Hugo Pratt's and Milo Manara's Indian Summer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science Fiction in Argentina: Technologies of the Text in A

Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Revised Pages DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS, an imprint of the University of Michigan Press, is dedicated to publishing work in new media studies and the emerging field of digital humanities. Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Technologies of the Text in a Material Multiverse Joanna Page University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2016 by Joanna Page Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial- No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Page, Joanna, 1974– author. Title: Science fiction in Argentina : technologies of the text in a material multiverse / Joanna Page. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015044531| ISBN 9780472073108 (hardback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472053100 (paperback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472121878 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Science fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | Literature and technology— Argentina. | Fantasy fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Science Fiction & Fantasy. | LITERARY CRITICISM / Caribbean & Latin American. Classification: LCC PQ7707.S34 P34 2016 | DDC 860.9/35882— dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015044531 http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/dcbooks.13607062.0001.001 Revised Pages To my brother, who came into this world to disrupt my neat ordering of it, a talent I now admire. -

“War of the Worlds Special!” Summer 2011

“WAR OF THE WORLDS SPECIAL!” SUMMER 2011 ® WPS36587 WORLD'S FOREMOST ADULT ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE RETAILER: DISPLAY UNTIL JULY 25, 2011 SUMMER 2011 $6.95 HM0811_C001.indd 1 5/3/11 2:38 PM www.wotw-goliath.com © 2011 Tripod Entertainment Sdn Bhd. All rights reserved. HM0811_C004_WotW.indd 4 4/29/11 11:04 AM 08/11 HM0811_C002-P001_Zenescope-Ad.indd 3 4/29/11 10:56 AM war of the worlds special summER 2011 VOlumE 35 • nO. 5 COVER BY studiO ClimB 5 Gallery on War of the Worlds 9 st. PEtERsBuRg stORY: JOE PEaRsOn, sCRiPt: daVid aBRamOWitz & gaVin YaP, lEttERing: REmY "Eisu" mOkhtaR, aRt: PuPPEtEER lEE 25 lEgaCY WRitER: Chi-REn ChOOng, aRt: WankOk lEOng 59 diVinE Wind aRt BY kROmOsOmlaB, COlOR BY maYalOCa, WRittEn BY lEOn tan 73 thE Oath WRitER: JOE PEaRsOn, aRtist: Oh Wang Jing, lEttERER: ChEng ChEE siOng, COlORist: POPia 100 thE PatiEnt WRitER: gaVin YaP, aRt: REmY "Eisu" mOkhtaR, COlORs: ammaR "gECkO" Jamal 113 thE CaPtain sCRiPt: na'a muRad & gaVin YaP, aRt: slaium 9. st. PEtERsBuRg publisher & editor-in-chief warehouse manager kEVin Eastman JOhn maRtin vice president/executive director web development hOWaRd JuROFskY Right anglE, inC. managing editor translators dEBRa YanOVER miguEl guERRa, designers miChaEl giORdani, andRiJ BORYs assOCiatEs & JaCinthE lEClERC customer service manager website FiOna RussEll WWW.hEaVYmEtal.COm 413-527-7481 advertising assistant to the publisher hEaVY mEtal PamEla aRVanEtEs (516) 594-2130 Heavy Metal is published nine times per year by Metal Mammoth, Inc. Retailer Display Allowances: A retailer display allowance is authorized to all retailers with an existing Heavy Metal Authorization agreement. -

A Paródia Do Drama Shakespeariano Como Evolução Das Histórias Em Quadrinhos

LEONARDO VINICIUS MACEDO PEREIRA AI DE TI, YORICK BROWN: A PARÓDIA DO DRAMA SHAKESPEARIANO COMO EVOLUÇÃO DAS HISTÓRIAS EM QUADRINHOS Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, para obtenção do título de Magister Scientiae. VIÇOSA MINAS GERAIS – BRASIL 2015 Ficha catalográfica preparada pela Biblioteca Central da Universidade Federal de Viçosa - Câmpus Viçosa T Pereira, Leonardo Vinícius Macedo, 1981- P434a Ai de ti, Yorick Brown : a paródia do drama shakespeariano 2015 como evolução das histórias em quadrinhos / Leonardo Vinícius Macedo Pereira. – Viçosa, MG, 2015. viii, 124f. : il. (algumas color.) ; 29 cm. Inclui anexos. Orientador: Sirlei Santos Dudalski. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Referências bibliográficas: f.105-115. 1. Literatura comparada. 2. Literatura - Adaptação. 3. Histórias em quadrinhos. 4. Paródia. 5. Shakespeare, William,1564-1616 . I. Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Departamento de Letras. Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras. II. Título. CDD 22. ed. 809 LEONARDO VINICIUS MACEDO PEREIRA AI DE TI, YORICK BROWN: A PARÓDIA DO DRAMA SHAKESPEARIANO COMO EVOLUÇÃO DAS HISTÓRIAS EM QUADRINHOS Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, para obtenção do título de Magister Scientiae. APROVADA: 13 de março de 2015. __________________________ __________________________ Fulvio Torres Flores Nilson Adauto Guimarães da Silva ____________________________ -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

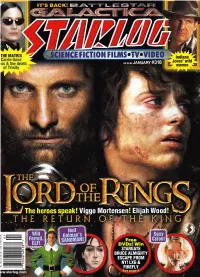

Starlog Magazine

THE MATRIX SCIENCE FICTION FILMS*TV*VIDEO Indiana Carrie-Anne 4 Jones' wild iss & the death JANUARY #318 r women * of Trinity Exploit terrain to gain tactical advantages. 'Welcome to Middle-earth* The journey begins this fall. OFFICIAL GAME BASED OS ''HE I.l'l't'.RAKY WORKS Of J.R.R. 'I'OI.KIKN www.lordoftherings.com * f> Sunita ft* NUMBER 318 • JANUARY 2004 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE ^^^^ INSIDEiRicinE THISti 111* ISSUEicri ir 23 NEIL CAIMAN'S DREAMS The fantasist weaves new tales of endless nights 28 RICHARD DONNER SPEAKS i v iu tuuay jfck--- 32 FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY Creator is \ 1 *-^J^ Joss Whedon glad to see his saga out on DVD 36 INDY'S WOMEN L/UUUy ICLdll IMC dLLIUII 40 GALACTICA 2.0 Ron Moore defends his plans for the brand-new Battlestar 46 THE WARRIOR KING Heroic Viggo Mortensen fights to save Middle-Earth 50 FRODO LIVES Atop Mount Doom, Elijah Wood faces a final test 54 OF GOOD FELLOWSHIP Merry turns grim as Dominic Monaghan joins the Riders 58 THAT SEXY CYLON! Tricia Heifer is the model of mocmodern mini-series menace 62 LANDniun OFAC THETUE BEARDEAD Disney's new animated film is a Native-American fantasy 66 BEING & ELFISHNESS Launch into space As a young man, Will Ferrell warfare with the was raised by Elves—no, SCI Fl Channel's new really Battlestar Galactica (see page 40 & 58). 71 KEYMAKER UNLOCKED! Does Randall Duk Kim hold the key to the Matrix mysteries? 74 78 PAINTING CYBERWORLDS Production designer Paterson STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., Owen 475 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

Mason 2015 02Thesis.Pdf (1.969Mb)

‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Author Mason, Paul James Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3741 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367413 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Paul James Mason s2585694 Bachelor of Arts/Fine Art Major Bachelor of Animation with First Class Honours Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Group Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts (DVA) June 2014 Abstract: What methods do writers and illustrators use to visually approach the comic book page in an American Superhero form that can be adapted to create a professional and engaging Australian hero comic? The purpose of this research is to adapt the approaches used by prominent and influential writers and artists in the American superhero/action comic-book field to create an engaging Australian hero comic book. Further, the aim of this thesis is to bridge the gap between the lack of academic writing on the professional practice of the Australian comic industry. In order to achieve this, I explored and learned the methods these prominent and professional US writers and artists use. Compared to the American industry, the creating of comic books in Australia has rarely been documented, particularly in a formal capacity or from a contemporary perspective. The process I used was to navigate through the research and studio practice from the perspective of a solo artist with an interest to learn, and to develop into an artist with a firmer understanding of not only the medium being engaged, but the context in which the medium is being created. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Graphic Narrative: Comics in Contemporary Art

An Elective Course for Undergraduate and Graduate Students of any discipline and for English Language Students GRAPHIC NARRATIVE IN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE & ART: EVOLUTION OF COMIC BOOK TO GRAPHIC NOVEL Basic Requirements: Appropriate language skills required by the University. This course should be of interest to anyone concerned with verbal & visual communications, popular forms, mass culture, history and its representation, colonialism, politics, journalism, writing, philosophy, religion, mythology, mysticism, metaphysics, cultural exchanges, aesthetics, post-modernism, theatre, film, comic art, collections, popular art & culture, literature, fine arts, etc. This course may have a specific appeal to fans and/or to those who are curious about this vastly influential, widely popular, most complex and thought-provoking work of contemporary literature and art form, the ‘Comics’; however it does not presume a prior familiarity with graphic novels and/or comics, just an overall enthusiasm to learn new things from a new angle and an open mind. Prerequisites: FA489: ‘By consent’ selection of students. FA490: Upon successful completion of FA489. Co-requisites: FA489: Freshmen who graduated from a high school with an English curriculum or passed BU proficiency test with an A; & sophomore, junior, senior students. FA490: Successful completion of FA 489. No requisites: FA 49I, FA49J, FA49V. Recommended Preparation: Reading all of the required readings and as many from the suggested reading list. Idea Description: Is ‘comics’ a form of both literature and art? Certainly the answer is “yes” but there are many people who reject the idea, yet many other people call those people old-school intellectuals. However, in recent years, many scholars, critics and faculty alike have accepted ‘comics’, often dubbed by many publishers as ‘graphic novel’, as a respected form of both literature and art. -

The Rip Off Press Mail Order Catalog

Spread some cheer this year, with comix from The Rip Off Press Mail Order Catalog No-Pictures Edition Stuff for sale December 2012 THE NO PICTURES VERSION OF THE RIP OFF PRESS MAIL ORDER CATALOG Need to see pictures of the items we sell? Visit our website! If you don't own a com- WHAT TO DO IN CASE OF ORDER PROBLEMS puter, go to your public library and somebody will be happy to help you log on: www. If there is any problem with your order, probably the quickest and most effective way to ripoffpress.com. After our previous website’s hosting company vanished without a trace deal with it is to send us an e-mail. That way you can get through to us at your conve- in August of 2012, we have not yet gotten online ordering enabled. But you can get a nience, and we will see your message within a few hours at a time when we have access better idea of what you want, then place a mail order from this product listing or from to all of our records. Our e-mail address is [email protected]. If you’re not yet the Adobe PDF format order form available as a download on our home page. one of the millions of people with access to e-mail, you can call us by phone. Please call 530 885-8183. If we’re not there to answer your call you can usually leave a message PLACING YOUR ORDER on our answering machine. You may also notify us of order problems by letter (P.O. -

Downloadable in Late October and in Your Mailbox in Early to Mid-November

Featured New Items FANTASTIC PAINTINGS OF FRAZETTA On our Cover Highly Recommended. By David Spurlock. Afterword by Frank Frazetta Jr. THE BIG TEASE J. David Spurlock started crafting this A Naughty and Nice Collection book by reviving the original million-selling Highly Recommend- 1970s mass market art book, Fantastic Art ed. By Bruce Timm. of Frank Frazetta. Then he expanded and Bruce Timm has revised it to include twice as many images been creating elegant and presents them at a much larger cof- drawings of women fee-table book size of 10.5 x 14.5 inches! for over 30 years, and The collection is brimming with both classic nearly all of these and previously unpublished works of the charming nudes were subjects Frazetta is best remembered for, drawn purely for fun including barbarians, beasts, and buxom after-hours. This beauties. Vanguard, 2020. book collects all three FANPFH. HC, 10x15, 112pg, PC $39.95 Teaser collections from FANTASTIC PAINTINGS OF 2011 to 2013, long sold FRAZETTA Deluxe out. Plus Surrender, Signed by Spurlock and Frank Frazetta, My Sweet from 2015. Jr. 16 bonus pages, variant illustrated In addition, Timm has created new material espe- slipcase. Highly Recommended. cially for this collection and delved into his personal Vanguard, 2020. archives to share pieces not shown before, culmi- FANPFD. HC, 10x15, 128pg, PC $69.95 nating in more than 75 additional pages of material. Abundant nudity. Oversized. Flesk, 2020. Due Oct. SENSUOUS FRAZETTA Deluxe: Mature Readers. 16 Bonus Pages, Variant Cover. BIGT. SC, 9x12, 208pg, PC $39.95 Mature Readers. SENFD. $69.95 Cover Image courtesy of Bruce Timm and Flesk TELLING STORIES The Comic Art of Publications. -

Here Is SHAM04

Featured New Items On our Cover MIRAGE ART QUEST OF ALEX NINO Vol 2 Signed Signed, numbered & limited, 500! Our Highest Recommendation. A fabu- lous new oversized artbook, mostly in full color, with 5 gatefolds of new artwork. Much never seen before art work in a wide variety of SHAME TRILOGY Back in stock. Highly Recommended. By Lovern Kindzierski. styles and media. Contents Art by John Bolton. The purest woman on earth allows herself in this book are Niño’s art- one selfish thought, and conceives the most evil woman the work from the past 20 years, world has ever seen. A classic adult fantasy, with absolutely a companion to his 2008 gorgeous artwork, a rich story, and abundant nudity. Virtue gets volume 1, which is long out the daughter she wished for, Shame, releasing this powerful of print. Amazing fantasy woman to a world ill-prepared for her campaign of evil. Plus the images of other worlds, monsters, nymphs, creatures first 10 pages of the first book in the Tales of Hope trilogy, John and stunning alien landscapes. Alex Niño, 2019. Bolton’s original pencil layouts, an interview with Lovern and MIRAGHS. HC, 10x13, 200pg, PC $150.00 John, and background material. Previously published as three MIRAGE ART QUEST OF ALEX NINO Vol 2 separate graphic novels. Renegade, 2016. Mature Readers. with Drawing SHAMH. HC, 7x11, 224pg, FC $29.99 Signed and Limited to 500, with a 7x10 original pen SHAME Vol 4 Hope & ink drawing, each unique. Our Highest Recommen- A gorgeous, richly drawn modern fairy tale. Highly Recom- Alex Niño, 2019. -

Inglese Facilitato Modifiche.Pdf

Animation (Animation room) “Cells” (short for celluloid) is the name of the transparent sheets used for animation. Before computers, characters were drawn and coloured on these “cells”. After the cells were superimposed against the relevant background and photographed. In 1914, in the U.S. cells made animation industry possible and were first used in the US. Many comic strip characters became cinema stars, like the Peanuts and Lupin III. Other characters developed for movies were then put on paper: Mickey Mouse for instance and Bruno Bozzetto’s Vip, the character created in 1968 for the movie VIP, My Brother Superman. Little Nemo Winsor McCay was one of the first and foremost comic and animation artists. Little Nemo was his best known character. In 1905, Little Nemo first appeared in the New York Herald. Its surprising and extraordinary adventures always ended with him suddenly waking up, revealing it was all but a beautiful dream. In 1911 Winsor McCay made a short animation movie, and drew thousands and thousands of frames, as the live shooting shows. With Nemo, there where Flip Flap the clown Flip, African Little Imp and Pricess Slumberland, as also the City of Dreams. Movies from the 1960s (ramp 1) In the Nineteen- Sixties the world of comics saw the rise of strips for an adult readers and of the monthly “Linus” with Valentina, Barbarella and Dick Tracy. Our journey starts here. Before digital effects you could see the wrinkles on superheroes’ suits, and many of the interpretations were funny and inconsistent with the drawing’s creation. Even great U.S.