCHINI E VOLANTINAGGI DEL PMLI PER IL NO ALLA CONTRORIFORMA PIDUISTA E FASCISTA DEL SENATO PAG. -

International Association of Pride Organizers

International Association of Pride Organizers 2016 Annual Report 2012 Annual Report InterPride Inc. – International Association of Pride Organizers Founded in 1982, InterPride is the world’s largest organization for organizers of Pride events. InterPride is incorporated in the State of Texas in the USA and is a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization under US law. It is funded by membership dues, sponsorship, merchandise sales and donations from individuals and organizations. OUR VISION A world where there is full cultural, social and legal equality for all. OUR MISSION Empowering Pride Organizations Worldwide. OUR WORK We promote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride on an international level, to increase networking and communication among Pride Organizations and to encourage diverse communities to hold and attend Pride events and to act as a source of education. InterPride accomplishes it mission with Regional Conferences and an Annual General Meeting and World Conference. At the annual conference, InterPride members network and collaborate on an international scale and take care of the business of the organization. InterPride is a voice for the LGBTI community around the world. We stand up for inequality and fight injustice everywhere. Our member organizations share the latest news so that can react internationally and make a difference. Regional Director reports contained within this Annual Report are the words, personal accounts and opinions of the authors involved and do not necessarily reflect the views of InterPride as an organization. InterPride accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of material contained within. InterPride may be contacted via email [email protected] or via our website. -

RASSEGNA STAMPA Giugno 2020 INDICE

RASSEGNA STAMPA giugno 2020 INDICE SG COMPANY 20/06/2020 QN - Il Giorno - Nazionale 9 Lo iodio essenziale per stare bene 12/06/2020 DailyMedia 10 Daikin sceglie ancora SG Company per presentare il nuovo Mini VRV 5 09/06/2020 DailyNet 11 Obecity goes digital: nasce Obecity Digital Village 08/06/2020 DailyMedia 12 Obecity goes digital: nasce Obecity Digital Village con Wired e LifeGate partner 04/06/2020 Forbes Italia 14 Il signore degli eventi 12/06/2020 DailyNet 16 Daikin sceglie di affidarsi ancora una volta a SG Company 08/06/2020 Pubblicom Now 17 SG Company presenta il nuovo "Obecity Digital Village" 12/06/2020 Pubblicom Now 18 Daikin Italy sceglie SG Company per presentare il climatizzatore Mini VRV 5 SG COMPANY WEB 29/06/2020 FTA Online 09:06 20 SG Company: finanza, controllo, amministrazione, risorse umane e IT le deleghe al neoconsigliere Merone 26/06/2020 Public Now 21 SG Company S.p.A. ? Consiglio di Amministrazione per il conferimento di deleghe e cooptazione di nuovo consigliere 26/06/2020 Trend Online.com 07:55 22 Ftse Mib: Fca, Cattolica Assicurazioni e Mediaset sotto la lente 22/06/2020 finanza.lastampa.it 08:15 23 Appuntamenti e scadenze: settimana del 22 giugno 2020 22/06/2020 tgcom.it 05:03 25 Winetelling protagonisti della Rainbow Edition per la Milano Pride Week dal 19 al 28 giugno 19/06/2020 finanza.tgcom24.mediaset.it 28 COMMENTO AIM: indice positivo, in luce Sebino 17/06/2020 artumagazine.it 09:00 29 Milano Wine Week versione rainbow per discutere di diversità e inclusione 12/06/2020 brand-news.it 11:57 30 Daikin sceglie ancora SG Company per il lancio più importante del 2020 12/06/2020 brand-news.it 09:48 31 Daikin sceglie ancora SG Company per il lancio più importante del 2020 11/06/2020 AdvExpress.it 15:39 32 Daikin sceglie SG Company per presentare il nuovo climatizzatore Mini VRV 5 10/06/2020 24oreNews.it 34 MILANO. -

2014 Annual Report 2012 Annual Report

International Association of Pride Organizers 2014 Annual Report 2012 Annual Report InterPride Inc. – International Association of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Pride Organizers Founded in 1982, InterPride is the world’s largest organization for organizers of Pride events. InterPride is incorporated in the State of Texas in the USA and is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization under US law. It is funded by membership dues, sponsorship, merchandise sales and donations from individuals and organizations. VISION InterPride’s vision is a world where there is full cultural, social and legal equality for all. MISSION InterPride’s mission is to increase the capacity of our network of LGBTI Pride organi- zations around the world to raise awareness of cultural and social inequality, and to effect positive change through education, collaboration, advocacy and outreach. InterPride exists:To promote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride on an international level, to increase networking and communication among Pride Organi- zations and to encourage diverse communities to hold and attend Pride events and to act as a source of education. InterPride accomplishes it mission with Regional Conferences and an Annual World Conference (AWC). At the annual conference, InterPride members network and col- laborate on an international scale and take care of the business of the organization. InterPride is a voice for the LGBTI community around the world. We stand up for in- equality and fight injustice everywhere. Our member organizations share the latest news so that can react internationally and make a difference. Regional Director reports contained within this Annual Report are the words, personal accounts and opinions of the authors involved and do not necessarily reflect the views of InterPride as an organization. -

GLAS-Activity-Report-2019-English

GLAS Foundation’s Annual Report 2 glasfoundation.bg GLAS would like to thank the local LGBTI community for standing up for their rights and friends. We would also like to thank all the international and local partnering organizations, companies, authorities, medias, allies, activists and volunteers who contributed with their time and energy in 2019. The fight is not possible without you! GLAS’s annual report was coordinated and edited by Simeon Vasilev and Hristo Serafimov. The report covers activities between 1st January and 31st December 2019. 26 Table of Contents GLAS with international recognition on the Global Innovative Advocacy Summit Ruth Koleva’s video “Candy Coated”, (p. 2) created in partnership with GLAS (p. 15) 12th edition of Sofia Pride (p. 3) Community clubs for literature, cinema and board games Sofia Pride Arts — Sofia Pride’s (p. 16) culture program (p. 4) GLAS with a special program at Sofia Film Fest and the screenings of “Coming Out” in The “100% Different —#StopHate” campaign Plovdiv and Kardzhali (p. 5) (p. 17) The #Balkan Pride exhibition Screening of “House of Boys” and discussion with (p. 6) the director Jean-Claude Schilm (p. 18) The Homosoc exhibition (p. 7) GLAS Foundation’s participation in Sofia Game Night The national representative survey on (p. 19) the levels of homophobia (p. 8) Rainbow Hub (p. 20) The Pan-European survey on sexual health GLAS’ balls (p. 9) (p. 21) The platform “Work It OUT” with New partnerships recognition from Reward Getaway, (p. 22) the WIO club and our participation in “Diversity Pays Off” GLAS in the media (p. -

28 Singer Tom 4 Nationwide Pride 34 Jennifer Morales' Debut 40

28 Singer Tom Goss, a native of Kenosha, loves coming home to visit. This year’s 40 Madison’s FIVE nightclub is visit includes a saved by donations from patrons & 4 Nationwide Pride headlining fans all over the country who didn’t WiG gives you the skinny on performance at 34 Jennifer Morales’ debut want to lose another iconic gay club Pride festivities around the PrideFest Mil- novel Meet Me Halfway has nation and the world. that has been a home away from waukee. Milwaukee written all over it. home to so many over the years. Pride 2 WISCONSINGAZETTE.COM | June 4, 2015 WISCONSINGAZETTE.COM | June 4, 2015 Pride 3 Pride 4 WISCONSINGAZETTE.COM | June 4, 2015 LGBT communities celebrate Pride nationwide Compiled By Lisa Neff Pride is celebrated in thousands of JUNE Staff writer cities around the world, from Adelaide, =Through June 7: Buffalo Pride Fest, Buf- When he was a kid, Philippe Rodriguez Australia, to Zurich, Switzerland. falo, New York; Pride Texas, El Paso; Gay knew the first sun–kissed days of June LGBT communities in hundreds of U.S. Days, Orlando, Florida; Capital Pride, meant school vacation was just ahead. cities observe Pride, from Albuquerque, Washington, D.C. But since he came out four years ago, New Mexico, to Salisbury, North Carolina. sun and June mean Pride for Rodriguez, “Our parade is one of the largest in all of = June 4: Utah Pride, Salt Lake City who is looking forward to three days of New Mexico,” proud Pride celebrant Sandi = June 5–7: Kansas Diversity, Kansas City, PHOTO: COURTESY entertainment and education, community Gray said of the Albuquerque festivities Kansas; PrideFest Milwaukee (parade Performers on the Pride circuit in 2015 and culture at PrideFest, which takes place that take place on June 13. -

Avvocatura Per I Diritti Lgbti - Rete Lenford

CURRICULUM VITAE DELL’ASSOCIAZIONE AVVOCATURA PER I DIRITTI LGBTI - RETE LENFORD DATI GENERALI Denominazione Avvocatura per i diritti LGBTI APS Sede Via Sant’Alessandro 14 – 24122 Bergamo Telefono e fax +39 035 0034659 Email [email protected] Data e luogo di 6 dicembre 2007, Firenze costituzione Presidente Avv.ta Miryam Camilleri Telefono +39 333 6630586 Email [email protected] Codice fiscale e 06006020488 partita IVA EU-VAT 06006020488 Web www.retelenford.it fb: @Avvocatura per i Diritti LGBTI – Rete Lenford ig: @retelenford tw: @ReteLenford Iscrizione a registri e Membro della Fundamental Rights Platform (FRP) presso la associazioni Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) dell’Unione Europea dal 2009. Membro di ILGA Europe – the European Region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) Iscritta al numero 1130 del “Registro delle associazioni e degli enti che svolgono attività nel campo della lotta alle discriminazioni”, di cui all’articolo 6 del decreto legislativo 9 luglio 2003, n. 215, tenuto dall’Ufficio nazionale antidiscriminazioni razziali, presso il Dipartimento per le pari opportunità della Presidenza del Consiglio dei ministri. Iscritta al n. 116 della sez. F) Promozione Sociale del Registro provinciale di Bergamo delle Associazioni senza scopo di lucro, ai sensi della legge n. 383 del 2000 e della legge regionale lombarda n. 1 del 2008. Membro della “Consulta Permanente per il contrasto ai crimini d’odio e ai discorsi d’odio” istituita con D.M.14/12/2017 dal Ministro della Giustizia. Riconoscimenti 2011 - Conferimento di una targa di rappresentanza del istituzionali Presidente della Repubblica al Convegno internazionale “La protezione internazionale per orientamento sessuale e identità di genere”, Palermo, Villa Zito, 25-26 novembre 2014 – Conferimento della Civica Benemerenza da parte del Comune di Bergamo.