Essay Battling Academic Corruption in Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr-Eton-Marus-CV.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME Eton Marus (PhD) DATE OF BIRTH Septembers 28th 1978 ADDRESS Kabale University, Uganda Box 317 Kabale 256772880149/256701304416 [email protected]/[email protected] PROFESSIONAL Finance/Accounts, Business, Marketing and Monitoring and Evaluation AREAS ACADEMIC YEARS INSTITUTION QUALIFICATIONS QUALIFICATIONS 2015-2018 Nkumba University PhD Business Administration (Finance) 2016-2017 Uganda Management Post Graduate Diploma In Institute-Kampala Monitoring and Evaluation 2010-2012 Cavendish University Masters in Business Administration 2009-2010 Gulu University Post Graduate Diploma in Financial Management 2002-2006 Makerere University Bachelor of Commerce 1998-2001 Makerere University Higher Diploma In Business School Marketing OTHER Grant and Proposal Writing and Management. (ACRA) Mbarara TRAININGS University of Science and Technology July 2019 Programme Skills Development (Assessing Academic and Professional Programmes, Uganda National Council of Higher Education, Kampala 2019. Researcher Connect Professional Development for Researchers (Proposal writings skills, Resource mobilization, Academic Collaborations, Networking, Grants Management and Persuasive Proposal writing. British Council Kampala 2019. Post Graduate Certificate in Monitoring and Evaluation, Makerere University 2014. Post Graduate Certificate in Administrative Law Makerere University 2013 Post Graduate Certificate in Procurement and Contract Management Uganda Management Institute-Kampala 2013 Post Graduate Certificate in Training of Trainers, -

Govt Takes Over Running of Busoga University

12 NEW VISION, Tuesday, February 6, 2018 REGIONAL NEWS Govt takes over running of Busoga University Amuru leaders clash KAMULI Authorities in Amuru have By Tom Gwebayanga National Forest Authority (NFA) over a planned re-opening of the The Government has announced boundaries of Olwal Central Forest its decision to take over the Reserve. Olwal Forest Reserve is management of the stressed private located in Olwal village, Giragira Busoga University in a bid to end parish, Lamogi sub-county in Amuru the woes that have rocked the district. It covers 1,384 hectares institution for over six years, the of land. The leaders, who included Speaker of Parliament, Rebecca Kilak South MP Gilbert Olanya Kadaga, has said. and Amuru LC5 chairman Michael Kadaga said President Yoweri Lakony, demanded that NFA Museveni last week okayed the stop planting mark stones along takeover of Busoga University to the boundaries of Olwal Forest relieve the public of last year’s tension as a result of its closure to plant the mark stones last week by the National Council for Higher because the leaders and residents Education (NCHE). protested the re-opening of the “It is over; the people of Busoga boundaries of the forest reserve, and beyond have every reason to claiming that NFA wants to grab smile,” Kadaga said. She said amidst the troubles of the bullets in the air to stop youth from university, a blessing has come after reloading the mark stones onto the President Museveni gave a directive NFA vehicle that had brought them. that the government takes over full control of the university, which is on the brink of collapse. -

Of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya Kevin Brennan

A History of the Absence (and Emergent Presence) of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya Kevin Brennan A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: George Noblit Julius Nyang‟oro James Trier Richard Rodman Gerald Unks © 2008 Kevin Brennan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Kevin Brennan A History of the Absence (and Emergent Presence) of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya (Under the direction of George Noblit and Julius Nyang‟oro) While there is a great deal of literature available about schooling in Kenya and a good deal of writing about the establishment of Kenya‟s public university system there is a significant gap in the literature when it comes to describing and analyzing why certain areas of the country had long been removed from any on-site development of independent university opportunities. This study is an attempt to offer a history of an educational institution – an independent public university at the coast in Kenya – that does not yet exist. This longstanding absence took several significant steps toward transforming to a presence in 2007, when several university colleges were created at the coast. This transformation from absence to presence is a central theme in this work. The research for this project, broadly defined, took place over a seventeen year period and is rooted in both the author‟s professional experience as an educator working in Kenya in the early 1990s as well as his academic interests in comparative and international higher education. -

Kyambogo University Fact Book

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY FACT BOOK Table of Contents Table of Figures: ............................................................................................................................................ 3 List of Tables: ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Preamble: ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgement ....................................................................................................................................... 8 1.0: GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY: ................................................. 10 1.1: Vision: To be a Centre of Academic and Professional Excellence: ............................................... 10 1.2: Mission: ...................................................................................................................................... 10 1.3: Kyambogo Motto: ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.4: Core values: ................................................................................................................................ 10 1.5: Kyambogo University Administrative -

Court Case Administration System

Court Case Administration System http://judccas/ccas/causelistmaker3.php?todate=30-11-2018&fromdat... THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA(HCT) AT KAMPALA LAND REGISTRY CAUSELIST FOR THE SITTINGS OF : 26-11-2018 to 30-11-2018 MONDAY, 26- NOV-2018 HON. MR JUSTICE BEFORE:: COURT ROOM :: KEITIRIMA JOHN EUDES Case Sing Time Case number Pares Claim Posion Category Type DAVID NOAH KALANZI & Hearing HCT-00-LD- Miscellaneous PENDING 1. 09:00 ANOR VS WILSON TAMALE ORDER FRO RE-INSTATEMENT applicant's MA-1075-2018 Applicaon HEARING & ANOR case MUSISI DANIEL SSALONGO Hearing HCT-00-LD- Miscellaneous PENDING 2. 09:00 VS MUGERWA JOSEPH & 2 CONSENT JUDGEMENT BE SET ASIDE applicant's MA-1037-2018 Applicaon HEARING OTHERS case FARIDAH NALULE VS Hearing HCT-00-LD- Miscellaneous PENDING 3. 10:00 COMMISSIONER FOR LAND DISMISSAL ORDER BE SET ASIDE applicant's MA-1091-2018 Applicaon HEARING REGISTRATION & ANOR case Hearing HCT-00-LD- Miscellaneous MARTIN YIGA & ANOR VS RESPONDENT SHOW CAUSE WHY PENDING 4. 11:00 applicant's MC-0088-2018 Cause MULINDWA HENRY CAVEAT LODGED SHOULD NOT LAPSE HEARING case KAMPALA UNIVERSITY Hearing - HCT-00-LD- Miscellaneous PROCEEDINGS IN HCCS NO. 112 OF PENDING 5. 11:30 LIMITED VS LUWERO Applicant's MA-0933-2018 Applicaon 2018 BE STAYED HEARING UNIVERSITY LIMITED case Hearing - HCT-00-LD- Originang DFCU LIMITED VS UGANDA PENDING 6. 11:30 ORDER Plainff's OS-0002-2016 Summons SIGNS LTD & OTHERS HEARING case JOHN STANELY LWANGA VS Hearing - HCT-00-LD- A DECLARATION, GENERAL PENDING 7. 02:00 Civil Suits M.M INVESTMENTS LTD & Plainff's CS-0555-2014 DAMAGES, INTERESTS COSTS HEARING ANOR case WASSWA PETER Hearing HCT-00-LD- Miscellaneous SSERUNKUMA & 3 OTHERS PENDING 8. -

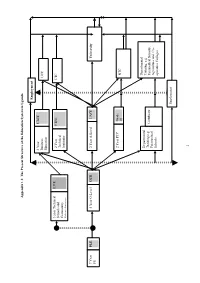

Appendix 1.1: the Present Structure of the Education System in Uganda

Appendix 1.1: The Present Structure of the Education System in Uganda Employment 3 Year UBEE Business UCC Education 3 year Technical UJTE 2 Year UTEE UTC Schools and Technical Community Institutes Polytechniques 7 Year PLE 4 Year O-Level UCE 2 Year A-Level UACE University PS 2 Year PTC Grade III NTC Departmental Departmental Training, e.g Training e.g. Certificate Paramedical Schools, Paramedical Agriculture and Co- Schools operative Colleges Employment I Appendix 1.2a: List of some of the Institutions of Higher Learning in Uganda (Universities (Public and Private) and Public other Tertiary Institutions as per May, 2005) b) Uganda Technical College (UTC)2 1. Universities • UTC Kichwamba • UTC Elgon a) Public • UTC Lira • Makerere University • UTC Masaka • Mbarara University of Science and • UTC Bushenyi Technology • Kyambogo University c) National Teachers’ Colleges (NTC) • Gulu University • NTC Unyama • NTC Kabale b) Public Degree Awarding Other Tertiary • NTC Nagongera Institution • NTC Muni • Uganda Management Institute1 • NTC Kaliro • NTC Mubende c) Private: Chartered Universities • Islamic University in Uganda d) Departmental Training Institutions • Uganda Christian University, Mukono • Uganda Martyrs University (Nkozi) i) Paramedical Schools • Arua Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery d) Private: Licensed to Operate • Butabika Psychiatric Clinical Officers • Bugema University • Butabika School of Nursing • Nkumba University • Fort Portal Clinical Officers School • Kampala International University • Gulu Clinical Officers School • Kampala University • Jinja Nurses and Midwifery • Ndejje University • Kabale Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery • Busoga University • Lira Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery • Kumi University • Masaka School of Comprehensive • Aga Khan University Nursing • Kabale University • Mbale Clinical Officers School • Mountains of the Moon University • Mbale School of Hygiene • Uganda Pentecostal University • Medical Laboratory School, Mulago • African Bible College • Medical Laboratory School, Jinja • Mulago Health Tutors College 2. -

List of Abbreviations

HRNJ - Uganda Human Rights Network for Journalists-Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda) Press Freedom Index Report April 2011 2 HRNJ - Uganda Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Background .............................................................................................. 7 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 7 Elections and Media .............................................................................................. 7 Research Objective ............................................................................................... 8 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 8 Quality check ......................................................................................................... 8 Limitations ............................................................................................................. 9 Part II: Media freedom during national elections in Uganda ................................ 11 Media as a campaign tool ................................................................................... 11 Role of regulatory bodies ................................................................................... 12 Media self censorship ......................................................................................... 14 Censorship of social media -

Kampala City Roads Rehabilitation Project Country: Uganda

Language: English Original: English PROJECT: KAMPALA CITY ROADS REHABILITATION PROJECT COUNTRY: UGANDA ESIA SUMMARY FOR THE PROPOSED SELECTED ROAD LINKS AND JUNCTIONS/INTERSECTIONS TO IMPROVE MOBILITY IN KAMPALA CITY Date: May 2019 Team Leader: G. MAKAJUMA, Transport Engineer, RDGE.3 Preparation Team E&S Team Member: E.B. KAHUBIRE, Social Development Officer, RDGE4 /SNSC 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Traffic congestion in Kampala city is fast growing due to a combination of poor roads network, uncontrolled junctions, and insufficient roads capacity which is out of phase with the increasing traffic (vehicular and pedestrian) on Kampala roads. This congestion results into higher vehicle operating costs, long travel times and poor transport services. The overall city aesthetics and quality of life is highly compromised by the dilapidated paved roads and sidewalks, unpaved shoulders and unpaved roads which are sources of mud and dust that hovers over large sections of the City. 1.2. The Government of Uganda through Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) with support from the African Development Bank intends to improve mobility in Kampala City through improvement of selected road links and Junctions/intersections. The selected junctions/intersections are to be signalized while the selected roads are to be dualled or reconstructed or upgraded to paved standard. 1.3. The National Environmental Act, CAP 153 requires that an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is undertaken for all projects that are listed under the third schedule of the Act with a view of sustainable development. The proposed project is one of the projects listed under Section 3 (Transportation) of the Schedule. Therefore, to fulfill legal requirements an EIA has been conducted for the proposed project as part of the consultancy services for the preliminary and detailed engineering design of selected road links and junctions/intersections to improve mobility in Kampala City under the Second Kampala Institutional and Infrastructure Development Project. -

Designation of Tax Withholding Agents) Notice, 2018

LEGAL NOTICES SUPPLEMENT No. 7 29th June, 2018. LEGAL NOTICES SUPPLEMENT to The Uganda Gazette No. 33, Volume CXI, dated 29th June, 2018. Printed by UPPC, Entebbe, by Order of the Government. Legal Notice No.12 of 2018. THE VALUE ADDED TAX ACT, CAP. 349. The Value Added Tax (Designation of Tax Withholding Agents) Notice, 2018. (Under section 5(2) of the Value Added Tax Act, Cap. 349) IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred upon the Minister responsible for finance by section 5(2) of the Value Added Tax Act, this Notice is issued this 29th day of June, 2018. 1. Title. This Notice may be cited as the Value Added Tax (Designation of Tax Withholding Agents) Notice, 2018. 2. Commencement. This Notice shall come into force on the 1st day of July, 2018. 3. Designation of persons as tax withholding agents. The persons specified in the Schedule to this Notice are designated as value added tax withholding agents for purposes of section 5(2) of the Value Added Tax Act. 1 SCHEDULE LIST OF DESIGNATED TAX WITHOLDING AGENTS Paragraph 3 DS/N TIN TAXPAYER NAME 1 1002736889 A CHANCE FOR CHILDREN 2 1001837868 A GLOBAL HEALTH CARE PUBLIC FOUNDATION 3 1000025632 A.K. OILS AND FATS (U) LIMITED 4 1000024648 A.K. PLASTICS (U) LTD. 5 1000029802 AAR HEALTH SERVICES (U) LIMITED 6 1000025839 ABACUS PARENTERAL DRUGS LIMITED 7 1000024265 ABC CAPITAL BANK LIMITED 8 1008665988 ABIA MEMORIAL TECHNICAL INSTITUTE 9 1002804430 ABIM HOSPITAL 10 1000059344 ABUBAKER TECHNICAL SERVICES AND GENERAL SUPP 11 1000527788 ACTION AFRICA HELP UGANDA 12 1000042267 ACTION AID INTERNATIONAL -

Kampala University Gets Law School

The New Vision Online : Kampala University gets law school Kampala University gets law school Publication date: Tuesday, 8th March, 2011 By Conan Busingye KAMPALA University will start admitting law students in August, the vice-chancellor, Prof. Badru Kateregga, has said. He said the school would admit 80 students for the start. “We submitted our curriculum to the National Council for Higher Education and we are yet to send it to the law council,” Kateregga said. He said the university had stocked the required law literature and was purchasing more. To study law, a candidate must have sat for the Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education and obtained at least two principal passes. All students are legible for admission to the course irrespective of the subjects they offered at A’ level. The previous practice of restricting admission to students who had studied Literature in English, History and Economics was abandoned following a report on legal education training and accreditation in Uganda 1995. Meanwhile, the university will on March 10, hold its eighth graduation ceremony in which 1,266 students will be awarded degrees, diplomas and certificates in various disciplines. Of these, 651 are male and the rest are female. The function, to be presided over by the Chief Justice, Benjamin Odoki, will take place at the university’s main campus in Ggaba. Kampala University has also opened up East African University in Kenya with its programmes accredited by the Kenya Commission for Higher Education. The university has also opened a primary teachers training college in Masaka called Kampala University Primary Teachers College. -

Makerere University As a Flagship Institution: Sustaining the Quest for Relevance

CHAPTER 11 Makerere University as a Flagship Institution: Sustaining the Quest for Relevance Ronald Bisaso INTRODUCTION Makerere University is an interesting case of a traditional university in sub- Saharan Africa. Such universities were established as both national and regional symbols with the main objective of human resource capacity development. Makerere University transformed from a colonial university to a nationalist university, and is, at present, a neoliberal university (Eisemon, 1994; Mamdani, 2008; Musisi, 2003; Obong, 2004). At each stage of transformation of Makerere University as a flagship institution, emphasis on capacity building for human resources, research productivity to contribute to socioeconomic development, and policy development has been evident. This chapter explores those dimensions, as well as such internal processes and dynamics as student enrolment, financing, leader- ship and governance, and the state of the university’s infrastructure. Overall, this chapter studies the contribution of Makerere University to R. Bisaso (*) East African School of Higher Education Studies and Development, College of Education and External Studies, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] © The Author(s) 2017 425 D. Teferra (ed.), Flagship Universities in Africa, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-49403-6_11 426 R. BISASO the knowledge economy through undergraduate and graduate training, research, and policy formulation. The major sources were a review of literature on the university as it relates to the phenomena studied; analysis and interpretation of docu- ments (including reports, strategic plans, and university fact books); dis- cussions with the academic and administrative staff; and finally, seminars to present and discuss the findings with the goal of enhancing the study’s validity and reliability. -

Nkumba Business Journal

Nkumba Business Journal Volume 17, 2018 NKUMBA UNIVERSITY 2018 1 Editor Professor Wilson Muyinda Mande 27 Entebbe Highway Nkumba University P. O. Box 237 Entebbe, Uganda E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] ISSN 1564-068X Published by Nkumba University © 2018 Nkumba University. All rights reserved. No article in this issue may be reprinted, in whole or in part, without written permission from the publisher. Editorial / Advisory Committee Prof. Wilson M. Mande, Nkumba University Assoc. Prof. Michael Mawa, Uganda Martyrs University Dr. Robyn Spencer, Leman College, New York University Prof. E. Vogel, University of Delaware, USA Prof. Nakanyike Musisi, University of Toronto, Canada Dr Jamil Serwanga, Islamic University in Uganda Dr Fred Luzze, Uganda-Case Western Research Collaboration Dr Solomon Assimwe, Nkumba University Dr John Paul Kasujja, Nkumba University Prof. Faustino Orach-Meza, Nkumba University Peer Review Statement All the manuscripts published in Nkumba Business Journal have been subjected to careful screening by the Editor, subjected to blind review and revised before acceptance. Disclaimer Nkumba University and the editorial committee of Nkumba Business Journal make every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in the Journal. However, the University makes no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the suitability for any purpose of the content and disclaim all such representations and warranties whether express or implied to the maximum extent permitted by law. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and are not necessarily the views of the Editor, Nkumba University or their partners. Correspondence Subscriptions, orders, change of address and other matters should be sent to the editor at the above address.