LUNAR SECTION CIRCULAR Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

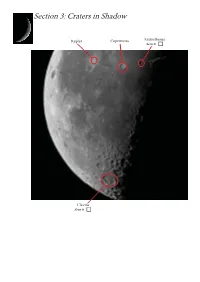

Craters in Shadow

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Feature of the Month – January 2016 Galilaei

A PUBLICATION OF THE LUNAR SECTION OF THE A.L.P.O. EDITED BY: Wayne Bailey [email protected] 17 Autumn Lane, Sewell, NJ 08080 RECENT BACK ISSUES: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html FEATURE OF THE MONTH – JANUARY 2016 GALILAEI Sketch and text by Robert H. Hays, Jr. - Worth, Illinois, USA October 26, 2015 03:32-03:58 UT, 15 cm refl, 170x, seeing 8-9/10 I sketched this crater and vicinity on the evening of Oct. 25/26, 2015 after the moon hid ZC 109. This was about 32 hours before full. Galilaei is a modest but very crisp crater in far western Oceanus Procellarum. It appears very symmetrical, but there is a faint strip of shadow protruding from its southern end. Galilaei A is the very similar but smaller crater north of Galilaei. The bright spot to the south is labeled Galilaei D on the Lunar Quadrant map. A tiny bit of shadow was glimpsed in this spot indicating a craterlet. Two more moderately bright spots are east of Galilaei. The western one of this pair showed a bit of shadow, much like Galilaei D, but the other one did not. Galilaei B is the shadow-filled crater to the west. This shadowing gave this crater a ring shape. This ring was thicker on its west side. Galilaei H is the small pit just west of B. A wide, low ridge extends to the southwest from Galilaei B, and a crisper peak is south of H. Galilaei B must be more recent than its attendant ridge since the crater's exterior shadow falls upon the ridge. -

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

Pete Aldridge Well, Good Afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen, and Welcome to the Fifth and Final Public Hearing of the President’S Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond

The President’s Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy PUBLIC HEARING Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY Monday, May 3, and Tuesday, May 4, 2004 Pete Aldridge Well, good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the fifth and final public hearing of the President’s Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond. I think I can speak for everyone here when I say that the time period since this Commission was appointed and asked to produce a report has elapsed at the speed of light. At least it seems that way. Since February, we’ve heard testimonies from a broad range of space experts, the Mars rovers have won an expanded audience of space enthusiasts, and a renewed interest in space science has surfaced, calling for a new generation of space educators. In less than a month, we will present our findings to the White House. The Commission is here to explore ways to achieve the President’s vision of going back to the Moon and on to Mars and beyond. We have listened and talked to experts at four previous hearings—in Washington, D.C.; Dayton, Ohio; Atlanta, Georgia; and San Francisco, California—and talked among ourselves and we realize that this vision produces a focus not just for NASA but a focus that can revitalize US space capability and have a significant impact on our nation’s industrial base, and academia, and the quality of life for all Americans. As you can see from our agenda, we’re talking with those experts from many, many disciplines, including those outside the traditional aerospace arena. -

Planetary Science : a Lunar Perspective

APPENDICES APPENDIX I Reference Abbreviations AJS: American Journal of Science Ancient Sun: The Ancient Sun: Fossil Record in the Earth, Moon and Meteorites (Eds. R. 0.Pepin, et al.), Pergamon Press (1980) Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 13 Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal Apollo 15: The Apollo 1.5 Lunar Samples, Lunar Science Insti- tute, Houston, Texas (1972) Apollo 16 Workshop: Workshop on Apollo 16, LPI Technical Report 81- 01, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston (1981) Basaltic Volcanism: Basaltic Volcanism on the Terrestrial Planets, Per- gamon Press (1981) Bull. GSA: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America EOS: EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union EPSL: Earth and Planetary Science Letters GCA: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta GRL: Geophysical Research Letters Impact Cratering: Impact and Explosion Cratering (Eds. D. J. Roddy, et al.), 1301 pp., Pergamon Press (1977) JGR: Journal of Geophysical Research LS 111: Lunar Science III (Lunar Science Institute) see extended abstract of Lunar Science Conferences Appendix I1 LS IV: Lunar Science IV (Lunar Science Institute) LS V: Lunar Science V (Lunar Science Institute) LS VI: Lunar Science VI (Lunar Science Institute) LS VII: Lunar Science VII (Lunar Science Institute) LS VIII: Lunar Science VIII (Lunar Science Institute LPS IX: Lunar and Planetary Science IX (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute LPS X: Lunar and Planetary Science X (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XI: Lunar and Planetary Science XI (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XII: Lunar and Planetary Science XII (Lunar and Planetary Institute) 444 Appendix I Lunar Highlands Crust: Proceedings of the Conference in the Lunar High- lands Crust, 505 pp., Pergamon Press (1980) Geo- chim. -

October 2006

OCTOBER 2 0 0 6 �������������� http://www.universetoday.com �������������� TAMMY PLOTNER WITH JEFF BARBOUR 283 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 1 In 1897, the world’s largest refractor (40”) debuted at the University of Chica- go’s Yerkes Observatory. Also today in 1958, NASA was established by an act of Congress. More? In 1962, the 300-foot radio telescope of the National Ra- dio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) went live at Green Bank, West Virginia. It held place as the world’s second largest radio scope until it collapsed in 1988. Tonight let’s visit with an old lunar favorite. Easily seen in binoculars, the hexagonal walled plain of Albategnius ap- pears near the terminator about one-third the way north of the south limb. Look north of Albategnius for even larger and more ancient Hipparchus giving an almost “figure 8” view in binoculars. Between Hipparchus and Albategnius to the east are mid-sized craters Halley and Hind. Note the curious ALBATEGNIUS AND HIPPARCHUS ON THE relationship between impact crater Klein on Albategnius’ southwestern wall and TERMINATOR CREDIT: ROGER WARNER that of crater Horrocks on the northeastern wall of Hipparchus. Now let’s power up and “crater hop”... Just northwest of Hipparchus’ wall are the beginnings of the Sinus Medii area. Look for the deep imprint of Seeliger - named for a Dutch astronomer. Due north of Hipparchus is Rhaeticus, and here’s where things really get interesting. If the terminator has progressed far enough, you might spot tiny Blagg and Bruce to its west, the rough location of the Surveyor 4 and Surveyor 6 landing area. -

July 2020 in This Issue Online Readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 Click on Images an Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for Hyperlinks

A publication of the Lunar Section of ALPO Edited by David Teske: [email protected] 2162 Enon Road, Louisville, Mississippi, USA Recent back issues: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html July 2020 In This Issue Online readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 click on images An Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for hyperlinks. Observations Received 4 By the Numbers 7 Submission Through the ALPO Image Achieve 4 When Submitting Observations to the ALPO Lunar Section 9 Call For Observations Focus-On 9 Focus-On Announcement 10 2020 ALPO The Walter H. Haas Observer’s Award 11 Sirsalis T, R. Hays, Jr. 12 Long Crack, R. Hill 13 Musings on Theophilus, H. Eskildsen 14 Almost Full, R. Hill 16 Northern Moon, H. Eskildsen 17 Northwest Moon and Horrebow, H. Eskildsen 18 A Bit of Thebit, R. Hill 19 Euclides D in the Landscape of the Mare Cognitum (and Two Kipukas?), A. Anunziato 20 On the South Shore, R. Hill 22 Focus On: The Lunar 100, Features 11-20, J. Hubbell 23 Recent Topographic Studies 43 Lunar Geologic Change Detection Program T. Cook 120 Key to Images in this Issue 134 These are the modern Golden Days of lunar studies in a way, with so many new resources available to lu- nar observers. Recently, we have mentioned Robert Garfinkle’s opus Luna Cognita and the new lunar map by the USGS. This month brings us the updated, 7th edition of the Virtual Moon Atlas. These are all wonderful resources for your lunar studies. -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei