Act Therefore to Be a Virago of the Lord”: Eleventh Century Ecclesiastical Reform and New Forms and Perceptions of Lay Female Religiosity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ukrainian Orthodox Question in the USSR

The Ukrainian Orthodox Question in the USSR FRANK E. SYSYN In 1977 Father Vasyl' Romanyuk, a prisoner in the Soviet Gulag because of his struggle for religious and national rights, addressed a letter to Metropolitan Mstyslav, leader of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in the West:. Your Grace! First of all, I assure you of my devotion and humility. I declare that I consider and have always considered myself a member of the U[krainian] A[utocephalous] O[rthodox] C[hurch] in spite of the fact that I formally belonged to a different hierarchy, for it is well known that the Ukrainian Church, Orthodox as well as Catholic, is outlawed in Ukraine. Such are the barbaric ethics of the Bolsheviks. 1 The appeal was a remarkable testimony that almost fifty years after the destruction of the Ukrainian Orthodox Autocephalous Church formed in the 1920s and over thirty years after the eradication of the Church restored during the Second World War, loyalty to Ukrainian Orthodoxy still remains alive among Ukraine's believers. It also demonstrates how shared persecution has brought new ecumenical understanding between U,laainian Orthodox and Ukrainian Catholics. 'To discuss the position of Ukrainian Orthodoxy in the Soviet Union is a difficult task, for since the destruction of tens of its bishops, thousands of its priests, and tens of thousands of its lay activists in the early 1930s (and once again after the Second World War), and its forcible incorporation into the Russian Orthodox Church, it exists more as a loyalty and an Ull realised dream than as an active movement. -

Abbot Suger's Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis

DE CONSECRATIONIBUS: ABBOT SUGER’S CONSECRATIONS OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. DENIS by Elizabeth R. Drennon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth R. Drennon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Elizabeth R. Drennon Thesis Title: De Consecrationibus: Abbot Suger’s Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis Date of Final Oral Examination: 15 June 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Elizabeth R. Drennon, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Erik J. Hadley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Lisa McClain, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION I dedicate this to my family, who believed I could do this and who tolerated my child-like enthusiasm, strange mumblings in Latin, and sudden outbursts of enlightenment throughout this process. Your faith in me and your support, both financially and emotionally, made this possible. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lisa McClain for her support, patience, editing advice, and guidance throughout this process. I simply could not have found a better mentor. -

01 the Investiture Contest and the Rise of Herod Plays in the Twelfth Century

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Early Drama, Art, and Music Medieval Institute 2021 01 The Investiture Contest and the Rise of Herod Plays in the Twelfth Century John Marlin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/early_drama Part of the Medieval Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Marlin, John, "01 The Investiture Contest and the Rise of Herod Plays in the Twelfth Century" (2021). Early Drama, Art, and Music. 9. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/early_drama/9 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Medieval Institute at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Early Drama, Art, and Music by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. The Investiture Contest and the Rise of Herod Plays in the Twelfth Century John Marlin Since the publication of O. B. Hardison’s Christian Rite and Christian Drama in the Middle Ages,1 E. K. Chambers’s and Karl Young’s evolutionary models for liturgical drama’s development2 have been discarded. Yet the question remains of accounting for what Rosemary Woolf calls its “zig-zag” development,3 its apogee being the twelfth century. The growth and decline of Christmas drama is particularly intriguing, as most of Young’s samples of the simple shepherd plays, the Officium Pastores, come from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, while the earliest Christmas play he documents, from an eleventh-century Freising Cathedral manuscript, is a complete play about Herod and the Magi, the Officium Stellae. -

The Transformations of a Buddhist Symbol of Evil

ABSTRACT MALLEABLE MāRA: THE TRANSFORMATIONS OF A BUDDHIST SYMBOL OF EVIL by Michael David Nichols Despite its importance to the legend of the Buddha’s enlightenment and numerous Buddhist texts, a longitudinal, diachronic analysis of the symbol of Māra has never been done. This thesis aims to fill that gap by tracing the Evil One’s development in three spheres. Chapter one deals with Māra in the Nikāya texts, in which the deity is portrayed as a malign being diametrically opposed to the Buddha and his teachings. Chapter two discusses how that representation changes to ambivalence in certain Mahāyāna sūtras due to increased emphasis on the philosophical concepts of emptiness and non-duality. Finally, chapter three charts the results of a collision between the two differing representations of Māra in Southeast Asia. The concludes that the figure of Māra is malleable and reflects changes in doctrinal and sociological situations. Malleable Māra: The Transformations of a Buddhist Symbol of Evil A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Religion by Michael David Nichols Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2004 Adviser _______________________ Prof. Elizabeth Wilson Reader _______________________ Prof. Julie Gifford Reader _______________________ Prof. Lisa Poirier CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 2 CHAPTER ONE “MāRA OF THE MYRIAD MENACES” . 6 CHAPTER TWO “MāRA’S METAMORPHOSIS” . 24 CHAPTER THREE “MāRA MIXED UP” . 46 CONCLUSION “MāRA MULTIPLIED” . 62 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 67 ii Introduction “The eye is mine, ascetic, forms are mine…The ear is mine, ascetic, sounds are mine…The nose is mine, ascetic, odors are mine…The tongue is mine, ascetic, tastes are mine…The body is mine, ascetic, tactile objects are mine…The mind is mine, ascetic, mental phenomenon are mine…Where can you go, ascetic, to escape from me?”1 The deity responsible for these chilling lines has many names. -

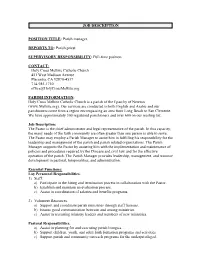

JOB DESCRIPTION POSITION TITLE: Parish Manager. REPORTS TO

JOB DESCRIPTION POSITION TITLE: Parish manager. REPORTS TO: Parish priest. SUPERVISORY RESPONSIBILITY: Full-time position. CONTACT: Holy Cross Melkite Catholic Church 451 West Madison Avenue Placentia, CA 92870-4537 714-985-1710 [email protected] PARISH INFORMATION: Holy Cross Melkite Catholic Church is a parish of the Eparchy of Newton (www.Melkite.org). Our services are conducted in both English and Arabic and our parishioners come from a region encompassing an area from Long Beach to San Clemente. We have approximately 300 registered parishioners and over 600 on our mailing list. Job Description: The Pastor is the chief administrator and legal representative of the parish. In this capacity, the many needs of the faith community are often greater than one person is able to serve. The Pastor may employ a Parish Manager to assist him in fulfilling his responsibility for the leadership and management of the parish and parish related organizations. The Parish Manager supports the Pastor by assisting him with the implementation and maintenance of policies and procedures required by the Diocese and civil law and for the effective operation of the parish. The Parish Manager provides leadership, management, and resource development in pastoral, temporalities, and administration. Essential Functions: Lay Personnel Responsibilities. 1) Staff. a) Participate in the hiring and termination process in collaboration with the Pastor. b) Establish and maintain an evaluation process. c) Assist in coordination of salaries and benefits programs. 2) Volunteer Resources. a) Support and coordinate parish ministries through staff liaisons. b) Ensure good communication between and among ministries. c) Assist in recruiting ministry leaders and members of new ministries. -

Middle Collegiate Church

Middle Collegiate Church Grace Yukich Princeton University We know that mainline Protestant churches are in decline and that urban populations are less churched than suburban and rural populations are. Middle Collegiate Church, located in the East Village in New York City, is successfully bucking these trends. It is a thriving congregation with a large, growing membership, committed clergy and lay leaders, and a diverse set of artistic, spiritual, and outreach programs. Perhaps even more surprising, Middle is increasingly attracting and engaging young adults. Around 15 percent of the church’s regular participants in weekly worship and other activities are between 18 and 35. How has Middle Church been able to combat the forces of decline that have plagued so many mainline Protestant churches, especially ones in urban areas? History and Mission of Middle Church Middle has not always been this successful. It is the oldest continuously existing Protestant church in the United States, and it has a very large endowment due to its ownership of various parts of Manhattan over the years. Still, its historic status and its financial resources have not always been enough to attract new members. Over the past 25 years, it has undergone a dramatic transformation from a dying church of only a handful of elderly members, no programming, and a decaying building to its present flourishing state. In the early 1980s, when the church’s denomination (the Reformed Church in America) and the local organization of churches of which it is a member (The Collegiate Churches of New York) were considering closing it, they brought in a new pastor—Rev. -

Ivo of Chartres, the Gregorian Reform and the Formation of the Just War Doctrine

Dominique Bauer 43 Ivo of Chartres, the Gregorian Reform and the Formation of the Just War Doctrine Dominique Bauer Senior Lecturer, Law Faculty, Tilburg University, Netherlands in cooperation with Randall Lesaffer Professor of Legal History, Tilburg University; Professor of Law, Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium 1. A Missing Link in the History of the Just War Doctrine Few will dispute that the just war doctrine historically has been among the most influen- tial and enduring legacies of the Late Middle Ages. Before the United Nations Charter of 1945, the doctrine formed the backbone of the ius ad bellum as it had been understood by writers and been paid lip service to by rulers since the Late Middle Ages.1 The just war doctrine obtained its classical outline during the thirteenth century. As in many matters of theology and political theory, Saint Thomas Aquinasʼs (1225-1274) synthesis gained canonical authority and outlived the ages as the common denominator for the doctrine. Of course, this did not mean that afterwards there were no variations on the theme. According to Aquinas, for a war to be just three conditions had to be fulfilled. First, the belligerent needed authority (auctoritas principis). In practice, this meant that only the Church or a secular prince who did not recognise a higher authority2 had the right to wage or authorise war. A ruler who did not enjoy ʻsovereigntyʼ could turn to his superior to have his rightful or supposedly rightful claim upheld. Second, a war had to be waged for a just cause (causa iusta). This could either be self-defence against prior armed ag- gression, the recovery of lost property or the restoration of injured rights. -

MATILDA of SCOTLAND (Pg

pg 1/2 Matilda of Scotland Born: 1069 Dunfermline, Scotland Married: King Henry I of England Died: 1 May 1118 Parents: Malcolm III of Scotland & Margaret Athling Matilda of Scotland[1] (born Edith; c. 1080 – 1 May 1118) was the first wife and queen consort of Henry I. Early life Matilda was born around 1080 in Dunfermline, the daughter of Malcolm III of Scotland and Saint Margaret. She was christened Edith, and Robert Curthose stood as godfather at her christening — the English queen Matilda of Flanders was also present at the font and may have been her godmother. When she was about six years old, Matilda and her sister Mary were sent to Romsey, where their aunt Cristina was abbess. During her stay at Romsey and Wilton, Matilda was much sought-after as a bride; she turned down proposals from both William de Warenne, 2nd Earl of Surrey, and Alan Rufus, Lord of Richmond. Hermann of Tournai even claims that William II Rufus considered marrying her. She was out of the monastery by 1093, when Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote to the Bishop of Salisbury ordering that the daughter of the king of Scotland be returned to the monastery that she had left. Marriage After the death of William II Rufus in August 1100, his brother Henry quickly seized the royal treasury and the royal crown. His next task was to marry, and Henry's choice fell on Matilda. Because Matilda had spent most of her life in a nunnery, there was some controversy over whether or not she had been veiled as a nun and would thus be ineligible for marriage. -

Supplementary Anselm-Bibliography 11

SUPPLEMENTARY ANSELM-BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography is supplementary to the bibliographies contained in the following previous works of mine: J. Hopkins, A Companion to the Study of St. Anselm. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1972. _________. Anselm of Canterbury: Volume Four: Hermeneutical and Textual Problems in the Complete Treatises of St. Anselm. New York: Mellen Press, 1976. _________. A New, Interpretive Translation of St. Anselm’s Monologion and Proslogion. Minneapolis: Banning Press, 1986. Abulafia, Anna S. “St Anselm and Those Outside the Church,” pp. 11-37 in David Loades and Katherine Walsh, editors, Faith and Identity: Christian Political Experience. Oxford: Blackwell, 1990. Adams, Marilyn M. “Saint Anselm’s Theory of Truth,” Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, I, 2 (1990), 353-372. _________. “Fides Quaerens Intellectum: St. Anselm’s Method in Philosophical Theology,” Faith and Philosophy, 9 (October, 1992), 409-435. _________. “Praying the Proslogion: Anselm’s Theological Method,” pp. 13-39 in Thomas D. Senor, editor, The Rationality of Belief and the Plurality of Faith. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995. _________. “Satisfying Mercy: St. Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo Reconsidered,” The Modern Schoolman, 72 (January/March, 1995), 91-108. _________. “Elegant Necessity, Prayerful Disputation: Method in Cur Deus Homo,” pp. 367-396 in Paul Gilbert et al., editors, Cur Deus Homo. Rome: Prontificio Ateneo S. Anselmo, 1999. _________. “Romancing the Good: God and the Self according to St. Anselm of Canterbury,” pp. 91-109 in Gareth B. Matthews, editor, The Augustinian Tradition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999. _________. “Re-reading De Grammatico or Anselm’s Introduction to Aristotle’s Categories,” Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, XI (2000), 83-112. -

Some Witnesses on the Gradual Evolution of the Ivonian Textual Families * Algunos Testimonios De La Evolución Gradual De Las Familias Textuales De Ivo

07. Szuromi Estudio 10/5/10 16:46 Página 201 Some Witnesses on the Gradual Evolution of the Ivonian Textual Families * Algunos testimonios de la evolución gradual de las familias textuales de Ivo Szabolcs Anzelm SZUROMI, O.PRAEM. Profesor Ordinario Pázmány Péter Catholic University. Budapest [email protected] Abstract: Ivo’s intention was to present the canon Resumen: El proyecto de Ivo de Chartres pretendía law of the Church as a whole, so as to promote the una presentación completa del derecho canónico role and work of ecclesiastical institutions, espe- de la Iglesia como instrumento que facilitase el tra- cially with regard to the care of souls and salvation bajo y la actividad de las instituciones eclesiásticas, as the final goal. This endeavor to apply the entirety con especial atención a la cura de almas y su salva- of canon law might be realized in a variety of ways, ción eterna como objetivo principal. Este plantea- and was to be fundamentally linked to the particu- miento se podía realizar de diversas maneras, pero lar features of specific ecclesiastical institutions. dependía fundamentalmente de las peculiaridades Strict paleographical and codicological analyses of concretas de cada instituto eclesial. Por otra parte, Orléans, Bibliothèque Municipal Ms. 222 (194) and el análisis detallado de los manuscritos de Orléans, Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College 393 (455) Bibliothèque Municipale 222 (194) y Cambridge, suggests convincingly that the term «textual fami- Gonville and Caius College 393 (455), muestra que lies» be used in relation to Ivo’s work. en relación con la obra de Ivo, es mejor utilizar la expresión de «familias textuales». -

'How the Corpse of a Most Mighty King…' the Use of the Death and Burial of the English Monarch

1 Doctoral Dissertation ‘How the Corpse of a Most Mighty King…’ The Use of the Death and Burial of the English Monarch (From Edward to Henry I) by James Plumtree Supervisors: Gábor Klaniczay, Gerhard Jaritz Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department and the Doctoral School of History Central European University, Budapest in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy CEU eTD Collection Budapest 2014 2 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................ 3 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 6 1. ‘JOYFULLY TAKEN UP TO LIVE WITH GOD’ THE ALTERED PASSING OF EDWARD .......................................................................... 13 1. 1. The King’s Two Deaths in MS C and the Vita Ædwardi Regis .......................... 14 1. 2. Dead Ends: Sulcard’s Prologus and the Bayeux Tapestry .................................. 24 1. 3. The Smell of Sanctity, A Whiff of Fraud: Osbert and the 1102 Translation ....... 31 1. 4. The Death in Histories: Orderic, Malmesbury, and Huntingdon ......................... 36 1. 5. ‘We Have Him’: The King’s Cadaver at Westminster ....................................... -

Ancestors of Luca Jediah WESTFALL B

Prepared by: Lincoln Westfall Lincoln Westfall 1113 Murfreesboro Rd Nicholas J. Jurian Suite 106, #316 Franklin, WESTPHALEN WESTPHALEN TN 37064 USA b. 1594 b. 1560 Printed on: 01 Jun 2004 Jurian WESTPHAL at Westphalen Prov. or at Westphalen Prov. Rhine Ancestors of Luca Jediah WESTFALL b. 12 Mar 1629 Muenster, Rhine Valley, Valley, Germany at Westphalia Province, Germany m. Germany d. 1655 at d. at Westfalen Prov. Rhine Or:1667/10/01-1669/10/01 Valley, Germany at Kingston, Ulster Co, New m. 1628 York, USA at Westphalen Prov. Rhine m. Valley, Germany Or:1652/00/00-1653/00/00 Johannes "John" at Esopus or Kingston, Jurian WESTFALL Ulster Co, NY b. Or:1655/00/00-1657/00/00 b. 1505 NOTES: at Foxhall, Kingston, Ulster at Dordrecht, Zuid Province, Co, New York, USA Hans JANSEN Holland d. b. circa 1600 d. 10 Sep 1538 Or:1719/00/00-1721/00/00 at Netherlands at Holland at Kingston, Ulster Co, New d. 1690 m. 1529 York, USA at at Holland Maritje HANSEN b. 1532 m. 28 Jun 1683 m. 1629 b. 1636 at Dordrecht, Zuid Province, at Kingston, Ulster Co, New at Netherlands at Nordstrand, Holstein, Holland 1. Extentions/continuations of this pedigree, starting York, USA b. 1513 b. 1487 Holland (Prussia) d. 23 Sep 1596 at Dordrecht, Zuid Province, at d. at Holland m. Or:1670/01/10-1680/01/10 Rymerigg (Rymeria, m. 1550 d. 1565 at at Kingston, Ulster Co, NY Rammetje?) at Dordrecht, Zuid Province, at the point marked in orange, are found on pages 2, b.