Download Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turbulence in the Gulf

Come and see us at the Dubai Airshow on Stand 2018 AEROSPACE November 2017 FLYING FOR THE DARK SIDE IS MARS GETTING ANY CLOSER? HYBRID-ELECTRIC PROPULSION www.aerosociety.com November 2017 Volume 44 Number 11 Volume TURBULENCE IN THE GULF SUPERCONNECTOR AIRLINES BATTLE HEADWINDS Royal Aeronautical Society Royal Aeronautical N EC Volume 44 Number 11 November 2017 Turbulence in Is Mars getting any 14 the Gulf closer? How local politics Sarah Cruddas and longer-range assesses the latest aircraft may 18 push for a human impact Middle mission to the Red East carriers. Planet. Are we any Contents Clément Alloing Martin Lockheed nearer today? Correspondence on all aerospace matters is welcome at: The Editor, AEROSPACE, No.4 Hamilton Place, London W1J 7BQ, UK [email protected] Comment Regulars 4 Radome 12 Transmission The latest aviation and Your letters, emails, tweets aeronautical intelligence, and feedback. analysis and comment. 58 The Last Word Short-circuiting electric flight 10 Antenna Keith Hayward considers the Howard Wheeldon looks at the current export tariff spat over MoD’s planned Air Support to the Bombardier CSeries. Can a UK low-cost airline and a US start-up bring electric, green airline travel Defence Operational Training into service in the next decade? On 27 September easyJet revealed it had (ASDOT) programme. partnered with Wright Electric to help develop a short-haul all-electric airliner – with the goal of bringing it into service within ten years. If realised, this would represent a game-changing leap for aviation and a huge victory for aerospace Features Cobham in meeting or even exceeding its sustainable goals. -

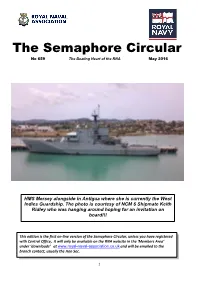

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

Military History

GRUB STREET Military History 2015/2016 Welcome to our new catalogue and thank you for your continued support of our list. Here is a reminder of the praise we’ve received in the past: GRUB STREET NEW BOOKS & STOCKLIST ‘Many readers will already have Grub Street books on their shelves, the publisher having cut a well-deserved niche for accuracy and JANUARY 2015–JANUARY 2016 readability – not an easy balance. They have an enviable reputation for well-researched works that are difficult to put down.’ Flypast CONTENTS ‘Grub Street is a publisher to be congratulated for reprinting New Titles 2 important books.’ Cross & Cockade International Bestselling Ebooks 21 Ebooks 23 ‘Some of the most valuable, and well-researched books in my library are those published by Grub Street. Although a publishing company Illustrated backlist 24 of modest size, they have consistently produced a list of titles WW2 – Battle of Britain 24 that have filled gaps in the marketplace.’ Tony Holmes, Jets WW2 – Bomber Command 25 WW2 – General Interest 26 ‘The GOGS (Gods of Grub Street) have maintained an awesome quantity and quality of production.’ Cartoons 27 The Aerodrome WW1/Modern Aviation 28 ‘Books from Grub Street can always be relied upon to be the A-Z Backlist by Title 29 very best in their class.’ The Bulletin of the Military Historical Society All trade orders should be sent to: All correspondence should be addressed to: ‘For some time now Grub Street have been producing fantastic Littlehampton Book Services Ltd Grub Street Ltd Faraday Close 4 Rainham Close books on the classic British war jets.’ Durrington London SW11 6SS War History Online Worthing Tel: 0207 924 3966/738 1008 West Sussex Fax: 0207 738 1009 BN13 3RB Email: [email protected] Tel: 01903 828500 Web: www.grubstreet.co.uk Fax: 01903 828801 Twitter: @grub_street From time to time we have signed editions of our titles. -

The Navy Vol 69 No 3 Jul 2007

JUL–SEP 2007 (including GST) www.netspace.net.au/~navyleag VOLUME 69 NO. 3 $5.45 The Battle of Britain – The AWD’s A Seapower Victory and Our Real Frontier The German Navy Today The 2007 Annual Halfway Creswell Around the Oration World in Eighty days Australia’s Leading Naval Magazine Since 1938 /"7"-/""777""-/&5803,4 /&58033,4 5)& %0.*/"/$&%0.*/"/$$& 0' $0..6/*$"5*0/4$0..6/*$""55*0/4 */ ."3*5*.& 01&3"5*0/4011&3""55*0/4 5IF 3PZBM 3PZBM"VTUSBMJBO "VTUSBMJBO /BWZµT/BWZµT 4FB 1PXFS 1PXFS$FOUSF $FOUSF ""VTUSBMJB VTUSBMJB XJUXJUIIU UIFIF BTBTTJTUBODFTTJTUBODF PG UUIFIF 4D4DIPPMIPPM PG )VNBOJUJFT BOE 4PDJ4PDJBMJBM 4DJFODFT 66OJWFSTJUZOJWFSTJUZ PG //FXFX4 4PVU4PVUI UI 88BMFTBMFTMU BU U UIFI"IF ""VTUSBMJBOVTUUSBMJBOMJ %%FG%FGFODF GFODF' 'PSDFPSDF ""DBEFNZ DBEFNZ JT IPTIPTUJOHUJOH U UIFIF ¾G¾GUIUI CJFOOJBM ,JOH)BMM //BWBMBWBM )JT)JTUPSZUPSZ $POG$POGFSFODF FSFODF +VM+VMZZ BOE +VM+VMZZ 5IJT XJMM CF B NBNBKPSKPS JJOUFSOBUJPOBMOUFSOBUJPOBM DPOGDPOGFSFODFFSFODF XJUXJUII EJTEJTUJOHVJTIFEUJOHVJTIFE TQFBLTQFBLFSTFFST GSGSPNPN ""VTUSBMJB VTUSBMJB $BOBEB UUIFIF 66OJUFEOJUFE ,JOHEPN BOE U UIFIF 66OJUFEOJUFE 44UBUFTUBUFT PG "NFS"NFSJDBJDB 5IF LLFZOPUFFZOPUF TQFBLFSTQFBLFS XJMM CF 1S1SPGFTTPSPGFTTPS //".". 33PEHFS PEHFS BVUBVUIPSIPS PG UUIFIF NVDNVDIIBBDDMBJNFE NVMUJWNVMUJWPMVNFPMVNF ""//BWBMBWWBBM )JT)JTUPSZUPSPSZZ PG #S#SJUBJOSJJUUBBJO 5IF DPOGDPOGFSFODFFSFODF QSQSPHSBNPHSBN XJMM BEESBEESFTTFTT UUIFIF TIJGTIJGUJOHUJOH EFNBOET GGBDJOHBDJOHH CPUCPUII OBUJPOBM BOE DPNCJOFE JOUJOUFSOBUJPOBMFSOBUJPOBM TFB QPQPXFS XFS UUPHFUIFSPHFUIFS XJUXJUII DBTF TTUVEJFTUVEJFT -

Military Aircraft Markings Update Number 76, September 2011

Military Aircraft Markings Update Number 76, September 2011 Serial Type (other identity) [code] Owner/operator, location or fate N6466 DH82A Tiger Moth (G-ANKZ) Privately owned, Compton Abbas T7842 DH82A Tiger Moth II (G-AMTF) Privately owned, Westfield, Surrey DE623 DH82A Tiger Moth II (G-ANFI) Privately owned, Cardiff KK116 Douglas Dakota IV (G-AMPY) AIRBASE, Coventry TD248 VS361 Spitfire LF XVIE (7246M/G-OXVI) [CR-S] Spitfire Limited, Humberside TX310 DH89A Dragon Rapide 6 (G-AIDL) Classic Flight, Coventry VN799 EE Canberra T4 (WJ874/G-CDSX) AIRBASE, Coventry VP981 DH104 Devon C2 (G-DHDV) Classic Flight, Coventry WA591 Gloster Meteor T7 (7917M/G-BWMF) [FMK-Q] Classic Flight, Coventry WB188 Hawker Hunter GA11 (WV256/G-BZPB) AIRBASE, Coventry WD413 Avro 652A Anson T21 (7881M/G-VROE) Classic Flight, Coventry WK163 EE Canberra B2/6 (G-BVWC) AIRBASE, Coventry WK436 DH112 Venom FB50 (J-1614/G-VENM) Classic Flight, Coventry WM167 AW Meteor NF11 (G-LOSM) Classic Flight, Coventry WR470 DH112 Venom FB50 (J-1542/G-DHVM) Classic Flight, Coventry WT722 Hawker Hunter T8C (G-BWGN) [878/VL] AIRBASE, Coventry WV318 Hawker Hunter T7B (9236M/G-FFOX) WV318 Group, Cotswold Airport WZ798 Slingsby T38 Grasshopper TX1 Privately owned, stored Hullavington XA109 DH115 Sea Vampire T22 Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre XE665 Hawker Hunter T8C (G-BWGM) [876/VL] Classic Flight, Coventry XE689 Hawker Hunter GA11 (G-BWGK) [864/VL] AIRBASE, Coventry XE985 DH115 Vampire T11 (WZ476) Privately owned, New Inn, Torfaen XG592 WS55 Whirlwind HAS7 [54] Task Force Adventure -

The Economics of the UK Aerospace Industry: a Transaction Cost Analysis

The economics of the UK aerospace industry: A transaction cost analysis of defence and civilian firms Ian Jackson PhD Department of Economics and Related Studies University of York 2004 Abstract The primaryaim of this thesisis to assessvertical integration in the UK aerospace industrywith a transactioncost approach. There is an extensivetheoretical and conceptualliterature on transactioncosts, but a relativelack of empiricalwork. This thesisapplies transaction cost economics to the UK aerospaceindustry focusing on the paradigmproblem of the make-or-buydecision and related contract design. It assesses whetherthe transactioncost approachis supported(or rejected)by evidencefrom an originalsurvey of theUK aerospaceindustry. The centralhypothesis is that UK aerospacefirms are likely to makecomponents in- housedue to higherlevels of assetspecificity, uncertainty, complexity, frequency and smallnumbers, which is reflectedin contractdesign. The thesismakes these concepts operational.The empiricalmethodology of the thesisis basedon questionnairesurvey dataand econometric tests using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) andlogit regressions to analysethe make-or-buy decision and the choiceof contracttype. The resultsfrom this thesisfind limited evidencein supportof the transactioncost approachapplied to the UK aerospaceindustry, in spiteof a bespokedataset. The empiricaltests of verticalintegration for both make-or-buyand contracttype as the dependentvariable yield insufficientevidence to concludethat the transactioncost approachis an appropriateframework -

2 South Pacific Aviation Safety Management Systems Symposium

2nd South Pacific Aviation Safety Management Systems Symposium Queenstown, 17 th /18 th Feb 2010 Symposium Programme compiled, designed and sponsored by , , 2nd South Pacific Aviation `Safety Management Systems’ Symposium – Queenstown, 17 th /18 th Feb 2010 SMS Implementation and Metrics “How do you do it , and how do you measure it” DAY ONE (17 th Feb 2010) Times Activity / Presentation Speaker 10.00-10.30 Registrations and Morning Tea - Sponsored by Queenstown Airport 10.30-10.40 • Call together Capt Bryan Wyness • Welcome on behalf of AIA Irene King • Welcome on behalf of CAANZ Graeme Harris 10.40-11.05 • GAPAN welcome Capt Wyness • Summaries and Reflectives from the first Symposium (getting on the same page) • Symposium Themes and format SMS Progress Reports: our `systems of safety’ of `systems our our `systems of safety’ of `systems our our `systems of safety’ of safety’ `systems of our `systems our • SAC/IRM Committees Ashok Poduval • ACAG and PWG (Project Working Group) Qwilton Biel • CAANZ Simon Clegg 11.05-11.45 • “The challenges of SMS implementation Dr Rob Lee and integration - some practical guidance” 11.45-12.10 • “A look at the new AS/NZS31000 - Geraint Birmingham implications and insights for the development of SMS’s” 12.10-12.20 • Questions From Delegates 12.20-12.50 Lunch – Sponsored by Navigatus Risk Consulting 12.50-12.55 Brief on the first workshop – format and Neil Airey outcome, 12.55-13.25 Workshop #1 1. Identify Top 10 issues within each 1. Odd Numbered Groups Certificate (Airline, GA, Airport, Airways How are we integrating, operating and implementing implementing and operating integrating, we are How How are we integrating, operating and implementing implementing and operating integrating, we are How How are we integrating, operating and implementing implementing and operating integrating, we are How How are we integrating, operating and implementing implementing and operating integrating, we are How and Maintenance), 2. -

Defence White Paper 2003

House of Commons Defence Committee Defence White Paper 2003 Fifth Report of Session 2003–04 Volume I HC 465-I House of Commons Defence Committee Defence White Paper 2003 Fifth Report of Session 2003–04 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 23 June 2004 HC 465-I Published on 1 July 2004 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Defence Committee The Defence Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Defence and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr Bruce George MP (Labour, Walsall South) (Chairman) Mr Crispin Blunt MP (Conservative, Reigate) Mr James Cran MP (Conservative, Beverley and Holderness) Mr David Crausby MP (Labour, Bolton North East) Mike Gapes MP (Labour, Ilford South) Mr Mike Hancock CBE MP (Liberal Democrat, Portsmouth South) Dai Havard MP (Labour, Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney) Mr Kevan Jones MP (Labour, North Durham) Mr Frank Roy MP (Labour, Motherwell and Wishaw) Rachel Squire MP (Labour, Dunfermline West) Mr Peter Viggers MP (Conservative, Gosport) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/defence_committee.cfm A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Case Study BAE Systems Eurofighter Typhoon

Executive Summary Eurofighter Typhoon is the world’s most advanced swing-role combat aircraft. A highly agile aircraft, it is capable of ground-attack as well as air defence. With 620 aircraft on order, it is also the largest and most complex European military aviation project currently running. A collaboration between Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK, it is designed to meet air force requirements well into the 21st Century. Advanced electronics and state of the art onboard computers are critical to the Typhoon’s high performance and agility. These systems need to be safe, reliable and easily maintained over the estimated 25 year lifecycle of the aircraft. The Ada programming language was therefore the natural choice for Typhoon’s onboard computers. It provides a high-integrity, high-quality development environment with a well defined structure that is designed to produce highly reliable and maintainable real-time software. Typhoon is currently the largest European Ada project with over 500 developers working in the language. Tranche 1 of the project saw 1.5 million lines of code being created. BAE Systems is a key member of the Eurofighter consortium, responsible for a number of areas including the aircraft’s cockpit. As part of latest phase of the project (named “Tranche 2”) it needed a solution for host Ada compilation in the development of software for the Typhoon’s mission computers, as well as for desktop testing. BAE Systems selected GNAT Pro from AdaCore in 2002 for this mission-critical and safety-critical area of the project. AdaCore has been closely involved with the Ada language since its inception and was able to provide a combination of multi-language technology and world-leading support to BAE Systems. -

Australian Naval Aviation Museum Are Tangible Examples of Your Continuing Interest and Support

The Quarterly Journal of the Fleet Air Arm Association of Australia Volume 7 Number 2 April 1996 Published by the Fleet Air Ann Association of Australia Inc. - Print Post Approved - PP201494/00022 Editor: John Arnold-PO Box 662, NOWRA NSW 2541, Australia - Phone (044) 232014 - Fax (044) 232412 Slipstream - April 1996 - Page 2 FOREWORD by Rear Admiral Murray B Forrest AM RAN Assistant Chief of Naval Staff (Personnel) Although I have never really been closely associated with the Fleet Air Arm, I do remember a rather daunting day or two at sea in MELBOURNE as a Cadet and several great Gunroom and Wardroom parties; looking through back numbers of your very spirited and entertaining magazine also reminds me of some wonderful people of my youth; and I do have many friends among your number . But that said, we are all a part of the same very fine Service and as Navy's current 'people' person, I am delighted to come to the party. Professionally, my early dealings with Naval Aviation were confined to the not so glamorous world of logistics where I was amazed by the staggering quantities of bits and pieces demanded by Air Engineers to keep those airframes flying and also gained an understanding of their commitment to air worthiness. The ROE [role of effort] has not diminished! Now, I have to man the aircraft and provide the technicians; not always an easy task but, as ever, there are many fine people in the Naval Personnel Division and the wider community to assist. In that role, the excellent contribution of the Fleet Air Arm Association in maintaining the esprit de corp is invaluable. -

Knights Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath

WESTMINSTER ABBEY ORDER OF SERVICE AND CEREMONY OF THE OATH AND INSTALLATION OF KNIGHTS GRAND CROSS OF THE MOST HONOURABLE ORDER OF THE BATH IN THE LADY CHAPEL OF KING HENRY VII THE CHAPEL OF THE ORDER IN THE ORDER’S 293 rd YEAR 11.15 am THURS DAY 24 th MAY 2018 THE INSTALLATION CEREMONY Although the Order of the Bath as we Even this fell into abeyance after know it today was created by Letters 1812, because of the enlargement of Patent passed under the Great Seal on the Order in 1815, and the installation 18 th May 1725, the origins of the ceremony was formally abolished in ceremony, which takes place in the 1847. It was revived in 1913 in the Henry VII Chapel, can be traced back modified form which continues in use to the 14 th century. A pamphlet of that to the present. Today the Knights are time refers to Knights receiving ‘a installed as a group and do not Degree of Knighthood by the Bath’ actually occupy their own stalls and describes part of the knighting during the installation. ceremony thus: The offering of gold and silver ‘The Knight shall be led into the represents partly a surrendering of Chapel with melody and there he worldly treasure and partly a shall un-girt him and shall offer his recognition by the new Knight of his sword to God and Holy Church to be duty to provide for the maintenance laid upon the Altar by the Bishop’. of Christ’s Church on earth. In today’s ceremony, the gold is represented by The original installation ceremony two sovereigns: 1895 with the head of was based largely on that used at the Queen Victoria and 1967 with the Coronation of Henry V on 9 th April head of Queen Elizabeth II. -

Makes for Luke

Royal Australian' T he official newspaper of the Royal Australian Navy Navy News. Locked Bag 12. Pyrmonl 2009 Aegistere<l by Australia Post Publication VOLUME 40, No. 11 Phone: (02) 9563 1202FIDC:(02) 9563 1411 June 16, 1997 AdvenisingPtlone:(02) 95631539 Fax (02)95631 411 No. VBH8876 Visit makes a grin• for Luke H~~~rt~ : d of H ~~0X'; NEWCASTLE when she visited her hom e por t of Ne"'castle after an 18 month absence. First of the visitors were 40 young people from the Hunter Orthopaed ic School, a do pted by the ship 's complement as its fal'ourUe charity. Aged from 10 to 16 years and wit h many confi ned to. wheelchairs, t he children's visit provid ed a busy time for LEUT Karen Rockmann and ABET Carolyn Denford and their helpers. NEW CASTLE wit h her The student's inspection of the ship got underway in the a fternoon , wilh a cockta il party on the helideck. Saturday and Sunday saw public inspection of the ship with NEWCASTLE putting to sea on Monday, June 2, for d rill in the eastern area training zone. "' we h ad not been to Newcastle for 18 months," SHLT Belinda Wood , the ship's liaison of1i ce r, said. " It was ver y s uccessful visil 10 our ' home' pori," she Old enemies• mourn • boffin LEUT Rob Gr.lOt In peace from NSCHQ 31 Pyrmont .... 3) only A torpedo all aek .... as H~~~1 f(lrt';~/I ' :; goe~ s mg. bUI u"s e1ther I~;~:: ah:~:e b~Ct~~ni~ launched on the USS Cou~lf, 1'lIIain, meon· a bug lh:1I stops the ing of th e depot ship CHI CAGO but failed 10 /~ur.