Black Hills State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saxon Course 1 Reteachings Lessons 21-30

Name Reteaching 21 Math Course 1, Lesson 21 • Divisibility Last-Digit Tests Inspect the last digit of the number. A number is divisible by . 2 if the last digit is even. 5 if the last digit is 0 or 5. 10 if the last digit is 0. Sum-of-Digits Tests Add the digits of the number and inspect the total. A number is divisible by . 3 if the sum of the digits is divisible by 3. 9 if the sum of the digits is divisible by 9. Practice: 1. Which of these numbers is divisible by 2? A. 2612 B. 1541 C. 4263 2. Which of these numbers is divisible by 5? A. 1399 B. 1395 C. 1392 3. Which of these numbers is divisible by 3? A. 3456 B. 5678 C. 9124 4. Which of these numbers is divisible by 9? A. 6754 B. 8124 C. 7938 Saxon Math Course 1 © Harcourt Achieve Inc. and Stephen Hake. All rights reserved. 23 Name Reteaching 22 Math Course 1, Lesson 22 • “Equal Groups” Word Problems with Fractions What number is __3 of 12? 4 Example: 1. Divide the total by the denominator (bottom number). 12 ÷ 4 = 3 __1 of 12 is 3. 4 2. Multiply your answer by the numerator (top number). 3 × 3 = 9 So, __3 of 12 is 9. 4 Practice: 1. If __1 of the 18 eggs were cracked, how many were not cracked? 3 2. What number is __2 of 15? 3 3. What number is __3 of 72? 8 4. How much is __5 of two dozen? 6 5. -

RATIO and PERCENT Grade Level: Fifth Grade Written By: Susan Pope, Bean Elementary, Lubbock, TX Length of Unit: Two/Three Weeks

RATIO AND PERCENT Grade Level: Fifth Grade Written by: Susan Pope, Bean Elementary, Lubbock, TX Length of Unit: Two/Three Weeks I. ABSTRACT A. This unit introduces the relationships in ratios and percentages as found in the Fifth Grade section of the Core Knowledge Sequence. This study will include the relationship between percentages to fractions and decimals. Finally, this study will include finding averages and compiling data into various graphs. II. OVERVIEW A. Concept Objectives for this unit: 1. Students will understand and apply basic and advanced properties of the concept of ratios and percents. 2. Students will understand the general nature and uses of mathematics. B. Content from the Core Knowledge Sequence: 1. Ratio and Percent a. Ratio (p. 123) • determine and express simple ratios, • use ratio to create a simple scale drawing. • Ratio and rate: solve problems on speed as a ratio, using formula S = D/T (or D = R x T). b. Percent (p. 123) • recognize the percent sign (%) and understand percent as “per hundred” • express equivalences between fractions, decimals, and percents, and know common equivalences: 1/10 = 10% ¼ = 25% ½ = 50% ¾ = 75% find the given percent of a number. C. Skill Objectives 1. Mathematics a. Compare two fractional quantities in problem-solving situations using a variety of methods, including common denominators b. Use models to relate decimals to fractions that name tenths, hundredths, and thousandths c. Use fractions to describe the results of an experiment d. Use experimental results to make predictions e. Use table of related number pairs to make predictions f. Graph a given set of data using an appropriate graphical representation such as a picture or line g. -

Random Denominators and the Analysis of Ratio Data

Environmental and Ecological Statistics 11, 55-71, 2004 Corrected version of manuscript, prepared by the authors. Random denominators and the analysis of ratio data MARTIN LIERMANN,1* ASHLEY STEEL, 1 MICHAEL ROSING2 and PETER GUTTORP3 1Watershed Program, NW Fisheries Science Center, 2725 Montlake Blvd. East, Seattle, WA 98112 E-mail: [email protected] 2Greenland Institute of Natural Resources 3National Research Center for Statistics and the Environment, Box 354323, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 Ratio data, observations in which one random value is divided by another random value, present unique analytical challenges. The best statistical technique varies depending on the unit on which the inference is based. We present three environmental case studies where ratios are used to compare two groups, and we provide three parametric models from which to simulate ratio data. The models describe situations in which (1) the numerator variance and mean are proportional to the denominator, (2) the numerator mean is proportional to the denominator but its variance is proportional to a quadratic function of the denominator and (3) the numerator and denominator are independent. We compared standard approaches for drawing inference about differences between two distributions of ratios: t-tests, t-tests with transformations, permutation tests, the Wilcoxon rank test, and ANCOVA-based tests. Comparisons between tests were based both on achieving the specified alpha-level and on statistical power. The tests performed comparably with a few notable exceptions. We developed simple guidelines for choosing a test based on the unit of inference and relationship between the numerator and denominator. Keywords: ANCOVA, catch per-unit effort, fish density, indices, per-capita, per-unit, randomization tests, t-tests, waste composition 1352-8505 © 2004 Kluwer Academic Publishers 1. -

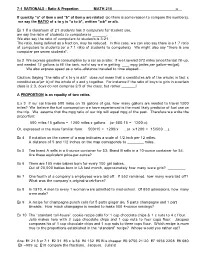

7-1 RATIONALS - Ratio & Proportion MATH 210 F8

7-1 RATIONALS - Ratio & Proportion MATH 210 F8 If quantity "a" of item x and "b" of item y are related (so there is some reason to compare the numbers), we say the RATIO of x to y is "a to b", written "a:b" or a/b. Ex 1 If a classroom of 21 students has 3 computers for student use, we say the ratio of students to computers is . We also say the ratio of computers to students is 3:21. The ratio, being defined as a fraction, may be reduced. In this case, we can also say there is a 1:7 ratio of computers to students (or a 7:1 ratio of students to computers). We might also say "there is one computer per seven students" . Ex 2 We express gasoline consumption by a car as a ratio: If w e traveled 372 miles since the last fill-up, and needed 12 gallons to fill the tank, we'd say we're getting mpg (miles per gallon— mi/gal). We also express speed as a ratio— distance traveled to time elapsed... Caution: Saying “ the ratio of x to y is a:b” does not mean that x constitutes a/b of the whole; in fact x constitutes a/(a+ b) of the whole of x and y together. For instance if the ratio of boys to girls in a certain class is 2:3, boys do not comprise 2/3 of the class, but rather ! A PROPORTION is an equality of tw o ratios. E.x 3 If our car travels 500 miles on 15 gallons of gas, how many gallons are needed to travel 1200 miles? We believe the fuel consumption we have experienced is the most likely predictor of fuel use on the trip. -

Measurement & Transformations

Chapter 3 Measurement & Transformations 3.1 Measurement Scales: Traditional Classifica- tion Statisticians call an attribute on which observations differ a variable. The type of unit on which a variable is measured is called a scale.Traditionally,statisticians talk of four types of measurement scales: (1) nominal,(2)ordinal,(3)interval, and (4) ratio. 3.1.1 Nominal Scales The word nominal is derived from nomen,theLatinwordforname.Nominal scales merely name differences and are used most often for qualitative variables in which observations are classified into discrete groups. The key attribute for anominalscaleisthatthereisnoinherentquantitativedifferenceamongthe categories. Sex, religion, and race are three classic nominal scales used in the behavioral sciences. Taxonomic categories (rodent, primate, canine) are nomi- nal scales in biology. Variables on a nominal scale are often called categorical variables. For the neuroscientist, the best criterion for determining whether a variable is on a nominal scale is the “plotting” criteria. If you plot a bar chart of, say, means for the groups and order the groups in any way possible without making the graph “stupid,” then the variable is nominal or categorical. For example, were the variable strains of mice, then the order of the means is not material. Hence, “strain” is nominal or categorical. On the other hand, if the groups were 0 mgs, 10mgs, and 15 mgs of active drug, then having a bar chart with 15 mgs first, then 0 mgs, and finally 10 mgs is stupid. Here “milligrams of drug” is not anominalorcategoricalvariable. 1 CHAPTER 3. MEASUREMENT & TRANSFORMATIONS 2 3.1.2 Ordinal Scales Ordinal scales rank-order observations. -

The Least Common Multiple of a Quadratic Sequence

The least common multiple of a quadratic sequence Javier Cilleruelo Abstract For any irreducible quadratic polynomial f(x) in Z[x] we obtain the estimate log l.c.m. (f(1); : : : ; f(n)) = n log n + Bn + o(n) where B is a constant depending on f. 1. Introduction The problem of estimating the least common multiple of the ¯rstPn positive integers was ¯rst investigated by Chebyshev [Che52] when he introduced the function ª(n) = pm6n log p = log l.c.m.(1; : : : ; n) in his study on the distribution of prime numbers. The prime number theorem asserts that ª(n) » n, so the asymptotic estimate log l.c.m.(1; : : : ; n) » n is equivalent to the prime number theorem. The analogous asymptotic estimate for any linear polynomial f(x) = ax + b is also known [Bat02] and it is a consequence of the prime number theorem for arithmetic progressions: q X 1 log l.c.m.(f(1); : : : ; f(n)) » n ; (1) Á(q) k 16k6q (k;q)=1 where q = a=(a; b). We address here the problem of estimating log l.c.m.(f(1); : : : ; f(n)) when f is an irreducible quadratic polynomial in Z[x]. When f is a reducible quadratic polynomial the asymptotic estimate is similar to that we obtain for linear polynomials. This case is studied in section x4 with considerably less e®ort than the irreducible case. We state our main theorem. Theorem 1. For any irreducible quadratic polynomial f(x) = ax2 + bx + c in Z[x] we have log l.c.m. -

Eureka Math™ Tips for Parents Module 2

Grade 6 Eureka Math™ Tips for Parents Module 2 The chart below shows the relationships between various fractions and may be a great Key Words tool for your child throughout this module. Greatest Common Factor In this 19-lesson module, students complete The greatest common factor of two whole numbers (not both zero) is the their understanding of the four operations as they study division of whole numbers, division greatest whole number that is a by a fraction, division of decimals and factor of each number. For operations on multi-digit decimals. This example, the GCF of 24 and 36 is 12 expanded understanding serves to complete because when all of the factors of their study of the four operations with positive 24 and 36 are listed, the largest rational numbers, preparing students for factor they share is 12. understanding, locating, and ordering negative rational numbers and working with algebraic Least Common Multiple expressions. The least common multiple of two whole numbers is the least whole number greater than zero that is a What Came Before this Module: multiple of each number. For Below is an example of how a fraction bar model can be used to represent the Students added, subtracted, and example, the LCM of 4 and 6 is 12 quotient in a division problem. multiplied fractions and decimals (to because when the multiples of 4 and the hundredths place). They divided a 6 are listed, the smallest or first unit fraction by a non-zero whole multiple they share is 12. number as well as divided a whole number by a unit fraction. -

Proportions: a Ratio Is the Quotient of Two Numbers. for Example, 2 3 Is A

Proportions: 2 A ratio is the quotient of two numbers. For example, is a ratio of 2 and 3. 3 An equality of two ratios is a proportion. For example, 3 15 = is a proportion. 7 45 If two sets of numbers (none of which is 0) are in a proportion, then we say that the numbers are proportional. a c Example, if = , then a and b are proportional to c and d. b d a c Remember from algebra that, if = , then ad = bc. b d The following proportions are equivalent: a c = b d a b = c d b d = a c c d = a b Theorem: Three or more parallel lines divide trasversals into proportion. l a c m b d n In the picture above, lines l, m, and n are parallel to each other. This means that they divide the two transversals into proportion. In other words, a c = b d a b = c d b d = a c c d = a b Theorem: In any triangle, a line that is paralle to one of the sides divides the other two sides in a proportion. E a c F G b d A B In picture above, FG is parallel to AB, so it divides the other two sides of 4AEB, EA and EB into proportions. In particular, a c = b d b d = a c a b = c d c d = a b Theorem: The bisector of an angle in a triangle divides the opposite side into segments that are proportional to the adjacent side. -

A Rational Expression Is an Expression Which Is the Ratio of Two Polynomials: Example of Rational Expressions: 2X

A Rational Expression is an expression which is the ratio of two polynomials: Example of rational expressions: 2x − 1 1 x3 + 2x − 1 5x2 − 2x + 1 , − , , = 5x2 − 2x + 1 3x2 + 4x − 1 x2 + 1 3x + 2 1 Notice that every polynomial is a rational expression with denominator equal to 1. x2 + 5 For example, x2 + 5 = 1 Think of the relationship between rational expression and polynomial as that be- tween rational numbers and integers. The domain of a rational expression is all real numbers except where the denomi- nator is 0 3x + 4 Example: Find the domain of x2 + 3x − 4 Ans: x2 + 3x − 4 = 0 ) (x + 4)(x − 1) = 0 ) x = −4 or x = 1 Since the denominator, x2 + 3x − 4, of this rational expression is equal to 0 when x = −4 or x = 1, the domain of this rational expression is all real numbers except −4 or 1. In general, to find the domain of a rational expression, set the denominator equal to 0 and solve the equation. The domain of the rational expression is all real numbers except the solution. To Multiply rational expressions, multiply the numerator with the numerator, and multiply denominator with denominator. Cross cancell if possible. Example: x2 + 3x + 2 x2 − 2x + 1 (x + 1)(x + 2) (x − 1)(x − 1) x − 1 · = · = x2 − 1 x2 + 5x + 6 (x − 1)(x + 1) (x + 2)(x + 3) x + 3 To Divide rational expressions, flip the divisor and turn into a multiplication. Example: x2 − 2x + 1 x2 − 1 x2 − 2x + 1 x2 − 16 (x − 1)(x − 1) (x + 4)(x − 4) ÷ = · = · x2 + 5x + 4 x2 − 16 x2 + 5x + 4 x2 − 1 (x + 4)(x + 1) (x + 1)(x − 1) (x − 1) (x − 4) x2 − 5x + 4 = · = (x + 1) (x + 1) x2 + 2x + 1 To Add or Subtract rational expressions, we need to find common denominator by finding the Least Common Multiple, or LCM of the denominators. -

A Tutorial on the Decibel This Tutorial Combines Information from Several Authors, Including Bob Devarney, W1ICW; Walter Bahnzaf, WB1ANE; and Ward Silver, NØAX

A Tutorial on the Decibel This tutorial combines information from several authors, including Bob DeVarney, W1ICW; Walter Bahnzaf, WB1ANE; and Ward Silver, NØAX Decibels are part of many questions in the question pools for all three Amateur Radio license classes and are widely used throughout radio and electronics. This tutorial provides background information on the decibel, how to perform calculations involving decibels, and examples of how the decibel is used in Amateur Radio. The Quick Explanation • The decibel (dB) is a ratio of two power values – see the table showing how decibels are calculated. It is computed using logarithms so that very large and small ratios result in numbers that are easy to work with. • A positive decibel value indicates a ratio greater than one and a negative decibel value indicates a ratio of less than one. Zero decibels indicates a ratio of exactly one. See the table for a list of easily remembered decibel values for common ratios. • A letter following dB, such as dBm, indicates a specific reference value. See the table of commonly used reference values. • If given in dB, the gains (or losses) of a series of stages in a radio or communications system can be added together: SystemGain(dB) = Gain12 + Gain ++ Gainn • Losses are included as negative values of gain. i.e. A loss of 3 dB is written as a gain of -3 dB. Decibels – the History The need for a consistent way to compare signal strengths and how they change under various conditions is as old as telecommunications itself. The original unit of measurement was the “Mile of Standard Cable.” It was devised by the telephone companies and represented the signal loss that would occur in a mile of standard telephone cable (roughly #19 AWG copper wire) at a frequency of around 800 Hz. -

Fundamental Arithmetic

FUNDAMENTAL ARITHMETIC Prime Numbers Prime numbers are any whole numbers greater than 1 that can only be divided by 1 and itself. Below is the list of all prime numbers between 1 and 100: 2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29 31 37 41 43 47 53 59 61 67 71 73 79 83 89 97 Prime Factorization Prime factorization is the process of changing non-prime (composite) numbers into a product of prime numbers. Below is the prime factorization of all numbers between 1 and 20. 1 is unique 6 = 2 ∙ 3 11 is prime 16 = 2 ∙ 2 ∙ 2 ∙ 2 2 is prime 7 is prime 12 = 2 ∙ 2 ∙ 3 17 is prime 3 is prime 8 = 2 ∙ 2 ∙ 2 13 is prime 18 = 2 ∙ 3 ∙ 3 4 = 2 ∙ 2 9 = 3 ∙ 3 14 = 2 ∙ 7 19 is prime 5 is prime 10 = 2 ∙ 5 15 = 3 ∙ 5 20 = 2 ∙ 2 ∙ 5 Divisibility By using these divisibility rules, you can easily test if one number can be evenly divided by another. A Number is Divisible By: If: Examples 2 The last digit is 5836 divisible by two 583 ퟔ ퟔ ÷ 2 = 3, Yes 3 The sum of the digits is 1725 divisible by three 1 + 7 + 2 + 5 = ퟏퟓ ퟏퟓ ÷ 3 = 5, Yes 5 The last digit ends 885 in a five or zero 88 ퟓ The last digit ends in a five, Yes 10 The last digit ends 7390 in a zero 739 ퟎ The last digit ends in a zero, Yes Exponents An exponent of a number says how many times to multiply the base number to itself. -

3Understanding Addition and Subtraction

Understanding Addition 3 and Subtraction Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. SECTION Understanding Addition and 3.3 Subtraction of Fractions Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. What do you think? • Why do we need a common denominator to add (or subtract) two fractions ? • What pictorial representations can we use for addition and subtraction with fractions? 3 Understanding Addition and Subtraction of Fractions There are many algorithms that enable us to manipulate fractions quickly : I is simply not enough for an elementary teacher to know how to compute. It is crucial that the teacher also know the whys behind the hows and can use a variety of representations to explain them. 4 Investigation 3.3a – Using Fraction Models to Understand Addition of Fractions Using the area model, the length model, or the set model, determine the sum of and then explain why we need to find a common denominator in order to add fractions. 5 Investigation 3.3a – Discussion This is an excellent place to demonstrate the role of manipulatives. Using pattern blocks How might you use pattern blocks to add and (see Figure 3.8)? Figure 3.8 6 Investigation 3.3a – Discussion continued If we let the hexagon represent 1, then the trapezoid is the parallelogram is and the triangle is Using the notion of addition as combining, we can combine the two, and we have We could be humorous and say that parallelogram + trapezoid = baby carriage! The key question , though, is to determine the value of this amount . The solution lies in realizing that to name an amount with a fraction, we must have equal - size parts.