A Study of Postwar Architecture in Center City, Philadelphia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Program Book

PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 AWARDS ACHIEVEMENT PRESERVATION e join eas us pl in at br ing le e c 1996 2021 p y r e e e a c s rs n e a rv li ati o n al 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS WEDNESDAY, JUNE 9, 2021 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARD HONOREES Your knowledge, commitment, and advocacy create a better future for our city. And best wishes to the Preservation Alliance as you celebrate 25 years of invaluable service to the Greater Philadelphia region. pmcpropertygroup.com 1 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 WELCOME TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS HONORING THE INDIVIDUALS, ORGANIZATIONS, BUSINESSES, AND PROJECTS THROUGHOUT GREATER PHILADELPHIA THAT EXEMPLIFY OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Sponsors . 4 Executive Director’s Welcome . .. 6 Board of Directors . 8 Celebrating 25 Years: A Look Back . 9 Special Recognition Awards . 11 Advisory Committee. 11 James Biddle Award . 12 Board of Directors Award . 13 Rhoda and Permar Richards Award. 13 Economic Impact Award . 14 Preservation Education Awards . 14-15 John Andrew Gallery Community Action Awards . 15-16 Public Service Awards . 16-17 Young Friends of the Preservation Alliance Award . 17 AIA Philadelphia Henry J . Magaziner Award . .. 18 AIA Philadelphia Landmark Building Award . .. 18 Members of the Grand Jury . .. 19 Grand Jury Awards and Map . 20 In Memoriam . 46 Video by Mitlas Productions LLC | Graphic design by Peltz Creative Program editing by Fabien Communications 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PRESERVATION ALLIANCE FOR GREATER PHILADELPHIA 2 3 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 OUR SPONSORS ALABASTER PMC Property Group Brickstone IBEW Local Union 98 Post Brothers MARBLE A. -

Media Inquiries

2010 WORLD MONUMENTS FUND/KNOLL MODERNISM PRIZE AWARDED TO BIERMAN HENKET ARCHITECTEN AND WESSEL DE JONGE ARCHITECTEN Award given for restoration of Zonnestraal Sanatorium, in Hilversum, The Netherlands; rescue of iconic building helped launch global efforts to preserve modern architecture at risk. For Immediate Release—New York, NY, October 5, 2010. Bonnie Burnham, president, World Monuments Fund (WMF), announced today that WMF has awarded its 2010 World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize to Bierman Henket architecten and Wessel de Jonge architecten, leading practitioners in the restoration of modern buildings, for their technically and programmatically exemplary restoration of the Zonnestraal Sanatorium (designed 1926–28; completed 1931), in Hilversum, The Netherlands. The sanatorium is a little-known but iconic modernist building designed by Johannes Duiker (1890–1935) and Bernard Bijvoet (1889–1979). The biennial award will Zonnestraal, Main Pavilion, 2004 (post-restoration). Photo courtesy Bierman Henket architecten and Wessel de Jonge architecten. be presented to the Netherlands- based firms at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), on November 18, 2010, by Ms. Burnham; Barry Bergdoll, MoMA’s Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture & Design and chairman of the Prize jury; and Andrew Cogan, CEO, Knoll, Inc. The presentation will be followed by a free public lecture by Messrs. Henket and de Jonge, who will accept the award on behalf of their firms. The World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize is the only prize to acknowledge the specific and growing threats facing significant modern buildings, and to recognize the architects and designers who help ensure their rejuvenation and long-term survival through new design solutions. -

Finding Aid for the Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The

George Howe, P.S.F.S. Building, ca. 1926 THE ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MELLOR, MEIGS & HOWE COLLECTION (Collection 117) A Finding Aid for The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania © 2003 The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection Finding Aid Archival Description Descriptive Summary Title: Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection, 1915-1975, bulk 1915-1939. Coll. ID: 117 Origin: Mellor, Meigs & Howe, Architects, and successor, predecessor and related firms. Extent: Architectural drawings: 1004 sheets; Photographs: 83 photoprints; Boxed files: 1/2 cubic foot. Repository: The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania 102 Meyerson Hall Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6311 (215) 898-8323 Abstract: The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection comprises architectural records related to the practices of Mellor, Meigs & Howe and its predecessor and successor firms. The bulk of the collection documents architectural projects of the following firms: Mellor, Meigs & Howe; Mellor & Meigs; Howe and Lescaze; and George Howe, Architect. It also contains materials related to projects of the firms William Lescaze, Architect and Louis E. McAllister, Architect. The collection also contains a small amount of personal material related to Walter Mellor and George Howe. Indexes: This collection is included in the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings Project, a searchable database of architectural research materials related to architects and architecture in Philadelphia and surrounding regions: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org Cataloging: Collection-level records for materials in the Architectural Archives may be found in RLIN Eureka, the union catalogue of members of the Research Libraries Group. -

Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description

MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION FUND APPLICATION Center City District: Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description The Center City District (CCD), a private-sector sponsored business improvement district, authorized under the Commonwealth’s Municipality Authorities Act, seeks to improve the open area and entrances to public transit between the two original Penn Center buildings, bounded by Market Street and JFK Boulevard and 15th and 16th Streets. In 2014, the CCD completed the transformation of Dilworth Park into a first class gateway to transit and a welcoming, sustainably designed civic commons in the heart of Philadelphia. In 2018, the City of Philadelphia completed the renovations of LOVE Park, between 15th and 16th Street, JFK Boulevard and Arch Street. The adjacent Penn Center open space should be a vibrant pedestrian link between the office district and City Hall, a prominent gateway to transit and an attractive setting for businesses seeking to capitalize on direct connections to the regional rail and subway system. However, it is neither well designed nor well managed. While it is perceived and used as public space, its divided ownership between the two adjacent Penn Center buildings and SEPTA has long hampered efforts for a coordinated improvement plan. The property lines runs east/west through the middle of the plaza with Two Penn Center owning the northern half, 1515 Market owning the southern half and neither party willing to make improvements without their neighbor making similar improvements. Since it opened in the early 1960s, Penn Center plaza has never lived up to its full potential. The site was created during urban renewal with the demolition of the above ground, Broad Street Station and the elevated train tracks that ran west to 30th Street. -

Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Tour Format

Tour Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Accessibility Format ET101 Historic Boathouse Row 05/18/16 8:00 a.m. 2.00 LUs/GBCI Take an illuminating journey along Boathouse Row, a National Historic District, and tour the exteriors of 15 buildings dating from Bus and No 1861 to 1998. Get a firsthand view of a genuine labor of Preservation love. Plus, get an interior look at the University Barge Club Walking and the Undine Barge Club. Tour ET102 Good Practice: Research, Academic, and Clinical 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 1.50 LUs/HSW/GBCI Find out how the innovative design of the 10-story Smilow Center for Translational Research drives collaboration and accelerates Bus and Yes SPaces Work Together advanced disease discoveries and treatment. Physically integrated within the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Walking Advanced Medicine and Jordan Center for Medical Education, it's built to train the next generation of Physician-scientists. Tour ET103 Longwood Gardens’ Fountain Revitalization, 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 3.00 LUs/HSW/GBCI Take an exclusive tour of three significant historic restoration and exPansion Projects with the renowned architects and Bus and No Meadow ExPansion, and East Conservatory designers resPonsible for them. Find out how each Professional incorPorated modern systems and technologies while Walking Plaza maintaining design excellence, social integrity, sustainability, land stewardshiP and Preservation, and, of course, old-world Tour charm. Please wear closed-toe shoes and long Pants. ET104 Sustainability Initiatives and Green Building at 05/18/16 10:30 a.m. -

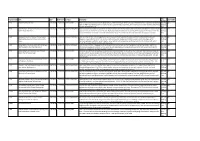

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill -

MODERN ARCHITECTURE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION I, Momaexh 0015 Masterchecklist

BaM-- fu-- ~~{S~ MODERN ARCHITECTURE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION I, MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist NEW YORK FEB. 10 TO MARCH 23,1932 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PHOTOGRAPHS IN THE EXHIBITION ILLUSTRATING THE EXTENT OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE AUSTRIA LOIS WELZENBACHER:Apartment House, Innsbruck. 1930. BELGIUM H. L. DEKONINCK:Lenglet House, Uccle, near Brussels. 1926. MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist CZECHOSLOVAKIA I OTTO EISLER:House for Two Brothers, Brno, 1931. BOHUSLAVFucns: Students' Clubhouse, Brno. 1931. I I LUDVIKKYSELA:Bata Store, Prague. 1929. ENGLAND AMYAS CONNELL:House in Amersham, Buckinghamshire. 193I. JOSEPHEMBERTON:Royal Corinthian Yacht Club, Burnham-an-Crouch. 1931. FINLAND o ALVAR AALTO: Turun Sanomat Building, Abo. 1930. FRANCE Gabriel Guevrekian: Villa Heim, Neuilly-sur-Seine. 1928. ANDRE LURyAT:Froriep de Salis House, Boulogne-sur-Seine. 1927. ANDRE LURCAT:Hotel Nord-Sud, Calvi, Corsica. 1931. 2!j ,I I I I I I FRANCE (continued) ROBMALLET-STEVENS:de Noailles Villa, Hyeres. "925. PAULNELSON: Pharmacy, Paris. 1931. GERMANY OTTOHAESLER: Old People's Home, Kassel. 1931. LUCKHARDT&' ANKER: Row of Houses, Berlin. "929. ERNSTMAY &' ASSOCIATES:Friedrich Ebert School, Frankfort-on-Main. 1931. 28 0 MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist ERICHMENDELSOHN:Schocken Department Store, Chemnitz. "9 -3 . ERICHMENDELSOHN:House of the Architect, Berlin. "930. HANSSCHAROUN: "Wohnheim;" Breslau. 1930. KARLSCHNEIDER:Kunstverein, Hamburg. "930. HOLLAND BRINKMAN&' VAN DERVLUGT: Van Nelle Factory, Rotterdam. 1928-30. I I W, J. DUIKER: Open Air School, Amsterdam. "931. G. RIETVELD:House at Utrecht. "924. ITALY 1. FIGINI &' G. POLLIN!:Electrical House at the Monza Exposition. "930. I' JAPAN ISABUROUENO: Star Bar, Kioto. "931. MAMORU YAMADA: Electrical Laboratory, Tokio. "930. SPAIN LABAYEN&' AIZPUR1JA:Club House, San Sebastian. "930. 26 SWEDEN SVEN MARKELlus &' UNO AHREN: Students' Clubhouse, Stockholm. -

Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Catherine S

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1-1-2005 Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Catherine S. Jefferson University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Jefferson, Catherine S., "Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia" (2005). Theses (Historic Preservation). 30. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2005. Advisor: David Hollenberg This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2005. Advisor: David Hollenberg This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 ADAPTIVE REUSE: RECENT HOTEL CONVERSIONS IN DOWNTOWN PHILADELPHIA Catherine Sarah Jefferson A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2005 _____________________________ _____________________________ Advisor Reader David Hollenberg John Milner Lecturer in Historic Preservation Adjunct Professor of Architecture _____________________________ Program Chair Frank G. Matero Associate Professor of Architecture ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and support of a number of people. -

Paimio Sanatorium

MARIANNA HE IKINHEIMO ALVAR AALTO’S PAIMIO SANATORIUM PAIMIO AALTO’S ALVAR ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: : PAIMIO SANATORIUM ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium TIIVISTELMÄ rkkitehti, kuvataiteen maisteri Marianna Heikinheimon arkkitehtuurin histo- rian alaan kuuluva väitöskirja Architecture and Technology: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio A Sanatorium tarkastelee arkkitehtuurin ja teknologian suhdetta suomalaisen mestariarkkitehdin Alvar Aallon suunnittelemassa Paimion parantolassa (1928–1933). Teosta pidetään Aallon uran käännekohtana ja yhtenä maailmansotien välisen moder- nismin kansainvälisesti keskeisimpänä teoksena. Eurooppalainen arkkitehtuuri koki tuolloin valtavan ideologisen muutoksen pyrkiessään vastaamaan yhä nopeammin teollis- tuvan ja kaupungistuvan yhteiskunnan haasteisiin. Aalto tuli kosketuksiin avantgardisti- arkkitehtien kanssa Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne -järjestön piirissä vuodesta 1929 alkaen. Hän pyrki Paimion parantolassa, siihenastisen uransa haastavim- massa työssä, soveltamaan uutta näkemystään arkkitehtuurista. Työn teoreettisena näkökulmana on ranskalaisen sosiologin Bruno Latourin (1947–) aktiivisesti kehittämä toimijaverkkoteoria, joka korostaa paitsi sosiaalisten, myös materi- aalisten tekijöiden osuutta teknologisten järjestelmien muotoutumisessa. Teorian mukaan sosiaalisten ja materiaalisten toimijoiden välinen suhde ei ole yksisuuntainen, mikä huo- mio avaa kiinnostavia näkökulmia arkkitehtuuritutkimuksen kannalta. Olen ymmärtänyt arkkitehtuurin -

Theodore Roosevelt Middle School), in Assessor's Parcel Block No. 1061, Lot No

FILE NO. 180003 ORDINANCE NO. 37-19 1 [Planning Code - Landmark Designation - 460 Arguello Boulevard (aka Theodore Roosevelt Middle School)] 2 3 Ordinance amending the Planning Code to designate 460 Arguello Boulevard (aka 4 Theodore Roosevelt Middle School), in Assessor's Parcel Block No. 1061, Lot No. 049, 5 as a Landmark under Article 10 of the Planning Code; affirming the Planning 6 Department's determination under the California Environmental Quality Act; and 7 making public necessity, convenience, and welfare findings under Planning Code, 8 Section 302, and findings of consistency with the General Plan, and the eight priority 9 policies of Planning Code, Section 101.1. 10 NOTE: Unchanged Code text and uncodified text are in plain Ariai font. Additions to Codes are in single-underline italics Times New Roman font. 11 Deletions to Codes are in strikf!through italics Times New Roman font. Board amendment additions are in double-underlined Arial font. 12 Board amendment deletions are in strikethrough Arial font. Asterisks (* * * *) indicate the omission of unchanged Code 13 subsections or parts of tables. 14 15 Be it ordained by the People of the City and County of San Francisco: 16 Section 1. Findings. 17 (a) CEQA and Land Use Findings. 18 (1) The Planning Department has determined that the proposed Planning Code 19 amendment is subject to a Categorical Exemption from the California Environmental Quality 20 Act (California Public Resources Code section 21000 et seq., "CEQA") pursuant to Section 21 15308 of the Guidelines for implementation of the statute for actions by regulatory agencies 22 for protection of the environment (in this case, landmark designation). -

Lecture Handouts, 2013

Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Classs #1 INTRODUCTION & OVERVIEW Introductions Expectations Textbooks Assignments Electronic reserves Research Project Sources History-Theory-Criticism Methods & questions of Architectural History Assignments: Initial Paper Topic form Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Classs #2 ARCHITECTURE OF WWII The World at War (1939-45) Nazi War Machine - Rearming Germany after WWI Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect & responsible for Nazi armaments Autobahn & Volkswagen Air-raid Bunkers, the “Atlantic Wall”, “Sigfried Line”, by Fritz Todt, 1941ff Concentration Camps, Labor Camps, POW Camps Luftwaffe Industrial Research London Blitz, 1940-41 by Germany Bombing of Japan, 1944-45 by US Bombing of Germany, 1941-45 by Allies Europe after WWII: Reconstruction, Memory, the “Blank Slate” The American Scene: Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941 Pentagon, by Berman, DC, 1941-43 “German Village,” Utah, planned by US Army & Erich Mendelsohn Military production in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Akron, Cleveland, Gary, KC, etc. Albert Kahn, Detroit, “Producer of Production Lines” * Willow Run B-24 Bomber Plant (Ford; then Kaiser Autos, now GM), Ypsilanti, MI, 1941 Oak Ridge, TN, K-25 uranium enrichment factory; town by S.O.M., 1943 Midwest City, OK, near Midwest Airfield, laid out by Seward Mott, Fed. Housing Authortiy, 1942ff Wartime Housing by Vernon Demars, Louis Kahn, Oscar Stonorov, William Wurster, Richard Neutra, Walter Gropius, Skidmore-Owings-Merrill, et al * Aluminum Terrace, Gropius, Natrona Heights, PA, 1941 Women’s role in the war production, “Rosie the Riverter” War time production transitions to peacetime: new materials, new design, new products Plywod Splint, Charles Eames, 1941 / Saran Wrap / Fiberglass, etc. -

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Oral History Transcript

The Cultural Landscape Foundation® Pioneers of American Landscape Design® ___________________________________ CORNELIA HAHN OBERLANDER ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ___________________________________ Interview conducted August 3-5, 2008 Charles A. Birnbaum, FASLA, FAAR Tom Fox, FASLA, videographer The Cultural Landscape Foundation® Pioneers of American Landscape Design® Oral History Series: Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Interview Transcript Table of Contents Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Interview Transcript ............................................................. 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 4 Childhood and Education ............................................................................................... 5 Memories of Family Life in Europe .................................................................................... 5 Coming to America ............................................................................................................ 6 Smith College ..................................................................................................................... 7 Smith Professors Made a Difference ................................................................................. 8 Lessons from Harvard ........................................................................................................ 9 Meeting Larry Halprin .....................................................................................................