In Uence of Socio-Spatial Determinants on Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drivers of Rift Valley Fever Epidemics in Madagascar

Drivers of Rift Valley fever epidemics in Madagascar Renaud Lancelota,b,1, Marina Beral´ b,c,d, Vincent Michel Rakotoharinomee, Soa-Fy Andriamandimbyf, Jean-Michel Heraud´ f, Caroline Costea,b, Andrea Apollonia,b,Cecile´ Squarzoni-Diawg, Stephane´ de La Rocquea,b,h,i, Pierre B. H. Formentyj,Jer´ emy´ Bouyera,b, G. R. William Wintk, and Eric Cardinaleb,c,d aFrench Agricultural Research and International Cooperation Organization for Development (Cirad), Department of Biological Systems (Bios), UMR Animals, Health, Territories, Risks, and Ecosystems (Astre), Campus International de Baillarguet, 34398 Montpellier, France; bFrench National Agricultural Research Center for International Development, Animal Health Department, UMR Astre, Campus International de Baillarguet, 34398 Montpellier, France; cCirad, Bios Department, UMR Astre, 97490 Sainte Clotilde, La Reunion,´ France; dCentre de Recherche et de Veille sur les Maladies Emergentes´ de l’Ocean´ Indien, 97490 Sainte Clotilde, La Reunion,´ France; eMinistere` de l’Agriculture, de l’Elevage et de la Peche,ˆ Direction des Services Vet´ erinaires,´ Ambatofotsikely, BP 530 Antananarivo 101, Madagascar; fUnite´ de Virologie, Institut Pasteur de Madagascar, BP 1274 Antananarivo 101, Madagascar; gAnimal Production and Health Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 00153 Rome, Italy; hWorld Organization for Animal Health, 75017 Paris, France; iInternational Health Regulations Monitoring Procedure and Information Team, Global Capacity and Response Department, World Health Organization (WHO), 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland; jEmerging and Epidemic Zoonotic Diseases, Pandemic and Epidemic Disease Department, WHO, Geneva 27, Switzerland; and kDepartment of Zoology, Environmental Research Group Oxford, Oxford OX1 3PS, United Kingdom Edited by Burton H. Singer, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, and approved December 8, 2016 (received for review May 18, 2016) Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a vector-borne viral disease widespread the slaughtering of viremic animals (11): Blood aerosol produced in Africa. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

Madagascar Country Office Covid-19 Response

COVID-19 Situation Report, Madagascar | July 29th, 2020 Madagascar Country Office Covid-19 response July 29th 2020 Situation in Numbers 10432 cases across 19 regions 93 deaths 101 RECOVERED July 29th 2020 Highlights Funding status th th From May 17 to July 29 2020, the positive COVID-19 cases growth curve fund decupled exponentially from 304 to 10,432 cases with 0.89% of fatality rate received in 19 out of 22 affected regions (all except Androy, Atsimo Atsinanana and $1.19 Melaky). funding gap The epicenter remains the capital Antananarivo with very high community $3.45 transmission. The hospitalization capacity was reached in central hospitals which led to care decentralization for asymptomatic and pauci- symptomatic patients whilst hospitalization is offered in priority for carry forward moderate, severe and critical patients. $2.35 UNICEF supports moderate, severe and critical patients’ care by supplying oxygen (O2) to central hospitals, helping saving lives of most severe patients. Thus far, 240,000 families have received a cash transfer of 100,000 Ariary (26 USD) to meet their basic needs. In collaboration with the Government and through the Cash Working Group, UNICEF coordinates the second wave of emergency social assistance in the most affected urban and peri- urban areas. However, UNICEF’s appeal for emergency social protection support, remains unfunded. Around 300,000 children received self-study booklets while distribution to another 300,000 children is being organized. UNICEF is monitoring the promoted health measures to be put in place prior the tentative examination dates for grade, 7, 3 and Terminal. Funding 600,000 Overview people in most affected cities benefitted from a subsidized access to water, via Avo-Traina programme while more than 20,000 taxi were disinfected and supported with hydroalcoholic gel and masks in Antananarivo. -

AP ART HISTORY--Unit 5 Study Guide (Non Western Art Or Art Beyond the European Tradition) Ms

AP ART HISTORY--Unit 5 Study Guide (Non Western Art or Art Beyond the European Tradition) Ms. Kraft BUDDHISM Important Chronology in the Study of Buddhism Gautama Sakyamuni born ca. 567 BCE Buddhism germinates in the Ganges Valley ca. 487-275 BCE Reign of King Ashoka ca. 272-232 BCE First Indian Buddha image ca. 1-200 CE First known Chinese Buddha sculpture 338 CE First known So. China Buddha image 437 CE The Four Noble Truthsi 1. Life means suffering. Life is full of suffering, full of sickness and unhappiness. Although there are passing pleasures, they vanish in time. 2. The origin of suffering is attachment. People suffer for one simple reason: they desire things. It is greed and self-centeredness that bring about suffering. Desire is never satisfied. 3. The cessation of suffering is attainable. It is possible to end suffering if one is aware of his or her own desires and puts and end to them. This awareness will open the door to lasting peace. 4. The path to the cessation of suffering. By changing one’s thinking and behavior, a new awakening can be reached by following the Eightfold Path. Holy Eightfold Pathii The principles are • Right Understanding • Right Intention • Right Speech • Right Action • Right Livelihood • Right Effort • Right Awareness • Right Concentration Following the Eightfold Path will lead to Nirvana or salvation from the cycle of rebirth. Iconography of the Buddhaiii The image of the Buddha is distinguished in various different ways. The Buddha is usually shown in a stylized pose or asana. Also important are the 32 lakshanas or special bodily features or birthmarks. -

Fill the Nutrient Gap Madagascar: Full Report

Fill the Nutrient Gap Madagascar: Full Report October 2016 Photo: WFP/Volana Rarivos World Food Programme Office National de Nutrition Fill the Nutrient Gap Madagascar Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 3 List of Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 9 The Process in Madagascar ................................................................................................................... 10 Malnutrition Characteristics ................................................................................................................. 11 Nutrition-related policies, programmes and regulatory framework .................................................... 22 Availability of Nutritious Foods ............................................................................................................. 27 Access to Nutritious Foods.................................................................................................................... 32 Nutrient Intake ..................................................................................................................................... -

Surveillance and Data for Management (SDM) Project

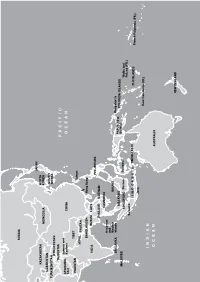

Surveillance and Data for Management (SDM) Project Final Report Submission Date: May 8th, 2020 Revised document submission date: July 31st, 2020 Revised document submission date: December 15th, 2020 Grant No. AID-687-G-13-00003 Submitted by: Institut Pasteur de Madagascar (IPM) BP 1274 Ambatofotsikely, 101 Antananarivo, Madagascar Tel: +261 20 22 412 72 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar. This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Surveillance and Data for Management (SDM) Project Page 1 of 68 Grant No. AID-687-G-13-00003 Institut Pasteur de Madagascar TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 4 PROJECT OVERVIEW/SUMMARY 6 Introduction 7 WP1. MALARIA SURVEILLANCE AND CONTROL MEASURES 8 Subproject SP1: Fever sentinel surveIllance network 8 Subproject SP2: RDT qualIty assurance 10 Subproject SP3: Evaluative research of the fever surveIllance network system 11 Subproject SP4: Fever etiology assessment 12 Subproject SP5: Mathematical models of surveIllance data to detect epIdemIc thresholds 13 Subproject SP6: GIS technology to vIsualIze trends In malarIa IncIdence 15 Subproject SP7 GIS and vector control program to Identify prIorIty areas for Indoor resIdual sprayIng 16 Subproject SP8: AnophelIne mosquIto monItorIng In -

Major Geographic Qualities of South Asia

South Asia Chapter 8, Part 1: pages 402 - 417 Teacher Notes DEFINING THE REALM I. Major geographic qualities of South Asia - Well defined physiography – bordered by mountains, deserts, oceans - Rivers – The Ganges supports most of population for over 10,000 years - World’s 2nd largest population cluster on 3% land mass - Current birth rate will make it 1st in population in a decade - Low income economies, inadequate nutrition and poor health - British imprint is strong – see borders and culture - Monsoons, this cycle sustains life, to alter it would = disaster - Strong cultural regionalism, invading armies and cultures diversified the realm - Hindu, Buddhists, Islam – strong roots in region - India is biggest power in realm, but have trouble with neighbors - Kashmir – dangerous source of friction between 2 nuclear powers II. Defining the Realm Divided along arbitrary lines drawn by England Division occurred in 1947 and many lives were lost This region includes: Pakistan (East & West), India, Bangladesh (1971), Sri Lanka, Maldives Islands Language – English is lingua franca III. Physiographic Regions of South Asia After Russia left Afghanistan Islamic revivalism entered the region Enormous range of ecologies and environment – Himalayas, desert and tropics 1) Monsoons – annual rains that are critical to life in that part of the world 1 2) Regions: A. Northern Highlands – Himalayas, Bhutan, Afghanistan B. River Lowlands – Indus Valley in Pakistan, Ganges Valley in India, Bangladesh C. Southern Plateaus – throughout much of India, a rich -

Measles Outbreak

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Madagascar: Measles Outbreak DREF n°: MDRMG014 / PMG033 Glide n°: Date of issue: 28 March 2019 Expected timeframe: 3 months Operation start date: 28 March 2019 Expected end date: 28 June 2019 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: Yellow IFRC Focal Point: Youcef Ait CHELLOUCHE, Head of Indian National Society focal point: Andoniaina Ocean Islands & Djibouti (IOID) CCST will be project manager Ratsimamanga – Secretary General and overall responsible for planning, implementation, monitoring, reporting and compliance. DREF budget allocated: CHF 89,297 Total number of people affected: 98,415 cases recorded Number of people to be assisted: 1,946,656 people1 in the 10 targeted districts - Direct targets: 524,868 children for immunization - Indirect targets: 1,421,788 for sensitization Host National Society presence of volunteers: Malagasy red Cross Society (MRCS) with 12,000 volunteers across the country. Some 1,030 volunteers 206 NDRT/BDRTs, 10 full-time staff will be mobilized through the DREF in the 10 districts Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), German Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, Luxembourg Red Cross, French Red Cross through the Indian Ocean Regional Intervention Platform (PIROI). Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Ministry of Health, WHO, UNICEF. A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster Measles, a highly contagious viral disease, remains a leading cause of death amongst young children around the world, despite the availability of an effective vaccine. -

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

Albania's 'Sworn Virgins'

THE LINGUISTIC EXPRESSION OF GENDER IDENTITY: ALBANIA’S ‘SWORN VIRGINS’ CARLY DICKERSON A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN LINGUISTICS YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2015 © Carly Dickerson, 2015 Abstract This paper studies the linguistic tools employed in the construction of masculine identities by burrneshat (‘sworn virgins’) in northern Albania: biological females who have become ‘social men’. Unlike other documented ‘third genders’ (Kulick 1999), burrneshat are not motivated by considerations of personal identity or sexual desire, but rather by the need to fulfill patriarchal roles within a traditional social code that views women as property. Burrneshat are thus seen as honourable and self-sacrificing, are accepted as men in their community, and are treated accordingly, except that they do not marry or engage in sexual relationships. Given these unique circumstances, how do the burrneshat construct and express their identity linguistically, and how do others within the community engage with this identity? Analysis of the choices of grammatical gender in the speech of burrneshat and others in their communities indicates both inter- and intra-speaker variation that is linked to gendered ideologies. ii Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………….. ii Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………………………….. iii List of Tables …………………………………………………………………………..……… viii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………………ix Chapter One – Introduction ……………………………………………………………………... 1 Chapter Two – Albanian People and Language ………………………………………………… 6 2.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………6 2.1 History of Albania ………………………………………………………………………..6 2.1.1 Geographical Location ……………………………………………………………..6 2.1.2 Illyrian Roots ……………………………………………………………………….7 2.1.3 A History of Occupations …………………………………………………………. 8 2.1.4 Northern Albania …………………………………………………………………. -

Myzopodidae: Chiroptera) from Western Madagascar

ARTICLE IN PRESS www.elsevier.de/mambio Original investigation The description of a new species of Myzopoda (Myzopodidae: Chiroptera) from western Madagascar By S.M. Goodman, F. Rakotondraparany and A. Kofoky Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, USA and WWF, Antananarivo, De´partement de Biologie Animale, Universite´ d’Antananarivo, Antananarivo, Madagasikara Voakajy, Antananarivo, Madagascar Receipt of Ms. 6.2.2006 Acceptance of Ms. 2.8.2006 Abstract A new species of Myzopoda (Myzopodidae), an endemic family to Madagascar that was previously considered to be monospecific, is described. This new species, M. schliemanni, occurs in the dry western forests of the island and is notably different in pelage coloration, external measurements and cranial characters from M. aurita, the previously described species, from the humid eastern forests. Aspects of the biogeography of Myzopoda and its apparent close association with the plant Ravenala madagascariensis (Family Strelitziaceae) are discussed in light of possible speciation mechanisms that gave rise to eastern and western species. r 2006 Deutsche Gesellschaft fu¨r Sa¨ugetierkunde. Published by Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved. Key words: Myzopoda, Madagascar, new species, biogeography Introduction Recent research on the mammal fauna of speciation molecular studies have been very Madagascar has and continues to reveal informative to resolve questions of species remarkable discoveries. A considerable num- limits (e.g., Olson et al. 2004; Yoder et al. ber of new small mammal and primate 2005). The bat fauna of the island is no species have been described in recent years exception – until a decade ago these animals (Goodman et al. 2003), and numerous remained largely under studied and ongoing other mammals, known to taxonomists, surveys and taxonomic work have revealed await formal description. -

DOWNLOAD 1 IPC Madagascar Acutefi

INTEGRATED FOOD SECURITY PHASE CLASSIFICATION Current situation: March-May 2017 Projected situation: June-September 2017 REPUBLIC OF MADAGASCAR IPC analysis conducted from 8 to 15 June for the Southern and South eastern of Madagascar KEY HIGHLIGHTS ON THE FOOD INSECURITY FROM MARCH TO MAY 2017 % POPULATION REQUIRING URGENT ACTION Percentage (1) of households and number of people requiring Districts in emergency phase despite humanitarian actions (IPC Phase 3 !): Betioky, urgent action to protect their livelihoods and reduce food Ampanihy, Tsihombe, Beloha, Amboasary Sud; four communes in the district of consumption gaps from March and April 2017, in the areas Taolagnaro (Ranopiso, Analapatsy, Andranobory, Ankariera) and the commune of affected by disasters (drought/floods) in the South and South Beheloka in Tuléar II eastern districts of Madagascar and in comparison with the Districts in crisis phase (IPC Phase 3): Vangaindrano, Farafanagana, Vohipeno situation in last 2016. Districts in crisis phase despite humanitarian actions (IPC Phase 2!): Ambovombe and Bekily. Evolution 2017 rate march to (base 100 In total, 9% of the population (about 262,800 people) are in emergency phase (IPC District 2016 may year 2016) MANAKARA 73 395 0 phase 4) and 27% (about 804,600 people) are classified in crisis phase (IPC phase 3). VOHIPENO 93 490 0 FARAFANGANA 152 575 0 Food consumption: In the South eastern regions of the country, about 18% of VANGAINDRANO 165 497 0 South eastern 484 957 0% households have a poor food consumption score against 33% in the South. Vohipeno, BETIOKY+TULEAR II 76 751 132 761 173,0% AMPANIHY 168 000 103 528 61,6% Tsihombe districts and the commune of Beheloka (Tuléar II) have critical food BELOHA 88 856 54 752 61,6% consumption score, above 40%.