Sixty Years in the Social-Democratic Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide These notes are designed to help new comrades to understand some of the basic ideas of Marxism and how they relate to the politics of the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty (AWL). More experienced comrades leading the educationals can use the tutor notes to expand on certain key ideas and to direct comrades to other reading. Paul Hampton September 2006 1 The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide Contents Background to the Manifesto 3 Questions 5 Further reading 6 Title, preface, preamble 7 I: Bourgeois and Proletarians 9 II: Proletarians and Communists 19 III: Socialist and Communist Literature 27 IV: Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties 32 Glossary 35 2 Background to the Manifesto The text Karl Marx wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party in German. It was first published in February 1848. It has sometimes been misdated 1847, including in Marx and Engels’ own writings, by Kautsky, Lenin and others. The standard English translation was done by Samuel Moore in 1888 and authorised by Frederick Engels. It can be downloaded from the Marxist Internet Archive http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/index.htm There are scores of other editions by different publishers and with other translations. Between 1848 and 1918, the Manifesto was published in more than 35 languages, in some 544 editions, (Beamish 1998 p.233) The text is also in the Marx and Engels Collected Works (MECW), Volume 6, along with other important articles, drafts and reports from the time. http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/cw/volume06/index.htm The context The Communist Manifesto was written for and published by the Communist League, an organisation founded less than a year before it was written. -

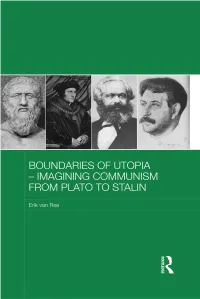

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin The idea that socialism could be established in a single country was adopted as an official doctrine by the Soviet Union in 1925, Stalin and Bukharin being the main formulators of the policy. Before this there had been much debate as to whether the only way to secure socialism would be as a result of socialist revolution on a much broader scale, across all Europe or wider still. This book traces the development of ideas about communist utopia from Plato onwards, paying particular attention to debates about universalist ideology versus the possibility for ‘socialism in one country’. The book argues that although the prevailing view is that ‘socialism in one country’ was a sharp break from a long tradition that tended to view socialism as only possible if universal, in fact the territorially confined socialist project had long roots, including in the writings of Marx and Engels. Erik van Ree is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series 1 Liberal Nationalism in 7 The Telengits of Central Europe Southern Siberia Stefan Auer Landscape, religion and knowledge in motion 2 Civil-Military Relations in Agnieszka Halemba Russia and Eastern Europe David J. Betz 8 The Development of Capitalism in Russia 3 The Extreme Nationalist Simon Clarke Threat in Russia The growing influence of 9 Russian Television Today Western Rightist ideas Primetime drama and comedy Thomas Parland -

Hörmann, Raphael (2007) Authoring the Revolution, 1819- 1848/49: Radical German and English Literature and the Shift from Political to Social Revolution

Hörmann, Raphael (2007) Authoring the revolution, 1819- 1848/49: radical German and English literature and the shift from political to social revolution. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1774/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] University of Glasgow Faculty of Arts PhD-Thesis in Comparative Literature Authoring the Revolution, 1819-1848/49: Radical German and English Literature and the Shift from Political to Social Revolution Submitted by Raphael HoUrmann @ Raphael H6nnann 2007 Acknowledgments I like to thank the various people and agenciesthat have provided vital help during various stages of this research project. First of all, I am greatly thankful to my supervisors, Professor Mark Ward and Dr. Laura Martin. Laura's pragmatic and practical advice and assistanceproved very helpful for overcomingall major obstacles in the course of my PhD studies at the University of Glasgow. Mark has not only been a tireless proof-reader at various stagesof the thesis, but his great enthusiasm with which he supported my project has been a continuous source of inspiration and encouragement throughout the writing and revising process. -

Karl Marx and the Iwma Revisited 299 Jürgen Herres

“Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” <UN> Studies in Global Social History Editor Marcel van der Linden (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Sven Beckert (Harvard University, Cambridge, ma, usa) Dirk Hoerder (University of Arizona, Phoenix, ar, usa) Chitra Joshi (Indraprastha College, Delhi University, India) Amarjit Kaur (University of New England, Armidale, Australia) Barbara Weinstein (New York University, New York, ny, usa) volume 29 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sgsh <UN> “Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” The First International in a Global Perspective Edited by Fabrice Bensimon Quentin Deluermoz Jeanne Moisand leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover illustration: Bannière de la Solidarité de Fayt (cover and back). Sources: Cornet Fidèle and Massart Théophile entries in Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier en Belgique en ligne : maitron-en -ligne.univ-paris1.fr. Copyright : Bibliothèque et Archives de l’IEV – Brussels. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bensimon, Fabrice, editor. | Deluermoz, Quentin, editor. | Moisand, Jeanne, 1978- editor. Title: “Arise ye wretched of the earth” : the First International in a global perspective / edited by Fabrice Bensimon, Quentin Deluermoz, Jeanne Moisand. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2018] | Series: Studies in global social history, issn 1874-6705 ; volume 29 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018002194 (print) | LCCN 2018004158 (ebook) | isbn 9789004335462 (E-book) | isbn 9789004335455 (hardback : alk. -

Marx and Engels and the Communist Movement the Following Article Is a Chapter from the Idea: Anarchist Communism, Past, Present and Future by Nick Heath

Marx and Engels and the Communist Movement The following article is a chapter from The Idea: Anarchist Communism, Past, Present and Future by Nick Heath. We should point out that whilst we regard Marx's analysis of capitalism and class society as a very important contribution to revolutionary ideas, we are critical of his attitudes and behaviour within both the Communist League and the First International. Marx was to re-iterate his ideas and to put them into practice in all his time in the working class movement. “Without parties no development, without division no progress” he was to write (polemic with the Kölnische Zeitung newspaper, 1842). In a much later letter to Bebel written in 1873, Engels sums up this approach: “For the rest, old Hegel has already said it; a party proves itself a victorious party by the fact that it splits and can stand the split. The movement of the proletariat necessarily passes through stages of development; at every stage one section of the people lags behind and does not join in the further advance; and this alone explains why it is that actually the “solidarity of the proletariat” is everywhere realised in different party groupings which carry on life and death feuds with one another”. The mythology of Marxism implies that the theory of communism was perfected by Marx and Engels without really taking into consideration all that had gone before and that communism, organised more or less into a loose movement, was created by artisans and workers as a result of their practical experiences in the French Revolution and the events of the 1830s, as well as their continuing theoretical labours. -

Karl Marx: Communist As Religious Eschatologist

Karl Marx: Communist as Religious Eschatologist Murray N. Rothbard* Marx as Millennia1 Communist he key to the intricate and massive system of thought created by Karl Marx is at bottom a simple one: Karl Marx was a Tcommunist. A seemingly trite and banal statement set along- side Marxism's myriad of jargon-ridden concepts in philosophy, eco- nomics, and culture, yet Marx's devotion to communism was his crucial focus, far more central than the class struggle, the dialectic, the theory of surplus value, and all the rest. Communism was the great goal, the vision, the desideratum, the ultimate end that would make the sufferings of mankind throughout history worthwhile. History is the history of suffering, of class struggle, of the exploitation of man by man. In the same way as the return of the Messiah, in Christian theology, will put an end to history and establish a new heaven and a new earth, so the establishment of communism would put an end to human history. And just as for post-millennia1 Chris- tians, man, led by God's prophets and saints, will establish a Kingdom of God on Earth (for pre-millennials, Jesus will have many human assistants in setting up such a kingdom), so, for Marx and other schools of communists, mankind, led by a vanguard of secular saints, will establish a secularized Kingdom of Heaven on earth. In messianic religious movements, the millennium is invariably established by a mighty, violent upheaval, an Armageddon, a great apocalyptic war between good and evil. After this titanic conflict, a millennium, a new age, of peace and harmony, of the reign of justice, will be installed upon the earth. -

Requiem for Marx and the Social and Economic Systems Created in His Name

REQUIEM for RX Edited with an introduction by Yuri N. Maltsev ~~G Ludwig von Mises Institute l'VIISes Auburn University, Alabama 36849-5301 INSTITUTE Copyright © 1993 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute All rights reserved. Written permission must be secured from the publisher to use or reproduce any part of this book, except for brief quotations in critical review or articles. Published by Praxeology Press of the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama 36849. Printed in the United States ofAmerica. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 93-083763 ISBN 0-945466-13-7 Contents Introduction Yuri N. Maltsev ........................... 7 1. The Marxist Case for Socialism David Gordon .......................... .. 33 2. Marxist and Austrian Class Analysis Hans-Hermann Hoppe. .................. .. 51 3. The Marx Nobody Knows Gary North. ........................... .. 75 4. Marxism, Method, and Mercantilism David Osterfeld ........................ .. 125 5. Classical Liberal Roots ofthe Marxist Doctrine of Classes Ralph Raico ........................... .. 189 6. Karl Marx: Communist as Religious Eschatologist Murray N. Rothbard 221 Index 295 Contributors 303 5 The Ludwig von Mises Institute gratefully acknowledges the generosity ofits Members, who made the publication of this book possible. In particular, it wishes to thank the following Patrons: Mark M. Adamo James R. Merrell O. P. Alford, III Dr. Matthew T. Monroe Anonymous (2) Lawrence A. Myers Everett Berg Dr. Richard W. Pooley EBCO Enterprises Dr. Francis Powers Burton S. Blumert Mr. and Mrs. Harold Ranstad John Hamilton Bolstad James M. Rodney Franklin M. Buchta Catherine Dixon Roland Christopher P. Condon Leslie Rose Charles G. Dannelly Gary G. Schlarbaum Mr. and Mrs. William C. Daywitt Edward Schoppe, Jr. -

The Iwma and Its Precursors in London, C. 1830–1860

chapter � The iwma and Its Precursors in London, c. 1830–1860 Fabrice Bensimon The discussion of the origins of the International Working Men's Association (iwma) is as old as the Association itself. Right from its beginnings, the founding members defined what they saw as its origins. Since then, and in particu- lar with the development of a scientific study of the iwma in the twentieth century, several questions have been raised. The first is the militant origins in the various steps to the founding of the association on 28 September 1864. Who were these activists? Did the scheme of an international association of workers originate long before, or just recently? Was it a linear or rather a pro- tracted progress? What were the meanings that were given to “international- ism”? Another question relates to the longer-term assessment of the growth of working-class internationalism: did it exist, and if it did, according to what patterns did it develop? A possible third question is the study of its fortune: why was the iwma so different from previous attempts? Two broad approaches have been used. The “internal” one, best exempli- fied by the work of Arthur Lehning, has been the minute research on indi- viduals, on the small groups of refugees, trade unionists and political activists whose ideas and commitments led to the creation of the iwma.1 A more “ex- ternal” approach has consisted in addressing the issue of why this association in particular was so successful, while others had failed before: were economic circumstances different? Had labour markets changed? Had working-class practices been transformed in Britain and on the continent? And so on. -

Forum on Samir Amin's Proposal for A

JOURNAL OF WORLD-SYSTEMS RESEARCH ISSN: 1076-156X | Vol. 25 Issue 2 | DOI 10.5195/JWSR.2019.951 | jwsr.pitt.edu FORUM ON SAMIR AMIN’S PROPOSAL FOR A NEW INTERNATIONAL OF WORKERS AND PEOPLES Samir Amin, a leading scholar and co-founder of the world-systems tradition, died on August 12, 2018. Just before his death, he published, along with close allies, a call for ‘workers and the people’ to establish a ‘fifth international’ to coordinate support to progressive movements. To honor Samir Amin’s invaluable contribution to world-systems scholarship, we are pleased to present our readers with a selection of essays responding to Amin’s final message for today’s anti-systemic movements. This forum is being co-published between Globalizations, the Journal of World-Systems Research, and Pambazuka News. Readers can find additional essays and commentary in these outlets. The following essay has been published in Globalizations and is being reproduced here with permission. The Twenty-First Century Revolutions and Internationalism: A World- Historical Perspective Sahan Savas Karatasli University of North Carolina at Greensboro [email protected] Since the turn of the 21st century, we have been experiencing rapid intensification of revolutionary situations, social revolts and rebellions on a global scale (Badiou 2012; Žižek 2012; Mason 2012; Thernborn 2014; Chase-Dunn and Nagy 2019; Karatasli, Kumral, Scully, & Upadhyay 2014; Mason 2012; Therborn 2014; Žižek 2012). This is not an ordinary wave of social unrest. It belongs to one of the major world historical waves of mobilization (see Silver and Slater 1999) which has the potential to transform political structures, economic systems and social relations. -

The Iwma and Its Precursors in London, C. 1830–1860

chapter � The iwma and Its Precursors in London, c. 1830–1860 Fabrice Bensimon The discussion of the origins of the International Working Men's Association (iwma) is as old as the Association itself. Right from its beginnings, the founding members defined what they saw as its origins. Since then, and in particu- lar with the development of a scientific study of the iwma in the twentieth century, several questions have been raised. The first is the militant origins in the various steps to the founding of the association on 28 September 1864. Who were these activists? Did the scheme of an international association of workers originate long before, or just recently? Was it a linear or rather a pro- tracted progress? What were the meanings that were given to “international- ism”? Another question relates to the longer-term assessment of the growth of working-class internationalism: did it exist, and if it did, according to what patterns did it develop? A possible third question is the study of its fortune: why was the iwma so different from previous attempts? Two broad approaches have been used. The “internal” one, best exempli- fied by the work of Arthur Lehning, has been the minute research on indi- viduals, on the small groups of refugees, trade unionists and political activists whose ideas and commitments led to the creation of the iwma.1 A more “ex- ternal” approach has consisted in addressing the issue of why this association in particular was so successful, while others had failed before: were economic circumstances different? Had labour markets changed? Had working-class practices been transformed in Britain and on the continent? And so on. -

The German Labour Movement, 1830S–1840S: Early Efforts at Political Transnationalism

Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies ISSN: 1369-183X (Print) 1469-9451 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjms20 The German labour movement, 1830s–1840s: early efforts at political transnationalism Jürgen Schmidt To cite this article: Jürgen Schmidt (2019): The German labour movement, 1830s–1840s: early efforts at political transnationalism, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554283 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554283 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 15 Jan 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 307 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjms20 JOURNAL OF ETHNIC AND MIGRATION STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554283 The German labour movement, 1830s–1840s: early efforts at political transnationalism Jürgen Schmidt International Research Center “Work and Human Life Cycle in Global Perspective”, Humboldt-University, Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS It is a key idea that the German Labour Movement originated in the German labour movement; early nineteenth century abroad. In the more liberal atmosphere of political remittances; Paris, Brussels, Geneva and London political refugees and travelling transnationalism; working journeymen came together and founded associations. This turn of class formation; political refugees events should, however, not be seen solely within the analytical framework of class formation but also as part of the civil societal development of a transnational movement that fought for the acceptance of the workers as ‘real citizens’. -

THE PRINCIPLE of SELF-EMANCIPATION in MARX and ENGELS* Hal Draper

THE PRINCIPLE OF SELF-EMANCIPATION IN MARX AND ENGELS* Hal Draper THERE can be little doubt that Marx and Engels would have agreed with Lenin's nutshell definition of Marxism as "the theory and prac- tice of the proletarian revolution." In this violently compressed formula, the key component is not the unity of theory and practice; unfortunately that has become a platitude. Nor is it "revolution"; unfortunately that has become an ambiguity. The key is the word "proletarian"-the class-character component. But "proletarian revolution" too, very early, took on a considerable element of ambivalence, for it could be and was applied to two different patterns. In one pattern, the proletariat carries out its own liberating revolution. In the other, the proletariat is used to carry out a revolution. The first pattern is new; the second is ancient. But Marx and Engels were the first socialist thinkers to be sensitive to the distinction. Naturally so : since they were also the first to propose that, for the first time in the history of the world, the exploited bottom stratum of workers in society was in position to impress its own class character on a new social order. When Marx and Engels were crystallizing their views on this sub- ject, the revolutionary potentialities of the proletariat were already *The following essay is one chapter of a larger work in progress, on Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution, and concerns itself with only one aspect of Marx's views on the nature of proletarian revolution. Taken by itself, isolatedly, there is a danger that it may be interpreted in a onesided way, as counter- posing "self-emancipation" to class organization and political leadership.