Folk Revivals: the UK and USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk for Art's Sake: English Folk Music in the Mainstream Milieu

Volume 4 (2009) ISSN 1751-7788 Folk for Art’s Sake: English Folk Music in the Mainstream Milieu Simon Keegan-Phipps University of Sheffield The English folk arts are currently undergoing a considerable resurgence; 1 practices of folk music, dance and drama that explicitly identify themselves as English are the subjects of increasing public interest throughout England. The past five years have seen a manifold increase in the number of professional musical acts that foreground their Englishness; for the first time since the last 'revival period' of the 1950s and 60s, it is easier for folk music agents to secure bookings for these English acts in England than Scottish and Irish (Celtic) bands. Folk festivals in England are experiencing greatly increased popularity, and the profile of the genre has also grown substantially beyond the boundaries of the conventional 'folk scene' contexts: Seth Lakeman received a Mercury Music Awards nomination in 2006 for his album Kitty Jay; Jim Moray supported Will Young’s 2003 UK tour, and his album Sweet England appeared in the Independent’s ‘Cult Classics’ series in 2007; in 2003, the morris side Dogrose Morris appeared on the popular television music show Later with Jools Holland, accompanied by the high-profile fiddler, Eliza Carthy;1 and all-star festival-headliners Bellowhead appeared on the same show in 2006.2 However, the expansion in the profile and presence of English folk music has 2 not been confined to the realms of vernacular, popular culture: On 20 July 2008, BBC Radio 3 hosted the BBC Proms -

Charles Parker, Documentary Performance, and the Search for a Popular Culture

David Watt ‘The Maker and the Tool’: Charles Parker, Documentary Performance, and the Search for a Popular Culture Charles Parker’s BBC Radio Ballads of the late 1950s and early 1960s, acknowledged by Derek Paget in NTQ 12 (November 1987) as a formative influence on the emergence of what he called ‘Verbatim Theatre’, have been given a new lease of life following their recent release by Topic Records; but his theatrical experiments in multi-media documentary, which he envisaged as a model for ‘engendering direct creativity in the common people’, remain largely unknown. The most ambitious of these – The Maker and the Tool, staged as part of the Centre 42 festivals of 1961–62 – is exemplary of the impulse to recreate a popular culture which preoccupied many of those involved in the Centre 42 venture. David Watt, who teaches Drama at the University of Newcastle, New South Wales, began researching these experiments with work on a case study of Banner Theatre of Actuality, the company Parker co-founded in 1973, for Workers’ Playtime: Theatre and the Labour Movement since 1970, co-authored with Alan Filewod. This led to further research in the Charles Parker Archive at Birmingham Central Library, and the author is grateful to the Charles Parker Archive Trust and the staff of the Birmingham City Archives (particularly Fiona Tait) for the opportunity to explore its holdings and draw on them for this article. IN JANUARY 1963 an amateur theatre group The Maker and the Tool, a ‘Theatre Folk Ballad’ in Birmingham, the Leaveners, held its first written/compiled and directed by Charles annual general meeting and moved accep- Parker and staged in a range of non-theatre tance of the following statement of aims: spaces in six different versions, one for each of the festival towns. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) • The

Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) The Rolling Stones – Grrr (Album Vinyl Box) Insane Clown Posse – Insane Clown Posse & Twiztid's American Psycho Tour Documentary (DVD) New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!! And more… UNI13-03 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Hollywood Undead – Notes From The Underground Bar Code: Cat. #: B001797702 Price Code: SP Order Due: December 20, 2012 Release Date: January 8, 2013 File: Hip Hop /Rock Genre Code: 34/37 Box Lot: 25 SHORT SELL CYCLE Key Tracks: We Are KEY POINTS: 14 BRAND NEW TRACKS Hollywood Undead have sold over 83,000 albums in Canada HEAVY outdoor, radio and online campaign First single “We Are” video is expected mid December 2013 Tour in the works 2.8 million Facebook friends and 166,000 Twitter followers Also Available American Tragedy (2011) ‐ B001527502 Swan Song (2008) ‐ B001133102 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Territory: Choose Release Type: Choose For additional artist information please contact JP Boucher at 416‐718‐4113 or [email protected]. UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Regular CD) Cat. #: B001781702 Price Code: SP 02537 22095 Order Due: Dec. 20, 2012 Release Date: Jan. 8, 2013 6 3 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 Short Sell Cycle Key Tracks: Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Deluxe CD/DVD) Cat. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

14302 76969 1 1>

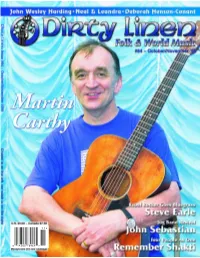

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Topic Records 80Th Anniversary Start Time: 8Pm Running Time: 2 Hours 40 Minutes with Interval

Topic Records 80th Anniversary Start time: 8pm Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston discusses the history behind the world’s oldest independent label ahead of this collaborative performance. When Topic Records made its debut in 1939 with Paddy Ryan’s ‘The Man That Waters The Workers’ Beer’, an accordion-backed diatribe against capitalist businessmen who underpay their employees, it’s unlikely that anyone involved was thinking of the future – certainly not to 2019, when the label celebrates its 80th birthday. In any case, the future would have seemed very precarious in 1939, given the outbreak of World War II, during which Topic ceased most activity (shellac was particularly hard to source). But post-1945, the label made good on its original brief: ‘To use popular music to educate and inform and improve the lot of the working man,’ explains David Suff, the current spearhead of the world’s oldest independent label – and the undisputed home of British folk music. Tonight at the Barbican (where Topic held their 60th birthday concerts), musical director Eliza Carthy – part of the Topic recording family since 1997, though her parents Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy have been members since the sixties and seventies respectively - has marshalled a line-up to reflect the passing decades, which hasn’t been without its problems. ‘We have far too much material, given it’s meant to be a two-hour show!’ she says. ‘It’s impossible to represent 80 years – you’re talking about the left-wing leg, the archival leg, the many different facets of society - not just communists but farmers and factory workers - and the folk scene in the Fifties, the Sixties, the Seventies.. -

M06 Ymateb Gan Traddodiadau Cerdd Cymru / Response from Music Traditions Wales

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Diwydiant Cerddoriaeth yng Nghymru / Music Industry in Wales CWLC M06 Ymateb gan Traddodiadau Cerdd Cymru / Response from Music Traditions Wales How do local authority decisions such as business rates, licensing and planning decisions impact upon live music venues? 1. There is very little that Local authorities can do to promote live music venues unless the council has a live music strategy in place. Without the political directive to recognise and value the local music scene local authorities do not see either their social or economic value and therefore do not take measures to preserve them as part of the Authority’s Plan. 2. It’s possible for a local authority to be imaginative, use Planning Gain to require developers to support live music as a “public art”, make measurable provision of live music a condition of renewing and awarding licences but this needs leadership. 3. In our experience, a local authority’s staff, with one or two exceptions do not know how to recognise the value of a live music venue. The social benefits do not fit into their metrics. Very often a policy that seeks to attract inward investment discounts the value of small businesses. 4. Most live music in Wales does not happen in dedicated venues and theatres. It happens in bars & pubs, social clubs, meantime & pop-up spaces, fields, weddings, festivals. It is frequently a valuable part of a business for the retention of customers etc, but rarely forms the main part of a business’ revenue. -

Warwickshire Cover

Worcestershire Cover Online.qxp_Birmingham Cover 29/07/2016 10:58 Page 1 Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands ISSUE 368 AUGUST 2016 JIMMY OSMOND Worcestershire OUT ON NEW UK TOUR ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On worcestershirewhatson.co.uk inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide PRESENT LAUGHTER NOËL COWARD’S COMEDY ARRIVES AT MALVERN THEATRES Donington F/P - August '16.qxp_Layout 1 25/07/2016 10:08 Page 1 Contents August Warwickshire/Worcs.qxp_Layout 1 25/07/2016 12:09 Page 1 August 2016 Contents The Rover - Aphra Behn’s play returns to the Swan Theatre. Feature page 8 Julian Marley Sir Antony Sher Spectacular Science the list Reggae superstar embarks on Award-winning actor takes on Brand new show to dispel Your 16-page his first ever UK tour King Lear at the RSC ‘science is boring’ myth... week-by-week listings guide page 14 page 30 page 26 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 14. Music 26. Comedy 28. Theatre 37. Film 40. Visual Arts 43. Events fb.com/whatsonwarwickshire fb.com/whatsonworcestershire @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Managing Director: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Matt Rothwell [email protected] 01743 281719 Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Whats On Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 MAGAZINE GROUP Editorial: Lauren Foster [email protected] -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

The Watersons the Definitive Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Watersons The Definitive Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: The Definitive Collection Country: UK Released: 2003 Style: Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1203 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1609 mb WMA version RAR size: 1410 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 881 Other Formats: AHX AUD MP4 AU MP1 MMF DTS Tracklist 1 God Bless The Master 3:05 2 Dido Bendigo 2:53 3 The Welcome Sailor 3:12 4 Emmanuel 2:48 5 Idumea 1:48 6 The Still And Silent Ocean 4:25 7 Fathom The Bowl 2:52 8 Fare Thee Well Cold Winter 2:32 9 The Holmfirth Anthem 1:58 10 Stormy Winds 3:10 11 Rosebuds In June 3:15 12 Bellman 3:55 13 Sleep On Beloved 3:03 14 Swansea Town 4:18 15 The Beggar Man 3:26 16 Amazing Grace 4:38 17 The Old Churchyard 3:23 18 Adieu Sweet Lovely Nancy 3:38 19 Malpas Wassail 4:11 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Topic Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Topic Records Ltd. Licensed From – Topic Records Ltd. Published By – Concorde International Management Consultants Ltd. Published By – Gwyneth Music Ltd. Published By – Topic Records Ltd. Published By – MCS Music Limited Published By – Free Reed Music Published By – April Music Ltd. Published By – Mole Music Ltd Credits Accompanied By – Gabriel's Horns (tracks: 4) Concertina [Anglo-concertina] – Tony Engle (tracks: 15) Fiddle – Peta Webb (tracks: 15) Guitar – Martin Carthy Melodeon – Rod Stradling (tracks: 15) Performer – Anthea Bellamy (tracks: 16), Barry Coope (tracks: 18), Blue Murder (tracks: 18), Eliza Carthy (tracks: 13, 17, 18), Jim Boyes (tracks: 18), Jim -

Sarah Morgan

Context statement – Sarah Morgan Community Choirs – A Musical Transformation A review of my work in management, music, choir leadership and folk-song. The University of Winchester Faculty of Arts Submitted by Sarah Morgan to the University of Winchester The context statement for the degree of Professional Doctorate by Contribution to Public Work This context statement has been completed as a requirement for a Post-Graduate Research Degree of the University of Winchester. The word count in this document is 39, 933. This context statement is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this statement may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this context statement which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. In accordance with the customs and norms of the host institution, it has not been possible in this work to anonymise organisations. 1 Context statement – Sarah Morgan University of Winchester Abstract for context statement: Community Choirs – A Musical Transformation A review of my work in management, music, choir leadership and folk-song. Sarah Margaret Morgan Faculty of Arts Professional Doctorate by Contribution to Public Work Submission date September 2013 2 Context statement – Sarah Morgan Abstract: My aims have always been to present an exploration of English community choirs, their music and their leadership from a very personal perspective, which brings together my background as a folk musician, my career in training and facilitation, and my developing understanding of a system of musical hierarchies which (though often unspoken) inform and colour not only my own musical experience but that of many others.