Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Pu'u Wa'awa'a Biological Assessment

PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A, NORTH KONA, HAWAII Prepared by: Jon G. Giffin Forestry & Wildlife Manager August 2003 STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FORESTRY AND WILDLIFE TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. ii GENERAL SETTING...................................................................................................................1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Land Use Practices...............................................................................................................1 Geology..................................................................................................................................3 Lava Flows............................................................................................................................5 Lava Tubes ...........................................................................................................................5 Cinder Cones ........................................................................................................................7 Soils .......................................................................................................................................9 -

Cinema Medeia Nimas

Cinema Medeia Nimas www.medeiafilmes.com 10.06 07.07.2021 Nocturno de Gianfranco Rosi Estreia 10 Junho Programa Cinema Medeia Nimas | 13ª edição | 10.06 — 07.07.2021 | Av. 5 de Outubro, 42 B - 1050-057 Lisboa | Telefone: 213 574 362 | [email protected] 213 574 362 | [email protected] Telefone: 42 B - 1050-057 Lisboa | 5 de Outubro, Medeia Cinema Nimas | 13ª edição 10.06 — 07.07.2021 Av. Programa Os Grandes Mestres do Cinema Italiano Ciclo: Olhares 1ª Parte Transgressivos A partir de 17 Junho A partir de 12 Junho Ciclo: O “Roman Porno” Programa sujeito a alterações de horários no quadro de eventuais novas medidas de contençãoda da propagaçãoNikkatsu da [1971-2016] COVID-19 determinadas pelas autoridades. Consulte a informação sempre actualizada em www.medeiafilmes.com. Continua em exibição Medeia Nimas 10.06 — 07.07.2021 1 Estreias AS ANDORINHAS DE CABUL ENTRE A MORTE Les Hirondelles de Kaboul In Between Dying de Zabou Breitman e Eléa Gobbé-Mévellec de Hilal Baydarov com Simon Abkarian, Zita Hanrot, com Orkhan Iskandarli, Rana Asgarova, Swann Arlaud Huseyn Nasirov, Samir Abbasov França, 2019 – 1h21 | M/14 Azerbaijão, México, EUA, 2020 – 1h28 | M/14 ESTREIA – 10 JUNHO ESTREIA – 11 JUNHO NOCTURNO --------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------- Notturno No Verão de 1998, a cidade de Cabul, no Davud é um jovem incompreendido e de Gianfranco Rosi Afeganistão, era controlada pelos talibãs. inquieto que tenta encontrar a sua família Mohsen e Zunaira são um casal de jovens "verdadeira", aquela que trará amor e Itália, França, Alemanha, 2020 – 1h40 | M/14 que se amam profundamente. Apesar significado à sua vida. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Exploring Movie Construction & Production

SUNY Geneseo KnightScholar Milne Open Textbooks Open Educational Resources 2017 Exploring Movie Construction & Production: What’s So Exciting about Movies? John Reich SUNY Genesee Community College Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Reich, John, "Exploring Movie Construction & Production: What’s So Exciting about Movies?" (2017). Milne Open Textbooks. 2. https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Milne Open Textbooks by an authorized administrator of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exploring Movie Construction and Production Exploring Movie Construction and Production What's so exciting about movies? John Reich Open SUNY Textbooks © 2017 John Reich ISBN: 978-1-942341-46-8 ebook This publication was made possible by a SUNY Innovative Instruction Technology Grant (IITG). IITG is a competitive grants program open to SUNY faculty and support staff across all disciplines. IITG encourages development of innovations that meet the Power of SUNY’s transformative vision. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks Milne Library State University of New York at Geneseo Geneseo, NY 14454 This book was produced using Pressbooks.com, and PDF rendering was done by PrinceXML. Exploring Movie Construction and Production by John Reich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Dedication For my wife, Suzie, for a lifetime of beautiful memories, each one a movie in itself. -

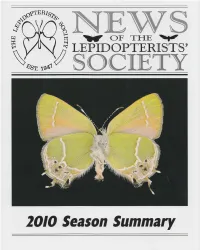

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory ........................................................................................... 3 Alaska ... ........................................ ............................................................... 3 LEPIDOPTERISTS Zone 2: British Columbia .................................................... ........................ ............ 6 Idaho .. ... ....................................... ................................................................ 6 Oregon ........ ... .... ........................ .. .. ............................................................ 10 SOCIETY Volume 53 Supplement Sl Washington ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3: Arizona ............................................................ .................................... ...... 19 The Lepidopterists' Society is a non-profo California ............... ................................................. .............. .. ................... 2 2 educational and scientific organization. The Nevada ..................................................................... ................................ 28 object of the Society, which was formed in Zone 4: Colorado ................................ ... ............... ... ...... ......................................... 2 9 May 1947 and formally constituted in De Montana .................................................................................................... 51 cember -

Los Lunes Al Sol

CULTURA , LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTAC I ÓN / CULTURE , LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ I SSN 1697-7750 · VOL . XV I \ 2016, pp. 21-36 REV I STA D E ESTU di OS CULTURALES D E LA UN I VERS I TAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I D O I : HTTP ://D X .D O I .ORG /10.6035/CLR .2016.16.2 Los lunes al sol. Retrato social de historias de vida silenciadas Mondays in the Sun. A social Portrait of Silenced Lives’ Stories DIANA AMBER * JESÚS DOMINGO ** *UNIVERSIDAD DE JAÉN . **UNIVERSIDAD DE GRANADA Artículo recibido el / Article received: 01-09-2015 Artículo aceptado el / Article accepted: 10-08-2016 RESUMEN : La película Los lunes al sol ha tenido un fuerte impacto emocional y social en el colectivo de mayores de 45 años en desempleo. Numerosas iniciativas de acceso al empleo para los mayores la usan como referente reivindicativo. El estudio busca la comprensión de la imagen que el film ofrece sobre los desem- pleados mayores, con objeto de analizar las actitudes y experiencias de los per- sonajes frente al desempleo y del propio imaginario social sobre esta temática. La metodología utilizada es el análisis fílmico desde una vertiente discursiva y analítico-reflexiva, centrada principalmente en el análisis del hecho discursivo del film. Los resultados se centran en los entresijos personales, sociales y labo- rales de sus personajes. Describen e interpretan las escenas y escenarios más re- presentativos que componen y estructuran las historias narradas. Las principales conclusiones apuntan hacia la virtud del film para visibilizar la problemática y dignificar al colectivo desde la autocrítica social de esta realidad. -

Click to Download

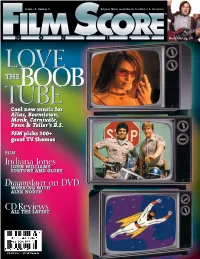

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

238 Olema Road, Fairfox, CA 94930 A61P3/00 (2006.01) A61K 48/00 (2006.01) (US)

( 1 (51) International Patent Classification: COLOSI, Peter; 238 Olema Road, Fairfox, CA 94930 A61P3/00 (2006.01) A61K 48/00 (2006.01) (US). C12N 15/86 (2006.0 1) C12N 9/02 (2006.0 1) (74) Agent: RIEGER, Dale, L. et al.; Jones Day, 250 Vesey (21) International Application Number: Street, New York, NY 10281-1047 (US). PCT/US20 19/03 1252 (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (22) International Filing Date: kind of national protection av ailable) . AE, AG, AL, AM, 08 May 2019 (08.05.2019) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, (25) Filing Language: English DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, (26) Publication Language: English HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (30) Priority Data: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, 62/669,292 09 May 2018 (09.05.2018) US OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, 62/755,207 02 November 2018 (02. 11.2018) US SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 62/802,608 07 February 2019 (07.02.2019) US TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. 62/819,414 15 March 2019 (15.03.2019) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: BIOMARIN PHARMACEUTICAL INC. -

Spanish Language Films in the Sfcc Library

SPANISH LANGUAGE FILMS IN THE SFCC LIBRARY To help you select a movie that you will enjoy, it is recommended that you look at the description of films in the following pages. You may scroll down or press CTRL + click on any of the titles below to take you directly to the description of the movie. For more information (including some trailers), click through the link to the Internet Movie Database (www.imdb.com). All films are in general circulation and in DVD format unless otherwise noted. PLEASE NOTE: Many of these films contain nudity, sex, violence, or vulgarity. Just because a film has not been rated by the MMPA, does not mean it does not contain these elements. If you are looking for a film without those elements, consider viewing one of the films on the list on the last page of the document. A Better Life (2011) Age of Beauty / Belle epoque (1992) DVD/VHS All About My Mother / Todo sobre mi madre (1999) Alone / Solas (1999) And Your Mama Too / Y tu mamá también (2001) Aura, The / El aura (2005) Bad Education / La mala educación (2004) Before Night Falls / Antes que anochezca (2000) DVD/VHS Biutiful (2010) Bolivar I Am / Bolívar soy yo (2002) Broken Embraces / Abrazos rotos (2009) Broken Silence / Silencio roto (2001) Burnt Money / Plata quemada (2000) Butterfly / La lengua de las mariposas (1999) Camila (1984) VHS media office Captain Pantoja and the Special Services / Pantaleón y las visitadoras (2000) Carancho (2010) Cautiva (2003) Cell 211 / Celda 211 (2011) Chinese Take-Out(2011) Chronicles / Crónicas (2004) City of No Limits -

The Inventory of the Dirk Bogarde Collection #923

The Inventory of the Dirk Bogarde Collection #923 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ,'.'\7\ BOGARDE, DIRK 1921 - (Derek van den Bogaerde) Purchase, February, 1989 #29A I. MANUSCRIPTS Box 1 A. BACKCLOTH; Viking, 1986, (autobiography) 1. Typescript with author's holograph revision, 13lp. (#1) 2. Index, photocopied typescript, 15 p. 3. Illustrations for book by DB: 1 original "Aunt Kitty's Room" Pen and ink with wash. Photocopies of 14 different scenes. Proof copy of 2 on 1 sheet Folder bearing holograph notes (#2) B. GENTLE OCCUPATION, Knopf, 1980, (novel) I. Typescript with author's holograph revisions, 182 p. and lp. holograph notes. {#3) Box 1/2 2. Setting copy, Typescript, some photocopied typescript, with printer's markings, 435 p. (#4,S. Box 2, #1) 3. Suggestions, Photocopy typescript, random pages, 16 p. Box 2 c. "May We Borrow Your Husband," Screenplay, 1986 (adapted by DB from Graham Greene's short story)' 1. Shooting script, mimeograph some holograph corrections, 194 p. (#2,3) 2. Scene Outline, typescript with some holograph corrections, 8-16-85(#4) 3. Additional dialogue for Stephen/Tony, carbon typescript, 2 p. Typescript, 3 p. and 2 duplicates 4. Alternate additional dialogue Stephen/Tony; carbon typescript, 3 p. 5. Letter: DB to the film's director Bob Mahoney. Photocopy TLS, 4-4-86 1 Box 2 6. 1 b/w photograph (8" x 10") of cast including DB, with note about production on verso. D. AN ORDERLY MAN, Knopf, 1983, (autobiography) 1. First draft, typescript with author's holograph revisions, 135 p. (#5) 2. First draft revision, photocopied typescript with holograph corrections, insertions, revisions, notes, captions for photographs, 150 p.