Fighting Elections: an Example of Cross-Level Political Party Integration in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

OPPOSITION TO CONSCRIPTION IN ONTARIO 1917 A thesis submitted to the Department of History of the University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. % L,., A: 6- ''t, '-'rSily O* John R. Witham 1970 UMI Number: EC55241 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform EC55241 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE:IDEOLOGICAL OPPOSITION 8 CHAPTER TWO:THE TRADE UNIONS 33 CHAPTER THREE:THE FARMERS 63 CHAPTER FOUR:THE LIBERAL PARTI 93 CONCLUSION 127 APPENDIX A# Ontario Liberals Sitting in the House of Commons, May and December, 1917 • 131 APPENDIX B. "The Fiery Cross is now uplifted throughout Canada." 132 KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS 135 BIBLIOGRAPHY 136 11 INTRODUCTION The Introduction of conscription in 1917 evoked a deter mined, occasionally violent opposition from French Canadians. Their protests were so loud and so persistent that they have tended to obscure the fact that English Canada did not unanimous ly support compulsory military service. -

Mon 18 Apr 2005 / Lun 18 Avr 2005

No. 130A No 130A ISSN 1180-2987 Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative of Ontario de l’Ontario First Session, 38th Parliament Première session, 38e législature Official Report Journal of Debates des débats (Hansard) (Hansard) Monday 18 April 2005 Lundi 18 avril 2005 Speaker Président Honourable Alvin Curling L’honorable Alvin Curling Clerk Greffier Claude L. DesRosiers Claude L. DesRosiers Hansard on the Internet Le Journal des débats sur Internet Hansard and other documents of the Legislative Assembly L’adresse pour faire paraître sur votre ordinateur personnel can be on your personal computer within hours after each le Journal et d’autres documents de l’Assemblée législative sitting. The address is: en quelques heures seulement après la séance est : http://www.ontla.on.ca/ Index inquiries Renseignements sur l’index Reference to a cumulative index of previous issues may be Adressez vos questions portant sur des numéros précédents obtained by calling the Hansard Reporting Service indexing du Journal des débats au personnel de l’index, qui vous staff at 416-325-7410 or 325-3708. fourniront des références aux pages dans l’index cumulatif, en composant le 416-325-7410 ou le 325-3708. Copies of Hansard Exemplaires du Journal Information regarding purchase of copies of Hansard may Pour des exemplaires, veuillez prendre contact avec be obtained from Publications Ontario, Management Board Publications Ontario, Secrétariat du Conseil de gestion, Secretariat, 50 Grosvenor Street, Toronto, Ontario, M7A 50 rue Grosvenor, Toronto (Ontario) M7A 1N8. Par 1N8. Phone 416-326-5310, 326-5311 or toll-free téléphone : 416-326-5310, 326-5311, ou sans frais : 1-800-668-9938. -

Lesson Plan with Activities: Political

LESSON PLAN POLITICAL PARTIES Recommended for Grade 10 Duration: Approximately 60 minutes BACKGROUND INFORMATION Parliamentary Roles: www.ola.org/en/visit-learn/about-ontarios-parliament/ parliamentary-roles LEARNING GOALS This lesson plan is designed to engage students in the political process through participatory activities and a discussion about the various political parties. Students will learn the differences between the major parties of Ontario and how they connect with voters, and gain an understanding of the important elements of partisan politics. INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION (10 minutes) Canada is a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy, founded on the rule of law and respect for rights and freedoms. Ask students which country our system of government is based on. Canada’s parliamentary system stems from the British, or “Westminster,” tradition. Since Canada is a federal state, responsibility for lawmaking is shared among one federal, ten provincial and three territorial governments. Canada shares the same parliamentary system and similar roles as other parliaments in the Commonwealth – countries with historic links to Britain. In our parliament, the Chamber is where our laws are debated and created. There are some important figures who help with this process. Some are partisan and some are non-partisan. What does it mean to be partisan/non-partisan? Who would be voicing their opinions in the Chamber? A helpful analogy is to imagine the Chamber as a game of hockey, where the political parties are the teams playing and the non-partisan roles as the people who make sure the game can happen (ex. referees, announcers, score keepers, etc.) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF ONTARIO POLITICAL PARTIES 01 EXPLANATION (5 minutes) Political Parties: • A political party is a group of people who share the same political beliefs. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Budget Speech

General inquiries regarding the 2002 Ontario Budget—Growth and Prosperity: Keeping the Promise should be directed to: Ministry of Finance 95 Grosvenor Street, Queen’s Park Frost Building North, 3rd Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 1Z1 Telephone: (416) 325-0333 or call: Ministry of Finance Information Centre Toll-free English inquiries 1-800-337-7222 Toll-free French inquiries 1-800-668-5821 Teletypewriter (TTY) 1-800-263-7776 For electronic copies of this document, visit our Web site at http://www.gov.on.ca/FIN/hmpage.html Printed copies are available free from: Publications Ontario 880 Bay Street, Toronto, Ontario M7A 1N8 Telephone: (416) 326-5300 Toll-free: 1-800-668-9938 TTY Toll-free: 1-800-268-7095 Web site: www.publications.gov.on.ca Photos courtesy of J.M. Gabel and Renée Samuel. © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2002 ISBN 0-7794-3192-8 Ce document est disponible en français sous le titre : Budget de l’Ontario 2002—Croissance et prospérité : Tenir promesse GROWTH AND PROSPERITY: KEEPING THE PROMISE 1 ■■■ VALUES AND CHOICES Mr. Speaker, I am pleased to table today Ontario’s fourth consecutive balanced budget. This government is keeping its promise of growth and prosperity for Ontario. On February 14, 1967, the first Ontario Treasurer to come from Exeter, the Honourable Charles MacNaughton, described the challenge facing all Provincial Treasurers. In preparing a budget, he said, “We tread the slender tightrope between the reasonable expectations of our people for government services— and a constant awareness of the burdens on the taxpayer.” Thirty-five years later, Mr. -

C,Anadä LIBERÄL PÄRÏY ORGAI{IZÂTIOII AI{D

N,flonalLtbrav Bibliothèque nationale l*l du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliog raphic Services Branch des services bibliograPhiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) K1A ON4 K.lA ON4 Yout l¡le Volre élérence Our lile Noue rclércnce The author has granted an L'auteur a accordé une licence irrevocable non-exclus¡ve licence irrévocable et non exclus¡ve allowing the National Library of permettant à la Bibliothèque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell cop¡es of reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa thèse in any form or format, making de quelque manière et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette thèse à Ia disposition des personnes intéressées. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriété du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qu¡ protège sa Neither the thesis nor substantial thèse. Ni la thèse ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent être imprimés ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisation. ISBN 0-612-13090_8 C,anadä LIBERÄL PÄRÏY ORGAI{IZÂTIOII AI{D }'ANITOBA'S 1995 PROVINCIAL ELECTION BY ROBERT ANDREIJ DRI'I'IMOITD A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfiilment of the requirements of the degree of }TASIER OF ARTS @ 1996 Permission has been granted to the LIBRARY OF THE LTNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA to lend or sell copies of this thesis, to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and LIBRARY MICROFILMS to publish an abstract of this thesis. -

In Crisis Or Decline? Selecting Women to Lead Provincial Parties in Government

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Arts Arts Research & Publications 2018-06 In Crisis or Decline? Selecting Women to Lead Provincial Parties in Government Thomas, Melanee Cambridge University Press Thomas, M. (2018). In Crisis or Decline? Selecting Women to Lead Provincial Parties in Government. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique, 51(2), 379-403. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/107552 journal article Unless otherwise indicated, this material is protected by copyright and has been made available with authorization from the copyright owner. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca In Crisis or Decline? Selecting Women to Lead Provincial Parties in Government By Melanee Thomas Associate Professor Department of Political Science University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Abstract: The majority of Canada’s women premiers were selected to that office while their parties held government. This is uncommon, both in the comparative literature and amongst premiers who are men. What explains this gendered selection pattern to Canada’s provincial premiers’ offices? This paper explores the most common explanation found in the comparative literature for women’s emergence as leaders of electorally competitive parties and as chief political executives: women are more likely to be selected when that party is in crisis or decline. Using the population of women provincial premiers in Canada as case studies, evidence suggests 3 of 8 women premiers were selected to lead parties in government that were in crisis or decline; a fourth was selected to lead a small, left-leaning party as predicted by the literature. -

Report the 2016 Saskatchewan Provincial Election: The

Canadian Political Science Review Vol. 13, No. 1, 2019-20, 97-122 ISBN (online) 1911-4125 Journal homepage: https://ojs.unbc.ca/index.php/cpsr Report The 2016 Saskatchewan Provincial Election: The Solidification of an Uncompetitive Two-Party Leader-Focused System or Movement to a One-Party Predominant System? David McGrane Department of Political Studies, St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan – Email address: [email protected] Tom McIntosh Department of Political Science, University of Regina James Farney Department of Political Science, University of Regina Loleen Berdahl Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan Gregory Kerr Vox Pop Labs Clifton Van Der Liden Vox Pop Labs Abstract This article closely examines campaign dynamics and voter behaviour in the 2016 Saskatchewan provincial election. Using a qualitative assessment of the events leading up to election day and data from an online vote compass gathered during the campaign period, it argues that the popularity of the incumbent Premier, Brad Wall, was the decisive factor explaining the Saskatchewan Party’s success. Résumé Ce texte examine de près les dynamiques de la campagne et le comportement des électeurs lors des élections provinciales de 2016 en Saskatchewan. On fait une évaluation qualitative des événements qui ont précédé le jour du scrutin et une analyse des données d’une boussole de vote en ligne recueillies au cours de la campagne électorale. On souligne que la popularité du premier ministre Brad Wall était le facteur décisif qui explique le succès du le Parti saskatchewannais . Key words: Saskatchewan, provincial elections, Saskatchewan Party, Brad Wall, New Democratic Party of Saskatchewan, CBC Vote Compass Mots-clés: Saskatchewan, élections provinciales, le Parti saskatchewannais, Brad Wall, le Nouveau parti démocratique de la saskatchewan David McGrane et al 98 Introduction Writing about the 2011 Saskatchewan election, McGrane et al. -

The New Canadian Federal Dynamic What Does It Mean for Canada-US Relations? Canada’S Political Spectrum

The New Canadian Federal Dynamic What does it mean for Canada-US Relations? Canada’s Political Spectrum Leader: Justin Trudeau Interim Leader: Rona Leader: Thomas Mulcair Ambrose Party Profile: Social Party Profile: Populist, liberal policies, historically Party Profile: Social democratic fiscally responsible liberal/conservative, socialist/union roots fiscally pragmatic Supporter Base: Urban Supporter Base: Canada, Atlantic Supporter Base: Quebec, Urban Canada Provinces Suburbs, rural areas, Western provinces Leader: Elizabeth May Leader: Vacant Party Profile: Non-violence, social Party Profile: Protect/Defend justice and sustainability Quebec interests, independence Supporter Base: British Supporter Base: Urbana & rural Columbia, Atlantic Provinces Quebec Left Leaning Right Leaning 2 In Case You Missed It... Seats: 184 Seats: 99 Seats: 44 Popular Vote: 39.5% Popular Vote: 31.9% Popular Vote: 19.7% • Swept Atlantic Canada • Continue to dominate in the • Held rural Québec • Strong showing in Urban Prairies, but support in urban • Performed strongly across Canada – Ontario, Québec, and centres is cracking Vancouver Island and coastal B.C. B.C. 3 Strong National Mandate Vote Driven By • Longest campaign period in Canadian history – 78 Days • Increase in 7% in voter turnout • “Change” sentiment, positive messaging…. sound familiar? 4 The Liberal Government The Right Honourable Justin Trudeau Prime Minister “…a Cabinet that looks like Canada”. • 30 Members, 15 women • 2 aboriginal • 5 visible minorities • 12 incumbents • 7 previous Ministerial -

Canadian Politics

Canadian Politics Outline ● Executive (Crown) ● Legislative (Parliament) ● Judicial (Supreme Court) ● Elections ● Provinces (and Territories) Executive Crown ● Canada is a constitutional monarchy ● The Queen of Canada is the head of Canada ● These days, the Queen is largely just ceremonial – But the Governor General does have some real powers Crown ● Official title is long – In English: Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, Canada and Her other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. – In French: Elizabeth Deux, par la grâce de Dieu Reine du Royaume-Uni, du Canada et de ses autres royaumes et territoires, Chef du Commonwealth, Défenseur de la Foi. Legislative Parliament ● Sovereign (Queen/Governor General) ● Senate (Upper House) ● House of Commons (Lower House) Sovereign ● Represented by the Governor General ● Appoints the members of Senate – On recommendation of the PM ● Duties are largely ceremonial – However, can refuse to grant royal assent – Can refuse the call for an election Senate ● 105 members ● Started as equal representation of Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime region ● But, over time... – Regional equality is not observed – Nor is representation-by-population Senate ● 24 seats for each major region ● Ontario, Québec ● Maritime provinces – 10 for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, 4 for PEI ● Western provinces – 6 for each of BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba ● Newfoundland and Labrador – 6 seats ● NWT, Yukon, Nunavut – 1 seat each Senate Populate per Senator (2006) -

Thestar.Com Is Strictly Prohibited Without the Prior Written Permission of Toronto Star Newspapers Limited

Sep. 29, 2003. 06:19 AM McGuinty targets Tory strongholds LATEST DEVELOPLMENTS > Speak Out: Your vote Liberal leader 'not taking anything for granted' > Tories resigned (Oct. 2) Tories 'not toast,' Eves tells TV interviewer > McGuinty looks ahead (Oct. 2) CAROLINE MALLAN > Editorial: Get out and vote (Oct. QUEEN'S PARK BUREAU CHIEF 2) > Attack makes Hampton's day ORILLIA—Looking for as wide a sweep as possible in Thursday's election, Liberal (Oct. 2) Leader Dalton McGuinty is making a push for seats in staunch Conservative > Urquhart: 5 reasons to turf Tories strongholds. > Eves flubs lines (Oct. 1) > Bolstering Tory troops (Sept. 28) > Budget could haunt Liberals (Sept. 27) > 'We've got momentum:' Hampton (Sept. 27) RELATED LINKS > Election page > Campaign promises > Key issues > Riding Profiles > Voices: Election mudslinging > Voices: Health, education top issues > Voices: Premier's performance With polls showing that Ontario voters are poised to hand the Liberals a large majority, the frontrunner has shifted gears and is using the final four days of the campaign to try and pick up seats that were previously seen as beyond his reach. McGuinty's tour swung through Barrie and Orillia yesterday. Today, he will be in North Bay, hometown of former premier Mike Harris. As the Liberals embarked on the new, aggressive approach, Premier Ernie Eves, dogged over the weekend by the poll results, was telling a TV interviewer ``we are not toast'' when told the Tories are losing the election. ``There is only one poll that counts . and that is on election day," Eves said on CTV's Question Period. -

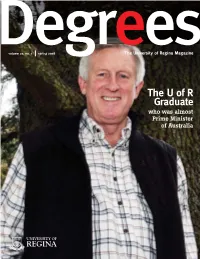

The U of R Graduate

volume 20, no. 1 spring 2008 The University of Regina Magazine TheUofR Graduate who was almost Prime Minister of Australia Luther College student Jeremy Buzash was among the competitors at the Regina Musical Club’s recital competition on May 10 in the Luther College Chapel. The competition included performances on piano, violin, flute, percussion and vocals. Up for grabs was a $1,000 scholarship. The winner was soprano Mary Joy Nelson BMus’01. Nelson graduated summa cum laude in 2006 from the vocal performance program at the University of Kentucky where she is completing a doctoral degree in voice. Photo by Trevor Hopkin, AV Services. Degrees spring 2008 1 Although you’ll find “The I read with interest your I was interested to read the Who’d have thought, after all University of Regina tribute to Professor Duncan fall 2007 article by Marie these years, that two issues in Magazine” on our front cover, Blewett in the Fall 2007 issue Powell Mendenhall on the arowofDegrees would have that moniker is not entirely of Degrees. I thought that I legacy of Duncan Blewett. I content that struck so close to accurate. That’s because in should balance the emphasis was one of a few hundred home? the truest sense Degrees is on psychoactive drug research students in his Psychology 100 I was an undergraduate your magazine. Of course we in the article with a story class in about 1969. I don’t and graduate student at the enjoy bringing you the stories about one of Professor remember what he looked like then University of of the terrific people who Blewett’s other interests.