The Co-Evolution of Concepts and Motivation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Discourse Analysis Study Questions

5th edition This guide contains suggested answers for the Study Questions, with answers and tutorials for the Tasks in each chapter of The Study of Language (5th edition). This guide contains suggested answers for the Study Questions, with answers and tutorials for the Tasks in each chapter of The Study of Language (5th edition). © 2014 George Yule 2 Contents 1 The origins of language ................................................................................................ 4 2 Animals and human language ................................................................................... 11 3 The sounds of language ............................................................................................. 18 4 The sound patterns of language ............................................................................... 22 5 Word formation............................................................................................................. 26 6 Morphology ................................................................................................................... 32 7 Grammar ....................................................................................................................... 36 8 Syntax ............................................................................................................................ 41 9 Semantics ..................................................................................................................... 47 10 Pragmatics ................................................................................................................. -

Coordination, Indirect Speech, and Self-Conscious Emotions

The Psychology of Common Knowledge: Coordination, Indirect Speech, and Self-Conscious Emotions The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Thomas, Kyle. 2015. The Psychology of Common Knowledge: Coordination, Indirect Speech, and Self-Conscious Emotions. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17467482 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Psychology of Common Knowledge: Coordination, Indirect Speech, and Self-conscious Emotions A dissertation presented by Kyle Andrew Thomas to The Department of Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Psychology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Kyle Andrew Thomas All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Steven Pinker Kyle Andrew Thomas The Psychology of Common Knowledge: Coordination, Indirect Speech, and Self-conscious Emotions ABSTRACT The way humans cooperate is unparalleled in the animal kingdom, and coordination plays an important role in human cooperation. Common knowledge—an infinite recursion of shared mental states, such that A knows X, A knows that B knows X, A knows that B knows that A knows X, ad infinitum—is strategically important in facilitating coordination. Common knowledge has also played an important theoretical role in many fields, and has been invoked to explain a staggering diversity of social phenomena. -

The False Allure of Group Selection | Conversation | Edge 19/06/2012 16:34

The False Allure Of Group Selection | Conversation | Edge 19/06/2012 16:34 To arrive at the edge of the world's knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves. Get Edge.org by Email Tuesday, Jun 19, 2012 HOME CONVERSATIONS ANNUAL QUESTION EVENTS NEWS LIBRARY ABOUT THE FALSE ALLURE OF GROUP SELECTION WHAT'S RELATED An Edge Original Essay People Steven Pinker [6.18.12] Steven Pinker Johnstone Family Professor, Department Of... Stewart Brand Founder, The Whole Earth Catalog; Co- founder, The... Conversations at Edge [+] A History of Violence Edge Master Class 2011 By Steven Pinker [9.27.11] Language and Human Nature A talk by Steven Pinker [9.30.09] The Stuff of Thought "The Experiment Marathon": A conversation [photo credit: Max Gerber] By Marcy Kahan, Steven Pinker [10.14.07] "I am often asked whether I agree with the new group selectionists, and the questioners are always Preface to Dangerous Ideas surprised when I say I do not. After all, group selection sounds like a reasonable extension of By Steven Pinker [12.31.06] evolutionary theory and a plausible explanation of the social nature of humans. Also, the group selectionists tend to declare victory, and write as if their theory has already superseded a narrow, reductionist dogma that selection acts only at the level of genes. In this essay, I'll explain why I think Beyond Edge that this reasonableness is an illusion. The more carefully you think about group selection, the less sense Stevenpinker.com it makes, and the more poorly it fits the facts of human psychology and history." Books [+] STEVEN PINKER is a Harvard College Professor and Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology; Harvard University. -

Pinker the Moral Instinct

January 13, 2008 The Moral Instinct By STEVEN PINKER Which of the following people would you say is the most admirable: Mother Teresa, Bill Gates or Norman Borlaug? And which do you think is the least admirable? For most people, it’s an easy question. Mother Teresa, famous for ministering to the poor in Calcutta, has been beatified by the Vatican, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and ranked in an American poll as the most admired person of the 20th century. Bill Gates, infamous for giving us the Microsoft dancing paper clip and the blue screen of death, has been decapitated in effigy in “I Hate Gates” Web sites and hit with a pie in the face. As for Norman Borlaug . who the heck is Norman Borlaug? Yet a deeper look might lead you to rethink your answers. Borlaug, father of the “Green Revolution” that used agricultural science to reduce world hunger, has been credited with saving a billion lives, more than anyone else in history. Gates, in deciding what to do with his fortune, crunched the numbers and determined that he could alleviate the most misery by fighting everyday scourges in the developing world like malaria, diarrhea and parasites. Mother Teresa, for her part, extolled the virtue of suffering and ran her well-financed missions accordingly: their sick patrons were offered plenty of prayer but harsh conditions, few analgesics and dangerously primitive medical care. It’s not hard to see why the moral reputations of this trio should be so out of line with the good they have done. -

Language As a Window Into Human Nature Ebook, Epub

THE STUFF OF THOUGHT:: LANGUAGE AS A WINDOW INTO HUMAN NATURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Steven Pinker | 512 pages | 30 May 2008 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141015477 | English | London, United Kingdom The Stuff of Thought:: Language as a Window into Human Nature PDF Book I suppose that PInker argues throughout from a evolutionary psychological view point, but this becomes most clear in the second to last chapter and maybe it is simply because I am still very critical towards that school of thought, but to my mind the second to last chapter is the least convincing. Pinker is known for his wide-ranging explorations of human nature and its relevance to language, history, morality, politics, and everyday life. An extreme nativist holds that the language we use for thought is totally predetermined. This isn't a knee-jerk reaction from a sociologist; socio-biological explanations are generally examples of people reading their own interpretations of the social world, and how it "ought" to be, back into "history" and saying that it's natural. As such these two have been my least favourite of his books. Is it a construction of our language? He seems to think it has a lot to do with verbs. Through this lens, Pinker asks questions such as "What does the peculiar syntax of swearing tell us about ourselves? First we hear of academics that make claims that imply that nearly all words are innate to the human mind, and are inborn as part of our genetic makeup i. He argues with everyone! We hear of psychology, cultural practices, and evolution. -

Review of the Stuff of Thought by Steven Pinker (2008)

Review of The Stuff of Thought by Steven Pinker (2008) Michael Starks ABSTRACT I start with some famous comments by the philosopher (psychologist) Ludwig Wittgenstein because Pinker shares with most people (due to the default settings of our evolved innate psychology) certain prejudices about the functioning of the mind and because Wittgenstein offers unique and profound insights into the workings of language, thought and reality (which he viewed as more or less coextensive) not found anywhere else. The last quote is the only reference Pinker makes to Wittgenstein in this volume, which is most unfortunate considering that he was one of the most brilliant and original analysts of language. In the last chapter, using the famous metaphor of Plato’s cave, he beautifully summarizes the book with an overview of how the mind (language, thought, intentional psychology) –a product of blind selfishness, moderated only slightly by automated altruism for close relatives carrying copies of our genes--works automatically, but tries to end on an upbeat note by giving us hope that we can nevertheless employ its vast capabilities to cooperate and make the world a decent place to live. Pinker is certainly aware of but says little about the fact that far more about our psychology is left out than included. Among windows into human nature that are left out or given minimal attention are math and geometry, music and sounds, images, events and causality, ontology (classes of things), dispositions (believing, thinking, judging, intending etc.) and the rest of intentional psychology of action, neurotransmitters and entheogens, spiritual states (e.g, satori and enlightenment, brain stimulation and recording, brain damage and behavioral deficits and disorders, games and sports, decision theory (incl. -

Human Emotions: an Evolutionary Psychological Perspective

EMR0010.1177/1754073914565518Emotion ReviewAl-Shawaf et al. Evolutionary Psychology of the Emotions 565518research-article2015 ARTICLE Emotion Review 1 –14 © The Author(s) 2015 ISSN 1754-0739 DOI: 10.1177/1754073914565518 Human Emotions: An Evolutionary er.sagepub.com Psychological Perspective Laith Al-Shawaf Daniel Conroy-Beam Kelly Asao David M. Buss Department of Psychology, The University of Texas at Austin, USA Abstract Evolutionary approaches to the emotions have traditionally focused on a subset of emotions that are shared with other species, characterized by distinct signals, and designed to solve a few key adaptive problems. By contrast, an evolutionary psychological approach (a) broadens the range of adaptive problems emotions have evolved to solve, (b) includes emotions that lack distinctive signals and are unique to humans, and (c) synthesizes an evolutionary approach with an information-processing perspective. On this view, emotions are superordinate mechanisms that evolved to coordinate the activity of other programs in the solution of adaptive problems. We illustrate the heuristic value of this approach by furnishing novel hypotheses for disgust and sexual arousal and highlighting unexplored areas of research. Keywords basic emotion, coordinating mechanisms, disgust, emotion, evolutionary psychology, sexual arousal, superordinate mechanisms Beginning with Darwin (1872/2009), evolutionary approaches even by evolutionary theorists. Differential reproductive success, to the emotions have focused on a delimited subset of psycho- not differential survival success, is the “engine” of evolution by logical phenomena. They have largely centered on emotions selection. Consequently, emotions may have evolved to solve that solve a subset of adaptive problems, carry distinctive uni- adaptive problems in a broad range of domains tributary to repro- versal signals, are universally recognized by conspecifics, and ductive success. -

Evans-Levinson BBS 2009.Pdf

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2009) 32, 429–492 doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999094X The myth of language universals: Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science Nicholas Evans Department of Linguistics, Research School of Asian and Pacific Studies, Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia [email protected] http://rspas.anu.edu.au/people/personal/evann_ling.php Stephen C. Levinson Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Wundtlaan 1, NL-6525 XD Nijmegen, The Netherlands; and Radboud University, Department of Linguistics, Nijmegen, The Netherlands [email protected] http://www.mpi.nl/Members/StephenLevinson Abstract: Talk of linguistic universals has given cognitive scientists the impression that languages are all built to a common pattern. In fact, there are vanishingly few universals of language in the direct sense that all languages exhibit them. Instead, diversity can be found at almost every level of linguistic organization. This fundamentally changes the object of enquiry from a cognitive science perspective. This target article summarizes decades of cross-linguistic work by typologists and descriptive linguists, showing just how few and unprofound the universal characteristics of language are, once we honestly confront the diversity offered to us by the world’s 6,000 to 8,000 languages. After surveying the various uses of “universal,” we illustrate the ways languages vary radically in sound, meaning, and syntactic organization, and then we examine in more detail the core grammatical machinery of recursion, constituency, and grammatical relations. Although there are significant recurrent patterns in organization, these are better explained as stable engineering solutions satisfying multiple design constraints, reflecting both cultural-historical factors and the constraints of human cognition. -

Suicidal Utopian Delusions in the 21St Century

Suicidal Utopian Delusions in the 21st Century Philosophy, Human Nature and the Collapse of Civilization Articles and Reviews 2006-2019 4th Edition Michael Starks Reality Press Las Vegas, Nevada Copyright © 2019 by Michael Starks All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted without the express consent of the author. Printed and bound in the United States of America. 4th Edition 2019 ISBN-13: 9781796542127 “At what point is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us it must spring up amongst us; it cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.” Abraham Lincoln (1838) “I do not say that democracy has been more pernicious on the whole, and in the long run, than monarchy or aristocracy. Democracy has never been and never can be so durable as aristocracy or monarchy; but while it lasts, it is more bloody than either. … Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to say that democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious, or less avaricious than aristocracy or monarchy. It is not true, in fact, and nowhere appears in history. Those passions are the same in all men, under all forms of simple government, and when unchecked, produce the same effects of fraud, violence, and cruelty. -

Human Nature’, Science and International Political Theory

Chris Brown ‘Human nature’, science and international political theory Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Brown, Chris (2013) 'Human nature', science and international political theory. Journal of International Relations and Development, 16 (4). pp. 435-454. ISSN 1408-6980 DOI: 10.1057/jird.2013.17 © 2013 Macmillan Publishers Ltd This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/53575/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2014 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. ‘Human Nature’, Science and International Political Theory1 Enough is known, enough has been written, about what divides people: my purpose is to investigate what they have in common. (Zeldin, 1999: 16) Introduction: A Contradiction Outlined. Humanitarianism, human rights, humanity, human nature – there’s a family resemblance between these notions that is difficult to miss, and yet the discourse of international political theory does its best to do so, and the result is a pattern of thought and action that contains strange contradictions. -

Suicidal Utopian Delusions in the 21St Century

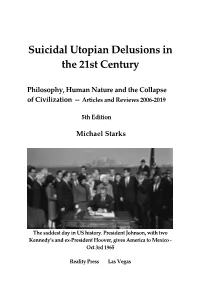

Suicidal Utopian Delusions in the 21st Century Philosophy, Human Nature and the Collapse of Civilization -- Articles and Reviews 2006-2019 5th Edition Michael Starks The saddest day in US history. President Johnson, with two Kennedy’s and ex-President Hoover, gives America to Mexico - Oct 3rd 1965 Reality Press Las Vegas Copyright © 2019 by Michael Starks All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted without the express consent of the author. Printed and bound in the United States of America. 5th Edition 2019 ISBN 9781080663781 “At what point is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us it must spring up amongst us; it cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.” Abraham Lincoln "Philosophers constantly see the method of science before their eyes and are irresistibly tempted to ask and answer questions in the way science does. This tendency is the real source of metaphysics and leads the philosopher into complete darkness." Ludwig Wittgenstein “He who understands baboon would do more towards metaphysics than Locke” Charles Darwin TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .............................................................................. I THE DESCRIPTION OF BEHAVIOR WITHOUT DELUSION 1. The Logical Structure of Consciousness (behavior, personality, rationality, higher order thought, intentionality) ............. 2 2. Review of Making the Social World by John Searle (2010)---10 3. Review of ‘Philosophy in a New Century’ by John Searle (2008)--33 4. Review of Wittgenstein's Metaphilosophy by Paul Horwich 248p (2013)--54 5. -

The 50 Most Influential Psychologists in the World 1

Taken from : https://thebestschools.org/features/most-influential-psychologists-world/ The Taos Institute’s co-founder and board president, Kenneth J. Gergen, PhD is featured in this article. (#19 on page 30 in alpha oder) ⁂ The 50 Most Influential Psychologists in the World 1. John R. Anderson | Cognitive Psychology Anderson was born in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, in 1947. He received his bachelor’s degree from the University of British Columbia in 1968, and his PhD in psychology from Stanford University in 1972. Today, he is Professor of Psychology (with a joint appointment in Computer Science) at Carnegie Mellon University. Anderson is a pioneer in the use of computers to model the “architecture” of the human mind, an approach known as “rational analysis.” He is perhaps best known for his ACT-R (Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational) proposal regarding the hypothetical computational structures underlying human general intelligence. Anderson also engaged in careful experimental studies, using fMRI technology, in an effort to provide empirical support for his theoretical models. Out this work came a number of insights now considered basic to cognitive science, such as, notably, the stage theory of problem-solving (encoding, planning, solving, and response stages), and the decomposition theory of learning (breaking down a problem into more-manageable components, also known as chunking). In his path-breaking early work, Anderson collaborated with Herbert Simon and other giants in the history of cognitive science. In more recent years, he has been involved in the development of intelligent tutoring systems. The author or co-author of over 320 peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters, and the author, co-author, or editor of six highly influential books, Anderson has received numerous awards, grants, fellowships, lectureships, and honorary degrees.