Eu Response to the Refugee Crisis: the 'Hotspot' Approach" Executive Summary I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers No

KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers No. 54 September 1998 Maturity and Tasks of Hungarian Industry in the Context of Accession to the EU Summary Report of a KOPINT-DATORG Project KOPINT-DATORG Economic Research, Marketing and Computing Co. Ltd. H-1081 Budapest, Csokonai u. 3. KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers Editorial Board: László Csaba András Köves (Chairman) Gábor Oblath Iván Schweitzer László Szamuely Managing Editor: Iván Schweitzer This Summary report is a result of a project launched by the Hungarian Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism (IKIM) in 1997. The section activity of the in phase I. and II. and the elaboration of the project reports was co-ordinated by the KOPINT-DATORG Co. On the details see the I. chapter of this report ("Antecedents"). The following statements reflect the standpoint of the Project's expert team. Comments are welcome. KOPINT-DATORG Economic Research, Marketing and Computing Co. Ltd. H-1081 Budapest, Csokonai u. 3. Phone: (36-1) 303-9578 Fax: (36-1) 303-9588 ISSN 1216-0725 ISBN 963 7275 59 2 Maturity and Tasks of Hungarian Industry in the Context of Accession to the EU Summary Report of a KOPINT-DATORG Project Project chairman: Szabolcs Fazakas, Ex-Minister, IKIM Project director: János Deák, Managing Director, Chairman, KOPINT-DATORG Co. Project secretaries: Ms Mogyorósy, Dr Rózsa Halász, Chief Counsellor, IKIM Dr Zsuzsa Borszéki, Division Head, KOPINT-DATORG Co. Section heads, Phase I. I. Mining Dr János Fazekas, MD, Bakony Bauxite Mines Ltd. II. Textiles, leather, footwear Dr József Cseh, GS, Hungarian Light IndustrialAssociation III. Paper Miklós Galli, MD, Chairman, Dunapack Paper and Packaging Material PLC IV. -

HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent

Macro-Data Questionnaire - HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the dataset that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ____V114__________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party ---------------------- ----------------------- --------------- Gyula Horn Prime Minister MSZP Ferenc Baja Min. of Environment MSZP Judit Csiha Min. without portfolio supervising privatization MSZP Szabolcs Fazakas Min. of Industry MSZP Gyorgy Keleti Min. of Defence MSZP Peter Kiss Min. of Labour MSZP Mihaly Kokeny Min. of Health and Social Welfare MSZP Laszlo Kovacs Min. of Foreign Affairs MSZP Gabor Kuncze Min. of Interior SZDSZ Laszlo Lakos Min. of Agriculture MSZP Karoly Lotz Min. of Transportation and Communication SZDSZ Balint Magyar Min. of Education and Culture SZDSZ Peter Megyessy Min. of Finance MSZP Istvan Nikolits Min. without portfolio supervising secret services MSZP Pal Vastagh Min. of Justice MSZP 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Year Ideological Family International Organization Name of Political Party Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) ----------------------- ------- ------------------- ---------------- ---------- Fidesz-MPP 1988 Christian Dem. Liberal International until 2000, then moved to European People's P. FKGP 1930* Agrarian the European People's P. suspended the FKGP's membership in 1992 KDNP 1988 Christian Dem. The European People's P. suspended the KDNP's membership in 1997 MDF 1988 Christian Dem. European People's P. -

Hungarian Translation of the Main Programs of the XXX. Bálványos Summer University and Student Camp

Hungarian translation of the main programs of the XXX. Bálványos Summer University and Student Camp. The text in English has an informative character and may contain some inconsistencies with the official program. The organizers reserve the right to modify the program! The English program is permanently updated! _________________________________________________________________________________ XXX. Bálványos Summer University and Student Camp Băile Tușnad, 23–28 July 2019 One is the camp! Organisers Pro Minoritate Foundation The Hungarian Council of Youth (MIT) Key Partner Hungarian National Community in Transylvania Permanent programs Rákóczi-yard Ferenc Rákóczi II - memorial year – Travelling exhibition “PRO PATRIA ET LIBERTATE” To the memory of the reigning principal elections of Ferenc Rákóczi II, 1704-2019 The Hungarian Parliament declared the year of 2019 to be a commemorative year of Ferenc Rákóczi II. The HM Institute and Museum for War History has commissioned a travelling exhibition for the distinguished event, presenting the life of Ferenc Rákóczi II, the key events of the freedom fight of Rákóczi, and the armed forces of the freedom fight: the Kuruc and the Labanc. Opening ceremony: 24 July (Wednesday), 12:45 Wine tasting and pálinka tasting daily from 18:00 o’clock _________________________________________________________________________________ Krúdy-yard Gastro, wine and pálinka spots where speciality from Kistücsök, Anyukám mondta, Rókusfalvy birtok and Aston Catering can be tasted by participants. Restaurants refurbish the meals and dishes of traditional Hungarian cuisine within the framework of modern street food style, and may quench their thirst from the selection of nine wineries of the Carpathian basin (Southland, Highland, Transylvania and Little-Hungary), as well as may taste the best of Panyola Pálinkas. -

The Role of Defense Contractors in the Eastward Expansion

The Role of Defense Contractors in NATO’s Eastward Expansion By Jeremy Williams Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Michael Merlingen Word Count: 13,470 CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2011 Abstract NATO expansion has been a topic broadly covered by the academic community, with the moves for expansion after the fall of the Soviet Union and, therewith, the collapse of the Warsaw Pact military alliance that pitted the former communist Central and Eastern European states against the American-led West. However, while the academic community has discussed the theoretical motives for this expansion to a great extent, I look at in this thesis the role of a particular entity critical to the expansion of military alliances, defense contractors, in NATO’s expansion to Hungary, as one of the first ex-Warsaw Pact countries to join the Western military alliance. In my analysis, I ultimately identify four hypotheses that help to make inferences and assumptions based on the available data and personal consultation possible with such a niche, and yet highly confidential, topic. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements This thesis would have been impossible to complete without a number of people whose support, companionship and love were sometimes the only thing I had to fall back on. Thank you, Professor Merlingen, for your intense guidance and insight throughout my project. Thank you, Eszter Polgári for your unconditional support and friendship, particularly when it seemed like the world would end. -

Court of Auditors

12.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 344/1 IV (Notices) NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES COURT OF AUDITORS In accordance with the provisions of Article 287(1) and (4) of the TFEU and Articles 129 and 143 of Council Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1605/2002 of 25 June 2002 on the Financial Regulation applicable to the general budget of the European Communities, as last amended by Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1081/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Articles 139 and 156 of Council Regulation (EC) No 215/2008 of 18 February 2008 on the Financial Regulation applicable to the 10th European Development Fund the Court of Auditors of the European Union, at its meeting of 6 September 2012, adopted its ANNUAL REPORTS concerning the financial year 2011. The reports, together with the institutions' replies to the Court's observations, were transmitted to the authorities responsible for giving discharge and to the other institutions. The Members of the Court of Auditors are: Vítor Manuel da SILVA CALDEIRA (President), David BOSTOCK, Ioannis SARMAS, Igors LUDBORŽS, Jan KINŠT, Kersti KALJULAID, Karel PINXTEN, Ovidiu ISPIR, Nadejda SANDOLOVA, Michel CRETIN, Harald NOACK, Henri GRETHEN, Szabolcs FAZAKAS, Louis GALEA, Ladislav BALKO, Augustyn KUBIK, Milan Martin CVIKL, Rasa BUDBERGYTĖ, Lazaros S. LAZAROU, Gijs DE VRIES, Harald WÖGERBAUER, Hans Gustaf WESSBERG, Henrik OTBO, Pietro RUSSO, Ville ITÄLÄ, Kevin CARDIFF, Baudilio TOMÉ MUGURUZA. 12.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 344/3 ANNUAL REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE BUDGET (2012/C 344/01) 12.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 344/5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page General introduction . -

Goulash Justice for Goulash Communism?: Explaining Transitional Justice in Hungary Stan, Lavinia

www.ssoar.info Goulash justice for goulash Communism?: explaining transitional justice in Hungary Stan, Lavinia Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Stan, L. (2007). Goulash justice for goulash Communism?: explaining transitional justice in Hungary. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 7(2), 269-291. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-56066-8 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/1.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/1.0/deed.de Goulash Justice for Goulash Communism? 269 Goulash Justice for Goulash Communism? Explaining Transitional Justice in Hungary LAVINIA STAN There is a wide-spread belief in Hungary that the best revenge the new de- mocracy could take for the decades of communist rule it experienced at the hands of an unscrupulous and rapacious nomenklatura is to live well and to prosper quickly1. Economic redress for political injustice has been the Hungarian answer to de-communization and transitional justice, the two intertwined processes that have gained prominence throughout the post-communist Eastern European block. While its neighbors have struggled to deal with their dictatorial experience by re- examining their recent history, adopting lustration, bringing communist officials and secret agents to court, and opening the secret archives, Hungarians have em- braced the position that ”the best way to deal with the past is to do better now”2. -

Integráció Európába. Közép-Európai

Bíró-Nagy András INTEGRÁCIÓ EURÓPÁBA PARLAMENTI KÖTETEK Bíró-Nagy András Sorozatszerkesztő Erdős Csaba • Szabó Zsolt Integráció Európába Közép-európai képviselők az Európai Parlamentben Gondolat Kiadó – MTA TK PTI Budapest, 2018 A kötet megjelenését az MTA TK Politikatudományi Intézete támogatta TARTALOM Lektor: Dr. Arató Krisztina 1. BeveZeTéS 9 2. elMéleTi kereT – PoliTikuSi SZerePek éS aZ euróPai ParlaMenT 15 2.1. Politikusok és szerepeik – elméleti megközelítések 15 2.1.1. A strukturalista-funkcionalista szerepelmélet 16 2.1.2. Az interakcionista szerepelmélet 18 2.1.3. A motivációs elmélet 20 2.1.4. A racionális választás szerepelmélete 24 2.1.5. A kognitív racionalitás elmélete 26 2.1.6. A kutatás helye a szakirodalomban 28 © Bíró-Nagy András, 2017 2.2. Az Európai Parlament mint intézményi keret 30 2.2.1. Az Európai Parlament jogalkotási szerepének erősödése 34 2.2.2. Európai Parlament: három székhely, 24 nyelv 38 Minden jog fenntartva. Bármilyen másolás, sokszorosítás, 2.2.3. Együttműködésre ítélve: pártcsaládok az EP-ben 40 illetve adatfeldolgozó rendszerben való tárolás 2.2.4. A parlamenti jogalkotási munka központjai: a szakbizottságok 45 a kiadó előzetes írásbeli hozzájárulásához van kötve. 2.2.5. A képviselői aktivitás formái az Európai Parlamentben 47 A kiadó könyvei nagy kedvezménnyel az interneten is megrendelhetők. 2.2.6. Politikusi szerepek és az Európai Parlament 50 www.gondolatkiado.hu 2.3. Hipotézisek és módszertan 54 facebook.com/gondolat 3. köZéP-euróPai kéPviSelők A kiadásért felel Bácskai István aZ euróPai ParlaMenTBen 65 Szöveggondozó Gál Mihály Tördelő Sörfőző Zsuzsa 3.1. a közép-európai képviselők társadalmi-demográfiai háttere 66 ISBN 978 963 693 829 1 3.2. -

ADATOK AZ ORSZÁGGYŰLÉS TEVÉKENYSÉGÉRŐL 2017. Év ORSZÁGGYŰLÉS HIVATALA TÖRVÉNYHOZÁSI IGAZGATÓSÁG

ADATOK AZ ORSZÁGGYŰLÉS TEVÉKENYSÉGÉRŐL 2017. év ORSZÁGGYŰLÉS HIVATALA TÖRVÉNYHOZÁSI IGAZGATÓSÁG ADATOK AZ ORSZÁGGYŰLÉS 2017. évi TEVÉKENYSÉGÉRŐL 2017. január 1.-2017. december 31. Összeállította: az Országgyűlés Hivatala Készült: 2018. január 31. Kiadja: az Országgyűlés Hivatala, törvényhozási főigazgató-helyettes A táblázatokat készítette: Edelman Annamária, Tájékoztatási és Iromány-nyilvántartó Iroda, a Bizottsági Főosztály statisztikai munkacsoportja: dr. Palkó Katalin, Kiss Erika Gabriella, Vásárhelyi Pál, Hatvani Szabolcs és dr. Nagy Zoltán, továbbá a bizottsági titkárságok kollégái Közreműködött: Informatikai Belső Fejlesztési és Ügyfélszolgálati Főosztály Belső Fejlesztői Csoportja, Tóth Margit, Tájékoztatási és Iromány-nyilvántartó Iroda Milos Boglárka, Tájékoztatási és Iromány-nyilvántartó Iroda Szerkesztette: a Tájékoztatási és Iromány-nyilvántartó Iroda, Tájékoztatási és Módszertani Osztálya Lezárva: 2018. január 25. Internet: www.parlament.hu E-mail: [email protected] T A R T A L O M Oldal 1. KÉPVISELŐK 1.1. Mandátum-változások 1.1.1. Változások az Országgyűlés összetételében az alakuló ülés óta ........................................................... 1 1.1.2. A változások hatása a pártok képviselőcsoportjaira ............................................................................. 4 1.1.3. A pártok képviselőcsoportjainak valamint a független képviselők részesedése a parlamenti mandátumokból ............................................................................................................... 5 1.2. -

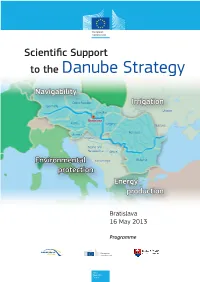

To the Danube Strategy

Scientific Support to the Danube Strategy Navigability Czech Republic Germany Irrigation Slovakia Ukraine Bratislava Austria Hungary Moldova Romania Slovenia Croatia Bosnia and Herzegovina Serbia Environmental Montenegro Bulgaria protection Energy production Bratislava 16 May 2013 Programme Joint Research Centre 08:00 – 09:00 Registration and welcome coffee 09:00 – 09:30 Welcome session Co-chairs: Dušan Čaplovič, Minister for Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic, and Dominique Ristori, Director-General of the Joint Research Centre, European Commission Opening statement by the Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic, H.E. Robert Fico Welcome by the Vice President of the European Commission, Maroš Šefčovič 09:30 – 10:20 Opening session Karlheinz Töchterle, Federal Minister for Science and Research, Austria Zoltán Cséfalvay, Minister of State for Economic Strategy, Hungary Mihnea Costoiu, Minister Delegate for Higher Education, Scientific Research and Technological Development, Romania Walter Deffaa, Director-General, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, European Commission Edit Herczog, Member of the European Parliament 10:20 – 13:00 Session 1: Towards a smartly specialised and innovative Danube region 10:20 Introduction and moderation by Vladimir Šucha, Deputy Director-General, Joint Research Centre, European Commission 10:30 Key note speeches on fostering the innovation in the Danube Region Szabolcs Fazakas, Member of the European Court of Auditors Susanne Burger, Director European Affairs, Federal -

Republic of Hungary EUR 1,000,000,000 3.50 Per Cent

Republic of Hungary EUR 1,000,000,000 3.50 per cent. Notes due 2016 Issue Price: 99.437 per cent. The issue price of the EUR 1,000,000,000 3.50 per cent. Notes due 2016 (the ‘‘Notes’’)ofthe Republic of Hungary (the ‘‘Republic’’ or ‘‘Hungary’’)is99.437 per cent. of their principal amount. Unless previously redeemed or cancelled, the Notes will be redeemed at their principal amount on the Interest Payment Date (as defined in the ‘‘Terms and Conditions of the Notes’’) falling on 18 July 2016. The Notes will bear interest from 18 January 2006 at the rate of 3.50 per cent. per annum payable annually in arrear on 18 July in each year commencing on the Interest Payment Date falling in July 2006. Payments on the Notes will be made in euro without deduction for or on account of taxes imposed or levied by the Republic of Hungary to the extent described under ‘‘Terms and Conditions of the Notes – Taxation’’. The Notes have not been, and will not be, registered under the United States Securities Act of 1933 (the ‘‘Securities Act’’) and are subject to United States tax law requirements. The Notes are being offered outside the United States by the Managers (as defined herein) in accordance with Regulation S under the Securities Act (‘‘Regulation S’’), and may not be offered, sold or delivered within the United States or to, or for the account or benefit of, U.S. persons except pursuant to an exemption from, or in a transaction not subject to, the registration requirements of the Securities Act. -

Research Fellows at the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies 1986-2013

RESEARCH FELLOWS AT THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR CONTEMPORARY GERMAN STUDIES 1986-2013 JOHN J. MCCLOY DISTINGUISHED FELLOWSHIP * Funded by the John M. Olin Foundation (New York City) 1986-1987 Professor Norbert Walter, Institut für Weltwirtschaft, Kiel Topic: "Demographic Trends and Economic Dynamism: The U.S. and the FRG" 1987-1988 Professor Helmut Willke, Universität Bielefeld Topic: "SDI as a Mixed-Motive Political Strategy: The German Response" 1988-1989 Professor Klaus Gretschmann, Universität Köln Topic: "The Three-Tiered German Tax Reform as Compared to the 1986 U.S. Tax Reform Act: Economic Pressure and Political Necessity" 1989-1990 Professor Paul J.J. Welfens, Universität Duisburg Topic: "Integrating Markets, Firms and Governments in the Economic Community: The Role of Germany in a Global Context" 1990-1991 Professor Steven Philip Kramer, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque Topic: "The Franco-German Relationship in an Age of German Unification" FORD FOUNDATION FELLOWSHIP IN GDR STUDIES * Funded by the Ford Foundation (New York City) 1988-1989 Professor Ann Phillips, Smith College, Northampton, MA Topic: "The East German Perspective on the East German - Soviet Relationship" 1989-1990 Professor Joyce Mushaben, University of Missouri, St. Louis Topic: "Through the Looking Glass: The Cultivation of Post-War National Identity in the German Democratic Republic" HOECHST CELANESE/SIEMENS FELLOWSHIP * Funded by the Hoechst Celanese Corporation and Siemens Corporation 1988-1989 Professor Christopher Allen, University of Georgia, Athens Topic: "The Politics of Regulating Domestic Capital Investment: Banks and Stock Markets in West Germany and the United States" 1989-1990 Professor Lily Gardner Feldman, Tufts University, Boston, MA Topic: "Germany's Rehabilitation: A Comparison of Relations with France, Israel and the United States" AICGS/DHI FELLOWSHIPS IN POST-WAR GERMAN HISTORY * Funded by the Volkswagen-Stiftung (Joint Program with the German Historical Institute) 1991-1992 Dr. -

Wednesday Afternoon, 21 June, Infopark, Budapest DAY 2

Draft Programme DAY 1 – Wednesday afternoon, 21 June, InfoPark, Budapest 14:00 Registration 14:30 Welcome and Opening Welcome by the conference Chair, Dr. Roland Strauss, Platte Strauss Partners Opening by Dr. Miklós Boda, President, National Office for Research and Technology and Dr. Gábor Szabó , President- CEO, InfoPark 15:00 Examples of how large and small enterprises innova te and co-operate Driving innovation – a challenge for industry and academia, Tamás Vahl, SAP (tbc) Going global from the beginning , Dr. Ferenc Darvas , Founder and President, Thales Nanotechnologies Individual meetings between small business and representatives of large companies can be arranged throughout the conference 16:00 Coffee Break 16:30 Presentation of EU projects, programmes and service s supporting innovative businesses From research ideas to business results , Laura Hernández-Saldaña , CORDIS – Community Research and Development Information Service Innovation Relay Centre Hungary , Budapest University of Technology and Economics – National Technical Information Centre and Library) IPR Helpdesk SME participation in EU Research projects, EU / Hungarian Grants for innovative small businesses, András Revai, Deputy Director , Innostart Participating in EU FP 6 research projects: talking from experience, Prof. Richárd Schwab, Semmelweis University Participating in EU funded projects: a practical experience, Dr. Szabolcs Katai, Director of EU Relations , IVSZ (The presentations also provide background information for the 'one-on-one' information sessions) 17:30 Networking reception Hosted by InfoPark and NKTH , building C (conference hall) DAY 2 – Thursday, 22 June, Hotel Béke, Budapest 08:30 Registration and Coffee 09:00 Welcome and Opening Welcome by the conference Chair, Dr. Roland Strauss, Platte Strauss Partners Opening by Dr.