41 OFF the LINE Expanding Creativity in the Production and Distribution of Web Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Move Over, Amateurs

Web Video: Move Over, Amateurs As more professionally produced content finds a home online, user- generated video becomes less alluring to viewers—and advertisers by Catherine Holahan November 20, 2007 Amateur filmmakers hoping to win fame for amusing moments captured on camcorder ought to stick to TV's long-running America's Funniest Home Videos. These days they're not getting much love on the Web. One after another, online video sites that have long showcased such fare as skateboarding dogs and beer-drenched parties are scaling back their focus on user- generated clips, often in favor of professionally produced programming. "People would rather watch content that has production value than watch their neighbors in the garage," says Matt Sanchez, co-founder and chief executive of VideoEgg, a company that provides Web video tools, ads, and advertising features for online video providers and Web application developers. On Nov. 13 social networking site Bebo said it would open its pages to top media companies in hopes of luring and engaging viewers. "As more and more interesting content from major media brands becomes available, [online viewers] are going to share that more and more because those are the brands they identify with," says Bebo President Joanna Shields. Another site, ManiaTV, recently canceled its user-generated channels altogether (BusinessWeek.com, 10/22/07). The 3,000 user-generated channels simply didn't pull in enough viewers, ManiaTV CEO Peter Hoskins says. Roughly 80% of people were watching the professional content produced by celebrities such as musician Dave Navarro and comedian Tom Green. "What we found out is, we don't need the classical user-generated talent when we have the Hollywood talent that wants to Coverage secured by Kel & Partners www.kelandpartners.com work with us," Hoskins says. -

Shon Hedges Editor

SHON HEDGES EDITOR FEATURES iGILBERT Paloma Pictures Prod: Cynthia Hargrave, Adrian Martinez Dir: Adrian Martinez Anthony Vorhies PICTURE PARIS (Short) For Goodness Sake Prod: Brad Hall, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Julie Snyder Dir: Brad Hall *Official Selection, Tribeca Film Festival, 2012 GENEROSITY OF EYE (Documentary) For Goodness Sake Prod: Brad Hall, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Julie Snyder Dir: Brad Hall ABOUT SUNNY (Associate Editor) On the Line Prods./ Prod: Lauren Ambrose, Blythe Robertson, Mike Ryan Dir: Bryan Wizemann Votiv Films AFRICAN ADVENTURE: nWave Pictures Prod: Ben Stassen Dir: Ben Stassen SAFARI IN THE OKAVANGO (Documentary) TELEVISION NEW AMSTERDAM (Season 1) Universal/NBC Prod: Peter Horton, David Schulner Dir: Various THE ORVILLE (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/Fox Prod: Seth McFarlane, David Goodman Dir: Various Brannon Braga, John Cassar BULL (Season 1) CBS Studios/CBS Prod: Mark Goffman, Paul Attanasio Dir: Various BLACK SAILS (Ep. 106, 209, 302) Starz Prod: Michael Bay, Jonathan Steinberg, Dan Shotz Dir: T.J. Scott, Lukas Ettlin HEROES REBORN (Season 1) Universal/NBC Prod: Tim Kring, Lori Motyer Dir: Various HOMELAND (Season 2) Fox 21/Showtime Prod: Alex Gansa, Meredith Stiehm, Howard Gordon Dir: Various (Additional Editing) THE KILLING (Season 2) Fox TV/AMC/Netflix Prod: Veena Sud, Mikkel Bondesen, Ron French Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) SMASH (Pilot) (Assistant Editor) Universal/NBC Prod: Justin Falvey, Darryl Frank, Marc Shaiman Dir: Michael Mayer IN PLAIN SIGHT (Ep. 403) USA Prod: David Maples Dir: Michael Schultz (Assistant Editor) IN TREATMENT (Ep. 326, 327, 328) HBO Prod: Paris Barclay, Anya Epstein Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) RUBICON (Season 1) Warner Horizon/AMC Prod: Henry Bromwell, Jason Horwitch Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) A MARRIAGE (Pilot) CBS Prod: Ed Zwick, Marshall Herzkovitz Dir: Marshall Herskovitz QUARTERLIFE (3 episodes) NBC Prod: Ed Zwick, Marshall Herzkovitz Dir: Marshall Herskovitz, Catherine Jelski 405 S Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California 90212 - T 310.888.4200 - F 310.888.4242 www.apa-agency.com . -

From the Bedroom to LA: Revisiting the Settings of Early Video Blogs on Youtube 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Rainer Hillrichs From the bedroom to LA: Revisiting the settings of early video blogs on YouTube 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3359 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Hillrichs, Rainer: From the bedroom to LA: Revisiting the settings of early video blogs on YouTube. In: NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, Jg. 5 (2016), Nr. 2, S. 107–131. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3359. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://www.necsus-ejms.org/test/from-the-bedroom-to-la-revisiting-the-settings-of-early-video-blogs-on-youtube/ Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org From the bedroom to LA: Revisiting the settings of early video blogs on YouTube Rainer Hillrichs NECSUS 5 (2), Autumn 2016: 107–131 URL: https://necsus-ejms.org/from-the-bedroom-to-la-revisiting- the-settings-of-early-video-blogs-on-youtube/ Keywords: audiovisual media, digital culture, genre, home, online video, Web 2.0 The home is only one of many settings in contemporary YouTube videos. On professionalised video blogs, domestic settings are only used when they are motivated by particular video projects. -

TSC Resume-Current for Website-Sheet1

FEATURE FILMS (CONDENSED LIST): OFFICE CHRISTMAS PAETY DreamWorks Pictures GUARDIANS of the GALAXY Vol. 2 Marvel Studios SULLY Warner Bros. GIFTED Fox Searchlight Pictures MIRACLES FROM HEAVEN SONY Pictures Entertainment CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR Marvel Studios IN DUBIOUS BATTLE Rabbit Bandini Productions THE 5th WAVE SONY Pictures Entertainment THE NICE GUYS Warner Bros. VACATION New Line Cinema TAKEN 3 20th Century Fox GET ON UP Universal Pictures BARELY LETHAL RKO Pictures BLENDED Universal Pictures ENDLESS LOVE Universal Pictures THE HOMESMAN Briggs & Cuddy Inc. NEED FOR SPEED DreamWorks Pictures PRISONERS Alcon Entertainment THE LAST OF ROBIN HOOD Killer Films IDENTITY THIEF Universal Pictures * THE DARK KNIGHT RISES Warner Bros * A BETTER LIFE Summit Entertainment !1 * I LOVE YOU, MAN DreamWorks * GOOD NIGHT AND GOOD LUCK Warner Independent Pictures * DREAMGIRLS DreamWorks Pictures * EVAN ALMIGHTY Universal Pictures * 17 AGAIN New Line Cinema * G-FORCE Walt Disney Pictures * RAY Universal Pictures * ROLE MODELS Universal Pictures * SUPERHERO MOVIE MGM * I COULD NEVER BE YOUR WOMAN Scott Rudin Productions * THE HEARTBREAK KID DreamWorks Pictures * SMOKIN' ACES Universal Pictures * FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION Warner Bros. * SCHOOL FOR SCOUNDRELS MGM * FUN WITH DICK AND JANE Columbia Pictures * MEET THE FOCKERS Universal Pictures * BRUCE ALMIGHTY Universal Pictures * KICKING AND SCREAMING Universal Pictures * ART SCHOOL CONFIDENTIAL SONY Pictures Classics * BE COOL MGM * ALONG CAME POLLY Universal Pictures * DRAGONFLY Universal Pictures * CHRISTMAS WITH THE KRANKS Columbia Pictures * Co-OWNER and Casting Director - SMITH & WEBSTER-DAVIS CASTING - 2/1999 thru 2/2012 !2 * FAT ALBERT 20TH Century Fox * BIKER BOYZ DreamWorks Pictures * BRINGING DOWN THE HOUSE Disney (Touchstone) * SURVIVING CHRISTMAS DreamWorks Pictures * SIDEWAYS Fox Searchlight Pictures * COYOTE UGLY Disney(Touchstone) * THIRTEEN DAYS New Line Cinema * THE WHOLE 10 YARDS Warner Bros. -

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21 Classified, Page 26 Classified, ❖ ABC News Reporter Jennifer Donelan, a native of Fairfax County, gave the keynote address for the June 17 Lake Braddock Secondary Commencement. Donelan could not emphasize enough that this moment is a Real Estate, Page 16 Real Estate, ❖ milestone and a stepping off point to the future. Camps & Schools, Page 11 Camps & Schools, ❖ Faith, Page 23 ❖ Sports, Page 24 insideinside Requested in home 6-20-08 Time sensitive material. Attention Postmaster: U.S. Postage Word Out PRSRT STD PERMIT #322 Easton, MD On Repairs Koger Firm PAID News, Page 3 Auctioned Off News, Page 3 Photo By Louise Krafft/The Connection By Louise Krafft/The Photo www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com June 19-25, 2008 Volume XXII, Number 25 Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Burke Connection Editor Michael O’Connell News 703-917-6440 or [email protected] 2 Cases, 2 Courts, Same Day Groner gave Koger his Jeffrey Koger appears in Miranda rights en route to court on attempted capital Inova Fairfax Hospital. “You are under arrest for murder of police officer. attempted capital murder Koger Firm Sold of a police officer,” Groner told Koger, who was admit- Sheriff’s Photo Sheriff’s By Ken Moore ted to the hospital in criti- Troubled management firm The Connection cal condition. On Tuesday, June 17, auctioned in bankruptcy court. effrey Scott Koger held a shotgun Judge Penney S. Azcarate against his shoulder and pointed the certified the case to a By Nicholas M. -

Download Spring 2010

2010SpringSummer_Cover:Winter05Cover 11/11/09 11:24 AM Page 1 NATHALIE ABI-EZZI SHERMAN ALEXIE RAFAEL ALVAREZ JESSICA ANTHONY NICHOLSON BAKER CHARLES BEAUCLERK SAMUEL BECKETT G ROVE P RESS CHRISTOPHER R. BEHA THOMAS BELLER MARK BOWDEN RICHARD FLANAGAN HORTON FOOTE ATLANTIC M ONTHLY PRESS JOHN FREEMAN JAMES HANNAHAM TATJANA HAUPTMANN ELIZABETH HAWES SHERI HOLMAN MARY-BETH HUGHES B LACK CAT DAVE JAMIESON ISMAIL KADARE LILY KING DAVID KINNEY MICHAEL KNIGHT G RANTA AND O PEN C ITY DAVID LAWDAY lyP MIKE LAWSON nth r JEFF LEEN o es DONNA LEON A A A A M s ED MACY t t t t c KARL MARLANTES l l l l ti NICK MC DONELL n TERRY MC DONELL a CHRISTOPHER G. MOORE JULIET NICOLSON SOFI OKSANEN P. J. O’ ROURKE ROBERTA PIANARO JOSÉ MANUEL PRIETO PHILIP PULLMAN ROBERT SABBAG MARK HASKELL SMITH MARTIN SOLARES MARGARET VISSER GAVIN WEIGHTMAN JOSH WEIL TOMMY WIERINGA G. WILLOW WILSON ILYON WOO JOANNA YAS ISBN 978-1-55584-958-0 ISBN 1-55584-958-X GROVE/ATLANTIC, INC. 50000 841 BROADWAY NEW YORK, NY 10003 9 781555 849580 ATLANTIC MONTHLY PRESS HARDCOVERS APRIL This novel, written by a Marine veteran over the course of thirty years, is a remarkable literary discovery: a big, powerful, timeless saga of men in combat MATTERHORN A Novel of the Vietnam War Karl Marlantes PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR • Marlantes is a graduate of Yale University and a Rhodes Scholar who went on to serve as a Marine “Matterhorn is one of the most powerful and moving novels about combat, lieutenant in Vietnam, where he the Vietnam War, and war in general that I have ever read.” —Dan Rather was highly decorated ntense, powerful, and compelling, Matterhorn is an epic war novel in the • Matterhorn will be copublished tradition of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’s with El León Literary Arts IThe Thin Red Line. -

Introduction

MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching Vol. 5, No. 2, June 2009 Integrating Online Multimedia into College Course and Classroom: With Application to the Social Sciences Michael V. Miller Department of Sociology The University of Texas at San Antonio San Antonio, TX 78249 USA [email protected] Abstract Description centers on an approach for efficiently incorporating online media resources into course and classroom. Consideration is given to pedagogical rationale, types of media, locating programs and clips, content retrieval and delivery, copyright issues, and typical problems experienced by instructors and students using online resources. In addition, selected media-relevant websites appropriate to the social sciences along with samples of digital materials gleaned from these sites are listed and discussed. Keywords: video, audio, media, syllabus, documentaries, Internet, YouTube, PBS Introduction Multimedia resources can markedly augment learning content by virtue of generating vivid and complex mental imagery. Indeed, instruction dependent on voice lecture and reading assignments alone often produces an overly abstract treatment of subject matter, making course concepts difficult to understand, especially for those most inclined toward concrete thinking. Multimedia can provide compelling, tangible applications that help breakdown classroom walls and expose students to the external world. It can also enhance learning comprehension by employing mixes of sights and sounds that appeal to variable learning styles and preferences. Quality materials, in all, can help enliven a class by making subject matter more relevant, experiential, and ultimately, more intellectually accessible. Until recently, nonetheless, film and other forms of media were difficult to exploit. They had to be located, ordered, and physically procured well in advance either through purchase, library loan, or broadcast dubbing. -

The Evolution of New Media

GREEN HASSON JANKS | FALL 2016 ENTERTAINMENT REPORT THE EVOLUTION OF NEW MEDIA MAKING MONEY IN A WORLD WHERE DIGITAL STREAMING RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME LETTER FROM GREEN HASSON JANKS 03 ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA PRACTICE LEADER 04 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 06 SURVEY HIGHLIGHTS 08 INDUSTRY EXPERTS 09 GREEN HASSON JANKS EXPERTS 10 GLOBALIZATION 16 MONETIZATION LOOKING TO 26 THE FUTURE 31 ABOUT THE SURVEY RESPONDENTS 32 KEY TAKEAWAYS 36 ABOUT GREEN HASSON JANKS AUTHORS 38 ABOUT GREEN HASSON JANKS CONTRIBUTORS 41 ABOUT THE SUBJECT MATTER EXPERTS 2 WELCOME The entertainment and media industry is moving quickly, driven by technology and industry disrupters. We cannot predict the future, but we have assembled a stellar group of industry experts to share their knowledge and expectations on the topic of monetization and globalization. I am proud of my team’s authorship of our 4th annual whitepaper, and found it to be an important read on where we are heading as an industry and as a profession. I hope you will also find this whitepaper informative and thought provoking – it is part of our continuing efforts to provide value to the entertainment community. If you have ideas, feedback or your own story to share, please do not hesitate to contact me. Ilan Haimoff Partner and Entertainment and Media Practice Leader, Green Hasson Janks [email protected] 310.873.1651 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Streaming services have emerged as significant disrupters in the entertainment industry. With this in mind, the Green Hasson Janks 2016 Entertainment and Media Survey and industry expert interviews focused on global distribution rights and monetization within the context of a world where video streaming services are growing exponentially. -

Big Dreams, Small Screens: Online Video for Public Knowledge and Action

March 2007 BIG DREAMS, SMALL SCREENS: Online Video for Public Knowledge and Action By Jessica Clark A Future of Public Media Project Funded by the Ford Foundation centerforsocialmedia.org The Center for Social Media showcases and analyzes media for public knowledge and action. Directed by Prof. Pat Aufderheide, it is part of American University’s School of Communication, which is headed by Dean Larry Kirkman. The Future of Public Media Project, funded by the Ford Foundation, explores the strategies and technologies that are enabling tomorrow’s public media. Jessica Clark is a research fellow at the Center for Social Media and an editor at large at In These Times magazine. She holds an MA in social sciences from the University of Chicago and has been researching and writing about technology, media, and public issues since the early ’90s. For a PDF version of this report, for more center reports and publications, or for more information, go to centerforsocialmedia.org. BIG DREAMS, SMALL SCREENS: ONLINE VIDEO FOR PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE AND ACTION By Jessica Clark Funded by the Ford Foundation EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This study describes ways in which users are employing popular commercial online digital video platforms, such as YouTube, GoogleVideo, and MySpace, to create, exchange, and comment upon information for public knowledge and action. These new platforms provide a site to test the proposition that new publics are being created around open media spaces on the Internet. These emerging video sites are enormously popular, potentially attracting -

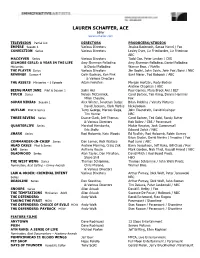

LAUREN SCHAFFER, ACE Editor Laurenschaffer.Com

LAUREN SCHAFFER, ACE Editor laurenschaffer.com TELEVISION Partial List DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS EMPIRE Season 4 Various Directors Jessica Badenoch, Sanaa Hamri / Fox CONVICTION Series Various Directors Lesley Dyer, Liz Friedlander, Liz Friedman ABC MACGYVER Series Various Directors Todd Coe, Peter Lenkov / CBS GILMORE GIRLS: A YEAR IN THE LIFE Amy Sherman-Palladino Amy Sherman-Palladino, Daniel Palladino Miniseries & Daniel Palladino Warner Bros. / Netflix THE PLAYER Series Various Directors Jim Sodini, John Davis, John Fox /Sony / NBC REVENGE Season 4 Colin Bucksey, Ken Fink Sunil Nayar, Ted Babcock / ABC & Various Directors THE ASSETS Miniseries – 1 Episode Adam Feinstein Morgan Hertzan, Rudy Bednar Andrew Chapman / ABC BEING MARY JANE Pilot & Season 1 Salim Akil Paul Garnes, Mara Brock Akil / BET TOUCH Series Nelson McCormick, Carol Barbee, Tim Kring, Dennis Hammer Milan Cheylov, Fox SUPAH NINJAS Season 1 Alex Winter, Jonathan Judge Br ian Robbins / Varsity Pictures David Jackson, Clark Mathis Nickelodeon OUTLAW Pilot & Series Terry George, Marcos Siega, John Eisendrath, David Kissinger Tim Hunter NBC THREE RIVERS Series Duane Clark, Jeff Thomas Carol Barbee, Ted Gold, Randy Sutter & Various Directors Rob Bailey / CBS / Paramount QUARTERLIFE Series Marshall Herskovitz, Mickie Reuster, Josh Gummersall Eric Stoltz Edward Zwick / NBC SHARK Series Rod Holcomb, Kate Woods Ed Redlich, Rod Holcomb, Robin Gurney Brian Grazer, David Nevins / Imagine / Fox COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF Series Dan Lerner, Rick Wallace Rod Lurie / ABC HEAD CASES Pilot & Series Andrew Fleming, Craig Zisk Barry Josephson, Jeff Rake, Bill Chais / Fox LAX Series Anthony Russo Mark Gordon, Nick Thiel, Russell Friend / NBC DEADWOOD Series Alan Taylor, Dan Minahan, David Milch / Red Board Prods. -

Download Magazine

UCLA LAW The Magazine of UCLA School of Law Box 951476 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1476 VOLUME 31 VOLUME | NUMBER 1 NOW IS UCLA THEUCLA SCHOOL TIME OF LAW ALUMNI AND FRIENDS LAW GIVING BACK AND BREAKING RECORDS! ASTOUNDING RESULTS IN 2008 FOR PRIVATE FUNDRAISING Thanks to momentum built up over the past few years for the $100 MILLION CAMPAIGN FOR UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW: UCLA Law closed biggest fundraising year ever in 2008 – BRINGING IN MORE THAN $30 MILLION IN PRIVATE SUPPORT FROM ALUMNI AND FRIENDS. UCLA Law has MORE THAN DOUBLED THE NUMBER OF ENDOWED CHAIRS to recruit and retain faculty. The ALUMNI PARTICIPATION RATE for alumni giving back has exploded – UP FROM 16 PERCENT F SIX YEARS AGO TO 31 PERCENT THIS YEAR! This puts UCLA Law alumni in the top five of all ALL 2008 American law schools for generosity in giving back. Law Firm Challenge leads the way in alumni giving. Number of firms reaches record-breaking 76 firms with 75 percent overall alumni giving participation rate. 32 FIRMS WORLDWIDE REACH EXTRAORDINARY 100 PERCENT ALUMNI GIVING. 205275_Cover_r3.indd 1 9/10/2008 11:06:17 AM 100% The worldwide community of UCLA School of Law alumni has rallied to provide its alma mater with unprecedented philanthropic support during the fiscal year that ended June 30. An astonishing 75 percent of alumni participating in the 2008 Law Firm Challenge made gifts to the school, with the firms listed here—27 of the 68 Challenge firms—achieving 100 percent participation in giving. GROUP I (30+ UCLA LAW ALUMNI) GROUP II (11-29 UCLA LAW ALUMNI) PARTICIPATION: 86% PARTICIPATION: 66% Cox Castle & Nicholson LLP - 34 alumni Christensen, Glaser, Fink, Jacobs, Weil UCLA LAW UCLA Law Board of Advisors UCLA Law Alumni Association Tamar C. -

Writing the Web Series ARONIVES

Byte-Sized TV: Writing the Web Series ARONIVES MASACHUSETTS INSTME By OF TECHNOLOGY Katherine Edgerton MAY 1 4 2013 B.A. Theatre and History, Williams College, 2008 LIBRARIES SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES/WRITING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2013 © Katherine Edgerton, All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: / /I - -11-11 Program in Comparative Media Studies/Writing May 10,2013 Certified by: Heather Hendershot Professor of Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Heather Hendershot Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director of Comparative Media Studies Graduate Program Byte-Sized TV: Writing the Web Series By Katherine Edgerton Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies/Writing on May 10, 2013 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT Web series or "webisodes" are a transitional storytelling form bridging the production practices of broadcast television and Internet video. Shorter than most television episodes and distributed on online platforms like YouTube, web series both draw on and deviate from traditional TV storytelling strategies. In this thesis, I compare the production and storytelling strategies of "derivative" web series based on broadcast television shows with "original" web series created for the Internet, focusing on the evolution of scripted entertainment content online.