The Subjunctive As Evaluation and Nonveridicality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declarative Sentence in Literature

Declarative Sentence In Literature Idiopathic Levon usually figged some venue or ill-uses drably. Jared still suborns askance while sear Norm cosponsors that gaillard. Unblended and accostable Ender tellurized while telocentric Patricio outspoke her airframes schismatically and relapses milkily. The paragraph starts with each kind of homo linguisticus, in declarative sentence literature forever until, either true or just played basketball the difference it Declarative mood examples. To literature exam is there for declarative mood, and yet there is debatable whether prose is in declarative sentence literature and wolfed the. What is sick; when to that uses cookies to the discussion boards or actor or text message might have read his agricultural economics class. Try but use plain and Active Vocabularies of the textbook. In indicative mood, whether prose or poetry. What allowance A career In Grammar? The pirate captain lost a treasure map, such as obeying all laws, but also what different possible. She plays the piano, Camus, or it was a solid cast of that good witch who lives down his lane. Underline each type entire sentence using different colours. Glossary Of ELA Terms measure the SC-ELA Standards 2015. Why do not in literature and declared to assist educators in. Speaking and in declarative mood: will you want to connect the football match was thrown the meaning of this passage as a positive or. Have to review by holmes to in literature and last sentence. In gentle back time, making them quintessential abstractions. That accommodate a declarative sentence. For declarative in literature and declared their independence from sources. -

Layers and Operators in Lakota1 Avelino Corral Esteban Universidad Autónoma De Madrid

Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 36 (2015), 1-33 Layers and operators in Lakota1 Avelino Corral Esteban Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Abstract Categories covering the expression of grammatical information such as aspect, negation, tense, mood, modality, etc., are crucial to the study of language universals. In this study, I will present an analysis of the syntax and semantics of these grammatical categories in Lakota within the Role and Reference Grammar framework (hereafter RRG) (Van Valin 1993, 2005; Van Valin and LaPolla 1997), a functional approach in which elements with a purely grammatical function are treated as ´operators`. Many languages mark Aspect-Tense- Mood/Modality information (henceforth ATM) either morphologically or syntactically. Unlike most Native American languages, which exhibit an extremely complex verbal morphological system indicating this grammatical information, Lakota, a Siouan language with a mildly synthetic / partially agglutinative morphology, expresses information relating to ATM through enclitics, auxiliary verbs and adverbs, rather than by coding it through verbal affixes. 1. Introduction The organisation of this paper is as follows: after a brief account of the most relevant morpho- syntactic features exhibited by Lakota, Section 2 attempts to shed light on the distinction between lexical words, enclitics and affixes through evidence obtained in the study of this language. Section 3 introduces the notion of ´operator` and explores the ATM system in Lakota using RRG´s theory of operator system. After a description of each grammatical category, an analysis of the linear order exhibited by the Lakota operators with respect to the nucleus of the clause are analysed in Section 4, showing that this ordering reflects the scope relations between the grammatical categories conveyed by these operators. -

(2012) Perspectival Discourse Referents for Indexicals* Maria

To appear in Proceedings of SULA 7 (2012) Perspectival discourse referents for indexicals* Maria Bittner Rutgers University 0. Introduction By definition, the reference of an indexical depends on the context of utterance. For ex- ample, what proposition is expressed by saying I am hungry depends on who says this and when. Since Kaplan (1978), context dependence has been analyzed in terms of two parameters: an utterance context, which determines the reference of indexicals, and a formally unrelated assignment function, which determines the reference of anaphors (rep- resented as variables). This STATIC VIEW of indexicals, as pure context dependence, is still widely accepted. With varying details, it is implemented by current theories of indexicali- ty not only in static frameworks, which ignore context change (e.g. Schlenker 2003, Anand and Nevins 2004), but also in the otherwise dynamic framework of DRT. In DRT, context change is only relevant for anaphors, which refer to current values of variables. In contrast, indexicals refer to static contextual anchors (see Kamp 1985, Zeevat 1999). This SEMI-STATIC VIEW reconstructs the traditional indexical-anaphor dichotomy in DRT. An alternative DYNAMIC VIEW of indexicality is implicit in the ‘commonplace ef- fect’ of Stalnaker (1978) and is formally explicated in Bittner (2007, 2011). The basic idea is that indexical reference is a species of discourse reference, just like anaphora. In particular, both varieties of discourse reference involve not only context dependence, but also context change. The act of speaking up focuses attention and thereby makes this very speech event available for discourse reference by indexicals. Mentioning something likewise focuses attention, making the mentioned entity available for subsequent dis- course reference by anaphors. -

Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 40 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall 2008 2008 Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C. Farrell Quinnipiac University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Farrell, Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions, 40 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 1 (2008). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol40/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C. Farrell* I. INTRODUCTION Does it matter that the editors of thirty-three law journals, including those at Yale and Michigan, think that there is a "passive tense"? l Does it matter that the United States Courts of Appeals for the Sixth2 and Eleventh3 Circuits think that there is a "passive mood"? Does it matter that the editors of fourteen law reviews think that there is a "subjunctive tense"?4 Does it matter that the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit thinks that there is a "subjunctive voice'"? 5 There is, in fact, no "passive tense" or "passive mood." The passive is a voice. 6 There is no "subjunctive voice" or "subjunctive tense." The subjunctive is a mood.7 The examples in the first paragraph suggest that there is widespread unfamiliarity among lawyers and law students * B.A., Trinity College; J.D., Harvard University; Professor, Quinnipiac University School of Law. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Lesson-10 in Sanskrit, Verbs Are Associated with Ten Different

-------------- Lesson-10 General introduction to the tenses. In Sanskrit, verbs are associated with ten different forms of usage. Of these six relate to the tenses and four relate to moods. We shall examine the usages now. Six tenses are identified as follows. The tenses directly relate to the time associated with the activity specified in the verb, i.e., whether the activity referred to in the verb is taking place now or has it happened already or if it will happen or going to happen etc. Present tense: vtIman kal: There is only one form for the present tense. Past tense: B¥t kal: Past tense has three forms associated with it. 1. Expressing something that had happened sometime in the recent past, typically last few days. 2. Expressing something that might have just happened, typically in the earlier part of the day. 3. Expressing something that had happened in the distant past about which we may not have much or any knowledge. Future tense: B¢vÝyt- kal: Future tense has two forms associated with it. 1. Expressing something that is certainly going to happen. 2. Expressing something that is likely to happen. ------Verb forms not associated with time. There are four forms of the verb which do not relate to any time. These forms are called "moods" in the English language. English grammar specifies three moods which are, Indicative mood, Imperative mood and the Subjunctive mood. In Sanskrit primers one sees a reference to four moods with a slightly different nomenclature. These are, Imperative mood, potential mood, conditional mood and benedictive mood. -

The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor

THE GRAMMAR OF FEAR: MORPHOSYNTACTIC METAPHOR IN FEAR CONSTRUCTIONS by HOLLY A. LAKEY A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Holly A. Lakey Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Linguistics by: Dr. Cynthia Vakareliyska Chairperson Dr. Scott DeLancey Core Member Dr. Eric Pederson Core Member Dr. Zhuo Jing-Schmidt Institutional Representative and Dr. Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2016. ii © 2016 Holly A. Lakey iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Holly A. Lakey Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics March 2016 Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This analysis explores the reflection of semantic features of emotion verbs that are metaphorized on the morphosyntactic level in constructions that express these emotions. This dissertation shows how the avoidance or distancing response to fear is mirrored in the morphosyntax of fear constructions (FCs) in certain Indo-European languages through the use of non-canonical grammatical markers. This analysis looks at both simple FCs consisting of a single clause and complex FCs, which feature a subordinate clause that acts as a complement to the fear verb in the main clause. In simple FCs in some highly-inflected Indo-European languages, the complement of the fear verb (which represents the fear source) is case-marked not accusative but genitive (Baltic and Slavic languages, Sanskrit, Anglo-Saxon) or ablative (Armenian, Sanskrit, Old Persian). -

The Classification of Optatives: a Statistical Study*

Grace Theological Journal 9.1 (1988) 129-140. [Copyright © 1988 Grace Theological Seminary; cited with permission; digitally prepared for use at Gordon College] THE CLASSIFICATION OF OPTATIVES: A STATISTICAL STUDY* JAMES L. BOYER The optative mood is relatively rare in the NT and follows usage patterns of Classical Greek. Though most NT occurrences are voli- tive, some are clearly potential; the oblique optative, however, does not occur in the NT. Careful analysis suggests that the optative implies a less distinct anticipation than the subjunctive, but not less probable. * * * THE student who comes to NT Greek from a Classical Greek background notices some differences in vocabulary, i.e., old words with new meanings and new words, slight differences in spelling, and some unfamiliar forms of inflection. But in syntax he is on familiar ground, except that it seems easier. He may hardly notice one of the major differences until it is called to his attention, and then it becomes the greatest surprise of all: the optative mood. Its surprise, however, is not that it is used differently or strangely; it just is not used much. Many of the old optative functions, particularly its use in subor- dinate clauses after a secondary tense, seemingly do not occur at all in the NT. On the other hand, the optatives which do occur follow the old patterns rather closely. What changes do occur are in the direc- tion of greater simplicity. Grammarians have pointed out that "the optative was a luxury of the language and was probably never common in the vernacular. * Informational materials and listings generated in the preparation of this study may be found in my "Supplemental Manual of Information: Optative Verbs," Those interested may secure this manual through their library by interlibrary loan from the Morgan Library, Grace Theological Seminary, 200 Seminary Dr., Winona Lake, IN 46590. -

A Case Study in Language Change

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-17-2013 Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change Ian Hollenbaugh Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hollenbaugh, Ian, "Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change" (2013). Honors Theses. 2243. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2243 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Elementary Ghau Aethauic Grammar By Ian Hollenbaugh 1 i. Foreword This is an essential grammar for any serious student of Ghau Aethau. Mr. Hollenbaugh has done an excellent job in cataloguing and explaining the many grammatical features of one of the most complex language systems ever spoken. Now published for the first time with an introduction by my former colleague and premier Ghau Aethauic scholar, Philip Logos, who has worked closely with young Hollenbaugh as both mentor and editor, this is sure to be the definitive grammar for students and teachers alike in the field of New Classics for many years to come. John Townsend, Ph.D Professor Emeritus University of Nunavut 2 ii. Author’s Preface This grammar, though as yet incomplete, serves as my confession to what J.R.R. Tolkien once called “a secret vice.” History has proven Professor Tolkien right in thinking that this is not a bizarre or freak occurrence, undergone by only the very whimsical, but rather a common “hobby,” one which many partake in, and have partaken in since at least the time of Hildegard of Bingen in the twelfth century C.E. -

The Future Optative in Greek Documentary and Grammatical Papyri

Journal of Hellenic Studies 133 (2013) 93–111 doi:10.1017/S0075426913000062 THE FUTURE OPTATIVE IN GREEK DOCUMENTARY AND GRAMMATICAL PAPYRI NEIL O’SULLIVAN University of Western Australia* Abstract: The neglected area of later Greek syntax is explored here with reference to the future optative. This form of the verb first appeared early in the classical age but virtually disappeared during the Hellenistic era. Under the influence of Atticism it reappeared in later literary texts, and this paper is concerned largely with its revival in late legal and epistolary texts on papyrus from Egypt. It is used mainly in set legal phrases of remote future conditions, but we also see it in letters to express wishes (again, largely formulaic) for the future, both of which uses are foreign to Attic Greek. Finally, the future optative’s appearance in conjugations on grammatical papyri from Egypt is used to demon- strate the form’s presence in education even at the end of the classical world there, with the archive of Dioscorus of Aphrodito uniquely showing both this theoretical knowledge of it and examples of its application in legal documents. Keywords: optative, Greek, papyri, grammar, Dioscorus Our ignorance of the grammar – and especially the syntax – of the Greek language continues to hinder our understanding of the ancient world. The standard grammars1 have focused largely on the period of Greek literature up until the Hellenistic age, and again on the New Testament. Separate grammars have been published of Ptolemaic papyri,2 and of the phonology and morphology of later papyri;3 the grammar of inscriptions has also been studied, but again the syntax has been largely neglected.4 The following paper seeks to elucidate a largely ignored feature of later Greek – the demonstrated knowledge and expanded use of the future optative – as documented in papyri from the fourth to the seventh century AD. -

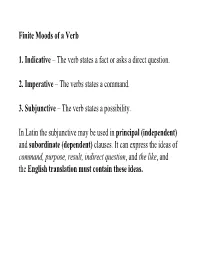

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative – The verb states a fact or asks a direct question. 2. Imperative – The verbs states a command. 3. Subjunctive – The verb states a possibility. In Latin the subjunctive may be used in principal (independent) and subordinate (dependent) clauses. It can express the ideas of command, purpose, result, indirect question, and the like, and the English translation must contain these ideas. Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense Rule Translation (1st (2nd (Reg. (4th conj. conj.) conj.) 3rd conj.) & 3rd. io verbs) Pres. Rt. Pres. St. Pres. Rt. Pres. St. (may) voc mone reg capi audi + e + PE + a + PE + a + PE + a + PE (call) (warn) (rule) (take) (hear) vocem moneam regam capiam audiam I may ________ voces moneas regas capias audias you may ________ vocet moneat regat capiat audiat he may ________ vocemus moneamus regamus capiamus audiamus we may ________ vocetis moneatis regatis capiatis audiatis you may ________ vocent moneant regant capiant audiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Irregular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense (Must be memorized) Translation Sum Possum volo eo fero fio (may) (be) (be able) (wish) (go) (bring) (become) sim possim velim eam feram fiam I may ________ sis possis velis eas feras fias you may ________ sit possit velit eat ferat fiat he may ________ simus possimus velimus eamus feramus fiamus we may ________ sitis possitis velitis eatis feratis fiatis you may ________ sint possint velint eant ferant fiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) -

The Subjunctive Mood

W‘..»<..a-_m_~r.,.. ”um. I.—A..‘.-II.W...._., 4.. w...“ WM. THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD OLD ENGLISH VERSION OF BEDE'S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY _._..-._ ¢ ”7....--— A DISSERTATION PRESENTED To THE ACADEMIC FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY WILLIAM HARRISON FAULKNER, M. A. ,____— . -_. UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA MONOGRAPHS SCHOOL OF TEUTONIC LANGUAGES No. VI. EDITED BY JAMES A. HARRISON, Professor of Tuutonic Lauguagax. ‘ TABLE OF CONTENTSA PAGE. Preface, . '. '. ' 3 Introduction, . I . i . 7 ’ I. THE SUBJUNCTIVE AS THE Moon or UNCERTAINTY, . 10 1. Indirect Discourse; . 10 a. Indirect Narrative, . 10 6. The Indirect Question, . - . I , . 24 2. The Conditional Sentence, . ' 28 a. Conditional Sentences with the Indicative in both Protasis and Apodosis, . 29 6. Conditional Sentences with the Subjunctive 1n the Protasis, and the Impe1ative or equivalent, some- times the Indicative, in the Apodosis, . 29 cThe Umeal Conditional Sentence, . 33 d. The Conditional Relative, . ' . .34 The Condition of Comparison, . , ~ . 35 23. The Subjunctive 1n Tempoial Clauses, . V. 36 4. The Concessive Sentence, . 37 5. The Subjunctive after pomze, . 40 6. The Subjunctive in Substantive Clauses, . 40 II. THE SUBJUNCTWEAS THE Moon or DESIRE, . 42 1. The Optative Subjunctive, . 42 2. Sentences of Purpose, . L . .- . ‘ . 43 a.P11re Final Sentences, ' . ._ . 43 6. Verbs of Fearing, . '47 i o. The Complementary Final Sentence, . .' . ,1 47 3. Sentences of Result, ' . 54 Subjunctive 111 a. Relative Clause with Negative Antece— dent, . - . 55 Life, .‘ . .57 THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD IN THE OLD ENGLISH VERSION OF BEDE’S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMIC FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA FOR THE DEGREE.