The Unmaking of a Modern Synthesis: Noam Chomsky, Charles Hockett, and the Politics of Behaviorism, 1955–1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

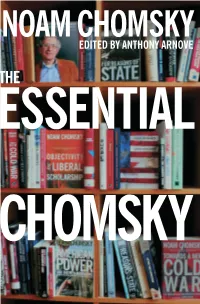

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

A Naturalist Reconstruction of Minimalist and Evolutionary Biolinguistics

A Naturalist Reconstruction of Minimalist and Evolutionary Biolinguistics Hiroki Narita & Koji Fujita Kinsella & Marcus (2009; K&M) argue that considerations of biological evo- lution invalidate the picture of optimal language design put forward under the rubric of the minimalist program (Chomsky 1993 et seq.), but in this article it will be pointed out that K&M’s objection is undermined by (i) their misunderstanding of minimalism as imposing an aprioristic presumption of optimality and (ii) their failure to discuss the third factor of language design. It is proposed that the essence of K&M’s suggestion be reconstructed as the sound warning that one should refrain from any preconceptions about the object of inquiry, to which K&M commit themselves based on their biased view of evolution. A different reflection will be cast on the current minima- list literature, arguably along the lines K&M envisaged but never completed, converging on a recommendation of methodological (and, in a somewhat unconventional sense, metaphysical) naturalism. Keywords: evolutionary/biological adequacy; language evolution; metho- dological/metaphysical naturalism; minimalist program; third factor of language design 1. Introduction A normal human infant can learn any natural language(s) he or she is exposed to, whereas none of their pets (kittens, dogs, etc.) can, even given exactly the same data from the surrounding speech community. There must be something special, then, to the genetic endowment of human beings that is responsible for the emer- gence of this remarkable linguistic capacity. Human language is thus a biological object that somehow managed to come into existence in the evolution of the hu- man species. -

Myrmecology in the Internet: Possibilities of Information Gathering

Beitr. Ent. Keltern ISSN 0005 - 805X Beitr. Ent. 55 (2005) 2 485 55 (2005) 2 S. 485 - 498 27.12.2005 Myrmecology in the internet: Possibilities of information gathering (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) with 12 tables CHRISTIANA KLINGENBERG and MANFRED VERHAAGH Summary A well advanced information system about ants exists on the internet. Many myrmecologists all over the world offer useful information as text files, images or databases. A good part of the information focuses on re- gional faunas and biogeographic regions, with updated species checklists and geographic distribution maps. Many internet sites deal with specific ant groups or single genera and provide dichotomous and sometimes interactive identification keys, extensive information about the biology and/or geographic distribution of the species. Text information is often illustrated with images of living or dry mounted ants. Additionally, detailed pages about anatomy, mounting of ants, colony husbandry or ant conservation (red lists) can be found. In discussion forums it is possible to exchange facts and thoughts about all myrmecological facets with other interested people. A special offer for taxonomists is the increasing number of databases about museum collections and their type catalogues. Zusammenfassung Für Ameisen gibt es mittlerweile ein sehr gut entwickeltes Informationssystem im Internet. Weltweit bieten zahlreiche Myrmekologen brauchbare Informationen in Form von Textbeiträgen, Bildern und Datenbanken an. Ein guter Teil der Information beschäftigt sich mit regionalen Faunen bzw. biogeographischen Regionen, z.B. in Form von Artenlisten und Verbreitungskarten. Viele Internetseiten handeln auch spezielle Ameisentaxa ab, stellen dichotome oder gar interaktive Bestimmungsschlüssel vor und offerieren ausführliche Informationen zur Biologie und Verbreitung der Arten. Die Texte werden häufig durch Bilder präparierter oder lebender Ameisen ergänzt. -

James K. Wetterer

James K. Wetterer Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458 Phone: (561) 799-8648; FAX: (561) 799-8602; e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, Seattle, WA, 9/83 - 8/88 Ph.D., Zoology: Ecology and Evolution; Advisor: Gordon H. Orians. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY, East Lansing, MI, 9/81 - 9/83 M.S., Zoology: Ecology; Advisors: Earl E. Werner and Donald J. Hall. CORNELL UNIVERSITY, Ithaca, NY, 9/76 - 5/79 A.B., Biology: Ecology and Systematics. UNIVERSITÉ DE PARIS III, France, 1/78 - 5/78 Semester abroad: courses in theater, literature, and history of art. WORK EXPERIENCE FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY, Wilkes Honors College 8/04 - present: Professor 7/98 - 7/04: Associate Professor Teaching: Principles of Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, Human Ecology, Environmental Studies, Tropical Ecology, Biodiversity, Life Science, and Scientific Writing 9/03 - 1/04 & 5/04 - 8/04: Fulbright Scholar; Ants of Trinidad and Tobago COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, Department of Earth and Environmental Science 7/96 - 6/98: Assistant Professor Teaching: Community Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, and Tropical Ecology WHEATON COLLEGE, Department of Biology 8/94 - 6/96: Visiting Assistant Professor Teaching: General Ecology and Introductory Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Museum of Comparative Zoology 8/91- 6/94: Post-doctoral Fellow; Behavior, ecology, and evolution of fungus-growing ants Advisors: Edward O. Wilson, Naomi Pierce, and Richard Lewontin 9/95 - 1/96: Teaching: Ethology PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology 7/89 - 7/91: Research Associate; Ecology and evolution of leaf-cutting ants Advisor: Stephen Hubbell 1/91 - 5/91: Teaching: Tropical Ecology, Introduction to the Scientific Method VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY, Department of Psychology 9/88 - 7/89: Post-doctoral Fellow; Visual psychophysics of fish and horseshoe crabs Advisor: Maureen K. -

Borowiec Et Al-2020 Ants – Phylogeny and Classification

A Ants: Phylogeny and 1758 when the Swedish botanist Carl von Linné Classification published the tenth edition of his catalog of all plant and animal species known at the time. Marek L. Borowiec1, Corrie S. Moreau2 and Among the approximately 4,200 animals that he Christian Rabeling3 included were 17 species of ants. The succeeding 1University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA two and a half centuries have seen tremendous 2Departments of Entomology and Ecology & progress in the theory and practice of biological Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, classification. Here we provide a summary of the NY, USA current state of phylogenetic and systematic 3Social Insect Research Group, Arizona State research on the ants. University, Tempe, AZ, USA Ants Within the Hymenoptera Tree of Ants are the most ubiquitous and ecologically Life dominant insects on the face of our Earth. This is believed to be due in large part to the cooperation Ants belong to the order Hymenoptera, which also allowed by their sociality. At the time of writing, includes wasps and bees. ▶ Eusociality, or true about 13,500 ant species are described and sociality, evolved multiple times within the named, classified into 334 genera that make up order, with ants as by far the most widespread, 17 subfamilies (Fig. 1). This diversity makes the abundant, and species-rich lineage of eusocial ants the world’s by far the most speciose group of animals. Within the Hymenoptera, ants are part eusocial insects, but ants are not only diverse in of the ▶ Aculeata, the clade in which the ovipos- terms of numbers of species. -

Medical Entomology in Brief

Medical Entomology in Brief Dr. Alfatih Saifudinn Aljafari Assistant professor of Parasitology College of Medicine- Al Jouf University Aim and objectives • Aim: – To bring attention to medical entomology as important biomedical science • Objective: – By the end of this presentation, audience could be able to: • Understand the scope of Medical Entomology • Know medically important arthropods • Understand the basic of pathogen transmission dynamic • Medical Entomology in Brief- Dr. Aljafari (CME- January 2019) In this presentation • Introduction • Classification of arthropods • Examples of medical and public health important species • Insect Ethology • Dynamic of disease transmission • Other application of entomology Medical Entomology in Brief- Dr. Aljafari (CME- January 2019) Definition • Entomology: – The branch of zoology concerned with the study of insects. • Medical Entomology: – Branch of Biomedical sciences concerned with “ArthrobodsIn the past the term "insect" was more vague, and historically the definition of entomology included the study of terrestrial animals in other arthropod groups or other phyla, such, as arachnids, myriapods, earthworms, land snails, and slugs. This wider meaning may still be encountered in informal use. • At some 1.3 million described species, insects account for more than two-thirds of all known organisms, date back some 400 million years, and have many kinds of interactions with humans and other forms of life on earth Medical Entomology in Brief- Dr. Aljafari (CME- January 2019) Arthropods and Human • Transmission of infectious agents • Allergy • Injury • Inflammation • Agricultural damage • Termites • Honey • Silk Medical Entomology in Brief- Dr. Aljafari (CME- January 2019) Phylum Arthropods • Hard exoskeleton, segmented bodies, jointed appendages • Nearly one million species identified so far, mostly insects • The exoskeleton, or cuticle, is composed of chitin. -

The Language Faculty – Mind Or Brain?

The Language Faculty – Mind or Brain? TORBEN THRANE Aarhus University, School of Business, Denmark Artiklens sigte er at underkaste Chomskys nyskabende nominale sammensætning – “the mind/brain” – en nøjere undersøgelse. Hovedargumentet er at den skaber en glidebane, således at det der burde være en funktionel diskussion – hvad er det hjernen gør når den behandler sprog? – i stedet bliver en systemdiskussion – hvad er den interne struktur af den menneskelige sprogevne? Argumentet søges ført igennem under streng iagttagelse af de kognitive videnskabers opfattelse af information og repræsentation, specielt som forstået af den amerikanske filosof Frederick I. Dretske. 1. INTRODUCTION Cartesian dualism is dead, but the central problems it was supposed to solve persist: What kinds of substances exist? Are bodily things (only) physical, mental ‘things’ (only) metaphysical? How is the mental related to the physical? Although “we are all materialists now”, such questions still need answers, and they still need answers from within realist and naturalist bounds to count as scientific. Linguistics is a discipline that may be expected to contribute with answers to such questions. No one in their right mind would deny that our ability to acquire and use human language is lodged between our ears – inside our heads. That is, in our brains and/or minds. In some quarters it has been customary for the past 50 odd years or so to regard this ability as a distinct and dedicated cognitive ability on a par with our abilities to see (vision) or to keep our balance (equilibrioception), and to refer to it as the Human Language Faculty (HLF). This has been the axiomatic starting point for the development of main stream generative linguistics as founded by Chomsky in 1955 in what I shall refer to as ‘Chomsky’s programme’. -

The Role of Affect in Language Development∗

The Role of Affect in Language Development∗ Stuart G. SHANKER and Stanley I. GREENSPAN BIBLID [0495-4548 (2005) 20: 54; pp. 329-343] ABSTRACT: This paper presents the Functional/Emotional approach to language development, which explains the process leading up to the core capacities necessary for language (e.g., pattern-recognition, joint attention); shows how this process leads to the formation of internal symbols; and how it shapes and is shaped by the child’s development of language. The heart of this approach is that, through a series of affective transfor- mations, a child develops these core capacities and the capacity to form meaningful symbols. Far from be- ing a sudden jump, the transition from pre-symbolic communication to language is enabled by the advances taking place in the child’s affective gesturing. Key words: Functional/Emotional hypothesis; affective transformations; usage-based linguistics; pattern-recognition; joint attention; learning-based interactions; nativism; autism 1. The F/E View of Language Development Chomsky began Cartesian Linguistics with the following quotation from Whitehead’s Science and the Modern World: A brief, and sufficiently accurate, description of the intellectual life of the European races during the succeeding two centuries and a quarter up to our own times is that they have been living upon the accumulated capital of ideas provided for them by the genius of the seventeenth cen- tury (Chomsky 1967). Chomsky was certainly right: both in regards to the accuracy of Whitehead’s ob- servation, and in regards to the significance of this outlook for Chomsky’s whole ap- proach to language acquisition. -

Acarology, the Study of Ticks and Mites

Acarology, the study of ticks and mites Ecophysiology, the study of the interrelationship between Actinobiology, the study of the effects of radiation upon an organism's physical functioning and its environment living organisms Edaphology, a branch of soil science that studies the Actinology, the study of the effect of light on chemicals influence of soil on life Aerobiology, a branch of biology that studies organic Electrophysiology, the study of the relationship between particles that are transported by the air electric phenomena and bodily processes Aerology, the study of the atmosphere Embryology, the study of embryos Aetiology, the medical study of the causation of disease Entomology, the study of insects Agrobiology, the study of plant nutrition and growth in Enzymology, the study of enzymes relation to soil Epidemiology, the study of the origin and spread of Agrology, the branch of soil science dealing with the diseases production of crops. Ethology, the study of animal behavior Agrostology, the study of grasses Exobiology, the study of life in outer space Algology, the study of algae Exogeology, the study of geology of celestial bodies Allergology, the study of the causes and treatment of Felinology, the study of cats allergies Fetology, the study of the fetus Andrology, the study of male health Formicology, the study of ants Anesthesiology, the study of anesthesia and anesthetics Gastrology or Gastroenterology, the study of the Angiology, the study of the anatomy of blood and lymph stomach and intestines vascular systems Gemology, -

Sociogenomics on the Wings of Social Insects Sainath Suryanarayanan

HoST - Journal of History of Science and Technology Vol. 13, no. 2, December 2019, pp. 86-117 10.2478/host-2019-0014 SPECIAL ISSUE ANIMALS, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY: MULTISPECIES HISTORIES OF SCIENTIFIC AND SOCIOTECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE-PRACTICES The Social Evolving: Sociogenomics on the Wings of Social Insects Sainath Suryanarayanan University of Wisconsin-Madison [email protected] Abstract: This paper excavates the epistemological and ontological foundations of a rapidly emerging field called sociogenomics in relation to the development of social insects as models of social behavior. Its center-stage is “the genome,” where social and environmental information and genetic variation interact to influence social behavior through dynamic shifts in gene expression across multiple bodies and time-scales. With the advent of whole-genome sequencing technology, comparative genomics, and computational tools for mining patterns of association across widely disparate datasets, social insects are being experimented with to identify genetic networks underlying autism, novelty-seeking and aggression evolutionarily shared with humans. Drawing on the writings of key social insect biologists, and historians and philosophers of science, I investigate how the historical development of social insect research on wasps, ants and bees shape central approaches in sociogenomics today, in particular, with regards to shifting understandings of “the individual” in relation to “the social.” Keywords: sociogenomics; social insect; sociobiology; postgenomics; biology and society © 2019 Sainath Suryanarayanan. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Sainath Suryanarayanan 87 Introduction …I believe that the difficulty in studying the genetic basis of social behavior demands a bold, new initiative, which I call sociogenomics. -

New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind Noam Chomsky Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651476 - New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind Noam Chomsky Frontmatter More information New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind This book is an outstanding contribution to the philosophical study of language and mind, by one of the most influential thinkers of our time. In a series of penetrating essays, Noam Chomsky cuts through the confusion and prejudice which has infected the study of language and mind, bringing new solutions to traditional philosophical puzzles and fresh perspectives on issues of general interest, ranging from the mind–body problem to the unification of science. Using a range of imaginative and deceptively simple linguistic ana- lyses, Chomsky argues that there is no coherent notion of “language” external to the human mind, and that the study of language should take as its focus the mental construct which constitutes our knowledge of language. Human language is therefore a psychological, ultimately a “biological object,” and should be analysed using the methodology of the natural sciences. His examples and analyses come together in this book to give a unique and compelling perspective on language and the mind. is Institute Professor at the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Professor Chomsky has written and lectured extensively on a wide range of topics, including linguistics, philosophy, and intellectual history. His main works on linguistics include: Syntactic Structures; Current Issues in Linguistic Theory; Aspects of the Theory of Syntax; Cartesian Linguistics; Sound Pattern of English (with Morris Halle); Language and Mind; Reflections on Language; The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory; Lec- tures on Government and Binding; Modular Approaches to the Study of the Mind; Knowledge of Language: its Nature, Origins and Use; Language and Problems of Knowledge; Generative Grammar: its Basis, Development and Prospects; Language in a Psychological Setting; Language and Prob- lems of Knowledge; and The Minimalist Program. -

CHOMSKY, Noam Avram (1928- ) Forthcoming in the Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, 1860-1960 Ed., Ernest Lepore, Thoemmes Press, 2004

CHOMSKY, Noam Avram (1928- ) Forthcoming in the Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, 1860-1960 ed., Ernest LePore, Thoemmes Press, 2004. Noam Chomsky was born to Dr. William (Zev) Chomsky and Elsie Simonofsky in Philadelphia on December 7, 1928. His father emigrated to the United States from Russia. William was an eminent scholar, author of the study Hebrew, the Eternal Language (1957), as well as numerous other works on the history and teaching of Hebrew. Noam entered the University of Pennsylvania in 1945. There he came in contact with Zelig Harris, a prominent linguist and the founder of the first linguistics department in the United States (at the University of Pennsylvania). In 1947 Chomsky decided to major in linguistics, and in 1949 he began his graduate studies in that field. His BA honor’s thesis Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew (1949, revised as an MA thesis in 1951) contains several ideas that foreshadow Chomsky’s later work in generative grammar. In 1949 he married the linguist Carol Schatz. During the years 1951 to 1955 Chomsky was a Junior Fellow of the Harvard University Society of Fellows, where he completed his PhD dissertation entitled Transformational Analysis (1955; published as part of The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory in 1975). Chomsky received a faculty position at MIT in 1955 and he has been teaching there ever since. In 1961 he was appointed full professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics; the graduate program in linguistics began the same year. In 1966 he was appointed Ferrari Ward Professor of Linguistics. In 1976, the linguistics and philosophy programs at MIT were merged and the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy was created; this has been Chomsky’s home department ever since.