Ghosts of Chinas Past and Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

A Brief Analysis of China's Contemporary Swordsmen Film

ISSN 1923-0176 [Print] Studies in Sociology of Science ISSN 1923-0184 [Online] Vol. 5, No. 4, 2014, pp. 140-143 www.cscanada.net DOI: 10.3968/5991 www.cscanada.org A Brief Analysis of China’s Contemporary Swordsmen Film ZHU Taoran[a],* ; LIU Fan[b] [a]Postgraduate, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, effects and packaging have made today’s swordsmen China. films directed by the well-known directors enjoy more [b]Associate Professor, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, China. personalized and unique styles. The concept and type of *Corresponding author. “Swordsmen” begin to be deconstructed and restructured, and the swordsmen films directed in the modern times Received 24 August 2014; accepted 10 November 2014 give us a wide variety of possibilities and ways out. No Published online 26 November 2014 matter what way does the directors use to interpret the swordsmen film in their hearts, it injects passion and Abstract vitality to China’s swordsmen film. “Chivalry, Military force, and Emotion” are not the only symbols of the traditional swordsmen film, and heroes are not omnipotent and perfect persons any more. The current 1. TSUI HARK’S IMAGINARY Chinese swordsmen film could best showcase this point, and is undergoing criticism and deconstruction. We can SWORDSMEN FILM see that a large number of Chinese directors such as Tsui Tsui Hark is a director who advocates whimsy thoughts Hark, Peter Chan, Xu Haofeng , and Wong Kar-Wai began and ridiculous ideas. He is always engaged in studying to re-examine the aesthetics and culture of swordsmen new film technology, indulging in creating new images and film after the wave of “historic costume blockbuster” in new forms of film, and continuing to provide audiences the mainland China. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

DP TRIANGLE.Indd

DISTRIBUTION WILD SIDE FILMS 42, rue de Clichy 75009 Paris Tél : 01 42 25 82 00 Fax : 01 42 25 82 10 www.wildside.fr RELATIONS PRESSE LE PUBLIC SYSTEME CINEMA Céline Petit & Annelise Landureau 40, rue Anatole France 92594 Levallois-Perret cedex Tel : 01 41 34 23 50 / 22 01 Fax : 01 41 34 20 77 [email protected] [email protected] www.lepublicsystemecinema.com www.triangle-lefi lm.com CADAVRE EXQUIS : Jeu créé par les surréalistes en 1920 qui consiste à faire composer une phrase, ou un dessin, par plusieurs personnes sans qu’aucune d’elles puisse tenir compte de la collaboration ou des collaborations précédentes. En règle générale un cadavre exquis est une histoire commencée par une personne et terminée par plusieurs autres. Quelqu’un écrit plusieurs lignes puis donne le texte à une autre personne qui ajoute quelques lignes et ainsi de suite jusqu’à ce que quelqu’un décide de conclure l’histoire. DISTRIBUTION STOCK Wild Side Films Distribution Service Tél : 01 42 25 82 00 STOCKS COPIES ET PUBLICITÉ Fax : 01 42 25 82 10 Grande Région Ile-de-France www.wildside.fr 24, Route de Groslay 95204 Sarcelles WILD SIDE FILMS DIRECTION DE LA DISTRIBUTION présente Marc-Antoine Pineau COPIES Tél. : 01 34 29 44 21 [email protected] Fax : 01 39 94 11 48 [email protected] Dossier de presse imprimé en papier recyclé PROGRAMMATION Philippe Lux PUBLICITÉ [email protected] Tél. : 01 34 29 44 26 Fax : 01 34 29 44 09 [email protected] MÉDIAS Le premier film réalisé sur le principe du jeu du cadavre exquis Christophe Laduche par les trois maîtres du cinéma de Hong Kong [email protected] LYON 25, avenue Beauregard 69150 Decines DIRECTRICE TECHNIQUE 35MM Brigitte Dutray Tél. -

The Linguistic Categorization of Deictic Direction in Chinese – with Reference to Japanese – Christine Lamarre

The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese – With reference to Japanese – Christine Lamarre To cite this version: Christine Lamarre. The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese – With reference to Japanese –. Dan XU. Space in Languages of China, Springer, pp.69-97, 2008, 978-1-4020-8320-4. hal-01382316 HAL Id: hal-01382316 https://hal-inalco.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01382316 Submitted on 16 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Lamarre, Christine. 2008. The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese — With reference to Japanese. In Dan XU (ed.) Space in languages of China: Cross-linguistic, synchronic and diachronic perspectives. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York: Springer, pp.69-97. THE LINGUISTIC CATEGORIZATION OF DEICTIC DIRECTION IN CHINESE —— WITH REFERENCE TO JAPANESE —— Christine Lamarre, University of Tokyo Abstract This paper discusses the linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Mandarin Chinese, with reference to Japanese. It focuses on the following question: to what extent should the prevalent bimorphemic (nondeictic + deictic) structure of Chinese directionals be linked to its typological features as a satellite-framed language? We know from other satellite-framed languages such as English, Hungarian, and Russian that this feature is not necessarily directly connected to satellite-framed patterns. -

Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow

CJ7 Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP Public Relations Block Korenbrot PR Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Judy Chang Leila Guenancia 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-247-2948 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 1 Short Synopsis: From Stephen Chow, the director and star of Kung Fu Hustle, comes CJ7, a new comedy featuring Chow’s trademark slapstick antics. Ti (Stephen Chow) is a poor father who works all day, everyday at a construction site to make sure his son Dicky Chow (Xu Jian) can attend an elite private school. Despite his father’s good intentions to give his son the opportunities he never had, Dicky, with his dirty and tattered clothes and none of the “cool” toys stands out from his schoolmates like a sore thumb. Ti can’t afford to buy Dicky any expensive toys and goes to the best place he knows to get new stuff for Dicky – the junk yard! While out “shopping” for a new toy for his son, Ti finds a mysterious orb and brings it home for Dicky to play with. To his surprise and disbelief, the orb reveals itself to Dicky as a bizarre “pet” with extraordinary powers. Armed with his “CJ7” Dicky seizes this chance to overcome his poor background and shabby clothes and impress his fellow schoolmates for the first time in his life. -

Chungking Express.Pdf

Chungking Express BEFORE VIEWING – BEFORE READING SYNOPSIS TASK ■ With a partner, discuss and record your expectations of a film called Chungking Express which has been made in Hong Kong. After viewing the film you should compare notes with your partner to see how many of your expectations have been confirmed or contradicted. SYNOPSIS Cult Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express is a stylish combination of romance, dead-pan comedy and film noir set in and around Hong Kong’s notorious Chunking Mansions, a complex of shabby hostels, bars and clubs teaming with illegal immigrants. The story centres on a small takeaway stall, the Midnight Express, which is frequented by two lovelorn Cops (223, Takeshi Kaneshiro and 633, Tony Leung Chiu Wai). They become involved with a mysterious drug dealer dressed in a blonde wig and sunglasses (Brigitte Lin), on the run from drug traffickers, and an impulsive young dreamer (Faye Wong) who works behind the counter of the Midnight Express. The central concerns of the film are identity and our reluctance to show, or to accept, who we truly are. The Brigitte Lin character wears a wig and sunglasses to hide her true self. Cop 223 refuses to accept the fact that his girlfriend has left him. The waitress (Faye Wong) secretly cleans the apartment for Cop 633 who avoids reading a goodbye note from his ex- girlfriend and is unable to realise that his apartment is getting cleaner and cleaner. BACKGROUND FOR WONG KAR WAI Wong Kar Wai belongs to the mid-1980s Second New Wave of Hong Kong filmmakers who continued to develop the innovative approaches initiated by the original Hong Kong New Wave, which included directors such as Tsui Hark, Ann Hui and Patrick Tam. -

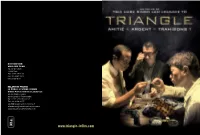

Tsui Hark Ringo Lam Johnnie To

TSUI HARK LOUIS KOO A legendary producer and director, Tsui Hark is one of Hong Kong cinema’s most influential figures. A pioneer of the 80’s Hong Kong New — AH FAI Wave film movement, Tsui Hark immediately caught the attention of critics with his innovative style and techniques. “Butterfly Murders” Singer, actor, model – Louis Koo is one of Hong Kong’s most popular Chanteur, acteur, mannequin – Louis Koo est l’une des plus grandes (1979) and “Dangerous Encounters: 1st Kind”(1980) pushed the boundary of Hong Kong genre films as well as the limit of the censors. celebrities. He began his film career in the mid-90’s and has acted in stars de Hong Kong. Il commence sa carrière au milieu des années 90 Following the creation of Film Workshop in 1984, he directed and produced a series of successful commercial films that initiated the so-called over 40 movies such as Wilson Yip’s “Bullet Over Summer”(1999), Tsui et joue dans plus de 40 films, dont « Bullets Over Summer » (1999) de “golden era” of Hong Kong cinema. Films including “A Chinese Ghost Story”(1987), “Swordsman”(1990), and “Once Upon A Time In China” Hark’s “Legend of Zu 2”(2001) and Derek Yee’s “Lost In Time”(2003). Wilson Yip, « La Légende de Zu 2 » (2001) de Tsui Hark et « Lost In (1991) established Tsui Hark's dominance across Asia. After directing two films in Hollywood, he returned to Hong Kong in the mid-90’s Over the past couple of years, he has forged a close working relationship Time » (2003) de Derek Yee. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Aesthetics, Representation, Circulation Man-Fung Yip Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2017 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. An earlier version of Chapter 2 “In the Realm of the Senses” was published as “In the Realm of the Senses: Sensory Realism, Speed, and Hong Kong Martial Arts Cinema,” Cinema Journal 53 (4): 76–97. Copyright © 2014 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments viii Notes on Transliteration x Introduction: Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity 1 1. Body Semiotics 24 2. In the Realm of the Senses 56 3. Myth and Masculinity 85 4. Th e Diffi culty of Diff erence 115 5. Marginal Cinema, Minor Transnationalism 145 Epilogue 186 Filmography 197 Bibliography 203 Index 215 Introduction Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Made at a time when confi dence was dwindling in Hong Kong due to a battered economy and in the aft ermath of the SARS epidemic outbreak,1 Kung Fu Hustle (Gongfu, 2004), the highly acclaimed action comedy by Stephen Chow, can be seen as an attempt to revitalize the positive energy and tenacious resolve—what is commonly referred to as the “Hong Kong spirit” (Xianggang jingshen)—that has allegedly pro- pelled the city’s amazing socioeconomic growth. -

The Ghost of Liaozhai: Pu Songling's Ghostlore and Its History of Reception

THE GHOST OF LIAOZHAI: PU SONGLING’S GHOSTLORE AND ITS HISTORY OF RECEPTION Luo Hui A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Hui Luo, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58980-9 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58980-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.