Goulash Justice for Goulash Communism?: Explaining Transitional Justice in Hungary Stan, Lavinia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HIST 112 Sheet 2

South Dakota State University HIST 112 - World Civilization Concepts addressed: Changing face of economic systems: communism, socialism, and capitalism 1. Communism, 1945-1989/1991 a. After WWII, Soviet Union continued to challenge capitalist world with regard to rates of economic growth but stagnation by later 1960s b. Amongst eastern bloc, Czechoslovakia and East Germany reached highest levels of development (started from higher level of development) c. Adjustments in Hungary following Revolution of 1956: "Goulash Communism" i. Combined limited private enterprise (very small businesses) and halt to collectivization of farms with state-directed big business and capital ownership ii. Slightly increased openness of culture to criticism, creativity d. Prague Spring (1968) demonstrated limits to possible reform i. Government under Alexander Dubcek sought means to open political system to debate, possibly to multiple parties ii. Economic stagnation inspired revisions of planning to suggest ways to incorporate greater flexibility on local level into overall system of state direction iii. Period of cultural opening and widespread debate within civil society crushed by Warsaw Pact tanks/Moscow directives iv. Dubcek replaced by Moscow-obedient Gustav Husak - period of "normalization" followed that entailed passive acceptance on the part of citizens in return for basic assurances in job, health, housing, education e. Solidarity in Poland challenged notion of country as a "workers' state" i. Strikes at Gdansk shipyard and elsewhere in 1980 led by charismatic mechanic Lech Walesa ii. Government capitulated but then established martial law in order to rein in protests, new movements f. Stagnation under Leonid Brezhnev in USSR - little economic growth, clear that USSR unable to compete with West in tech revolution of later 20th century (behind on computer development, communications, etc.) g. -

Whither Communism: a Comparative Perspective on Constitutionalism in a Postsocialist Cuba Jon L

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2009 Whither Communism: A Comparative Perspective on Constitutionalism in a Postsocialist Cuba Jon L. Mills University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Daniel Ryan Koslosky Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Jon Mills & Daniel Ryan Koslosky, Whither Communism: A Comparative Perspective on Constitutionalism in a Postsocialist Cuba, 40 Geo. Wash. Int'l L. Rev. 1219 (2009), available at, http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/522 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHITHER COMMUNISM: A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE ON CONSTITUTIONALISM IN A POSTSOCIALIST CUBA JON MILLS* AND DANIEL RYAN KOSLOSIc4 I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 1220 II. HISTORY AND BACKGROUND ............................ 1222 A. Cuban ConstitutionalLaw .......................... 1223 1. Precommunist Legacy ........................ 1223 2. Communist Constitutionalism ................ 1225 B. Comparisons with Eastern Europe ................... 1229 1. Nationalizations in Eastern Europe ........... 1230 2. Cuban Expropriations ........................ 1231 III. MODES OF CONSTITUTIONALISM: A SCENARIO ANALYSIS. 1234 A. Latvia and the Problem of ConstitutionalInheritance . 1236 1. History, Revolution, and Reform ............. 1236 2. Resurrecting an Ancien Rgime ................ 1239 B. Czechoslovakia and Poland: Revolutions from Below .. 1241 1. Poland's Solidarity ........................... 1241 2. Czechoslovakia's Velvet Revolution ........... 1244 3. New Constitutionalism ....................... 1248 C. Hungary's GradualDecline and Decay .............. -

Barmscoll/Nagy J / J 2 Nagy,Ferenc, 1903-1979

BARMsColl/Nagy J / J 2 Nagy, Ferenc, 1903-1979. Papers, 1940-1979. 39 linear ft. (a.21,500 Items In 93 boxes & 7 overslded folders) Biography: Ferenc Nagy was a founder of the Hungarian Smallholders' Party, and Prime Minister of Hungary from 1946 until 1947 when he was forced to resign by the Communists. The rest of his life was spent In the United States where he was active as an author, lecturer and leader of Hungarian emigre political organizations. Arrangement: Cataloged correspondence. Box 1; Arranged Correspondence, Boxes 1-22; Arranged Lecture Correspondence, Boxes 23-35; Arranged Manuscripts. Boxes 36- 44; Subject Files, Boxes 45-74; Clippings, Boxes 75-80; Printed Materials, Boxes 81-93. Oversize Material: Subject Files; Clippings; Printed Materials. Summary: The Ferenc Nagy Papers consist of correspondence, manuscripts, subject files and printed materials relating to Nagy's career and family. The earliest materials cover the period 1945 to 1947 when Nagy was leader of the Hungarian Smallholders' Party, and later Prime Minister of Hungary. Of special interest are first-hand accounts and commentaries on the circumstances surrounding his resignation in 1947. Materials from the years 1948-1954 concern Nagy's leadership of emigre organizations Including the Hungarian National Council, the Committee for a Free Europe, the Assembly of Captive European Nations and the International Peasant Union. Correspondence files contain one letter each from presidents Harry S. Truman, Richard M. Nixon, and Jimmy Carter, also voluminous correspondence with Hungarian emigre politicians Pal Auer, Gyorgy Bessenyey, Bela Fabian, Pal Fabry, Karoly Peyer, Bela Varga and others. Nagy was much in demand as a public speaker and author and the Papers Include completed texts and drafts of many of his speeches and articles. -

UN GA Gai•! OL®GIAI ALAPKÖNYVTÁR V

UN GA GA i•! OL®GIAI ALAPKÖNYVTÁRV TÁR Könyvjegyzék Kiadja a Nemzetközi Magyar Filológiai Társaság és a Tudományos Ismeretterjesztő Társulat Budapest 1986 Hungarológiai alapkönyvtár -- HUNGAROLÓGIAI ALAPKÖNYVTÁR Könyvjegyzék Kiadja a Nemzetközi Magyar Filológiai Társaság és a Tudományos Ismeretterjesztő Társulat Budapest 1986 A bibliográfiát összeállították: Bevezető rész STAUDER MARIA közreműködésével V. WINDISCH ÉVA Nyelvtudomány D. MATAI MARIA Irodalomtudomány TÓDOR ILDIKÓ és B. HAJTÓ ZSÓFIA Néprajz KOSA LÁSZLÓ Szerkesztette NYERGES JUDIT közreműködésével V. WINDISCH ÉVA Tudományos Ismeretterjesztő Társulat Felelős kiadó: Dr.Rottler Ferenc főtitkár 86.1-199 TIT Nyomda,- -Budapest . - Formátum: A/5 - Terjedelem: 11,125 A/5 ív - Példányszám: 700 Félelős vezető: Dr.Préda Tibor TARTALOMMUTATÓ ELŐSZÓ 9 RŐVIDÍTÉSEK JEGYZÉKE 12 BEVEZETŐ RÉSZ 15 1 A magyarok és Magyarország általában 17 2 A magyar nemzeti bibliográfia 17 2.1 Hungarika-bibliográfiák 19 3 Lexikonok 19 4 Szótárak 20 5 Gyűjtemények katalógusai 21 6 Az egyes tudományterületek segéd- és kézikönyvei 22 6.1 Földrajz, demográfia 22 .6.2 Statisztika 22 6.3 Jog, jogtörténet 22 6.4 Szociológia 23 6.5 Történelem 24 6.51 Általános magyar történeti bibliográfiák, repertóriumok 24 6.511 Történeti folyóiratok repertóriumai 24 6.52 összefoglaló művek, tanulmánykötetek a teljes magyar törté- nelemből 25 6.53 A magyar történelem egyes korszakaira vonatkozó monográ- fiák, tanulmánykötetek, forrásszövegek 28 6.531 Őstörténet, középkor 28 6.532 1526-1849 29 6.533 1849-1919 29 6.534 1919-től napjainkig 30 6.54 Gazdaság- és társadalomtörténet 30 6.55 Művelődéstörténet 32 6.551 Művelődéstörténet általában. Eszmetörténet 32 6.552 Egyháztörténet 33 6.553 Oktatás- és iskolatörténet 33 6.554 Könyvtörténet 35 6.555 Sajtótörténet 35 6.556 Tudománytörténet 36 6.557 Közgyűjtemények, kulturális intézmények története 37 6.558 Életmódtörténet 37 6.56 Történeti segédtudományok. -

Download 12-Ib-History

Dr. Wannamaker IB 20th Century Welcome Back from Summer Assignment 2010+ Create 200 flashcards, minimum ten words each, “How will I use this in an essay?” method: Creah century world history—prescribed subjects • Young Turks • Spanish American War • Open Door Policy • Nicholas II • Ottoman Empire • Qing • Sphere of Influence • Roosevelt Corollary • Insurgency • Historiography • Willliam Appleman Williams • Dialectical Materialism • Sun Yat-sen • Caudillos • Big Stick • Platt Amendment • Russo-Japanese War • Russian Orthodox • Bloody Sunday (1905 Rev. event) • Mensheviks • Soviets • Proletariat • Agitprop • 1917 February/March Revolution • 1917 October Revolution (Bolshevik) • V.I. Lenin • Politiburo • Francisco “Pancho” Villa • Emiliano Zapata • Porfirio Diaz • Treaty of Brest-Litovsk • War Communism • total war • First World War (1914-8) • Balfour Declaration • propaganda • Wilson and the Fourteen Points • Paris Peace Treaties 1919-1920 • Comintern • Union of Soviet Socialist Republics • (left- and right-wing) ideology • fascism • May Fourth Movement • Establishment and impact of the mandate system • US isolationism • Weimar Republic • League of Nations: account for weakness • New Economic Policy • Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek) • Chinese Civil War (1927-37 and 1946-9) • The Long March • Good Neighbour policy • America First Committee • Five Year Plan • Leon Trotsky • principle of collective security (military/diplomatic) • Munich Agreement • Appeasement • Socialism in One Country • Spanish Civil War (1936-9), • Kuomintang (Guomintang) -

The Post-Communist Way: Negotiating a New National Identity in Hungary

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-6-2012 The Post-Communist Way: Negotiating a New National Identity in Hungary Sarah Fabian [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fabian, Sarah, "The Post-Communist Way: Negotiating a New National Identity in Hungary" (2012). Honors Scholar Theses. 664. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/664 The Post-Communist Way: Negotiating a New National Identity in Hungary Sarah Fabian Maramarosy University of Connecticut at Stamford Interdisciplinary Honors Thesis May 6, 2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment for Interdisciplinary Honors Fabian 2 Preface 8th, On Monday September 1 2006 reports of police terror in Budapest flooded the news broadcasts. Tear gas, rubber bullets and water cannons were relentlessly fired on citizens leaving hundreds injured. Wanton brutality replaced law as the police charged on peaceful protesters. Cars were overturned and aflame. A Soviet-era tank was hijacked. Masses were led away in handcuffs. The scene was all too familiar to the streets of Budapest. Yet, the year was 2006 not 1956. What had brought about this crisis in Hungary? Earlier in 2006 leaked recordings of Prime Minister Gyurcsãny of the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) admitting to the party’s fraudulent election campaign and incomplete disclosure regarding economic reforms caused a public outcry for his resignation during the 1956 anniversary. In the Lies Speech, as it is referred to today, Gyurcsány unequivocally stated: “If we have to give account to the country about what we did for four years, then what do we say? We lied in the morning, we lied in the evening.”1 Demonstration around the streets of Budapest carried on for weeks with crowds initially numbering between 2,000 to 8,000 people daily.2 Protests soon spread to the countryside and to neighboring Romania, Serbia and Austria in solidarity. -

The Hungarian „Goulash Communism” and Reforms in „Chinese Style”

How did China Learn from and Surpass the Hungarian Reform Model? An Analysis of Structural Reasons Abstract: In this paper similarities and differences are demonstrated between Chinese and Hungarian party- state systems. We define the structural background of different reforms that created the Hungarian “Goulash communism” and the reforms in “Chinese style”. We shall demonstrate how these structural backgrounds have lead to political transformation first in Hungary accompanied by economic crisis, and economic transformation first in China accompanied by macroeconomic growth. Introduction: System transformation in Eastern Europe and Soviet Union started with the political de- legitimating of the communist party. Political transformation logically drew the attention of scholars studying these regions to democratization, economic crisis and systemic outcomes 1 1 Hellman, Joel, (1998): ”Winners Take All: the Politics of Partial Reform in Post-communist Transformations” World Politics 50 (January): 203-3; Siglitz, Joseph E. 'Wither Reform? Ten Years of the Transition' Paper prepared for the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics, Washington, D.C. April 28-30, 1999; de Melo, and Gelb A., 'From Plan to Market: Patterns of Transition' Washington, DC 1996, World Bank; Hoen, Herman W. The Transformation of Economic Systems in Central Europe Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA, 1998; Gomulka, S. ’Economic and Political constraints during Transition' Europe’. Asia Studies, 1994, Vol.. 46 N. 1, pp. 89-106; Comisso, Ellen, ‘Market failures and market socialism: Economic problems of the transition’, in Eastern European Politics and Societies, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1988 pp. 433-65; Bunce, Valerie and Maria Csanádi, 'Uncertainty in the Transition. Post- Communism in Hungary' East European Politics and Society, Vol. -

KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers No

KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers No. 54 September 1998 Maturity and Tasks of Hungarian Industry in the Context of Accession to the EU Summary Report of a KOPINT-DATORG Project KOPINT-DATORG Economic Research, Marketing and Computing Co. Ltd. H-1081 Budapest, Csokonai u. 3. KOPINT-DATORG Discussion Papers Editorial Board: László Csaba András Köves (Chairman) Gábor Oblath Iván Schweitzer László Szamuely Managing Editor: Iván Schweitzer This Summary report is a result of a project launched by the Hungarian Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism (IKIM) in 1997. The section activity of the in phase I. and II. and the elaboration of the project reports was co-ordinated by the KOPINT-DATORG Co. On the details see the I. chapter of this report ("Antecedents"). The following statements reflect the standpoint of the Project's expert team. Comments are welcome. KOPINT-DATORG Economic Research, Marketing and Computing Co. Ltd. H-1081 Budapest, Csokonai u. 3. Phone: (36-1) 303-9578 Fax: (36-1) 303-9588 ISSN 1216-0725 ISBN 963 7275 59 2 Maturity and Tasks of Hungarian Industry in the Context of Accession to the EU Summary Report of a KOPINT-DATORG Project Project chairman: Szabolcs Fazakas, Ex-Minister, IKIM Project director: János Deák, Managing Director, Chairman, KOPINT-DATORG Co. Project secretaries: Ms Mogyorósy, Dr Rózsa Halász, Chief Counsellor, IKIM Dr Zsuzsa Borszéki, Division Head, KOPINT-DATORG Co. Section heads, Phase I. I. Mining Dr János Fazekas, MD, Bakony Bauxite Mines Ltd. II. Textiles, leather, footwear Dr József Cseh, GS, Hungarian Light IndustrialAssociation III. Paper Miklós Galli, MD, Chairman, Dunapack Paper and Packaging Material PLC IV. -

56 Stories Desire for Freedom and the Uncommon Courage with Which They Tried to Attain It in 56 Stories 1956

For those who bore witness to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, it had a significant and lasting influence on their lives. The stories in this book tell of their universal 56 Stories desire for freedom and the uncommon courage with which they tried to attain it in 56 Stories 1956. Fifty years after the Revolution, the Hungar- ian American Coalition and Lauer Learning 56 Stories collected these inspiring memoirs from 1956 participants through the Freedom- Fighter56.com oral history website. The eyewitness accounts of this amazing mod- Edith K. Lauer ern-day David vs. Goliath struggle provide Edith Lauer serves as Chair Emerita of the Hun- a special Hungarian-American perspective garian American Coalition, the organization she and pass on the very spirit of the Revolu- helped found in 1991. She led the Coalition’s “56 Stories” is a fascinating collection of testimonies of heroism, efforts to promote NATO expansion, and has incredible courage and sacrifice made by Hungarians who later tion of 1956 to future generations. been a strong advocate for maintaining Hun- became Americans. On the 50th anniversary we must remem- “56 Stories” contains 56 personal testimo- garian education and culture as well as the hu- ber the historical significance of the 1956 Revolution that ex- nials from ’56-ers, nine stories from rela- man rights of 2.5 million Hungarians who live posed the brutality and inhumanity of the Soviets, and led, in due tives of ’56-ers, and a collection of archival in historic national communities in countries course, to freedom for Hungary and an untold number of others. -

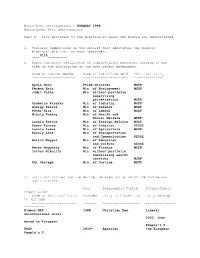

HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent

Macro-Data Questionnaire - HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the dataset that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ____V114__________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party ---------------------- ----------------------- --------------- Gyula Horn Prime Minister MSZP Ferenc Baja Min. of Environment MSZP Judit Csiha Min. without portfolio supervising privatization MSZP Szabolcs Fazakas Min. of Industry MSZP Gyorgy Keleti Min. of Defence MSZP Peter Kiss Min. of Labour MSZP Mihaly Kokeny Min. of Health and Social Welfare MSZP Laszlo Kovacs Min. of Foreign Affairs MSZP Gabor Kuncze Min. of Interior SZDSZ Laszlo Lakos Min. of Agriculture MSZP Karoly Lotz Min. of Transportation and Communication SZDSZ Balint Magyar Min. of Education and Culture SZDSZ Peter Megyessy Min. of Finance MSZP Istvan Nikolits Min. without portfolio supervising secret services MSZP Pal Vastagh Min. of Justice MSZP 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Year Ideological Family International Organization Name of Political Party Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) ----------------------- ------- ------------------- ---------------- ---------- Fidesz-MPP 1988 Christian Dem. Liberal International until 2000, then moved to European People's P. FKGP 1930* Agrarian the European People's P. suspended the FKGP's membership in 1992 KDNP 1988 Christian Dem. The European People's P. suspended the KDNP's membership in 1997 MDF 1988 Christian Dem. European People's P. -

Hi-Story Lessons

01.06.1947 Communists Take Over after Ousting Prime Minister 17 Ferenc Nagy According to popular belief, in the beginning of 1945 representatives from the world’s three superpowers convened at the Yalta Conference and decided how to .................................. redivide the globe. As a result of this decision, Hungary became a part of the .................................. Soviet satellite zone. In spite of the fact that the third world-power, Great Britain, .................................. used the few tools at its power to block the spread of communist influence in .................................. Europe, the British proved incapable of realising this goal in the face of Soviet .................................. might. The extent of how extremely eective the Soviet Union was at enforcing its .................................. interests is best shown by the fact that it was the Soviet-friendly communists, not .................................. the exiled government located in London, that came to power following the .................................. liberation of Poland. While the Paris Peace Accord signed in 1947 stipulated that .................................. all Red Army forces had to leave Hungary’s territory within ninety days, Austria’s .................................. occupation provided an excellent reason for Soviet troops to remain. Established in 1945, the Soviet-led Allied Control Commission ACC supervised Hungary’s .................................. internal as well as external aairs and consequently restricted the nation’s .................................. sovereignty to a significant degree. In spite of the fact that the United States’ foreign policy initially strove to cooperate with the Soviet Union, the relationship between the two world powers soon grew tense, resulting in the face-o of the Cold War. As of 1947, President .................................. Truman attempted to follow a new course in foreign diplomacy in an attempt to ................................. -

The Hungarian Revolution of 1989: Perspectives and Prospects for Kozotteuropa

NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS THE HUNGARIAN REVOLUTION OF 1989: PERSPECTIVES AND PROSPECTS FOR KOZOTTEUROPA by Ricky L. Keeling June 1991 Thesis Advisor: Professor Mikhail Tsypkin, Ph.D. Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited T258468 Unclassified SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1 a REPORT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION 1b RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS Unclassified 2a SECURITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 3 DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY OF REPORT Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 2b DECLASSIFICATION/DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE 4 PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 5 MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 6a. NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 6b OFFICE SYMBOL 7a NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School (// applicable) Naval Postgraduate School 55 6c ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) Monterey, CA 93943-5000 Monterey, CA 93943-5000 8a. NAME OF FUNDING/SPONSORING 8b. OFFICE SYMBOL 9 PROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IDENTIFICATION NUMBER ORGANIZATION (If applicable) 8c ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 10 SOURCE OF FUNDING NUMBERS Program Element No Project No Work Unit Accession Number 1 1 . TITLE (Include Security Classification) The Hungarian Revolution of 1989: Perspectives and Prospects for Kozotteuropa 12 PERSONAL AUTHOR(S) Ricky L. Keeling, Capt, USAF 13a. TYPE OF REPORT 13b TIME COVERED 14 DATE OF REPORT (year, month, day) 15 PAGE COUNT Master's Thesis 1991 June 20 From To aj 16 SUPPLEMENTARY NOTATION The views expressed