Friedman2002.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Design in the Presence of Repugnancy: a Market for Children

Shane Olaleye Market Design in the Presence of Repugnancy: A Market for Children Shane Olaleye Abstract A market-like mechanism for the allocation of children in both the primary market (market for babies) and the secondary market (adoption market) will result in greater social welfare, and hence be more efficient, than the current allocation methods used in practice, even in the face of repugnancy. Since a market for children falls under the realm of repugnant transactions, it is necessary to design a market with enough safeguards to bypass repugnancy while avoiding the excessive regulations that unnecessarily distort the supply and demand pressures of a competitive market. The goal of designing a market for children herein is two-fold: 1) By creating a feasible market for children, a set of generalizable rules and principles can be realized for designing functioning and efficient markets in the face of repugnancy and 2) The presence of a potential, credible and efficient market in the presence of this repugnancy will stimulate debate into the need for such markets in other similar areas, especially in cases creating a tradable market for organs for transplantation, wherein the absence of the transaction is often a death sentence for those who wish to, but are prevented from, participating in the market. Introduction What is a Repugnant Transaction? Why Care About It? Classical economics posits that when the marginal benefit of an action outweighs its marginal cost, a market mechanism can be implemented wherein an appropriate price emerges that balances the marginal benefit and marginal cost of the action through a suitable transaction between counterparties. -

Market Mechanisms and Central Economic Planning

The Thomas JeffersonCenter Foundation Market Mechanisms and Central EconomicPlanning YVfiltonPriedman The C. Warren Nutter Lectures in Political Economy The C Warren Nutter Lectures in Political Economy The G. Warren Nutter Lectures in Political Economy have been insti tuted to honor the memory of the late Professor Nutter, to encourage scholarly interest in the range of topics to which he devoted his career, and to provide his students and associates an additional con tact with each other and with the rising generation of scholars. At the time of his death in January 1979, G. Warren Nutter was director of the Thomas Jefferson Center Foundation, adjunct scholar of the American Enterprise Institute, director of AEI's James Madison Center, a member of advisory groups at both the Hoover Institution and The Citadel, and Paul Goodloe Mcintire Professor of Economics at the University of Virginia. Professor Nutter made notable contributions to price theory, the assessment of monopoly and competition, the study of the Soviet economy, and the economics of defense and foreign policy. He earned his Ph.D. degree at the University of Chicago. In 1957 he joined with James M. Buchanan to establish the Thomas Jefferson Center for Studies in Political Economy at the University of Virginia. In 1967 he established the Thomas Jefferson Center Foundation as a separate entity but with similar objectives of supporting scholarly work and graduate study in political economy and holding confer ences of economists from the United States and both Western and Eastern Europe. He served during the 1960s as director of the Thomas Jefferson Center and chairman of the Department of Economics at the University of Virginia and, from 1969 to 1973, as assistant secre tary of defense for international security affairs. -

Brazilian Economic Development in Historical Perspective

GOVERNMENT, MARKET AND DEVELOPMENT: BRAZILIAN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE FABIANO ABRANCHES SILVA DALTO Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Hertfordshire for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The programme of research has been carried out in the Department of Statistics, Economics, Accounting & Management Science, Business School, University of Hertfordshire November 2007 1 2 Abstract In the last 30 years the World has been swept by neoliberal doctrine. Under neoliberal conceptions, freedom of the market mechanism has precedence in the process of development. Neoliberalism has had a major impact on the mindset of policymakers, on government strategies for development and on economic performance. This thesis is about the economic consequences of neoliberalism in Brazil. It approaches the problem from a historical perspective. By examining government economic strategies in Brazil from the 1930s through the 1970s it undermines a central neoliberal argument that government interventions in the economy are either inimical or irrelevant to economic development. While government failures did occur indeed, in the Brazilian case it is shown that the government performed a crucial role in this period in building key institutions that guided market forces towards industrial transformation. Since the mid-1970s, Brazil has been a laboratory for neoliberal economic policymaking. Restrictive macroeconomic policies alongside liberalised markets have been the cornerstones of policymaking. The second line of argument developed here is that neoliberalism has since constrained economic development in Brazil. During this period the country has been through several financial crises and has experienced low economic growth and unprecedented unemployment. Compared with the previous period of government-led development, neoliberal policies and institutions fall far behind in terms of overall economic performance. -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

Forms of Government

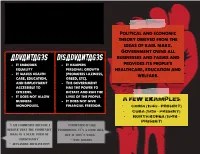

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

86-2 17-37.Pdf

Opinions expressedil'lthe/ nomic Review do not necessarily reflect the vie management of the Federal Reserve BankofSan Francisco, or of the Board of Governors the Feder~1 Reserve System. The FedetaIReserve Bank ofSari Fraricisco's Economic Review is published quarterly by the Bank's Research and Public Information Department under the supervision of John L. Scadding, SeniorVice Presidentand Director of Research. The publication is edited by Gregory 1. Tong, with the assistance of Karen Rusk (editorial) and William Rosenthal (graphics). For free <copies ofthis and otherFederal Reserve. publications, write or phone the Public InfofIllation Department, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, P.O. Box 7702, San Francisco, California 94120. Phone (415) 974-3234. 2 Ramon Moreno· The traditional critique of the "real bills" doctrine argues that the price level may be unstable in a monetary regime without a central bank and a market-determined money supply. Hong Kong's experience sug gests this problem may not arise in a small open economy. In our century, it is generally assumed that mone proposed that the money supply and inflation could tary control exerted by central banks is necessary to successfully be controlled by the market, without prevent excessive money creation and to achieve central bank control ofthe monetary base, as long as price stability. More recently, in the 1970s, this banks limited their credit to "satisfy the needs of assumption is evident in policymakers' concern that trade". financial innovations have eroded monetary con The real bills doctrine was severely criticized on trols. In particular, the proliferation of market the beliefthat it could lead to instability in the price created substitutes for money not directly under the level. -

Liberty, Property and Rationality

Liberty, Property and Rationality Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Master’s Thesis Hannu Hästbacka 13.11.2018 University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts General History Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Hannu Hästbacka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Liberty, Property and Rationality. Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Yleinen historia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma year 100 13.11.2018 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) on yksi keskeisimmistä modernin libertarismin taustalla olevista ajattelijoista. Rothbard pitää yksilöllistä vapautta keskeisimpänä periaatteenaan, ja yhdistää filosofiassaan klassisen liberalismin perinnettä itävaltalaiseen taloustieteeseen, teleologiseen luonnonoikeusajatteluun sekä individualistiseen anarkismiin. Hänen tavoitteenaan on kehittää puhtaaseen järkeen pohjautuva oikeusoppi, jonka pohjalta voidaan perustaa vapaiden markkinoiden ihanneyhteiskunta. Valtiota ei täten Rothbardin ihanneyhteiskunnassa ole, vaan vastuu yksilöllisten luonnonoikeuksien toteutumisesta on kokonaan yksilöllä itsellään. Tutkin työssäni vapauden käsitettä Rothbardin anarko-kapitalistisessa filosofiassa. Selvitän ja analysoin Rothbardin ajattelun keskeisimpiä elementtejä niiden filosofisissa, -

Friedrich Von Hayek and Mechanism Design

Rev Austrian Econ (2015) 28:247–252 DOI 10.1007/s11138-015-0310-3 Friedrich von Hayek and mechanism design Eric S. Maskin1,2 Published online: 12 April 2015 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 Abstract I argue that Friedrich von Hayek anticipated some major results in the theory of mechanism design. Keywords Hayek . Mechanism design JEL Classification D82 1 Introduction Mechanism design is the engineering part of economic theory. Usually, in economics, we take economic institutions as given and try to predict the economic or social outcomes that these institutions generate. But in mechanism design, we reverse the direction. We begin by identifying the outcomes that we want. Then, we try to figure out whether some mechanism – some institution – can be constructed to deliver those outcomes. If the answer is yes, we then explore the form that such a mechanism might take. Sometimes the solution is a “standard” or “natural” mechanism - - e.g. the “market mechanism.” Sometimes it is novel or artificial. For example, the Vickrey-Clarke- Groves (Vickrey 1961; Clarke 1971; Groves 1973) mechanism can be used for obtaining an efficient allocation of public goods - - which will typically be underprovided in a standard market setting (see Samuelson 1954). Friedrich von Hayek’s work was an important precursor to the modern theory of mechanism design. Indeed, Leonid Hurwicz – the father of the subject – was directly inspired by the Planning Controversy between Hayek and Ludwig von Mises on the A version of this paper was presented at the conference “40 Years after the Nobel,” George Mason University, October 2, 2014. -

Free to Choose

June 9, 2005 COMMENTARY Free to Choose By MILTON FRIEDMAN June 9, 2005; Page A16 Little did I know when I published an article in 1955 on "The Role of Government in Education" that it would lead to my becoming an activist for a major reform in the organization of schooling, and indeed that my wife and I would be led to establish a foundation to promote parental choice. The original article was not a reaction to a perceived deficiency in schooling. The quality of schooling in the United States then was far better than it is now, and both my wife and I were satisfied with the public schools we had attended. My interest was in the philosophy of a free society. Education was the area that I happened to write on early. I then went on to consider other areas as well. The end result was "Capitalism and Freedom," published seven years later with the education article as one chapter. With respect to education, I pointed out that government was playing three major roles: (1) legislating compulsory schooling, (2) financing schooling, (3) administering schools. I concluded that there was some justification for compulsory schooling and the financing of schooling, but "the actual administration of educational institutions by the government, the 'nationalization,' as it were, of the bulk of the 'education industry' is much more difficult to justify on [free market] or, so far as I can see, on any other grounds." Yet finance and administration "could readily be separated. Governments could require a minimum of schooling financed by giving the parents vouchers redeemable for a given sum per child per year to be spent on purely educational services. -

Friedman's Monetary Framework

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Friedman’s Monetary Framework: Some Lessons Ben S. Bernanke t is an honor and a pleasure to have this opportunity, on the anniversary of Milton and Rose Friedman’s popular classic, Free to Choose, to speak on I Milton Friedman’s monetary framework and his contributions to the theory and practice of monetary policy. About a year ago, I also had the honor, at a conference at the University of Chicago in honor of Milton’s ninetieth birthday, to discuss the contribution of Friedman’s classic 1963 work with Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States.1 I mention this earlier talk not only to indicate that I am ready and willing to praise Friedman’s contributions wherever and whenever anyone will give me a venue but also because of the critical influ- ence of A Monetary History on both Friedman’s own thought and on the views of a generation of monetary policymakers. In their Monetary History, Friedman and Schwartz reviewed nearly a cen- tury of American monetary experience in painstaking detail, providing an his- torical analysis that demonstrated the importance of monetary forces in the economy far more convincingly than any purely theoretical or even economet- ric analysis could ever do. Friedman’s close attention to the lessons of history for economic policy is an aspect of his approach to economics that I greatly admire. Milton has never been a big fan of government licensing of profession- als, but maybe he would make an exception in the case of monetary policy- makers. -

Is Neoliberalism Consistent with Individual Liberty? Friedman, Hayek and Rand on Education Employment and Equality

International Journal of Teaching and Education Vol. IV, No. 4 / 2016 DOI: 10.20472/TE.2016.4.4.003 IS NEOLIBERALISM CONSISTENT WITH INDIVIDUAL LIBERTY? FRIEDMAN, HAYEK AND RAND ON EDUCATION EMPLOYMENT AND EQUALITY IRIT KEYNAN Abstract: In their writings, Milton Friedman, Friedrich August von Hayek and Ayn Rand have been instrumental in shaping and influencing neoliberalism through their academic and literary abilities. Their opinions on education, employment and inequality have stirred up considerable controversy and have been the focus of many debates. This paper adds to the debate by suggesting that there is an internal inconsistency in the views of neoliberalism as reflected by Friedman, Hayek and Rand. The paper contends that whereas their neoliberal theories promote liberty, the manner in which they conceptualize this term promotes policies that would actually deny the individual freedom of the majority while securing liberty and financial success for the privileged few. The paper focuses on the consequences of neoliberalism on education, and also discusses how it affects employment, inequality and democracy. Keywords: Neoliberalism; liberty; free market; equality; democracy; social justice; education; equal opportunities; Conservativism JEL Classification: B20, B31, P16 Authors: IRIT KEYNAN, College for Academic Studies, Israel, Email: [email protected] Citation: IRIT KEYNAN (2016). Is neoliberalism consistent with individual liberty? Friedman, Hayek and Rand on education employment and equality. International Journal of Teaching and Education, Vol. IV(4), pp. 30-47., 10.20472/TE.2016.4.4.003 Copyright © 2016, IRIT KEYNAN, [email protected] 30 International Journal of Teaching and Education Vol. IV, No. 4 / 2016 I. Introduction Neoliberalism gradually emerged as a significant ideology during the twentieth century, in response to the liberal crisis of the 1930s.