On Laplace Continued Fraction for the Normal Integral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Hills State University

Black Hills State University MATH 341 Concepts addressed: Mathematics Number sense and numeration: meaning and use of numbers; the standard algorithms of the four basic operations; appropriate computation strategies and reasonableness of results; methods of mathematical investigation; number patterns; place value; equivalence; factors and multiples; ratio, proportion, percent; representations; calculator strategies; and number lines Students will be able to demonstrate proficiency in utilizing the traditional algorithms for the four basic operations and to analyze non-traditional student-generated algorithms to perform these calculations. Students will be able to use non-decimal bases and a variety of numeration systems, such as Mayan, Roman, etc, to perform routine calculations. Students will be able to identify prime and composite numbers, compute the prime factorization of a composite number, determine whether a given number is prime or composite, and classify the counting numbers from 1 to 200 into prime or composite using the Sieve of Eratosthenes. A prime number is a number with exactly two factors. For example, 13 is a prime number because its only factors are 1 and itself. A composite number has more than two factors. For example, the number 6 is composite because its factors are 1,2,3, and 6. To determine if a larger number is prime, try all prime numbers less than the square root of the number. If any of those primes divide the original number, then the number is prime; otherwise, the number is composite. The number 1 is neither prime nor composite. It is not prime because it does not have two factors. It is not composite because, otherwise, it would nullify the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic, which states that every composite number has a unique prime factorization. -

Saxon Course 1 Reteachings Lessons 21-30

Name Reteaching 21 Math Course 1, Lesson 21 • Divisibility Last-Digit Tests Inspect the last digit of the number. A number is divisible by . 2 if the last digit is even. 5 if the last digit is 0 or 5. 10 if the last digit is 0. Sum-of-Digits Tests Add the digits of the number and inspect the total. A number is divisible by . 3 if the sum of the digits is divisible by 3. 9 if the sum of the digits is divisible by 9. Practice: 1. Which of these numbers is divisible by 2? A. 2612 B. 1541 C. 4263 2. Which of these numbers is divisible by 5? A. 1399 B. 1395 C. 1392 3. Which of these numbers is divisible by 3? A. 3456 B. 5678 C. 9124 4. Which of these numbers is divisible by 9? A. 6754 B. 8124 C. 7938 Saxon Math Course 1 © Harcourt Achieve Inc. and Stephen Hake. All rights reserved. 23 Name Reteaching 22 Math Course 1, Lesson 22 • “Equal Groups” Word Problems with Fractions What number is __3 of 12? 4 Example: 1. Divide the total by the denominator (bottom number). 12 ÷ 4 = 3 __1 of 12 is 3. 4 2. Multiply your answer by the numerator (top number). 3 × 3 = 9 So, __3 of 12 is 9. 4 Practice: 1. If __1 of the 18 eggs were cracked, how many were not cracked? 3 2. What number is __2 of 15? 3 3. What number is __3 of 72? 8 4. How much is __5 of two dozen? 6 5. -

Continued Fractions: Introduction and Applications

PROCEEDINGS OF THE ROMAN NUMBER THEORY ASSOCIATION Volume 2, Number 1, March 2017, pages 61-81 Michel Waldschmidt Continued Fractions: Introduction and Applications written by Carlo Sanna The continued fraction expansion of a real number x is a very efficient process for finding the best rational approximations of x. Moreover, continued fractions are a very versatile tool for solving problems related with movements involving two different periods. This situation occurs both in theoretical questions of number theory, complex analysis, dy- namical systems... as well as in more practical questions related with calendars, gears, music... We will see some of these applications. 1 The algorithm of continued fractions Given a real number x, there exist an unique integer bxc, called the integral part of x, and an unique real fxg 2 [0; 1[, called the fractional part of x, such that x = bxc + fxg: If x is not an integer, then fxg , 0 and setting x1 := 1=fxg we have 1 x = bxc + : x1 61 Again, if x1 is not an integer, then fx1g , 0 and setting x2 := 1=fx1g we get 1 x = bxc + : 1 bx1c + x2 This process stops if for some i it occurs fxi g = 0, otherwise it continues forever. Writing a0 := bxc and ai = bxic for i ≥ 1, we obtain the so- called continued fraction expansion of x: 1 x = a + ; 0 1 a + 1 1 a2 + : : a3 + : which from now on we will write with the more succinct notation x = [a0; a1; a2; a3;:::]: The integers a0; a1;::: are called partial quotients of the continued fraction of x, while the rational numbers pk := [a0; a1; a2;:::; ak] qk are called convergents. -

RATIO and PERCENT Grade Level: Fifth Grade Written By: Susan Pope, Bean Elementary, Lubbock, TX Length of Unit: Two/Three Weeks

RATIO AND PERCENT Grade Level: Fifth Grade Written by: Susan Pope, Bean Elementary, Lubbock, TX Length of Unit: Two/Three Weeks I. ABSTRACT A. This unit introduces the relationships in ratios and percentages as found in the Fifth Grade section of the Core Knowledge Sequence. This study will include the relationship between percentages to fractions and decimals. Finally, this study will include finding averages and compiling data into various graphs. II. OVERVIEW A. Concept Objectives for this unit: 1. Students will understand and apply basic and advanced properties of the concept of ratios and percents. 2. Students will understand the general nature and uses of mathematics. B. Content from the Core Knowledge Sequence: 1. Ratio and Percent a. Ratio (p. 123) • determine and express simple ratios, • use ratio to create a simple scale drawing. • Ratio and rate: solve problems on speed as a ratio, using formula S = D/T (or D = R x T). b. Percent (p. 123) • recognize the percent sign (%) and understand percent as “per hundred” • express equivalences between fractions, decimals, and percents, and know common equivalences: 1/10 = 10% ¼ = 25% ½ = 50% ¾ = 75% find the given percent of a number. C. Skill Objectives 1. Mathematics a. Compare two fractional quantities in problem-solving situations using a variety of methods, including common denominators b. Use models to relate decimals to fractions that name tenths, hundredths, and thousandths c. Use fractions to describe the results of an experiment d. Use experimental results to make predictions e. Use table of related number pairs to make predictions f. Graph a given set of data using an appropriate graphical representation such as a picture or line g. -

Period of the Continued Fraction of N

√ Period of the Continued Fraction of n Marius Beceanu February 5, 2003 Abstract This paper seeks to recapitulate the known facts√ about the length of the period of the continued fraction expansion of n as a function of n and to make a few (possibly) original contributions. I have√ established a result concerning the average period length for k < n < k + 1, where k is an integer, and, following numerical experiments, tried to formulate the best possible bounds for this average length and for the √maximum length√ of the period of the continued fraction expansion of n, with b nc = k. Many results used in the course of this paper are borrowed from [1] and [2]. 1 Preliminaries Here are some basic definitions and results that will prove useful throughout the paper. They can also be probably found in any number theory intro- ductory course, but I decided to include them for the sake of completeness. Definition 1.1 The integer part of x, or bxc, is the unique number k ∈ Z with the property that k ≤ x < k + 1. Definition 1.2 The continued fraction expansion of a real number x is the sequence of integers (an)n∈N obtained by the recurrence relation 1 x0 = x, an = bxcn, xn+1 = , for n ∈ N. xn − an Let us also construct the sequences P0 = a0,Q0 = 1, P1 = a0a1 + 1,Q1 = a1, 1 √ 2 Period of the Continued Fraction of n and in general Pn = Pn−1an + Pn−2,Qn = Qn−1an + Qn−2, for n ≥ 2. It is obvious that, since an are positive, Pn and Qn are strictly increasing for n ≥ 1 and both are greater or equal to Fn (the n-th Fibonacci number). -

Random Denominators and the Analysis of Ratio Data

Environmental and Ecological Statistics 11, 55-71, 2004 Corrected version of manuscript, prepared by the authors. Random denominators and the analysis of ratio data MARTIN LIERMANN,1* ASHLEY STEEL, 1 MICHAEL ROSING2 and PETER GUTTORP3 1Watershed Program, NW Fisheries Science Center, 2725 Montlake Blvd. East, Seattle, WA 98112 E-mail: [email protected] 2Greenland Institute of Natural Resources 3National Research Center for Statistics and the Environment, Box 354323, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 Ratio data, observations in which one random value is divided by another random value, present unique analytical challenges. The best statistical technique varies depending on the unit on which the inference is based. We present three environmental case studies where ratios are used to compare two groups, and we provide three parametric models from which to simulate ratio data. The models describe situations in which (1) the numerator variance and mean are proportional to the denominator, (2) the numerator mean is proportional to the denominator but its variance is proportional to a quadratic function of the denominator and (3) the numerator and denominator are independent. We compared standard approaches for drawing inference about differences between two distributions of ratios: t-tests, t-tests with transformations, permutation tests, the Wilcoxon rank test, and ANCOVA-based tests. Comparisons between tests were based both on achieving the specified alpha-level and on statistical power. The tests performed comparably with a few notable exceptions. We developed simple guidelines for choosing a test based on the unit of inference and relationship between the numerator and denominator. Keywords: ANCOVA, catch per-unit effort, fish density, indices, per-capita, per-unit, randomization tests, t-tests, waste composition 1352-8505 © 2004 Kluwer Academic Publishers 1. -

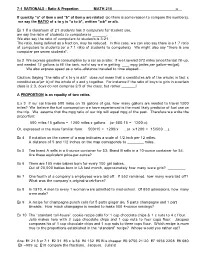

7-1 RATIONALS - Ratio & Proportion MATH 210 F8

7-1 RATIONALS - Ratio & Proportion MATH 210 F8 If quantity "a" of item x and "b" of item y are related (so there is some reason to compare the numbers), we say the RATIO of x to y is "a to b", written "a:b" or a/b. Ex 1 If a classroom of 21 students has 3 computers for student use, we say the ratio of students to computers is . We also say the ratio of computers to students is 3:21. The ratio, being defined as a fraction, may be reduced. In this case, we can also say there is a 1:7 ratio of computers to students (or a 7:1 ratio of students to computers). We might also say "there is one computer per seven students" . Ex 2 We express gasoline consumption by a car as a ratio: If w e traveled 372 miles since the last fill-up, and needed 12 gallons to fill the tank, we'd say we're getting mpg (miles per gallon— mi/gal). We also express speed as a ratio— distance traveled to time elapsed... Caution: Saying “ the ratio of x to y is a:b” does not mean that x constitutes a/b of the whole; in fact x constitutes a/(a+ b) of the whole of x and y together. For instance if the ratio of boys to girls in a certain class is 2:3, boys do not comprise 2/3 of the class, but rather ! A PROPORTION is an equality of tw o ratios. E.x 3 If our car travels 500 miles on 15 gallons of gas, how many gallons are needed to travel 1200 miles? We believe the fuel consumption we have experienced is the most likely predictor of fuel use on the trip. -

Measurement & Transformations

Chapter 3 Measurement & Transformations 3.1 Measurement Scales: Traditional Classifica- tion Statisticians call an attribute on which observations differ a variable. The type of unit on which a variable is measured is called a scale.Traditionally,statisticians talk of four types of measurement scales: (1) nominal,(2)ordinal,(3)interval, and (4) ratio. 3.1.1 Nominal Scales The word nominal is derived from nomen,theLatinwordforname.Nominal scales merely name differences and are used most often for qualitative variables in which observations are classified into discrete groups. The key attribute for anominalscaleisthatthereisnoinherentquantitativedifferenceamongthe categories. Sex, religion, and race are three classic nominal scales used in the behavioral sciences. Taxonomic categories (rodent, primate, canine) are nomi- nal scales in biology. Variables on a nominal scale are often called categorical variables. For the neuroscientist, the best criterion for determining whether a variable is on a nominal scale is the “plotting” criteria. If you plot a bar chart of, say, means for the groups and order the groups in any way possible without making the graph “stupid,” then the variable is nominal or categorical. For example, were the variable strains of mice, then the order of the means is not material. Hence, “strain” is nominal or categorical. On the other hand, if the groups were 0 mgs, 10mgs, and 15 mgs of active drug, then having a bar chart with 15 mgs first, then 0 mgs, and finally 10 mgs is stupid. Here “milligrams of drug” is not anominalorcategoricalvariable. 1 CHAPTER 3. MEASUREMENT & TRANSFORMATIONS 2 3.1.2 Ordinal Scales Ordinal scales rank-order observations. -

POLYNOMIAL CONTINUED FRACTIONS 1. Introduction A

POLYNOMIAL CONTINUED FRACTIONS D. BOWMAN AND J. MC LAUGHLIN Abstract. Continued fractions whose elements are polynomial se- quences have been carefully studied mostly in the cases where the degree of the numerator polynomial is less than or equal to two and the degree of the denominator polynomial is less than or equal to one. Here we study cases of higher degree for both numerator and denominator poly- nomials, with particular attention given to cases in which the degrees are equal. We extend work of Ramanujan on continued fractions with rational limits and also consider cases where the limits are irrational. 1. Introduction 1 A polynomial continued fraction is a continued fraction Kn=1an=bn where an and bn are polynomials in n. Most well known continued fractions are of this type. For example the first continued fractions giving values for ¼ (due to Lord Brouncker, first published in [10]) and e ([3]) are of this type: 4 1 (2n ¡ 1)2 (1.1) = 1 + K ; ¼ n=1 2 1 (1.2) e = 2 + 1 n : 1 + K n=1 n + 1 Here we use the standard notations N an a1 K := n=1 bn a2 b1 + a3 b2 + aN b3 + ::: + bN a a a a = 1 2 3 ::: N : b1+ b2+ b3+ bN We write AN =BN for the above finite continued fraction written as a rational 1 function of the variables a1; :::; aN ; b1; :::; bN . By Kn=1an=bn we mean the limit of the sequence fAn=Bng as n goes to infinity, if the limit exists. The first systematic treatment of this type of continued fraction seems to be in Perron [7] where degrees through two for an and degree one for bn are 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. -

Proportions: a Ratio Is the Quotient of Two Numbers. for Example, 2 3 Is A

Proportions: 2 A ratio is the quotient of two numbers. For example, is a ratio of 2 and 3. 3 An equality of two ratios is a proportion. For example, 3 15 = is a proportion. 7 45 If two sets of numbers (none of which is 0) are in a proportion, then we say that the numbers are proportional. a c Example, if = , then a and b are proportional to c and d. b d a c Remember from algebra that, if = , then ad = bc. b d The following proportions are equivalent: a c = b d a b = c d b d = a c c d = a b Theorem: Three or more parallel lines divide trasversals into proportion. l a c m b d n In the picture above, lines l, m, and n are parallel to each other. This means that they divide the two transversals into proportion. In other words, a c = b d a b = c d b d = a c c d = a b Theorem: In any triangle, a line that is paralle to one of the sides divides the other two sides in a proportion. E a c F G b d A B In picture above, FG is parallel to AB, so it divides the other two sides of 4AEB, EA and EB into proportions. In particular, a c = b d b d = a c a b = c d c d = a b Theorem: The bisector of an angle in a triangle divides the opposite side into segments that are proportional to the adjacent side. -

A Rational Expression Is an Expression Which Is the Ratio of Two Polynomials: Example of Rational Expressions: 2X

A Rational Expression is an expression which is the ratio of two polynomials: Example of rational expressions: 2x − 1 1 x3 + 2x − 1 5x2 − 2x + 1 , − , , = 5x2 − 2x + 1 3x2 + 4x − 1 x2 + 1 3x + 2 1 Notice that every polynomial is a rational expression with denominator equal to 1. x2 + 5 For example, x2 + 5 = 1 Think of the relationship between rational expression and polynomial as that be- tween rational numbers and integers. The domain of a rational expression is all real numbers except where the denomi- nator is 0 3x + 4 Example: Find the domain of x2 + 3x − 4 Ans: x2 + 3x − 4 = 0 ) (x + 4)(x − 1) = 0 ) x = −4 or x = 1 Since the denominator, x2 + 3x − 4, of this rational expression is equal to 0 when x = −4 or x = 1, the domain of this rational expression is all real numbers except −4 or 1. In general, to find the domain of a rational expression, set the denominator equal to 0 and solve the equation. The domain of the rational expression is all real numbers except the solution. To Multiply rational expressions, multiply the numerator with the numerator, and multiply denominator with denominator. Cross cancell if possible. Example: x2 + 3x + 2 x2 − 2x + 1 (x + 1)(x + 2) (x − 1)(x − 1) x − 1 · = · = x2 − 1 x2 + 5x + 6 (x − 1)(x + 1) (x + 2)(x + 3) x + 3 To Divide rational expressions, flip the divisor and turn into a multiplication. Example: x2 − 2x + 1 x2 − 1 x2 − 2x + 1 x2 − 16 (x − 1)(x − 1) (x + 4)(x − 4) ÷ = · = · x2 + 5x + 4 x2 − 16 x2 + 5x + 4 x2 − 1 (x + 4)(x + 1) (x + 1)(x − 1) (x − 1) (x − 4) x2 − 5x + 4 = · = (x + 1) (x + 1) x2 + 2x + 1 To Add or Subtract rational expressions, we need to find common denominator by finding the Least Common Multiple, or LCM of the denominators. -

A Tutorial on the Decibel This Tutorial Combines Information from Several Authors, Including Bob Devarney, W1ICW; Walter Bahnzaf, WB1ANE; and Ward Silver, NØAX

A Tutorial on the Decibel This tutorial combines information from several authors, including Bob DeVarney, W1ICW; Walter Bahnzaf, WB1ANE; and Ward Silver, NØAX Decibels are part of many questions in the question pools for all three Amateur Radio license classes and are widely used throughout radio and electronics. This tutorial provides background information on the decibel, how to perform calculations involving decibels, and examples of how the decibel is used in Amateur Radio. The Quick Explanation • The decibel (dB) is a ratio of two power values – see the table showing how decibels are calculated. It is computed using logarithms so that very large and small ratios result in numbers that are easy to work with. • A positive decibel value indicates a ratio greater than one and a negative decibel value indicates a ratio of less than one. Zero decibels indicates a ratio of exactly one. See the table for a list of easily remembered decibel values for common ratios. • A letter following dB, such as dBm, indicates a specific reference value. See the table of commonly used reference values. • If given in dB, the gains (or losses) of a series of stages in a radio or communications system can be added together: SystemGain(dB) = Gain12 + Gain ++ Gainn • Losses are included as negative values of gain. i.e. A loss of 3 dB is written as a gain of -3 dB. Decibels – the History The need for a consistent way to compare signal strengths and how they change under various conditions is as old as telecommunications itself. The original unit of measurement was the “Mile of Standard Cable.” It was devised by the telephone companies and represented the signal loss that would occur in a mile of standard telephone cable (roughly #19 AWG copper wire) at a frequency of around 800 Hz.