The Whistler's Story Tragedy and the Enlightenment Imagination in the Eh Art of Midlothian Alan Riach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of the Old Parish Registers of Scotland 758-811

List of the Old Parish Registers Midlothian (Edinburgh) OPR MIDLOTHIAN (EDINBURGH) 674. BORTHWICK 674/1 B 1706-58 M 1700-49 D - 674/2 B 1759-1819 M 1758-1819 D 1784-1820 674/3 B 1819-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-54 675. CARRINGTON (or Primrose) 675/1 B 1653-1819 M - D - 675/2 B - M 1653-1819 D 1698-1815 675/3 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1793-1854 676. COCKPEN* 676/1 B 1690-1783 M - D - 676/2 B 1783-1819 M 1747-1819 D 1747-1813 676/3 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1832-54 RNE * See Appendix 1 under reference CH2/452 677. COLINTON (or Hailes) 677/1 B 1645-1738 M - D - 677/2 B 1738-1819* M - D - 677/3 B - M 1654-1819 D 1716-1819 677/4 B 1815-25* M 1815-25 D 1815-25 677/5 B 1820-54*‡ M 1820-54 D - 677/6 B - M - D 1819-54† RNE 677/7 * Separate index to B 1738-1851 677/8 † Separate index to D 1826-54 ‡ Contains index to B 1852-54 Surname followed by forename of child 678. CORSTORPHINE 678/1 B 1634-1718 M 1665-1718 D - 678/2 B 1709-1819 M - D - 678/3 B - M 1709-1819 D 1710-1819 678/4 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-54 List of the Old Parish Registers Midlothian (Edinburgh) OPR 679. CRAMOND 679/1 B 1651-1719 M - D - 679/2 B 1719-71 M - D - 679/3 B 1771-1819 M - D - 679/4 B - M 1651-1819 D 1816-19 679/5 B 1819-54 M 1819-54 D 1819-54* * See library reference MT011.001 for index to D 1819-54 680. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Welcome to Midlothian (PDF)

WELCOME TO MIDLOTHIAN A guide for new arrivals to Midlothian • Transport • Housing • Working • Education and Childcare • Staying safe • Adult learning • Leisure facilities • Visitor attractions in the Midlothian area Community Learning Midlothian and Development VISITOr attrACTIONS Midlothian Midlothian is a small local authority area adjoining Edinburgh’s southern boundary, and bordered by the Pentland Hills to the west and the Moorfoot Hills of the Scottish Borders to the south. Most of Midlothian’s population, of just over 80,000, lives in or around the main towns of Dalkeith, Penicuik, Bonnyrigg, Loanhead, Newtongrange and Gorebridge. The southern half of the authority is predominantly rural, with a small population spread between a number of villages and farm settlements. We are proud to welcome you to Scotland and the area www.visitmidlothian.org.uk/ of Midlothian This guide is a basic guide to services and • You are required by law to pick up litter information for new arrivals from overseas. and dog poo We hope it will enable you to become a part of • Smoking is banned in public places our community, where people feel safe to live, • People always queue to get on buses work and raise a family. and trains, and in the bank and post You will be able to find lots of useful information on office. where to stay, finding a job, taking up sport, visiting tourist attractions, as well as how to open a bank • Drivers thank each other for being account or find a child-minder for your children. considerate to each other by a quick hand wave • You can safely drink tap water There are useful emergency numbers and references to relevant websites, as well as explanations in relation to your rights to work. -

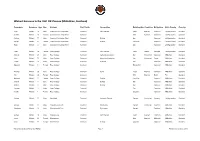

1851 Census (Midlothian).Xlsx

Wishart Surname in the 1851 UK Census (Midlothian, Scotland) Forename Surname Age Sex Address Civil Parish Occupation Relationship Condition Birthplace Birth County Country Hugh Wishart 33 Male Cramond Park Lodge West Cramond Farm Servant Head Married Cramond Linlithgowshire Scotland Isabella Wishart 32 Female Cramond Park Lodge West Cramond Wife Married Cramond Linlithgowshire Scotland Andrew Wishart 11 Male Cramond Park Lodge West Cramond Scholar Son Cramond Linlithgowshire Scotland Cecilia Wishart 6 Female Cramond Park Lodge West Cramond Scholar Daughter Cramond Linlithgowshire Scotland Hugh Wishart 4 Male Cramond Park Lodge West Cramond Son Cramond Linlithgowshire Scotland Janet Wishart 50 Female Rose Cottage Cramond Farm Servant Head Widow Bathgate Linlithgowshire Scotland Andrew Wishart 21 Male Rose Cottage Cramond Agricultural Labourer Son Unmarried Cramond Midlothian Scotland John Wishart 19 Male Rose Cottage Cramond Agricultural Labourer Son Unmarried Currie Midlothian Scotland James Wishart 13 Male Rose Cottage Cramond At Home Son Cramond Midlothian Scotland Margaret Wishart 3 Female Rose Cottage Cramond Grandchild Cramond Midlothian Scotland Thomas Wishart 36 Male Rose Cottage Cramond Carter Head Married Cramond Midlothian Scotland Ann Wishart 36 Female Rose Cottage Cramond Wife Married Beath Fife Scotland Margaret Wishart 11 Female Rose Cottage Cramond Scholar Daughter Cramond Midlothian Scotland Andrew Wishart 9 Male Rose Cottage Cramond Scholar Son Cramond Midlothian Scotland William Wishart 6 Male Rose Cottage Cramond Scholar -

Enlightened Scotland: How the Age of Reason Made an Impact on the Country's Thinkers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten Riach, A. (2017) Enlightened Scotland: How the Age of Reason made an impact on the country's thinkers. National, 2017, 21 Apr. This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/161602/ Deposited on: 01 May 2018 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk The Enlightenment Alan Riach From the moment in 1660 when Thomas Urquhart dies laughing to the publication of Walter Scott’s first novel Waverley in 1814, Scottish literature becomes increasingly aware of itself. That is, Scottish writers – some of them – become increasingly self-conscious of their own literary ancestors. This is brought about centrally in the work of Allan Ramsay (1684-1758), in his anthologies of earlier poets, and in the edition of Gavin Douglas’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid (1710) published by Thomas Ruddiman (1674-1757), which was probably what Burns was quoting from in the epigraph to “Tam o’ Shanter”: “Of Brownyis and Bogillis full is this Buke.” The evolutionary turn towards greater self-awareness, the process of questioning the formation of national identity, the position of that identity in an ongoing struggle for economic prosperity and international colonial and imperial power, is central in the history of Scotland from around 1660 to 1707. It underlies and suffuses the writing of philosophers, politicians, dramatists, novelists, poets, and travel writers. -

Minutes of Bonaly Primary School Parent Council Meeting Held on Tuesday 18 November 2014 at 7.00Pm in the School (Meeting Room)

Minutes of Bonaly Primary School Parent Council meeting held on Tuesday 18 November 2014 at 7.00pm in the School (meeting room) Present: Lindsay Blakemore Chair Catherine Diamond Year Group Representative P1 Stephanie Nichol Year Group Representative P2 Avril Beveridge Year Group Representative P4 Susan Hodgson Year Group Representative P5 Roberta Fiddes Year Group Representative P6 Dawn Alsop Year Group Representative P7 Fiona Gemmell Vice-Treasurer Heidi Horsburgh Clubs Co-ordinator (to 18.11.14) Nichola Pearce Fundraising and Events Committee Chair Linda Macdonald Teacher Representative Tim Lawson Colinton Amenities Association Representative Councillor Jason Rust Local Council Representative In attendance: Aileen Kirchin Interim Clubs Co-ordinator (from 18.11.14) Peter Gorrie new Acting Headteacher (from 01.12.14) Laurinda Ramage Headteacher Ailsa Taylor Clerk to the Parent Council Sarah Beevers Parent (item 2 only) Tracy Mcgillivray Parent (item 2 only) Penny Browning Parent (item 2 only) 1. Apologies for Absence Apologies for absence had been received from: Melanie Clark - Nursery Year Group Representative Dave Richards - Year Group Representative P3 Jenny Brons - Treasurer 2. Charity Fun Run Funding The Bonaly Children's Fun Run organisers Sarah Beevers, Penny Browning and Tracy Mcgillivray were welcomed to the meeting. The Parent Council had considered a request at their meeting in May 2014 for reimbursement for medals that were to be provided to children at the end of their run (at the cost of £220 for 172 medals). This had been discussed at length, and resulted in the agreement that if the Parent Council covered this request, then funds would effectively be used to make a charitable donation. -

Newbattle Accessibility Report August 2013

Newbattle Accessibility Report August 2013 Newbattle Accessibility Report CONTROL SHEET CLIENT: Persimmon Homes PROJECT TITLE: Newbattle REPORT TITLE: Accessibility Report PROJECT REFERENCE: 99999/ED/TR/01 Issue and Approval Schedule: ISSUE 1 Name Signature Date Issue Prepared by Suzanne Bullimore 15/08/13 Reviewed by Calum Robertson 28/08/13 Approved by Donald Stirling 29/08/13 Revision Record: Issue Date Status Description By Chk App 2 3 This report has been prepared in accordance with procedure OP/P02 of the Fairhurst Quality Management System. Newbattle Accessibility Report Contents 1 Introduction _______________________________________________________________ 1 1.1 Introduction 1 2 Accessibility _______________________________________________________________ 2 2.1 Introduction and Surrounding Land Use 2 2.2 Pedestrian Provision 3 2.3 Cycling 6 2.4 Public Transport 7 2.5 Rail 9 2.6 Access by Private Car 9 2.7 Vehicular Access to development sites 9 3 Development Trips_________________________________________________________ 10 3.1 Trip Generation 10 4 Summary and Conclusion___________________________________________________ 12 4.1 Summary 12 4.2 Conclusions 12 Newbattle Accessibility Report 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.1.1 This report has been prepared on behalf of Persimmon Homes in support of proposals for residential development of up to 180 dwellings at Newbattle Home Farm, Newtongrange, Midlothian. 1.1.2 The site includes 26 acres of agricultural land on the northern edge of Newtongrange adjacent to the settlement boundary and existing residential areas. The Midlothian Local Plan was adopted in 2008 and confirms that the site is located in countryside within a conservation area (but outwith the green belt) comprising agricultural land. Most of the site is located outwith land currently designated as a Nationally Important Garden and Designated Landscape. -

Circulation, Monuments, and the Politics of Transmission in Sir Walter Scott’S Tales of My Landlord by Kyoko Takanashi

CirCUlaTion, MonUMenTs, and THe PoliTiCs of TransMission in sir WalTer sCoTT’s TaLEs of My LandLord by kyoko TakanasHi i n the opening passage of sir Walter scott’s The Heart of Midlothian, the narrator, Peter Pattieson, asserts that the “times have changed in nothing more . than in the rapid conveyance of intelligence and communication betwixt one part of scotland and another.”1 Here, Pattieson seems to confirm the crucial role that the speed of print distribution played in romantic print culture, particularly in relation to time-sensitive reading material such as periodical publications, po- litical pamphlets, and statements by various corresponding societies.2 indeed, the rapidity of the mail-coach that enabled up-to-date com- munication seems crucial to our understanding of the romantic period as an age that became particularly cognizant of history as an ongoing process, forming, as it were, what benedict anderson characterizes as a “historically clocked, imagined community.”3 and yet the first half of Pattieson’s sentence reveals ambivalence about such change; while he admits that there has been dramatic increase in the speed of com- munication, he also asserts that “nothing more” has changed. despite the presence of “the new coach, lately established on our road,” Pat- tieson considers the village of Gandercleugh as otherwise unchanged, since it still offers him the opportunity to collect local, historical tales that will eventually be published as Tales of My Landlord (H, 14). This representation of communication infrastructures in Tales of My Landlord series does not so much confirm the thorough penetration of a national print-based imagined community as it exposes how this national infrastructure existed uneasily alongside pockets of traditional, local communities. -

Novels of Walter Scott As a Mimetic Vehicle for Portraying Historical Characters

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 69-74 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. NOVELS OF WALTER SCOTT AS A MIMETIC VEHICLE FOR PORTRAYING HISTORICAL CHARACTERS SHEEBA AZHAR 1 & SYED ABID ALI 2 1Assistant Professor, Department of English, College of Applied Medical Science, Hafr Al Batin University of Dammam,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 2Lecturer, Department of English, College of Applied Medical Science, Hafr Al Batin University of Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia ABSTRACT Sir Walter Scott is a great historical novelist. Scott’s knowledge of human psychology is evident to from the presentation of his characters. Scott’s assertion in the first chapter of Waverley is that “the object of my tale is more a description of men than manners.” He has thrown the force of his narrative upon the characters and passions of the actors; those passions, that are common to men in all stages of society, and which have alike agitated the human heart in all ages. His characters present their inherent traits with an unequalled eloquence. They are not made up of one or two sets of qualities. They are moulded from the substance of which human life is made and possess all its attributes. Present paper examines Sir Walter Scott’s method of characterization and point of excellence in the portrayal of various historical characters. KEYWORDS: Sir Walter Scott, Unequalled Eloquence, Waverley INTRODUCTION According to George Lukacs “what matters in the historical novel is not the re-telling of great historical events, but the poetic awakening of the people who are figured in those events” 1 It means that the responsibilities of a historical novelist are doubled as compared to those of the general novelist, in the matter of characterization, for he has to introduce characters from the past. -

Walter Scott

READING Walter Scott Walter Scott was a famous Scottish novelist, poet, historian and biographer. He is often considered the greatest author of historical novels. Walter Scott was born on August 15, 1771, in Edinburgh, Scotland. His father was a lawyer and his mother was the daughter of a doctor. When he was young, he liked listening to stories about Scotland’s past. He also read a lot of books. He studied at the University of Edinburgh and prepared for a career in law, but his real interest was literature. In the mid-1790s, Scott became interested in German Romanticism. He translated some books from German, for example Goethe’s play Götz von Berlichingen. In 1802–1803, he published Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, a collection of Scottish ballads. He went on to write his own poetry and published a series of long poems, starting with The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805). All of these poems were best-sellers and made Scott famous. The most successful of these poems was The Lady of the Lake, published in 1810. Scott led a highly active literary and social life during these years. He also became a partner in a printing and publishing firm. The company had some financial problems and almost went bankrupt in 1813. Scott saved it, but from that time on everything he wrote was done partly to make money. In 1814, Walter Scott published a novel called Waverley. It is a historical novel about a rebellion which took place in Scotland in 1745. The book was extremely successful. Scott published it anonymously. -

The Author of Waverley, with His Various Personas, Is a Highly

Promoting Saint Ronans Well: Scotts Fiction and Scottish Community in Transition MATSUI Yuko The Author of Waverley, with his various personas, is a highly sociable and com- municative writer, as we observe in the frequent and lively exchanges between the author and his reader or characters in the conclusions of Old Mortality1816 and Redgauntlet1824 , or in the prefaces to The Abbot1820 and The Betrothed1825 , to give only a few examples. Walter Scott himself, after giving up his anonymity, seems to enjoy an intimate author-reader relationship in his prefaces and notes to the Magnum Opus edition. Meanwhile, Scott often adapts and combines more than one historical event or actual person, his sources or originals, in his attempt to recre- ate the life of a particular historical period and give historical sense to it, as books like W. S. Crocketts The Scott Originals1912 eloquently testify, and with the Porteous Riot and Helen Walker in The Heart of Midlothian1818 as one of the most obvious examples. Both of these characteristics often tend to encourage an active interaction between the real and the imagined, or their confluence, within and outwith Scott's historical fiction, perhaps most clearly shown in the development of tourism in 19th century Scotland1. In the case of Saint Ronan’s Well1824 [1823], Scotts only novel set in the 19th century, its contemporaneity seems to have allowed that kind of interaction and confluence to take its own vigorous form, sometimes involving an actual commu- nity or other authors of contemporary Scotland. Thus, we would like to examine here the ways in which Scott adapts his sources to explore his usual interest in historical change in this contemporary fiction and how it was received, particularly in terms of its effect on a local community in Scotland and in terms of its inspiration for his fellow authors, and thus reconsider the part played by Scotts fiction in imagining and pro- moting Scotland in several ways, in present and past Scotland. -

Sir Walter Scott – Bringing out the Best in Us

Riach, A. (2017) Sir Walter Scott – Bringing out the best in us... National, 2017, 27 Jan. This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/161549/ Deposited on: 30 April 2018 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Approaching Walter Scott: Part Three Alan Riach In the final part of this series, Alan Riach looks at Scott’s late work and legacy: powerful in the 19th century but greatly diminished in the 20th century. Why? And, since the brilliant new Edinburgh edition of his works (Go to: http://www.walterscott.lib.ed.ac.uk/index.html) has made thorough revaluation possible, what would be good reason to read him in Scotland’s circumstances now? In the late 1820s, Scott’s health declined and in 1831, after a stroke, he travelled to Italy to try to recuperate, returning, still very ill, in 1832. As his carriage approached home, he seemed to be unconscious, but when the Eildon Hills appeared, he roused himself and according to his first biographer, John Gibson Lockhart, Scott became “greatly excited” and when he saw Abbotsford, “sprang up with a cry of delight.” Lockhart was determined to present an idealised picture of the last days of Scott, to give the impression that his characteristic decency was rewarded with a tranquil passing. Doubts have been raised about this, but Lockhart’s account is undeniably touching: “About half-past one p.m.