Aicgs Policy Report #6 the Changing Face of Europe: Eu Enlargement and Implications for Transatlantic Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individual V. State: Practice on Complaints with the United Nations Treaty Bodies with Regards to the Republic of Belarus

Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus Volume I Collection of articles and documents The present collection of articles and documents is published within the framework of “International Law in Advocacy” program by Human Rights House Network with support from the Human Rights House in Vilnius and Civil Rights Defenders (Sweden) 2012 UDC 341.231.14 +342.7 (476) BBK 67.412.1 +67.400.7 (4Bel) I60 Edited by Sergei Golubok Candidate of Law, Attorney of the St. Petersburg Bar Association, member of the editorial board of the scientific journal “International justice” I60 “Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus”. – Vilnius, 2012. – 206 pages. ISBN 978-609-95300-1-7. The present collection of articles “Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus” is the first part of the two-volume book, that is the fourth publication in the series about international law and national legal system of the republic of Belarus, implemented by experts and alumni of the Human Rights Houses Network‘s program “International Law in Advocacy” since 2007. The first volume of this publication contains original writings about the contents and practical aspects of international human rights law concepts directly related to the Institute of individual communications, and about the role of an individual in the imple- mentation of international legal obligations of the state. The second volume, expected to be published in 2013, will include original analyti- cal works on the admissibility of individual considerations and the Republic of Belarus’ compliance with the decisions (views) by treaty bodies. -

Evolution of Belarusian-Polish Relations at the Present Stage: Balance of Interests

Журнал Белорусского государственного университета. Международные отношения Journal of the Belarusian State University. International Relations UDC 327(476:438) EVOLUTION OF BELARUSIAN-POLISH RELATIONS AT THE PRESENT STAGE: BALANCE OF INTERESTS V. G. SHADURSKI а aBelarusian State University, Nezavisimosti avenue, 4, Minsk, 220030, Republic of Belarus The present article is dedicated to the analysis of the Belarusian-Polish relations’ development during the post-USSR period. The conclusion is made that despite the geographical neighborhood of both countries, their cultural and historical proximity, cooperation between Minsk and Warsaw didn’t comply with the existing capacity. Political contradictions became the reason for that, which resulted in fluctuations in bilateral cooperation, local conflicts on the inter-state level. The author makes an attempt to identify the main reasons for a low level of efficiency in bilateral relations and to give an assessment of foreign factors impact on Minsk and Warsaw policies. Key words: Belarusian-Polish relations; Belarusian foreign policy; Belarusian and Polish diplomacy; historical policy. ЭВОЛЮЦИЯ БЕЛОРУССКО-ПОЛЬСКИХ ОТНОШЕНИЙ НА СОВРЕМЕННОМ ЭТАПЕ: ПОИСК БАЛАНСА ИНТЕРЕСОВ В. Г. ШАДУРСКИЙ 1) 1)Белорусский государственный университет, пр. Независимости, 4, 220030, г. Минск, Республика Беларусь В представленной публикации анализируется развитие белорусско-польских отношений на протяжении периода после распада СССР. Делается вывод о том, что, несмотря на географическое соседство двух стран, их культурную и историческую близость, сотрудничество Минска и Варшавы не соответствовало имеющемуся потенциалу. При- чиной тому являлись политические разногласия, следствием которых стали перепады в двухстороннем взаимодей- ствии, частые конфликты на межгосударственном уровне. Автор пытается выяснить основные причины невысокой эффективности двусторонних связей, дать оценку влияния внешних факторов на политику Минска и Варшавы. -

Belarus Epr Atlas Belarus 110

epr atlas 109 Belarus epr atlas belarus 110 Ethnicity in Belarus Power relations The demographic majority in Belarus are the Byelorussians, they operate as senior partners next to the largest minority, the Russians. The Russians are junior partners. Russians of Belarus represent an advantaged minority. The current regime of Alexander Lukashenka is decidedly pro-Russian in economic, political and cultural terms. The Russian and Belarusian languages are very similar. And most Belarusians hold a clear affinity to and identification for Russia and the Soviet Union in general. Many of the former differences between the Belarusian and Russian culture and languages were diminished during Soviet rule. A large part of the Belarusian population identi- fies with Russia (161). The Russian and Byelorussian languages have 161 [Eke Kuzio, 2000] equal legal status, but, in practice, Russian is the primary language used by the government (162). Russians have also a special status in 162 [U.S. State Department, 2005 - 2009] Belarus, because the country is dependent on Russia (trade, energy) (163). Therefore the Belarusian government adopted inclusive poli- 163 [Hancock, 2006] cies towards the Russian minority. The ruling party for example, is ethnically mixed and extremely pro-Russian (164). 164 [Eke Kuzio, 2000] The Polish minority was powerless until 2004, then they be- came discriminated. Starting in May 2005, there was increased governmental and societal discrimination against the ethnic Pol- ish population (165). The government interfered in the internal af- 165 [U.S. State Department, 2005 - 2009] fairs of the most important Polish NGO: The Union of Belarusian Poles held a congress to elect new leaders. -

KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers No

KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers No. 54 September 1998 Maturity and Tasks of Hungarian Industry in the Context of Accession to the EU Summary Report of a KOPINT-DATORG Project KOPINT-DATORG Economic Research, Marketing and Computing Co. Ltd. H-1081 Budapest, Csokonai u. 3. KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers Editorial Board: László Csaba András Köves (Chairman) Gábor Oblath Iván Schweitzer László Szamuely Managing Editor: Iván Schweitzer This Summary report is a result of a project launched by the Hungarian Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism (IKIM) in 1997. The section activity of the in phase I. and II. and the elaboration of the project reports was co-ordinated by the KOPINT-DATORG Co. On the details see the I. chapter of this report ("Antecedents"). The following statements reflect the standpoint of the Project's expert team. Comments are welcome. KOPINT-DATORG Economic Research, Marketing and Computing Co. Ltd. H-1081 Budapest, Csokonai u. 3. Phone: (36-1) 303-9578 Fax: (36-1) 303-9588 ISSN 1216-0725 ISBN 963 7275 59 2 Maturity and Tasks of Hungarian Industry in the Context of Accession to the EU Summary Report of a KOPINT-DATORG Project Project chairman: Szabolcs Fazakas, Ex-Minister, IKIM Project director: János Deák, Managing Director, Chairman, KOPINT-DATORG Co. Project secretaries: Ms Mogyorósy, Dr Rózsa Halász, Chief Counsellor, IKIM Dr Zsuzsa Borszéki, Division Head, KOPINT-DATORG Co. Section heads, Phase I. I. Mining Dr János Fazekas, MD, Bakony Bauxite Mines Ltd. II. Textiles, leather, footwear Dr József Cseh, GS, Hungarian Light IndustrialAssociation III. Paper Miklós Galli, MD, Chairman, Dunapack Paper and Packaging Material PLC IV. -

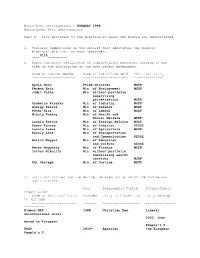

HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent

Macro-Data Questionnaire - HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the dataset that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ____V114__________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party ---------------------- ----------------------- --------------- Gyula Horn Prime Minister MSZP Ferenc Baja Min. of Environment MSZP Judit Csiha Min. without portfolio supervising privatization MSZP Szabolcs Fazakas Min. of Industry MSZP Gyorgy Keleti Min. of Defence MSZP Peter Kiss Min. of Labour MSZP Mihaly Kokeny Min. of Health and Social Welfare MSZP Laszlo Kovacs Min. of Foreign Affairs MSZP Gabor Kuncze Min. of Interior SZDSZ Laszlo Lakos Min. of Agriculture MSZP Karoly Lotz Min. of Transportation and Communication SZDSZ Balint Magyar Min. of Education and Culture SZDSZ Peter Megyessy Min. of Finance MSZP Istvan Nikolits Min. without portfolio supervising secret services MSZP Pal Vastagh Min. of Justice MSZP 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Year Ideological Family International Organization Name of Political Party Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) ----------------------- ------- ------------------- ---------------- ---------- Fidesz-MPP 1988 Christian Dem. Liberal International until 2000, then moved to European People's P. FKGP 1930* Agrarian the European People's P. suspended the FKGP's membership in 1992 KDNP 1988 Christian Dem. The European People's P. suspended the KDNP's membership in 1997 MDF 1988 Christian Dem. European People's P. -

Hungarian Translation of the Main Programs of the XXX. Bálványos Summer University and Student Camp

Hungarian translation of the main programs of the XXX. Bálványos Summer University and Student Camp. The text in English has an informative character and may contain some inconsistencies with the official program. The organizers reserve the right to modify the program! The English program is permanently updated! _________________________________________________________________________________ XXX. Bálványos Summer University and Student Camp Băile Tușnad, 23–28 July 2019 One is the camp! Organisers Pro Minoritate Foundation The Hungarian Council of Youth (MIT) Key Partner Hungarian National Community in Transylvania Permanent programs Rákóczi-yard Ferenc Rákóczi II - memorial year – Travelling exhibition “PRO PATRIA ET LIBERTATE” To the memory of the reigning principal elections of Ferenc Rákóczi II, 1704-2019 The Hungarian Parliament declared the year of 2019 to be a commemorative year of Ferenc Rákóczi II. The HM Institute and Museum for War History has commissioned a travelling exhibition for the distinguished event, presenting the life of Ferenc Rákóczi II, the key events of the freedom fight of Rákóczi, and the armed forces of the freedom fight: the Kuruc and the Labanc. Opening ceremony: 24 July (Wednesday), 12:45 Wine tasting and pálinka tasting daily from 18:00 o’clock _________________________________________________________________________________ Krúdy-yard Gastro, wine and pálinka spots where speciality from Kistücsök, Anyukám mondta, Rókusfalvy birtok and Aston Catering can be tasted by participants. Restaurants refurbish the meals and dishes of traditional Hungarian cuisine within the framework of modern street food style, and may quench their thirst from the selection of nine wineries of the Carpathian basin (Southland, Highland, Transylvania and Little-Hungary), as well as may taste the best of Panyola Pálinkas. -

The Role of Defense Contractors in the Eastward Expansion

The Role of Defense Contractors in NATO’s Eastward Expansion By Jeremy Williams Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Michael Merlingen Word Count: 13,470 CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2011 Abstract NATO expansion has been a topic broadly covered by the academic community, with the moves for expansion after the fall of the Soviet Union and, therewith, the collapse of the Warsaw Pact military alliance that pitted the former communist Central and Eastern European states against the American-led West. However, while the academic community has discussed the theoretical motives for this expansion to a great extent, I look at in this thesis the role of a particular entity critical to the expansion of military alliances, defense contractors, in NATO’s expansion to Hungary, as one of the first ex-Warsaw Pact countries to join the Western military alliance. In my analysis, I ultimately identify four hypotheses that help to make inferences and assumptions based on the available data and personal consultation possible with such a niche, and yet highly confidential, topic. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements This thesis would have been impossible to complete without a number of people whose support, companionship and love were sometimes the only thing I had to fall back on. Thank you, Professor Merlingen, for your intense guidance and insight throughout my project. Thank you, Eszter Polgári for your unconditional support and friendship, particularly when it seemed like the world would end. -

Socialeconomic and Committee

EUROPEAN COMMUNIT!ES BULLETIN 9 SOCIALECONOMIC AND COMMITTEE a oIJJ EN THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE FACTS AND FIGURES - November 1996 OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Chair 4. Sub-committees Ic.m"-l 2rrs The decision-making o,*" l- The ESC has the right to set up temporary sub-com- lP.dhhenl I process in the Com- President: Tom JENKINS -lI mittees, for specrfic issues. These sub-committees (United Kingdom - Workers) munity (simplified) tt operate on the same Iines as the sections. ,, ?#ff [''"'l Vrce-presrdents: Giacomo REGALDO | @hhGl\ | / | 5. Plenary session (ltaly - Employers) +/ \t t**i l f k* I t&dm;-l..ti @M;l As a rule, the full Committee meets in plenary ses- Johannes JASCHICK ................*1 .* l*..,*.n Mamh. coud I sron ten times a year. At the plenary sessions, opin- (Germany - Various Interests) "-*, Md + drd6 I ions are adopted on the basis of section opinions by a 1\ /z 34 Secretary-general: AdTianoGRAZIOSI \ fc bm l / simple majority. They are forwarded to the institu- \ co.rn* / trons and published in the Official Journal of the Eu- L Origins "9,f"' ] 'o*"' ropean Communities. The ESC was set up by the 1957 Rome Treaties rn order to involve economic and social interest groups 6. Relations with economic and social councils in the establishment of the common market and to The ESC maintains regular links with regional and The president is responsrble for the orderly conduct provide institutional machinery for briefing the Eu- national economrc and social councils throughout the ropean Commission and the Council of Mimsters on of the Committee's business. -

European Union and Population and Housing Census Around the Year 2001

European Union and Population and Housing Censuses around the year 20011 Aarno Laihonen Eurostat/E4 Jean Monnet Building L-2920 Luxembourg [email protected] Countries around the world have started preparations for the 2000 census round. Population and housing censuses are still a major source of demographic and socio-economic statistics in most countries. They are also a unique source of geographically detailed data. The demand for these has increased rapidly in recent years – led, for example, by development of powerful geographic information systems applications in spatial analysis, and by logistics, physical planning and managing transportation networks. This is why censuses are still conducted in most countries, even if the relative cost of a traditional census has risen to a level more and more difficult to justify in an age of government budget cuts. Content of censuses has been coordinated internationally under United Nations recommendations. The UN regional commission for Europe (ECE) prepared recommendations for Europe for census rounds 1960, 1970, 1980 and 1990. The EU prepared its own programmes to satisfy Community data needs for census rounds 1980 and 1990. These relied on UN/ECE recommendations and were based on Council Directives 73/403 and 87/287. The final workshop of the series on the theme Censuses beyond 2000 will be held in France in the second half of 1999. The workshop proceedings have been published jointly by the organising national statistical institutes and Eurostat and are available from either. Changing census methodology Increasing cost pressures and pressures to reduce respondent burden have created a strong intensive for the countries in Europe to seek new solutions in census data collection and more effective methods of data processing. -

Court of Auditors

12.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 344/1 IV (Notices) NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES COURT OF AUDITORS In accordance with the provisions of Article 287(1) and (4) of the TFEU and Articles 129 and 143 of Council Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1605/2002 of 25 June 2002 on the Financial Regulation applicable to the general budget of the European Communities, as last amended by Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1081/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Articles 139 and 156 of Council Regulation (EC) No 215/2008 of 18 February 2008 on the Financial Regulation applicable to the 10th European Development Fund the Court of Auditors of the European Union, at its meeting of 6 September 2012, adopted its ANNUAL REPORTS concerning the financial year 2011. The reports, together with the institutions' replies to the Court's observations, were transmitted to the authorities responsible for giving discharge and to the other institutions. The Members of the Court of Auditors are: Vítor Manuel da SILVA CALDEIRA (President), David BOSTOCK, Ioannis SARMAS, Igors LUDBORŽS, Jan KINŠT, Kersti KALJULAID, Karel PINXTEN, Ovidiu ISPIR, Nadejda SANDOLOVA, Michel CRETIN, Harald NOACK, Henri GRETHEN, Szabolcs FAZAKAS, Louis GALEA, Ladislav BALKO, Augustyn KUBIK, Milan Martin CVIKL, Rasa BUDBERGYTĖ, Lazaros S. LAZAROU, Gijs DE VRIES, Harald WÖGERBAUER, Hans Gustaf WESSBERG, Henrik OTBO, Pietro RUSSO, Ville ITÄLÄ, Kevin CARDIFF, Baudilio TOMÉ MUGURUZA. 12.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 344/3 ANNUAL REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE BUDGET (2012/C 344/01) 12.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 344/5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page General introduction . -

Statement by the Turkish Government on 14

PERCEPTIONS JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS December 1997-February 1998 Volume II - Number 4 STATEMENT BY THE TURKISH MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS ON 14 DECEMBER 1997, CONCERNING THE PRESIDENCY CONCLUSIONS OF THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL HELD ON 12-13 DECEMBER 1997 IN LUXEMBOURG At the Luxembourg meeting of the Heads of State and Government of the member states of the European Union, held on 12-13 December 1997, a decision was taken to commence accession negotiations with “Cyprus” on the basis of the unilateral application of the Greek Cypriot Administration of Southern Cyprus. Turkey deems it useful to bring the following to the attention of EU members and the international community regarding the aforesaid decision and the repercussions that will ensue: 1. The 1959-60 Agreements regarding Cyprus were concluded among five parties, namely, Turkey, Greece, the United Kingdom and the Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot communities. These agreements have established a balance not only between the two national communities in the island, but also between Turkey and Greece, with a view to preserving peace and stability in the region. The aforementioned agreements have stipulated the political and legal equality of the two sides in Cyprus, and designated the Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot communities as the co-founders of the 1960 Republic. In this context, in addition to the United Kingdom which has maintained bases on the island, Turkey and Greece, as Guarantor Powers and motherlands, were given equal rights and obligations for the maintenance of the internal and external balance established over Cyprus. Ever since 1963 when the partnership state established in 1960 was destroyed by force of arms by the Greek Cypriots, there has not been a single state, government or parliament competent to represent the whole island. -

The Belarusian Minority in Poland

a n F P 7 - SSH collaborative research project [2008 - 2 0 1 1 ] w w w . e n r i - e a s t . n e t Interplay of European, National and Regional Identities: Nations between States along the New Eastern Borders of the European Union Series of project research reports Contextual and empirical reports on ethnic minorities in Central and Eastern Europe Research Report #10 Belarus The Belarusian Minority Germany in Poland Hungary Authors: Konrad Zieliński Latvia Magdalena Cześniak-Zielińska | Ilona Matysiak Lithuania Anna Domaradzka | Łukasz Widła Hans-Georg Heinrich | Olga Alekseeva Poland Russia Slovakia Series Editors: Ukraine Hans-Georg Heinrich | Alexander Chvorostov Project primarily funded under FP7-SSH programme Project host and coordinator EUROPEAN COMMISSION www.ihs.ac.at European Research Area 2 ENRI - E a s t R e s e a r c h Report #10: The Belarusian Minority in Poland About the ENRI-East research project (www.enri-east.net) The Interplay of European, National and Regional Identities: Nations between states along the new eastern borders of the European Union (ENRI-East) ENRI-East is a research project implemented in 2008-2011 and primarily funded by the European Commission under the Seventh Framework Program. This international and inter-disciplinary study is aimed at a deeper understanding of the ways in which the modern European identities and regional cultures are formed and inter-communicated in the Eastern part of the European continent. ENRI-East is a response to the shortcomings of previous research: it is the first large-scale comparative project which uses a sophisticated toolkit of various empirical methods and is based on a process-oriented theoretical approach which places empirical research into a broader historical framework.