Canine Leishmaniasis in Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xhdy-Tdt San Cristobal De Las Casas

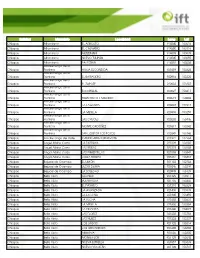

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long Lat Chiapas Acala 2 POTRANCAS 925549 163422 Chiapas Acala 20 DE NOVIEMBRE 925349 163218 Chiapas Acala 6 DE MAYO 925311 163024 Chiapas Acala ACALA 924820 163322 Chiapas Acala ADOLFO LÓPEZ MATEOS 925337 163639 Chiapas Acala AGUA DULCE (BUENOS AIRES) 925100 163001 Chiapas Acala ARTURO MORENO 925345 163349 Chiapas Acala BELÉN 924719 163340 Chiapas Acala BELÉN DOS 925318 162604 Chiapas Acala CAMINO PINTADO 925335 163637 Chiapas Acala CAMPO REAL 925534 163417 Chiapas Acala CARLOS SALINAS DE GORTARI 924957 162538 Chiapas Acala CENTRAL CAMPESINA CARDENISTA 925052 162506 Chiapas Acala CRUZ CHIQUITA 925644 163507 Chiapas Acala CUPIJAMO 924723 163256 Chiapas Acala DOLORES ALFARO 925404 163356 Chiapas Acala DOLORES BUENAVISTA 925512 163408 Chiapas Acala EL AMATAL 924610 162720 Chiapas Acala EL AZUFRE 924555 162629 Chiapas Acala EL BAJÍO 924517 162542 Chiapas Acala EL CALERO 924549 163039 Chiapas Acala EL CANUTILLO 925138 162930 Chiapas Acala EL CENTENARIO 924721 163327 Chiapas Acala EL CERRITO 925100 162910 Chiapas Acala EL CHILAR 924742 163515 Chiapas Acala EL CRUCERO 925152 163002 Chiapas Acala EL FAVORITO 924945 163145 Chiapas Acala EL GIRASOL 925130 162953 Chiapas Acala EL HERRADERO 925446 163354 Chiapas Acala EL PAQUESCH 924933 163324 Chiapas Acala EL PARAÍSO 924740 162810 Chiapas Acala EL PARAÍSO 925610 163441 Chiapas Acala EL PORVENIR 924507 162529 Chiapas Acala EL PORVENIR 925115 162453 Chiapas Acala EL PORVENIR UNO 925307 162530 Chiapas Acala EL RECREO 925119 163429 Chiapas Acala EL RECUERDO 925342 163018 -

Desarrollo Sustentable, Se Ejercieron 198.6 Millones De Pesos

PRESUPUESTO DEVENGADO ENERO - DICIEMBRE 2010 198.6 Millones de Pesos Administración del Agua 35.4 17.8% Protección y Ecosistema Conservación 24.3 del Medio 12.3% Ambiente y los Rececursos Naturales Medio Ambiente 124.0 14.9 62.4% 7.5% Fuente: Organismos Públicos del Gobierno del Estado En el Desarrollo Sustentable, se ejercieron 198.6 millones de pesos. Con el fin de fomentar el desarrollo de la cultura ambiental en comunidades indígenas, se realizaron 4 talleres de capacitación en los principios básicos del cultivo biointensivo de hortalizas. Para el fortalecimiento y conservación de las áreas naturales protegidas de carácter estatal, se elaboraron los documentos cartográficos y programas de manejo de las ANP Humedales La Libertad, del municipio Desarrollo de La Libertad y Humedales de Montaña María Eugenia, del municipio de San Cristóbal de las Casas. Sustentable SUBFUNCIÓN: ADMINISTRACIÓN DEL AGUA ENTIDAD: INSTITUTO ESTATAL DEL AGUA PRINCIPALES ACCIONES Y RESULTADOS Proyecto: Programa Agua Limpia 2010. Con la finalidad de abatir enfermedades de origen hídrico, se realizaron 83 instalaciones de equipos de desinfección en los municipios de Amatán, Chalchihuitán, Chamula, Huitiupán, Mitontic, Oxchuc y San Cristóbal de las Casas, entre otros; asimismo, se repusieron 31 equipos de desinfección en los municipios de Cintalapa, Frontera Comalapa, La Concordia, Pichucalco y Reforma, entre otros; además se instalaron 627 equipos rústicos de desinfección en los municipios de Chanal, Huixtán, Oxchuc y San Juan Cancúc; así también, se realizaron 2,218 monitoreos de cloro residual, además se llevo a cabo el suministro de 410 toneladas de hipoclorito de calcio y 209 piezas de ión plata, en diversos municipios del Estado; de igual manera se efectuaron 10 operativo de saneamiento en los municipios de Yajalón, Suchiapa, Soyaló, entre otros. -

Af092e00.Pdf

Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico - UNAM Wood Energy Programme – FAO Forestry Department FUELWOOD “HOT SPOTS” IN MEXICO: A CASE STUDY USING WISDOM – Woodfuel Integrated Supply-Demand Overview Mapping Omar R. Masera, Gabriela Guerrero, Adrián Ghilardi Centro de Investigationes en Ecosistemas CIECO - UNAM Alejandro Velázquez, Jean F. Mas Instituto de Geografía- UNAM María de Jesús Ordóñez CRIM- UNAM Rudi Drigo Wood Energy Planning and Policy Development - FAO-EC Partnership Programme and Miguel A. Trossero Wood Energy Programme, Forest Products and Economics Division - FAO FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2004 5IFEFTJHOBUJPOTFNQMPZFEBOEUIFQSFTFOUBUJPOPGNBUFSJBM JOUIJTJOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUEPOPUJNQMZUIFFYQSFTTJPOPGBOZ PQJOJPOXIBUTPFWFSPOUIFQBSUPGUIF'PPEBOE"HSJDVMUVSF 0SHBOJ[BUJPO PG UIF 6OJUFE /BUJPOT DPODFSOJOH UIF MFHBM PS EFWFMPQNFOUTUBUVTPGBOZDPVOUSZ UFSSJUPSZ DJUZPSBSFBPSPG JUTBVUIPSJUJFT PSDPODFSOJOHUIFEFMJNJUBUJPOPGJUTGSPOUJFST PSCPVOEBSJFT "MM SJHIUT SFTFSWFE 3FQSPEVDUJPO BOE EJTTFNJOBUJPO PG NBUFSJBM JO UIJT JOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUGPSFEVDBUJPOBMPSPUIFSOPODPNNFSDJBMQVSQPTFTBSF BVUIPSJ[FEXJUIPVUBOZQSJPSXSJUUFOQFSNJTTJPOGSPNUIFDPQZSJHIUIPMEFST QSPWJEFEUIFTPVSDFJTGVMMZBDLOPXMFEHFE3FQSPEVDUJPOPGNBUFSJBMJOUIJT JOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUGPSSFTBMFPSPUIFSDPNNFSDJBMQVSQPTFTJTQSPIJCJUFE XJUIPVUXSJUUFOQFSNJTTJPOPGUIFDPQZSJHIUIPMEFST"QQMJDBUJPOTGPSTVDI QFSNJTTJPOTIPVMECFBEESFTTFEUPUIF$IJFG 1VCMJTIJOH.BOBHFNFOU4FSWJDF *OGPSNBUJPO%JWJTJPO '"0 7JBMFEFMMF5FSNFEJ$BSBDBMMB 3PNF *UBMZ PSCZFNBJMUPDPQZSJHIU!GBPPSH ª '"0 Fuelwood “hot -

(2000-2007). Socio-Spatial Differentiation of the Ejection Contexts

https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v25i78.4739 International Migrations from Chiapas (2000-2007). Socio-spatial Differentiation of the Ejection Contexts Guillermo Castillo / [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8188-9929 Jorge González / [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2199-8389 María José Ibarrola / [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4501-0408 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México Abstract: Regarding migration changes between Mexico and the USA, this study focuses on the increase and diversification of migration between Chiapas and the USA during the period 2000-2007. This paper argues that not only economic conditions are the explanation to these migrations but also, in certain regions, political processes and impacts of natural disasters were important drivers for migration –a combination of causes in the context of migration–. Based on different sources (indicators of migration intensity, index on the remittance reception, migratory censuses, demographic surveys, quantitative and qualitative migratory studies), the increase in migration is shown at a state and regional level. Furthermore, the increase of migration in certain regions is assessed in relation with its causes (social, environmental, political and economic) showing that, migrations are multi- causal processes spatially differentiated on the basis of the migrants’ place of origin. Key words: international migration, Chiapas, migration contexts, migrants, development. Resumen: En el marco de las transformaciones de la migración México-Estados Unidos (EU) en el cambio de siglo, este artículo tiene como objetivo abordar el crecimiento y diversificación de las migraciones chiapanecas a EU (2000-2007). El aporte del trabajo es mostrar que si bien las condiciones económicas son relevantes para explicar las migraciones, también en ciertas regiones chiapanecas hubo procesos políticos y de impactos de desastres naturales para el surgimiento de estas migraciones –una articulación de causas en los contextos de expulsión–. -

XXIII.- Estadística De Población

Estadística de Población Capítulo XXIII Estadística de Población La estadística de población tiene como finalidad apoyar a los líderes de proyectos en la cuantificación de la programación de los beneficiarios de los proyectos institucionales e inversión. Con base a lo anterior, las unidades responsables de los organismos públicos contaran con elementos que faciliten la toma de decisiones en el registro de los beneficiarios, clasificando a la población total a nivel regional y municipal en las desagregaciones siguientes: Género Hombre- Mujer Ubicación por Zona Urbana – Rural Origen Poblacional Mestiza, Indígena, Inmigrante Grado Marginal Muy alto, Alto, Medio, Bajo y Muy Bajo La información poblacional para 2014 se determinó con base a lo siguiente: • Los datos de población por municipio, se integraron con base a las proyecciones 2010 – 2030, publicados por el Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO): población a mitad de año por sexo y edad, y población de los municipios a mitad de año por sexo y grupos de edad. • El grado marginal, es tomada del índice y grado de marginación, lugar que ocupa Chiapas en el contexto nacional y estatal por municipio, emitidos por el CONAPO. • Los datos de la población indígena, fueron determinados acorde al porcentaje de población de 3 años y más que habla lengua indígena; emitidos por el Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), en el Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010; multiplicada por la población proyectada. • Los datos de la clasificación de población urbana y rural, se determinaron con base al Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010, emitido por el INEGI; considerando como población rural a las personas que habitan en localidades con menos de 2,500 habitantes. -

Xhcom-Tdt Comitan De Dominguez

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long Lat Chiapas Altamirano EL ARBOLITO 914540 163018 Chiapas Altamirano EL CALVARIO 914350 163116 Chiapas Altamirano GETZEMANÍ 914609 163039 Chiapas Altamirano NUEVO TULIPÁN 914545 163055 Chiapas Altamirano PALESTINA 914552 163035 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera AGUA ESCONDIDA 921059 153324 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera EL BAÑADERO 920916 153220 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera EL ZAPOTE 920903 153207 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera ESCOBILLAL 920827 153211 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera FRANCISCO I. MADERO 920519 153050 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera LA LAGUNITA 920607 152913 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera LA MESILLA 920938 153255 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera LAS CRUCES 920208 153445 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera MONTE ORDÓÑEZ 921017 153342 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera SAN JOSÉ DE LOS POZOS 920342 153146 Chiapas Amatenango del Valle CANDELARIA BUENAVISTA 921921 162904 Chiapas Angel Albino Corzo LA TARRAYA 923128 154105 Chiapas Angel Albino Corzo LAS BRISAS 923123 154105 Chiapas Angel Albino Corzo LAS PIMIENTILLAS 923355 153847 Chiapas Angel Albino Corzo LOMA BONITA 923351 153831 Chiapas Bejucal de Ocampo EL LIMÓN 921153 152754 Chiapas Bejucal de Ocampo JUSTO SIERRA 921045 153244 Chiapas Bejucal de Ocampo LA SOLEDAD 920949 153129 Chiapas Bella Vista ALLENDE 921325 153917 Chiapas Bella Vista BUENAVISTA 921735 153443 Chiapas Bella Vista EL PARAÍSO 921215 153329 Chiapas Bella Vista LA AVANZADA 921430 153939 Chiapas Bella Vista LA LAGUNA 921845 153455 Chiapas Bella Vista LA LUCHA -

CHIAPAS* Municipios Entidad Tipo De Ente Público Nombre Del Ente Público

Inventario de Entes Públicos CHIAPAS* Municipios Entidad Tipo de Ente Público Nombre del Ente Público Chiapas Municipio 07-001 Acacoyagua Chiapas Municipio 07-002 Acala Chiapas Municipio 07-003 Acapetahua Chiapas Municipio 07-004 Altamirano Chiapas Municipio 07-005 Amatán Chiapas Municipio 07-006 Amatenango de la Frontera Chiapas Municipio 07-007 Amatenango del Valle Chiapas Municipio 07-008 Ángel Albino Corzo Chiapas Municipio 07-009 Arriaga Chiapas Municipio 07-010 Bejucal de Ocampo Chiapas Municipio 07-011 Bella Vista Chiapas Municipio 07-012 Berriozábal Chiapas Municipio 07-013 Bochil * Inventario elaborado con información del CACEF y EFSL. 19 de marzo de 2020 Inventario de Entes Públicos ChiapasCHIAPAS* Municipio 07-014 El Bosque Chiapas Municipio 07-015 Cacahoatán Chiapas Municipio 07-016 Catazajá Chiapas Municipio 07-017 Cintalapa Chiapas Municipio 07-018 Coapilla Chiapas Municipio 07-019 Comitán de Domínguez Chiapas Municipio 07-020 La Concordia Chiapas Municipio 07-021 Copainalá Chiapas Municipio 07-022 Chalchihuitán Chiapas Municipio 07-023 Chamula Chiapas Municipio 07-024 Chanal Chiapas Municipio 07-025 Chapultenango Chiapas Municipio 07-026 Chenalhó Chiapas Municipio 07-027 Chiapa de Corzo Chiapas Municipio 07-028 Chiapilla Chiapas Municipio 07-029 Chicoasén Inventario de Entes Públicos ChiapasCHIAPAS* Municipio 07-030 Chicomuselo Chiapas Municipio 07-031 Chilón Chiapas Municipio 07-032 Escuintla Chiapas Municipio 07-033 Francisco León Chiapas Municipio 07-034 Frontera Comalapa Chiapas Municipio 07-035 Frontera Hidalgo Chiapas -

Resolutivo De La Comisión Nacional De Elecciones

RESOLUTIVO DE LA COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE ELECCIONES SOBRE EL PROCESO INTERNO LOCAL DEL ESTADO DE CHIAPAS (LISTA APROBADA DE REGISTROS PARA LAS CANDIDATURAS DE SÍNDICOS) México DF., a 22 de mayo de 2015 De conformidad con lo establecido en el Estatuto de Morena y la Convocatoria para la selección de candidaturas para diputadas y diputados al Congreso del estado por el principio de mayoría relativa, así como de presidentes municipales y síndicos para el proceso electoral 2015 en el estado de Chiapas; la Comisión Nacional de Elecciones de Morena da a conocer la relación de solicitudes de registro aprobadas: SÍNDICOS: NUM. MUNICIPIO A. PATERNO A. MATERNO NOMBRE (S) 1 ACACOYAGUA NISHIZAWA RABANALES CESAR 2 ACALA 3 ACAPETAHUA 4 ALDAMA 5 ALTAMIRANO 6 AMATAN AMATENANGO DE LA 7 FRONTERA 8 AMATENANGO DEL VALLE 9 ANGEL ALBINO CORZO 10 ARRIAGA ESCOBAR DIAZ LUZ PATRICIA 11 BEJUCAL DE OCAMPO 12 BELISARIO DOMINGUEZ 13 BELLAVISTA BENEMERITO DE LAS 14 AMERICAS GOMEZ SANTOS CELINA 15 BERRIOZABAL 16 BOCHIL HERNANDEZ DIAZ MARIA DEL ROSARIO 17 CACAHOATAN MORALES RAMIREZ VELIA MATILDE 18 CATAZAJA 19 CHALCHIHUITAN 20 CHAMULA 21 CHANAL 22 CHAPULTENANGO 23 CHENALHO PEREZ GUTIERREZ JUANA 24 CHIAPA DE CORZO PAVÓN PEREZ SARA 25 CHIAPILLA 26 CHICOASEN 27 CHICOMUSELO GARCIA PEREZ HIPOLITA 28 CHILON 29 CINTALAPA CRUZ MORALES JEZIKA 30 COAPILLA SANCHEZ LOPEZ MARIA FLOR 31 COMITAN DE DOMINGUEZ 32 COPAINALA MORALES TOVILLA IRENE LULU 33 EL BOSQUE 34 EL PORVENIR MORALES MEJIA ENRIQUETA MELINA 35 EMILIANO ZAPATA 36 ESCUINTLA 37 FRANCISCO LEON 38 FRONTERA COMALAPA PEREZ CASTILLEJOS -

Chiapas Clave De Entidad Nombre De Entidad Clave De

CHIAPAS CLAVE DE NOMBRE DE CLAVE DE ÁREA NOMBRE DE MUNICIPIO ENTIDAD ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO GEOGRÁFICA 07 Chiapas 001 Acacoyagua C 07 Chiapas 002 Acala C 07 Chiapas 003 Acapetahua C 07 Chiapas 004 Altamirano C 07 Chiapas 005 Amatán C 07 Chiapas 006 Amatenango de la Frontera C 07 Chiapas 007 Amatenango del Valle C 07 Chiapas 008 Angel Albino Corzo C 07 Chiapas 009 Arriaga C 07 Chiapas 010 Bejucal de Ocampo C 07 Chiapas 011 Bella Vista C 07 Chiapas 012 Berriozábal C 07 Chiapas 013 Bochil C 07 Chiapas 014 El Bosque C 07 Chiapas 015 Cacahoatán C 07 Chiapas 016 Catazajá C 07 Chiapas 017 Cintalapa C 07 Chiapas 018 Coapilla C 07 Chiapas 019 Comitán de Domínguez C 07 Chiapas 020 La Concordia C 07 Chiapas 021 Copainalá C 07 Chiapas 022 Chalchihuitán C 07 Chiapas 023 Chamula C 07 Chiapas 024 Chanal C 07 Chiapas 025 Chapultenango C 07 Chiapas 026 Chenalhó C 07 Chiapas 027 Chiapa de Corzo C 07 Chiapas 028 Chiapilla C 07 Chiapas 029 Chicoasén C 07 Chiapas 030 Chicomuselo C 07 Chiapas 031 Chilón C 07 Chiapas 032 Escuintla C 07 Chiapas 033 Francisco León C 07 Chiapas 034 Frontera Comalapa C 07 Chiapas 035 Frontera Hidalgo C 07 Chiapas 036 La Grandeza C 07 Chiapas 037 Huehuetán C 07 Chiapas 038 Huixtán C 07 Chiapas 039 Huitiupán C 07 Chiapas 040 Huixtla C 07 Chiapas 041 La Independencia C CHIAPAS CLAVE DE NOMBRE DE CLAVE DE ÁREA NOMBRE DE MUNICIPIO ENTIDAD ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO GEOGRÁFICA 07 Chiapas 042 Ixhuatán C 07 Chiapas 043 Ixtacomitán C 07 Chiapas 044 Ixtapa C 07 Chiapas 045 Ixtapangajoya C 07 Chiapas 046 Jiquipilas C 07 Chiapas 047 Jitotol C 07 Chiapas -

Catálogo PEX Tapilula Chiapas.Xlsx

Catálogo de las emisoras de radio y televisión que participarán en el Proceso Local Extraordinario en el Municipio de Tapilula en el estado de Chiapas Emisoras que se escuchan y ven en la entidad Cobertura municipal Transmite menos Cuenta autorización Localidad Nombre del concesionario / Frecuencia / Nombre de la Cobertura Cobertura distrital N° Domiciliada Medio Régimen Siglas Tipo de emisora de 18 horas para transmitir en ingles Ubicación permisionario Canal estación distrital federal local (pauta ajustada) o en alguna lengua Amatán, Berriozábal, Bochil, Chamula,Chapultenango,Chiapa de Corzo, Chicoasén, Coapilla, Copainalá, El Bosque, Francisco León, Ixhuatán, Ixtacomitán, Ixtapa, Ixtapangajoya, Jiquipilas, Jitotol, Larráinzar, Ocotepec, Ocozocoautla de Comisión Nacional para el La Voz de los 1,2,3,10,11,12,13,14 1 Chiapas Copainalá Radio Permiso XECOPA-AM 1210 Khz. AM 2,4,5,6,9,10 Espinosa, Ostuacán, Osumacinta, Pantepec, Pichucalco, Sí Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas Vientes ,22 Pueblo Nuevo Solistahuacán, Rayón, San Fernando, Simojovel, Solosuchiapa, Soyaló, Suchiapa, Sunuapa, Tapalapa, Tapilula, Tecpatán, Tuxtla Gutiérrez Acala, Amatán, Amatenango del Valle, Berriozábal, Bochil, Chalchihuitán,Chamula, Chapultenango,Chenalhó, Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapilla,Chicoasén, Cintalapa, Coapilla, Copainalá, El Bosque, Francisco León, Huitiupán, Huixtán, Ixhuatán, Ixtacomitán, Ixtapa, Ixtapangajoya, Jiquipilas, Jitotol, La Concordia, Larráinzar, Mitontic, Nicolás Ruíz, Ocotepec, Ocozocoautla de Espinosa, Ostuacán, Osumacinta, Oxchuc, XETG, La Grande del Sureste, S.A. XETG-AM 990 Khz. La Grande del 1,2,3,4,5,8,10,11,12, Pantelhó, Pantepec, Pichucalco, Pueblo Nuevo Solistahuacán, 2 Chiapas Tuxtla Gutiérrez Radio Concesión Migración AM-FM 1,2,3,4,5,6,9,10 de C.V. XHTG-FM 90.3 Mhz. -

La Alternancia Política Municipal Más Allá Del Cambio De Partidos Políticos

CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DOCENCIA ECONÓMICAS, A.C. LA ALTERNANCIA POLÍTICA MUNICIPAL MÁS ALLÁ DEL CAMBIO DE PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS: EL CASO DE CHIAPAS TESINA QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN CIENCIA POLÍTICA Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES PRESENTA ÁNGEL EDUARDO ALVARADO GÓMEZ DIRECTOR DE LA TESINA: LIC. IGNACIO MARVÁN LABORDE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO SEPTIEMBRE DE 2018 Dedicatoria Agradecimientos Por aquél que, sin ningún llamado ni obligación, siempre está sonriente recordándome que vamos bien y que viene lo mejor sin importar qué. Porque llorar sobre un tractor no es ningún motivo de vergüenza si el llanto viene del más profundo sentido de que perteneces a la cultura del esfuerzo y de que ya no cultivarás más milpa si eso es lo que se requiere para cultivar tus sueños. Por aquella que me hacía bailar cuando era un pichito porque no me dormía si no me bailaba. Por aquella que desempolvó su suave kujchil para arrullar a un par de nenes sin papá, cuando su hija se tuvo que ir a trabajar para traer el pan a la casa, como si 40 años horneando los salvadillos y las cemitas más sabrosas de Zapaluta no fueran suficiente mérito ya. Llevas en tu nombre la Z de Zacarías y también la I de Isabel. Porque eso de ser madre a los sesenta o a los setenta años no sólo ocurre en la Biblia. Por aquél que repintó sus camisas, remendó sus pantalones y hasta sus trusas; sin olvidar que postergó su derecho a procrear muchos años, ya que la vida le había dado unos hijos que ni siquiera sabían pronunciar su nombre de manera correcta, pero que lo veían y lo ven como sólo Dios sabe. -

Informe Local

Capacidad institucional para la adaptación al cambio climático: Medición multidimensional a nivel municipal en México CHIAPAS Informe local Transparencia Mexicana (TM), en coordinación con el Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático (INECC) y el Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo generaron en 2017 la Medición Multidimensional de Capacidad Institucional que Fomente la Capacidad Adaptativa ante el Cambio Climático a nivel Municipal (base de datos MCI 2015). El objetivo de este ejercicio fue analizar el desempeño a nivel municipal en términos de la capacidad institucional que tienen los gobiernos locales para fomentar la adaptación al cambio climático en el corto, mediano y largo plazos. En julio de 2018, nueve entidades federativas tuvieron elecciones para cambio de gobernador y presidentes municipales. Transparencia Mexicana considera relevante y necesario brindar información oportuna sobre los rasgos que existen en los municipios a nivel institucional para la creación de capacidades en torno a la adaptación al cambio climático en México. Este informe estatal sobre la MCI 2015 se divide en tres secciones: (1) antecedentes de la MCI; (2) la perspectiva general del estado, que incluye su desempeño en la MCI, junto Transparencia Mexicana, A. C. con un diagnóstico de la capacidad institucional de los municipios o alcaldías en términos de sus capacidades de Eduardo Bohórquez Director Ejecutivo respuesta y adaptativas ante los efectos del cambio climático; y (3) análisis municipal o de alcaldías, que aborda el análisis de COORDINACIÓN OPERATIVA tres municipios o alcaldías para ilustrar la utilidad de los indicadores de la MCI. En concreto, municipios que son Coordinador técnico capitales estatales o alcaldía de interés y que presentan los Vania Montalvo valores más altos y más bajos de capacidad institucional por Arturo Cortés Coordinadores del proyecto estado.