CRM Leadership Development Practice: Developing a Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crew Resource Management in Healthcare

FLYING LESSONS: CREW RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN HEALTHCARE Authored by: Colin Konschak, FACHE, CEO Blake Smith, Principal www.divurgent.com © Divurgent 2017-2018 INTRODUCTION Patient safety has come under closer scrutiny in recent years and experts agree that human factors are major contributors to adverse events in healthcare. In its1999 landmark report, “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System,” the Institute of Medicine (IOM) stated that anywhere from 44,000 to 98,000 patients die each year as a result of medical errors at an estimated annual cost of $29 billion.i Medical errors, two-thirds of which are preventable, are the eighth leading cause of death in the U.S. each year.ii As medicine relies on increasingly complex technologies, this problem will only intensify. For example, The New York Times recently conducted a study that found an alarming number of injuries related to radiation therapy. The injuries, which should have been avoidable, were caused by faulty programming, poor safety procedures, software flaws that should have been recognized, and inadequate staffing and training.iii Like medicine, aviation relies on teams of experts working together to carry out complex procedures that, if not executed properly, can have serious consequences. If 98,000 people died in plane crashes each year, it would be the equivalent of a fatal jet crash – 268 passengers – every day. Airlines, however, have taken steps to prevent such catastrophes and health care providers are taking note. FOLLOWING AVIATION’S LEAD In 1977, two Boeing 747s collided on a runway in the Canary Islands, killing 582 people. -

Aerosafety World November 2009

AeroSafety WORLD DOUSING THE FLAMES FedEx’s automatic system CRM FAILURE Black hole approach UPSET TRAINING Airplane beats simulators IASS REPORT 777 power rollback, more TRAGEDY AS INSPIRATION JAPAN Airlines’ safeTY CENTER THE JOURNAL OF FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION NOVEMBER 2009 “Cessna is committed to providing the latest safety information to our customers, and that’s why we provide each new Citation owner with an FSF Aviation Department Tool Kit.” — Will Dirks, VP Flight Operations, Cessna Aircraft Co. afety tools developed through years of FSF aviation safety audits have been conveniently packaged for your flight crews and operations personnel. These tools should be on your minimum equipment list. The FSF Aviation Department Tool Kit is such a valuable resource that Cessna Aircraft Co. provides each new Citation owner with a copy. One look at the contents tells you why. Templates for flight operations, safety and emergency response manuals formatted for easy adaptation Sto your needs. Safety-management resources, including an SOPs template, CFIT risk assessment checklist and approach-and-landing risk awareness guidelines. Principles and guidelines for duty and rest schedul- ing based on NASA research. Additional bonus CDs include the Approach and Landing Accident Reduction Tool Kit; Waterproof Flight Operations (a guide to survival in water landings); Operator’sMEL Flight Safety Handbook; item Turbofan Engine Malfunction Recognition and Response; and Turboprop Engine Malfunction Recognition and Response. Here’s your all-in-one collection of flight safety tools — unbeatable value for cost. FSF member price: US$750 Nonmember price: US$1,000 Quantity discounts available! For more information, contact: Namratha Apparao, + 1 703 739-6700, ext. -

The Most Important Aviation System: the Human Team and Decision Making in the Modern Cockpit

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2004 The Most Important Aviation System: The Human Team and Decision Making in the Modern Cockpit John Cody Allee University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Allee, John Cody, "The Most Important Aviation System: The Human Team and Decision Making in the Modern Cockpit. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1820 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by John Cody Allee entitled "The Most Important Aviation System: The Human Team and Decision Making in the Modern Cockpit." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Aviation Systems. Robert B. Richards, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Ralph D. Kimberlin, George W. Garrison Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council I am submitting herewith a thesis written by John Cody Allee entitled "The Most Important Aviation System: The Human Team and Decision Making in the Modern Cockpit. -

International Journal of Applied Aviation Studies Federal Aviation Administration

2010 International Journal of Applied Aviation Studies Federal Aviation Administration Volume 10, Number 1 A publication of the FAA Academy International Journal of Applied Aviation Studies A Publication of the FAA Academy Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Volume 10, Number 1 2010 REVIEW PROCESS 1 The Federal Aviation Administration Academy provides traceability and over- sight for each step of the International Journal of Applied Aviation Studies (IJAAS). IJAAS is a peer-reviewed publication, enlisting the support of an international pan- el of consulting editors. Each consulting editor was chosen for his or her expertise in one or more areas of interest in aviation. Using the blind-review process, three or more consulting editors are selected to appraise each article, judging whether or not it meets the requirements of this publication. In addition to an overall appraisal, a Likert scale is used to measure attitudes regarding individual segments of each article. Articles that are accepted are those that were approved by a majority of judges. Articles that do not meet IJAAS requirements for publication are released back to their author or authors. Individuals wishing to obtain a copy of the IJAAS on CD may contact Kay Ch- isholm by email at [email protected], or by telephone at (405) 954-3264, or by writing to the following address: International Journal of Applied Aviation Studies Kay Chisholm AMA-800 PO Box 25082 Oklahoma City, OK 73125 International Journal of Applied Aviation Studies Volume 10, Number 1 ISSN Number: 1546-3214 Copyright © 2010, FAA Academy 1st Printing August, 2010 The International Journal of Applied Aviation Studies 1 POLICY AND DISCLAIMERS Policy Statement: The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Academy strongly supports academic freedom and a researcher’s right to publish; therefore, the Fed- eral Aviation Administration Academy as an institution does not endorse the view- point or guarantee the technical correctness of any of the articles in this journal. -

Maintenance Resource Management Programs

FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION OCTOBER 2002 FLIGHT SAFETY DIGEST Maintenance Resource Management Programs Provide Tools for Reducing Human Error FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION For Everyone Concerned With the Safety of Flight Flight Safety Digest Officers and Staff Vol. 21 No. 10 October 2002 Hon. Carl W. Vogt Chairman, Board of Governors Stuart Matthews In This Issue President and CEO Robert H. Vandel Maintenance Resource Management Executive Vice President Programs Provide Tools for Reducing 1 James S. Waugh Jr. Human Error Treasurer The programs include a variety of initiatives to identify and ADMINISTRATIVE reduce human error in aviation maintenance. Specialists Ellen Plaugher applaud the goal, but some say that the programs are not Special Events and Products Manager achieving sufficient progress. Linda Crowley Horger Manager, Support Services Data Show 32 Accidents in 2001 Among FINANCIAL 16 Crystal N. Phillips Western-built Large Commercial Jets Director of Finance and Administration Twenty of the accidents were classified as hull-loss accidents. Millicent Wheeler Data show an accident rate in 2001 of 1.75 per 1 million Accountant departures and a hull-loss/fatal accident rate of 1.17 per TECHNICAL 1 million departures. James M. Burin Director of Technical Programs Study Analyzes Differences in Joanne Anderson 23 Technical Programs Specialist Rotating-shift Schedules Louis A. Sorrentino III The report on the study, conducted by the U.S. Federal Managing Director of Internal Evaluation Programs Aviation Administration, said that changing shift rotation for Robert Feeler air traffic controllers probably would not result in improved Q-Star Program Administrator sleep. Robert Dodd, Ph.D. Manager, Data Systems and Analysis B-767 Flap Component Separates Darol V. -

Advanced Technology Aircraft Safety Survey Report

Department of Transport and Regional Dedvelopment Bureau of Air Safety Investigation Advanced Technology Aircraft Safety Survey Report Released by the Secretary of the Department of Transport and Regional Development under the provision of Section 19CU of part 2A of the Air navigation Act (1920). When the Bureau makes recommendations as a result of its investigations or research, safety, (in accordance with its charter), is its primary consideration. However, the Bureau fully recognises that the implementation of recommendations arising from its investigations will in some cases incur a cost to the industry. Readers should note that the information in BAS1 reports is provided to promote aviation safety: in no case is it intended to imply blame or liability. ISBN 0 642 27456 8 June 1998 This report was produced by the Bureau of Air Safety Investigation (BASI), PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608. Readers are advised that the Bureau investigates for the sole purpose of enhancing aviation safety. Consequently, Bureau reports are confined to matters of safety significance and may be misleading if used for any other purpose. As BASI believes that safety information is of greatest value if it is passed on for the use of others, readers are encouraged to copy or reprint for further distribution, acknowledging BASI as the source. CONTENTS ... CONTENTS 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii ... ABBREVIATIONS Vlll SYNOPSIS ix INTRODUCTION 1 Definitions 1 Background 1 Scope 2 Objectives 2 Method 2 Confidentiality 3 Archiving 3 Statistical analysis 3 Report - figure -

Flight-Crew Human Factors Handbook

Intelligence, Strategy and Policy Flight-crew human factors handbook CAP 737 CAP 737 Published by the Civil Aviation Authority, 2014 Civil Aviation Authority, Aviation House, Gatwick Airport South, West Sussex, RH6 0YR. You can copy and use this text but please ensure you always use the most up to date version and use it in context so as not to be misleading, and credit the CAA. Enquiries regarding the content of this publication should be addressed to: Intelligence, Strategy and Policy Aviation House Gatwick Airport South Crawley West Sussex England RH6 0YR The latest version of this document is available in electronic format at www.caa.co.uk, where you may also register for e-mail notification of amendments. December 2016 Page 2 CAP 737 Contents Contents Contributors 5 Glossary of acronyms 7 Introduction to Crew Resource Management (CRM) and Threat and Error Management (TEM) 10 Section A. Human factors knowledge and application 15 Section A, Part 1. The Individual (summary) 17 Section A, Part 1, Chapter 1. Information processing 18 Chapter 2. Perception 22 Chapter 3. Attention 30 Chapter 4. Vigilance and monitoring 33 Chapter 5. Human error, skill, reliability,and error management 39 Chapter 6. Workload 55 Chapter 7. Surprise and startle 64 Chapter 8. Situational Awareness (SA) 71 Chapter 9. Decision Making 79 Chapter 9, Sub-chapter 1. Rational (classical) decision making 80 Chapter 9, Sub-chapter 2. Quicker decision making mechanisms and shortcuts 88 Chapter 9, Sub-chapter 3. Very fast (intuitive) decision-making 96 Chapter 10. Stress in Aviation 100 Chapter 11. Sleep and fatigue 109 Chapter 12. -

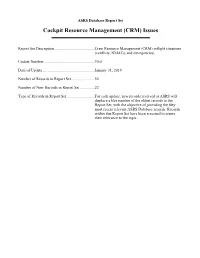

ASRS Database Report Set Cockpit Resource Management (CRM) Issues

ASRS Database Report Set Cockpit Resource Management (CRM) Issues Report Set Description .........................................Crew Resource Management (CRM) inflight situations (conflicts, NMACs, and emergencies). Update Number ....................................................30.0 Date of Update .....................................................January 31, 201 9 Number of Records in Report Set ........................50 Number of New Records in Report Set ...............22 Type of Records in Report Set.............................For each update, new records received at ASRS will displace a like number of the oldest records in the Report Set, with the objective of providing the fifty most recent relevant ASRS Database records. Records within this Report Set have been screened to assure their relevance to the topic. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Ames Research Center Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000 TH: 262-7 MEMORANDUM FOR: Recipients of Aviation Safety Reporting System Data SUBJECT: Data Derived from ASRS Reports The attached material is furnished pursuant to a request for data from the NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS). Recipients of this material are reminded when evaluating these data of the following points. ASRS reports are submitted voluntarily. Such incidents are independently submitted and are not corroborated by NASA, the FAA or NTSB. The existence in the ASRS database of reports concerning a specific topic cannot, therefore, be used to infer the prevalence of that problem within the National Airspace System. Information contained in reports submitted to ASRS may be clarified by further contact with the individual who submitted them, but the information provided by the reporter is not investigated further. Such information represents the perspective of the specific individual who is describing their experience and perception of a safety related event. -

Flight Crew Leadership (Cortes Jan2011)

Flight Crew Leadership By Antonio I. Cortés January 2011 Abstract The efficiency and safety of aircraft operations can be traced back to the use of influence by leaders to affect the behavior and attitude of subordinates. Leadership skills are not genetic; they are learned through education and honed by a professional commitment to self- improvement. Although many flight deck management actions are dictated by standard operating procedures and technical training, the leadership functions of captains are considered to be different from management acts and should be used to foster a working climate that encourages respectful participation in the captain’s authority. By referencing ten “best practices” of leadership, captains can set and control the appropriate authority gradients with subordinates in order to achieve synergy out of a crew. Ultimately, each captain must pursue an authentic leadership style through self-awareness and by reflecting on how he or she values concern for task accomplishment versus concern for crewmembers, as illustrated by the Blake and Mouton Leadership Grid. Flight Crew Leadership – Cortés – January 2011 2 We need leaders! Not just political leaders. We need leaders in every field, in every institution, in all kinds of situations. We need to be educating our young people to be leaders. And unfortunately, that’s fallen out of fashion.1 David McCullough U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom winner. Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner. Contents Leadership Philosophy Captain’s Authority Transcockpit Authority Gradients Actions of Capable Leaders Authentic Leadership Actions of Effective Followers Learning Checklist • After Reading this paper you should be able to: ■ Provide a personalized definition of leadership and of followership. -

Human Factors in Aviation: Crm (Crew Resource Management)

Articles Papeles del Psicólogo / Psychologist Papers , 2018. Vol. 39(3), pp. 191-199 https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2018.2870 http://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es http:// www.psychologistpapers.com HUMAN FACTORS IN AVIATION: CRM (CREW RESOURCE MANAGEMENT) Daniel Muñoz-Marrón Piloto del Ejército del Aire (Ministerio de Defensa). Psicólogo Especialista en Psicología Clínica Uno de los campos aplicados a los que más ha contribuido la ciencia psicológica es, sin lugar a dudas, el de la aviación. El análisis y estudio de los factores humanos constituye actualmente uno de los puntos fuertes en el sector aeronáutico de cara a la reducción de los accidentes aéreos. Desde su aparición en 1979, los programas de Gestión de Recursos de la Tripulación (CRM) han sido una de las herramientas que con mayor éxito han gestionado el denominado “error humano”. El presente artículo realiza un breve recorrido por la historia de estos programas globales de entrenamiento que suponen uno de los grandes logros de la Psicología Aplicada. Palabras clave: Gestión de Recursos de la Tripulación (CRM), Entrenamiento de vuelo, Factores humanos, Psicología de la Aviación, Seguridad Aérea. Without a doubt, aviation is one of the applied fields to which psychological science has most contributed. The analysis and study of human factors is currently one of the strong points in the aeronautical sector in reducing accidents in aviation. Since their appearance in 1979, crew resource management (CRM) programs have been one of the most successful tools for dealing with what is known as “human error”. This paper gives a brief tour through the history of these global training programs that represent one of the great achievements of applied psychology. -

An Improved Simulated Annealing Search

The Activated Failures of Human-Automation Interactions on the Flight Deck * Wen-Chin Li1**, Matthew Greaves1, Davide Durando1, John J. H. Lin2 1Safety and Accident Investigation Center, Air Transport Department, Cranfield, Bedford, MK430AB, Cranfield University, United Kingdom 2 Institute of Education National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan ABSTRACT Cockpit automation has been developed to reduce pilots’ workload and increase pilots’ performance. However, previous studies have demonstrated that failures of automated systems have significantly impaired pilots’ situational awareness. The increased application of automation and the trend of pilots to rely on automation have changed pilot’s role from an operator to a supervisor in the cockpit. Based on the analysis of 257 ASRS reports, the result demonstrated that pilots represent the last line of defence during automation failures, though sometimes pilots did commit active failures combined with automation-induced human errors. Current research found that automation breakdown has direct associated with 4 categories of precondition of unsafe acts, including ‘adverse mental states’, ‘CRM’, ‘personal readiness’, and ‘technology environment’. Furthermore, the presence of ‘CRM’ almost 3.6 times, 12.7 times, 2.9 times, and 4 times more likely to occur concomitant failures in the categories of ‘decision-errors’, ‘skill-based error’, ‘perceptual errors’, and ‘violations’. Therefore, CRM is the most critical category for developing intervention of Human-Automation Interaction (HAI) issues to improve aviation safety. The study of human factors in automated cockpit is critical to understand how incidents/accidents had developed and how they could be prevented. Future HAI research should continue to increase the reliability of automation on the flight deck, develop backup systems for the occasional failures of cockpit automation, and train flight crews with competence of CRM skills in response to automation breakdowns. -

Crew Resource Management Application in Commercial Aviation

Available online at http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jate Journal of Aviation Technology and Engineering 3:2 (2014) 2–13 Crew Resource Management Application in Commercial Aviation Frank Wagener Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University David C. Ison Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University–Worldwide Abstract The purpose of this study was to extend previous examinations of commercial multi-crew airplane accidents and incidents to evaluate the Crew Resource Management (CRM) application as it relates to error management during the final approach and landing phase of flight. With data obtained from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), a x2 test of independence was performed to examine if there would be a statistically significant relationship between airline management practices and CRM-related causes of accidents/incidents. Between 2002 and 2012, 113 accidents and incidents occurred in the researched segments of flight. In total, 57 (50 percent) accidents/incidents listed a CRM-related casual factor or included a similar commentary within the analysis section of the investigation report. No statistically significant relationship existed between CRM-related accidents/incidents About the Authors Frank Wagener currently works for Aviation Performance Solutions LLC (APS), dba APS Emergency Maneuver Training, based at the Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport in Mesa, Arizona. APS offers comprehensive LOC-I solutions via industry-leading, computer-based, on-aircraft, and advanced full-flight simulator upset recovery and prevention training programs. Wagener spent over 20 years in the German Air Force flying fighter and fighter training aircraft and retired in 2011. He flew and instructed in Germany, Canada, and the United States.