Chapter Five Spanish Co-Productions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Los Lunes Al Sol

CULTURA , LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTAC I ÓN / CULTURE , LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ I SSN 1697-7750 · VOL . XV I \ 2016, pp. 21-36 REV I STA D E ESTU di OS CULTURALES D E LA UN I VERS I TAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I D O I : HTTP ://D X .D O I .ORG /10.6035/CLR .2016.16.2 Los lunes al sol. Retrato social de historias de vida silenciadas Mondays in the Sun. A social Portrait of Silenced Lives’ Stories DIANA AMBER * JESÚS DOMINGO ** *UNIVERSIDAD DE JAÉN . **UNIVERSIDAD DE GRANADA Artículo recibido el / Article received: 01-09-2015 Artículo aceptado el / Article accepted: 10-08-2016 RESUMEN : La película Los lunes al sol ha tenido un fuerte impacto emocional y social en el colectivo de mayores de 45 años en desempleo. Numerosas iniciativas de acceso al empleo para los mayores la usan como referente reivindicativo. El estudio busca la comprensión de la imagen que el film ofrece sobre los desem- pleados mayores, con objeto de analizar las actitudes y experiencias de los per- sonajes frente al desempleo y del propio imaginario social sobre esta temática. La metodología utilizada es el análisis fílmico desde una vertiente discursiva y analítico-reflexiva, centrada principalmente en el análisis del hecho discursivo del film. Los resultados se centran en los entresijos personales, sociales y labo- rales de sus personajes. Describen e interpretan las escenas y escenarios más re- presentativos que componen y estructuran las historias narradas. Las principales conclusiones apuntan hacia la virtud del film para visibilizar la problemática y dignificar al colectivo desde la autocrítica social de esta realidad. -

Click to Download

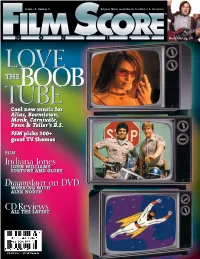

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

Spanish Language Films in the Sfcc Library

SPANISH LANGUAGE FILMS IN THE SFCC LIBRARY To help you select a movie that you will enjoy, it is recommended that you look at the description of films in the following pages. You may scroll down or press CTRL + click on any of the titles below to take you directly to the description of the movie. For more information (including some trailers), click through the link to the Internet Movie Database (www.imdb.com). All films are in general circulation and in DVD format unless otherwise noted. PLEASE NOTE: Many of these films contain nudity, sex, violence, or vulgarity. Just because a film has not been rated by the MMPA, does not mean it does not contain these elements. If you are looking for a film without those elements, consider viewing one of the films on the list on the last page of the document. A Better Life (2011) Age of Beauty / Belle epoque (1992) DVD/VHS All About My Mother / Todo sobre mi madre (1999) Alone / Solas (1999) And Your Mama Too / Y tu mamá también (2001) Aura, The / El aura (2005) Bad Education / La mala educación (2004) Before Night Falls / Antes que anochezca (2000) DVD/VHS Biutiful (2010) Bolivar I Am / Bolívar soy yo (2002) Broken Embraces / Abrazos rotos (2009) Broken Silence / Silencio roto (2001) Burnt Money / Plata quemada (2000) Butterfly / La lengua de las mariposas (1999) Camila (1984) VHS media office Captain Pantoja and the Special Services / Pantaleón y las visitadoras (2000) Carancho (2010) Cautiva (2003) Cell 211 / Celda 211 (2011) Chinese Take-Out(2011) Chronicles / Crónicas (2004) City of No Limits -

A Film by Woody Allen Javier Bardem Patricia Clarkson Penélope Cruz

A film by Woody Allen Javier Bardem Patricia Clarkson Penélope Cruz Kevin Dunn Rebecca Hall Scarlett Johansson Chris Messina Official Selection – 2008 Cannes Film Festival Release Date: 26 December 2008 Running Time: 96 mins Rated: TBC For more information contact Jillian Heggie at Hopscotch Films on 02 8303 3800 or at [email protected] VICKY CRISTINA BARCELONA Starring (in alphabetical order) Juan Antonio JAVIER BARDEM Judy Nash PATRICIA CLARKSON Maria Elena PENÉLOPE CRUZ Mark Nash KEVIN DUNN Vicky REBECCA HALL Cristina SCARLETT JOHANSSON Doug CHRIS MESSINA Co-Starring (in alphabetical order) ZAK ORTH CARRIE PRESTON PABLO SCHREIBER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON GARETH WILEY STEPHEN TENENBAUM Co-Producers HELEN ROBIN Executive Producer JAUME ROURES Co-Executive Producers JACK ROLLINS CHARLES H. JOFFE JAVIER MÉNDEZ Director of Photography JAVIER AGUIRRESAROBE Production Designer ALAIN BAINÉE Editor ALISA LEPSELTER Costume Designer SONIA GRANDE Casting JULIET TAYLOR & PATRICIA DiCERTO Additional Spanish Casting PEP ARMENGOL & LUCI LENOX * * * 2 VICKY CRISTINA BARCELONA Synopsis Woody Allen’s breezy new romantic comedy is about two young American women and their amorous escapades in Barcelona, one of the most romantic cities in the world. Vicky (Rebecca Hall) and Cristina (Scarlett Johansson) are best friends, but have completely different attitudes towards love. Vicky is sensible and engaged to a respectable young man. Cristina is sexually and emotionally uninhibited, perpetually searching for a passion that will sweep her off her feet. When Judy (Patricia Clarkson) and Mark (Kevin Dunn), distant relatives of Vicky, offer to host them for a summer in Barcelona, the two of them eagerly accept: Vicky wants to spend her last months as a single woman doing research for her Masters, and Cristina is looking for a change of scenery to flee the psychic wreckage of her last breakup. -

HP308: Contemporary Spanish Cinema (2015/16)

09/25/21 HP308: Contemporary Spanish Cinema | University of Warwick HP308: Contemporary Spanish Cinema View Online (2015/16) [1] Acevedo-Muñoz, E.R. 2007. Pedro Almodóvar. BFI. [2] Allinson, M. 2001. A Spanish labyrinth: the films of Pedro Almodóvar. Tauris. [3] Almodóvar, P. et al. 2006. Pepi, Luci, Bom. Optimum Releasing. [4] Almodóvar, P. et al. 2006. Women on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Distributed by Optimum Releasing. [5] Almodóvar, P. and Maura, C. 2004. What have I done to deserve this? Optimum Releasing. [6] Amenábar, A. et al. 2007. Open your eyes: Abre los ojos. Lionsgate. [7] 1/13 09/25/21 HP308: Contemporary Spanish Cinema | University of Warwick Amenábar, A. et al. 2001. Tesis: [Thesis. Tartan Video. [8] Begin, P. 2009. Regarding the pain of others: The art of realism in Icar Bollan’s <I>Te doy mis ojos</I>. Studies in Hispanic Cinema. 6, 1 (Dec. 2009), 31–44. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1386/shci.6.1.31/1. [9] Berger, P. et al. 2013. Blancanieves. StudioCanal. [10] Besas, P. 1985. Behind the Spanish lens: Spanish cinema under fascism and democracy. Arden Press. [11] Buse, P. et al. 2012. The cinema of Álex de la Iglesia. Manchester University Press. [12] Buse, P. et al. 2012. The cinema of Álex de la Iglesia. Manchester University Press. [13] Cuerda, J.L. et al. 2000. Butterfly. Miramax Home Entertainment. [14] Davies, A. 2009. Woman and home: gender and the theorisation of Basque (national) cinema. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies. 10, 3 (Sep. 2009), 359–372. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/14636200903186913. -

Hliebing Dissertation Revised 05092012 3

Copyright by Hans-Martin Liebing 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Hans-Martin Liebing certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Transforming European Cinema : Transnational Filmmaking in the Era of Global Conglomerate Hollywood Committee: Thomas Schatz, Supervisor Hans-Bernhard Moeller Charles Ramírez Berg Joseph D. Straubhaar Howard Suber Transforming European Cinema : Transnational Filmmaking in the Era of Global Conglomerate Hollywood by Hans-Martin Liebing, M.A.; M.F.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication In loving memory of Christa Liebing-Cornely and Martha and Robert Cornely Acknowledgements I would like to thank my committee members Tom Schatz, Charles Ramírez Berg, Joe Straubhaar, Bernd Moeller and Howard Suber for their generous support and inspiring insights during the dissertation writing process. Tom encouraged me to pursue this project and has supported it every step of the way. I can not thank him enough for making this journey exciting and memorable. Howard’s classes on Film Structure and Strategic Thinking at The University of California, Los Angeles, have shaped my perception of the entertainment industry, and having him on my committee has been a great privilege. Charles’ extensive knowledge about narrative strategies and Joe’s unparalleled global media expertise were invaluable for the writing of this dissertation. Bernd served as my guiding light in the complex European cinema arena and helped me keep perspective. I consider myself very fortunate for having such an accomplished and supportive group of individuals on my doctoral committee. -

A Film by Woody Allen

Persmap - Ampèrestraat 10 - 1221 GJ Hilversum - T: 035-6463046 - F: 035-6463040 - email: [email protected] A film by Woody Allen Spanje · 2008 · 35mm · color · 96 min. · Dolby Digital · 1:1.85 Vicky en Cristina zijn twee hartsvriendinnen met tegengestelde karakters. Vicky is de verstandige en verloofd met een degelijke jongeman, Cristina daarentegen laat zich leiden door haar gevoelens en is voortdurend op zoek naar nieuwe passies en seksuele ervaringen. Wanneer ze de kans krijgen om de zomer in Barcelona door te brengen, zijn ze allebei dolenthousiast : Vicky wil nog voor haar huwelijk een master behalen, terwijl Cristina na haar laatste liefdesperikelen behoefte heeft aan iets nieuws. Op een avond ontmoeten ze in een kunstgalerij een Spaanse schilder. Juan Antonio is knap, sensueel en verleidelijk en doet hen een nogal ongewoon voorstel… Maar deze nieuwe vriendschap valt niet in de smaak van Juan Antonio’s ex-vriendin. www.vickycristina-movie.com Officiële Selectie – 2008 Cannes Film Festival Genre: drama Release datum: 11 december 2008 Distributie: cinéart Meer informatie: Publiciteit & Marketing: cinéart Noor Pelser & Janneke De Jong Ampèrestraat 10, 1221 GJ Hilversum Tel: +31 (0)35 6463046 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Persmappen en foto’s staan op: www.cineart.nl Persrubriek inlog: cineart / wachtwoord: film - Ampèrestraat 10 - 1221 GJ Hilversum - T: 035-6463046 - F: 035-6463040 - email: [email protected] Starring (in alphabetical order) Juan Antonio JAVIER BARDEM Judy Nash PATRICIA CLARKSON Maria Elena PENÉLOPE CRUZ Mark Nash KEVIN DUNN Vicky REBECCA HALL Cristina SCARLETT JOHANSSON Doug CHRIS MESSINA Co-Starring (in alphabetical order) ZAK ORTH CARRIE PRESTON PABLO SCHREIBER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON GARETH WILEY STEPHEN TENENBAUM Co-Producers HELEN ROBIN Executive Producer JAUME ROURES Co-Executive Producers JACK ROLLINS CHARLES H. -

Barcode Title Language Category Allafri001 Tweetalige Skool

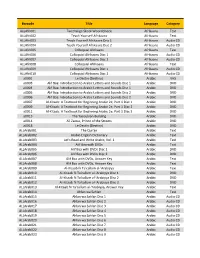

Barcode Title Language Category ALLAfri001 Tweetalige Skool-Woordeboek Afrikaans Text ALLAfri002 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri003 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri004 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri005 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri006 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri007 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri008 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri009 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri010 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD a0001 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic VHS a0003 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0004 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0005 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0006 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0007 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0009 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0011 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 3 Arabic DVD a0013 The Yacoubian Building Arabic DVD a0014 Ali Zaoua, Prince of the Streets Arabic DVD a0018 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic DVD ALLArab001 The Qur'an Arabic Text ALLArab002 Arabic-English Dictionary Arabic Text ALLArab003 Let's Read and Write Arabic, Vol. 1 Arabic Text ALLArab004 Alif Baa with DVDs Arabic Text ALLArab005 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 1 Arabic DVD ALLArab006 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 2 Arabic -

LANGUAGE MEDIA CENTER FILM LIST Title Language/Film Type Please Note That Titles Are Listed Based on DVD Cover

LANGUAGE MEDIA CENTER FILM LIST Title Language/Film Type Please note that titles are listed based on DVD cover. Some titles are in English and some are in the language used in the film. It is helpful to know both titles! 400 Blows FRENCH 8 Women FRENCH Al Otro Lado (To the other Side) SPANISH All about my Mother SPANISH Amores Perros SPANISH Antonio Gaudi ENGLISH DOCUMENTARY Argentina Y Sus Imagenes SPANISH DOCUMENTARY Belle Epoque SPANISH Bolivar Soy Yo SPANISH Bon Voyage FRENCH Bread and Roses SPANISH Bride Wore Black FRENCH Brotherhood of the Wolf FRENCH Buena Vista Social Club ENGLISH DOCUMENTARY Butterfly SPANISH Camille Claudel FRENCH Carlos Saura's Flamenco Trilogy SPANISH Carol's Journey (El viaje de Carol) SPANISH Cinema, Aspirins, and Vultures PORTUGUESE Cities of Light: The Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain ENGLISH DOCUMENTARY City of No Limits SPANISH Colombia Y Sus Imagenes SPANISH DOCUMENTARY Common Ground SPANISH Dali Dimension: Decoding The Mind of a Genius ENGLISH DOCUMENTARY Dancer Upstairs SPANISH Dark Blue Almost Black SPANISH Dark Habits SPANISH Das Boot GERMAN Del Amor Y Otros Demonios SPANISH Don Giovanni OPERA Dos Colombianos SPANISH Dust to Dust SPANISH Ecuador Y Sus Imagenes SPANISH DOCUMENTARY El Bola SPANISH El Crimen Del Padre Amaro SPANISH El Dia de las Madres / Los Problemas de Mama SPANISH El Espejo Enterrado ("The Buried Mirror") SPANISH El Gato Con Botas SPANISH Fausto 5.0 SPANISH Flamenco SPANISH Flores de Otro Mundo SPANISH Fourth Man DUTCH Frida ENGLISH God is Brazilian PORTUGUESE Goya: Crazy Like a Genius -

Performance Intertextualities in Pedro Almodóvar’S Todo Sobre Mi Madre

This is a repository copy of (Dis)locating Spain: Performance Intertextualities in Pedro Almodóvar’s Todo sobre mi madre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/114710/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Wheeler, DG (2018) (Dis)locating Spain: Performance Intertextualities in Pedro Almodóvar’s Todo sobre mi madre. JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, 58 (1). pp. 91-117. ISSN 2578-4919 https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2018.0072 © 2018 by the University of Texas Press, This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in Cinema Journal. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2018.0072 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Abstract: Almodóvar’s unique status within Spanish, European and world cinema(s) issues a methodological challenge to existing taxonomies. Building upon Tim Bergfelder’s distinction between reputedly “open” Hollywood films and “culturally specific” European fare, this article focuses on the production and reception of Todo sobre mi madre/All about my Mother (Pedro Almodóvar, 1999). -

Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

University of Bath PHD The Representation of Migrants in Contemporary Spanish Cinema Guillén Marín, Clara Award date: 2015 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 THE REPRESENTATION OF MIGRANTS IN CONTEMPORARY SPANISH CINEMA Clara Guillén Marín Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies University of Bath May 2015 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with the author. A copy of this thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author.