Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Affairs Record

1996 January Volume No XLII No 1 1995 CONTENTS Foreign Affairs Record VOL XLII NO 1 January, 1996 CONTENTS BRAZIL Visit of His Excellency Dr. Fernando Henrique Cardoso, President of the Federative Republic of Brazil to India 1 External Affairs Minister of India called on President of the Federative Republic of Brazil 1 Prime Minister of India met the President of Brazil 2 CAMBODIA External Affairs Minister's visit to Cambodia 3 Visit to India by First Prime Minister of Cambodia 4 Visit of First Prime Minister of Cambodia H.R.H. Samdech Krom Preah 4 CANADA Visit of Canadian Prime Minister to India 5 Joint Statement 6 FRANCE Condolence Message from the President of India to President of France on the Passing away of the former President of France 7 Condolence Message from the Prime Minister of India to President of France on the Passing away of the Former President of France 7 INDIA Agreement signed between India and Pakistan on the Prohibition of attack against Nuclear Installations and facilities 8 Nomination of Dr. (Smt.) Najma Heptullah, Deputy Chairman, Rajya Sabha by UNDP to serve as a Distinguished Human Development Ambassador 8 Second Meeting of the India-Uganda Joint Committee 9 Visit of Secretary General of Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to India 10 IRAN Visit of Foreign Minister of Iran to India 10 LAOS External Affairs Minister's visit to Laos 11 NEPAL Visit of External Affairs Minister to Nepal 13 OFFICIAL SPOKESMAN'S STATEMENTS Discussion on Political and Economic Deve- lopments in the region -

India Recent Split Among Various Hindu Extremist Parties Leads One to Think About Future of Extremism in Indian Politics

Report # 95 & 96 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD East Asia, Central Asia, GCC, FC, China & Turkey Nadia Tasleem Weekly Report from 21 November 2009 to 4 December 2009 Presentation: 10 December 2009 This report is based on the review of news items focusing on political, economic, social and geo-strategic developments in various regions namely; East Asia, Central Asia, GCC, FC, China and Turkey from 21 November 2009 to 20 December 2009 as have been collected by interns. Prelude to Summary: This report tries to highlight major issues being confronted by various Asian states at political, geo-strategic, social and economic front. On one hand this information helps one to build deep understanding of these regions. It gives a clear picture of ongoing pattern of developments in various states hence leads one to find similarities and differences amid diverse issues. On the other hand thorough and deep analysis compels reader to raise a range of questions hence provides one with an opportunity to explore more. Few such questions that have already been pointed out would be discussed below. To begin with India recent split among various Hindu extremist parties leads one to think about future of extremism in Indian politics. Recently released Liberhan Commission Report has convicted BJP and other extremists for their involvement in demolition of Babri Mosque 17 years ago. In response to this report BJP has out rightly denied their involvement rather has condemned government for her efforts to shatter BJP’s image. An undeniable fact however remains that L.K. Advani; one of the key members of BJP had been an active participant in Ayodhya movement. -

Induction Material

INDUCTION MATERIAL GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF FINANCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 2013 (Eleventh Edition: 11th September, 2013) Preface to the 11th Edition The Department of Pension and Administrative Reforms had issued instructions in 1978 that each Ministry/Department should prepare an Induction Material setting out the aims and objects of the Department, detailed functions of the various divisions and their inter-relationship which would be useful for the officers of the Ministry/Department particularly the new entrants. In pursuance to this, Department of Economic Affairs has been bringing out ‘Induction Material’ since 1981. The present Edition is Eleventh in the series. 2. Department of Economic Affairs is the nodal agency of the Government of India for formulation of economic policies and programmes. In the present day context of global economic slowdown, the role of the Department of Economic Affairs has assumed a special significance. An attempt has been made to delineate the activities of the Department in a manner that would help the reader accurately appreciate its role. 3. The Induction Material sets out to unfold the working of the Department up to the level of the Primary Functional Units, i.e. Sections. All members of the team should find it useful to identify those concerned with any particular item of work right upto the level of Section Officer. The other Ministries and Departments will also find it useful in identifying the division or the officer to whom the papers are to be addressed. 4. I hope that all users will find this edition of Induction Material a handy and useful guide to the functioning of the Department of Economic Affairs. -

SBI Associate PO GK Digest

SBI Associate PO GK Digest www.BankExamsToday.com SBI Associate PO GK Digest By – Ramandeep Singh Ramandeep Singh 11/10/2014 SBI AssociateRBI Policy PO Rates GK Digest Bank Rate : 9.0% Repo Rate : 8.0% Reverse Repo Rate : 7.0% Marginal Standing Facility Rate : 9.0% CRR : 4% SLR : 22% Important Indian Organizations and their Heads List of important organization India and their heads. This list is very important for all banking exams. Sr Head Organization 1. Mohd.Hamid Ansari Chairman, Rajya Sabha 2. Sumitra Mahajan Chairperson of Lok Sabha 3. Narendra D Modi Chairman, Planning Commission 4. Gulam Nabi Azad Leader of Opposition in Rajya Sabha 5. Narendra D Modi Leader of House in Lok Sabha 6. Mallikarjun Kharge Leader of Congress in Lok Sabha 7. V. Sampath Chief Election Commissioner 8. Syed Nasim Ahmed Zaidi Election Commissioner 9. Harisanker Brahma Election Commissioner 10. Pradeep Kumar Chief Vigilance Commissioner 11. Sujatha Singh Foreign Secretary 12. Shashi Kant Verma Comptroller & Auditor General of India 13. Jus. Vangala Eswaraiah Chairman, National Commission for Backward Classes 14. Rahul Khullar Chairman, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India 15. Ranjit Sinha CBI Director 16. Rameshwar Oran Chairman, National Commission for Scheduled Tribes 17. Naseem Ahmed Chairperson, National Commission for Minorities 18. Rajni Razdan Chairman, UPSC 19. Sharad Kumar Director General, National Investigation Agency 20. Ved Prakash Chairman, UGC 21. K. Radhakrishnan Chairman, Space Commission and ISRO 22. R.K. Sinha Chairman, Atomic Energy Commission and Sec. Deptt. of Atomic Energy 23. A. Bhattacharya Chairman, SSC 24. K.G. Balakrishnan Chairman, Human Rights Commission 25. -

NKC) Is Pleased and Aspirations of Domain Experts and Other Concerned to Submit Its final Report to the Nation

National Knowledge Commission Report to the Nation 2006 - 2009 Government of India © National Knowledge Commission, March 2009 Published by: National Knowledge Commission Government of India Dharma Marg, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi-110 021 www.knowledgecommission.gov.in Copy editing, design and printing: New Concept Information Systems Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi-110 076 www.newconceptinfo.com Foreword The National Knowledge Commission (NKC) is pleased and aspirations of domain experts and other concerned to submit its final Report to the Nation. It is essentially stakeholders. a compilation of our various reports from 2006 to 2009. The Commission was set up by the Prime Minister In the last three years NKC has submitted around Dr. Manmohan Singh to prepare a blueprint to tap 300 recommendations on 27 subjects in the form of into the enormous reservoir of our knowledge base so letters to the Prime Minister. These have been widely that our people can confidently face the challenges of disseminated in our Reports to the Nation, seminars, the 21st century. We were conscious that this was a conferences, discussions and covered by national and daunting task, which required not only resources and regional media. These recommendations are also time, but also a bold vision and a long-term focus on accessible through the NKC website in 10 languages. speedy implementation. As part of our outreach program we have organised various conferences and workshops in collaboration At the heart of NKC’s mandate are five key areas with universities, colleges, schools, CII, FICCI, AIMA, related to ACCESS, CONCEPTS, CREATION, and others. We have also been reaching out to various APPLICATIONS and SERVICES. -

Van Was at the Chinese Embassy Gate and These "Hbetans Were Put On

525 Statement by Minister AGRAHAYANA 26,1913 (SAKA)Statement by Minister 526 Reported Scuffle on 11.12.91 between Arrest of Shnfndr^tOup&LkU3. & aJoumaSst and a police officer and the others si C^andSajhon16. li.91 Arrest of some tibetan girls in New Delhi on 15.12.91 comprised 17 women and one man. A police surety by 3.00 p.m. of 14th December, 1991. van was at the Chinese Embassy Gate and Thirdly, as regards the rest they were to be these "Hbetans were put on the vehicle. One released on furnishing a personal bond of girl, about 20 years’ old, suddenly jumped the amount of Rs. 5V000 and surety of Rs. off from the van and started running away 2000/-. The Supreme Court further passed shouting slogans. She was over-powered orders thatthe persons released would abide and again put back into the vehicle. Since by law and would not commit breach of the the body of the vehicle was filled with the peace or violate orders under section 144 of Tibetans and policeman, including two lady the code of Criminal Procedure. The Delhi Constables, this girt was put in the driver's Police have reported that all the arrested cabin alongwith a Sub-Inspector of Po&ce persons have been released in accordance and a Constable. They were thetLtaken to with the dfrections of the Supreme Court the Chankaya-puri Police Statioflfevhich is about 200 meters away. The Tfcetans were violent and were shouting slogans. When the van was going to enter the police station, 16.32/1/2 hra. -

The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years : an Overview

1 2 The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years : An Overview 3 Published by : The Indian Law Institute (West Bengal State Unit) iliwbsu.in Printed by : Ashutosh Lithographic Co. 13, Chidam Mudi Lane Kolkata 700 006 ebook published by : Indic House Pvt. Ltd. 1B, Raja Kalikrishna Lane Kolkata 700 005 www.indichouse.com Special Thanks are due to the Hon'ble Justice Indira Banerjee, Treasurer, Indian Law Institute (WBSU); Mr. Dipak Deb, Barrister-at-Law & Sr. Advocate, Director, ILI (WBSU); Capt. Pallav Banerjee, Advocate, Secretary, ILI (WBSU); and Mr. Pradip Kumar Ghosh, Advocate, without whose supportive and stimulating guidance the ebook would not have been possible. Indira Banerjee J. Dipak Deb Pallav Banerjee Pradip Kumar Ghosh 4 The High Court at Calcutta 150 Years: An Overview तदॆततत- क्षत्रस्थ क्षत्रैयद क्षत्र यद्धर्म: ।`& 1B: । 1Bद्धर्म:1Bत्पटैनास्ति।`抜֘टै`抜֘$100 नास्ति ।`抜֘$100000000स्ति`抜֘$1000000000000स्थक्षत्रैयदत । तस्थ क्षत्रै यदर्म:।`& 1Bण । ᄡC:\Users\सत धर्म:" ।`&ﲧ1Bशैसतेधर्मेण।h अय अभलीयान् भलीयौसमाशयनास्ति।`抜֘$100000000 भलीयान् भलीयौसमाशयसर्म: ।`& य राज्ञाज्ञा एवम एवर्म: ।`& 1B ।। Law is the King of Kings, far more powerful and rigid than they; nothing can be mightier than Law, by whose aid, as by that of the highest monarch, even the weak may prevail over the strong. Brihadaranyakopanishad 1-4.14 5 Copyright © 2012 All rights reserved by the individual authors of the works. All rights in the compilation with the Members of the Editorial Board. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holders. -

Caste, Society and Politics of North Bengal, 1869-1977

Caste, Society and Politics of North Bengal, 1869-1977 Thesis Submitted to the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, West Bengal, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Papiya Dutta Assistant Professor Syamsundar College Shyamsundar, Burdwan Supervisor Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh Department of History University of North Bengal Raja Rammohanpur, Darjeeling West Bengal: 734013 University of North Bengal 2011 31 JAN 2013 R 9 54· 14 J) 91 9c_, ·~ Acknowledgement In the present work I have tried to analyze the nature of caste society of North Bengal and its distinctiveness from other parts of Bengal nay India. It also seeks to examine the changing process of caste solidarity and caste politics of the region concerned. I have also tried to find out the root of the problem of the region from historical point of view. I have been fortunate enough to get professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh as my supervisor who despite his busy schedule in academic and socio-cultural assignments and responsibilities have provided ·his invaluable and persistent guidance and directed me over the last five years by providing adequate source materials. I express my sincere gratitude for his active supervision and constant encouragement, advice throughout the course of my research work. In this work I have accumulated debts of many people and institutions and I am grateful to all of them. I am grateful to the learned scholars, academicians and authors whose work I have extremely consulted during the course of my study. This work could not have been possible without the co-operation of a large number of people from various fields. -

![6. the Planning Commission Is : [UP PCS 1994] (A) a Ministry (B) a Government Department (C) an Advisory Body (D) an Autonomous Corporation Ans: (C) 7](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5373/6-the-planning-commission-is-up-pcs-1994-a-a-ministry-b-a-government-department-c-an-advisory-body-d-an-autonomous-corporation-ans-c-7-5005373.webp)

6. the Planning Commission Is : [UP PCS 1994] (A) a Ministry (B) a Government Department (C) an Advisory Body (D) an Autonomous Corporation Ans: (C) 7

INDIAN ECONOMY Objective Applicable For All Competitive Exams Sure Questions ________________________________ © Copyright reserved ________________________________ Contents Click the below headings for fast travel ________________________________ QUESTIONS WITH ANSWERS Fundamentals of Indian Economy and Planning Poverty, Unemployment and Alleviation Programmes Currency and Inflation Indian Banking System and Capital Market Fiscal System of India Industries, Infrastructure and Foreign Trade International Organisations and Human Development Natural Resources and Other Facts of Indian Economy QUESTIONS WITH ANSWERS _____________________ Fundamentals of Indian Economy and Planning _____________________ 1. National Development Council was set up in: (a) 1948 (b) 1950 (c) 1951 (d) 1952 Ans: (d) 2. Economic Planning is a subject: [Asstt Grade 1991] (a) in the Union List (b) in the State List (c) in the Concurrent List (d) unspecified in any special list Ans: (a) 3. For internal financing of Five Year Plans, the government depends on: [NDA 1991] (a) taxation only (b) taxation and public borrowing (c) public borrowing and deficit financing (d) taxation, public borrowing and deficit financing Ans: (a) 4. The National Development Council gets its administrative support from: (a) Planning Commission (b) Finance Commission (c) Administrative Reforms Commission (d) Sarkaria Commission Ans: (a) 5. The Five Year Plans of India intend to develop the country industrially through: [NDA 1991] (a) the public sector (b) the private sector (c) the public, private, -

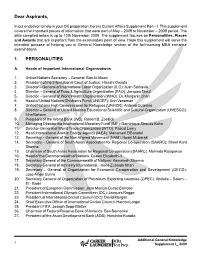

Additional General Knowledge Supplement I 2009

Dear Aspirants, In our endeavor to help in your GK preparation, here is Current Affairs Supplement Part – I. This supplement covers the important pieces of information that were part of May – 2009 to November – 2009 period. The data compiled below is up to 10th November 2009. The supplement focuses on Personalities, Places and Awards that are important from the examination point of view. Hope this supplement will serve the intended purpose of helping you in General Knowledge section of the forthcoming MBA entrance examinations. 1. PERSONALITIES A. Heads of Important International Organizations 1. United Nations Secretary – General: Ban-ki-Moon 2. President of the International Court of Justice: Hisashi Owada 3. Director – General of International Labor Organization (ILO): Juan Somavia 4. Director – General of Food & Agriculture Organization (FAO): Jacques Diouf 5. Director – General of World Health Organization (WHO): Dr. Margaret Chan 6. Head of United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): Ann Veneman 7. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): Antonio Guterres 8. Director – General of United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Irina Bokova 9. President of the World Bank (WB): Robert B. Zoellick 10. Managing Director the International Monetary Fund (IMF): Dominique Strauss Kahn 11. Director-General of World Trade Organization (WTO): Pascal Lamy 12. Head International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA): Mohamed ElBaradei 13. Secretary – General of the Non Aligned Movement (NAM): Hosni Mubarak 14. Secretary – General of South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC): Sheel Kant Sharma 15. Chairman of South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC): Mahinda Rajapaksa 16. Head of the Commonwealth of Nations: Queen Elizabeth-II 17. -

LOK SABRA DEBATES (English Version)

NIta' .. ~. V.I. I, No 1 MODay, t Dec.mh«J18. 1989 Agraha)a.. 27. 1911 (Sata) LOK SABRA DEBATES (English Version) First SessiOD (Ninth Lok Sabba) (VoJ I contains NOl. I to ~) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELW Price I B.s. 6.00 [O&lonw., BNOLIIB Pl.OCJ!mlMOS lJiCLUDD IN 1bI0LIIII V..... AND OMOIMAL Hnml PaOCBBOINOlINCLUDm Df HINDI VDJICBf WILL • 1'UATID AS AUTIIGJUT4TfQ AlII) HOT TBB TRANlL.\TlOli 'I'B8IUIOI'.] CONTENTS [Ninth Series, Vol I, First Session, 198911911 (Saka)] No.1, Monday, December 18, 1989/Agrahayana 27, 1911 (Saka) COLUMNS Observance of Silence 1-2 List of Members Elected to Lok Sabha -Laid on the Table 2-47 Panel of Chairmen 47 Resignation by Members 47-48 Members Sworn 49-70 LOKSABHA The Speaker * Shri Rabi Ray The Deputy Speaker (Vacant) Panel of Chairmen ** Shri Vakkom Purushothaman Dr. Thambi Durai Shri Satya Pal Malik Shri Jaswant Singh Shri Nirmal Chatterjee Shrimati Gaeta 'Mukherjee Secretary-General Dr. Subhash C. Kashyap ~t 1989 er 20,198' GOVERNME:NT OF INDIA MEMBERS OF THE CABINET Prime Minister and also Shri Vishwanath Pratap Singh incharge of the Ministries/ Departments of Defence; Personnel; Public Grievances and Pensions; Science & Technology; Atomic Energy; Electronics; Ocean Development: Space; Environment & Forests and other subjects not allocated to any other Cabinet Minister or Minister of State (Independent charge). Deputy Prime Minister Shri Devi Lal and Minister of Agriculture Minister of Finance Prof. Madhu Dandavate Minister of Railways Shri George Fernandes Minister of Industry Shri Ajit Singh Minister of T extifes with Shri Sharad Yadav additional charge of the Ministry of Food Processing Industries Minister of Home Affairs Shri Mufti Mohammad Sayeed Minister of Com merce and Shri Arun Kumar Nehru Tourism Minister of Energy with Shri Arif Mohd. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES Version)

tN'.... SerIe!, Vel. II, No.2 TaeIcJa)" Mardi 13, U90 PIIaJ_ 22, 1911 (SU.) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Seeond Session (Ninth Lok Sabb.) (YoJ. II coattda NOl. J to 10) LOK SABIU SEClRDAlUA'J NEW DELHI P"", •. 6.oo [OaJODIAL IbIouIII P&OCIIIDIROS nta.UDD III BJIIOLIIB V.... AND ORIGIRAL HINDI PUCllllDINOI IMCLUDID Of HINDI VIUIOII WILL • TUA'rID AS AUTIDUI'ATJVB AJU) wor ,.. ftANlLAna. "_"'.1 CONTENTS [Ninth Series, Vol II, Second Session, 199011911 (Saka)] No.2, Tuesday, March 13, 1990IPhaiguna 22, 1911 (Saka) CoLUMNS Motion under Rule 388 1--4 Re: Suspension of Questions Hour 'itten Answers to Questions: 4-284 Starred Question Nos. 1 to 20 4-23 Unstarred Question Nos. 1 to 126, 128, 129 23-284 and 131 to 231 Motion under Rule 342 285-376 Situation in Jammu and Kashmir 384-464 Shri Mufti Mohammad Sayeed 285-292 448--458 Shri Vasant Sathe 298-307 Shri Jaswant Singh 309-319 Shri M.J. Akbar 319-333 Shri Saifuddin Choudhury 333-339 Shri K.C. Tyagi 340--344 Shri Kamal Nath 344-349 Shri Indrajit Gupta 349-360 Shri Piyare Lal Handoo 360-371 Shri Vishwanath Pratap Singh 372-376 Shri Balgopal Mishra 385-386 Shri Kadambur M.R. Janardhanan 38~88 Shri George Fernandes 388-404 (Ii) CoLUMNS Shri Arif Baig 404-407 Shri H.K.L. Bhagat 407-414 Shri Nani Bhattacharya 414-415 Shri Rajiv Gandhi 415-434 Shri Sultan Salah uddin Owaisi 434-436 Shri Ibrahim Sulaiman Sait 436-440 Shri Ram Krishna Yadav 441-442 Shri Inder Jit 442-444 Shri Vamanrao Mahadik 444-445 Shri Rameshwar Prasad 445-446 Shri P.C.