Proceedings of the Third Conference on Computation, Communication, Aesthetics and X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1

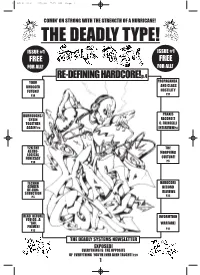

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1 COMINÕ ON STRONG WITH THE STRENGTH OF A HURRICANE! THE DEADLY TYPE! ISSUE #1 ISSUE #1 FREE FREE FOR ALL!L FOR ALL!L RE-DEFINING HARDCORE!p.4 YOUR PROPAGANDA DRUGGED AND CLASS FUTURE! HOSTILITY P.14 P.11 BURROUGHS/ PRAXIS GYSIN RECORD'S TOGETHER C. FRINGELLI AGAIN! P.6 INTERVIEWP.8 Y2K:THE THE ASTRO- MORPHING LOGICAL FORECAST CULTURE! P.10 P.5 TECHNO HARDCORE GENDER RECORD DE-CON- STRUCTION REVIEWS P.5 P.16 READ BEFORE INFORMTION YOU GO...A "JAIL WARFARE! PRIMER! P.12 P.13 THE DEADLY SYSTEMS NEWSLETTER EXPOSED! EVERYTHING IS THE OPPOSITE OF EVERYTHING YOU'VE EVER BEEN TAUGHT! P.29 1 DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 2 money. So you could say that the rave scene was truly assimilated on just about all fronts by the mainstream. This WHY THE aggravated a problem of mis-concep- tion for the music itself . Most people being introduced to Hardcore had no idea about the ideas surrounding it-or DEADLY that there even were any! To most peo- ple, even a few making music they claimed was “hardcore”, it was just fast, noizy, and supposed to piss you off. This is retarded. Nothing can be further TYPE? from the truth, and that is why “The Deadly Type” exists today, to re-define Hardcore. Firstly, “RE” as to do it again, -by Deadly Buda as people are not even aware of it’s influences, history or forgot the entire The original reason for this social context. -

Videogame Art and the Legitimation of Videogames by the Art World

Videogame Art and the Legitimation of Videogames by the Art World xCoAx 2015 Computation Communication Sofia Romualdo Aesthetics Independent researcher, Porto, Portugal and X [email protected] Glasgow Scotland Keywords: videogames, art, art world, legitimation 2015.xCoAx.org The legitimation process of a new medium as an accepted form of art is often accelerated by its adaptation by acclaimed artists. Examining the process of acceptance of popular culture, such as cinema and comic books, into the art world, we can trace histori- cal parallels between these media and videogames. In recent years, videogames have been included in exhibitions at specialty muse- ums or as design objects, but are conspicuously absent from tra- ditional art museums. Artists such as Cory Arcangel, Anne-Marie Schleiner and Feng Mengbo explore the characteristics of videog- ames in their practices, modding and adapting the medium and its culture to their needs, creating what is often called Videogame art, which is widely exhibited in art museums but often criticised within the videogames community. This paper aims to give a per- spective of Videogame art, and explore its role in the legitimation process of the videogame medium by the art world. 152 1 Introduction The assimilation of a new medium into the art world has, tradi- tionally, been a matter of contention throughout the history of art. Media such as photography, film, television, street art and comic books struggled to be recognized and respected for several years after their creation, but were eventually accepted into the network comprised of galleries, museums, biennials, festivals, auctions, critics, curators, conservators, and dealers, defined thus by art historian Robert Atkins: The art world is a professional realm – or subculture in anthropological lan- guage – akin to those signified by the terms Hollywood or Wall Street. -

Subkulturní Rysy Na Brněnské Scéně Populární Hudby. Srovnávací Studie O Publiku Popu, Techna a Metalu

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Hudební věda Martina Marešová Subkulturní rysy na brněnské scéně populární hudby. Srovnávací studie o publiku popu, techna a metalu. Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Mikuláš Bek, Ph.D. Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. ................................................................................. Podpis autora práce Na tomto místě bych chtěla poděkovat mému vedoucímu práce doc. PhDr. Mikuláši Bekovi, Ph.D. za cenné náměty a připomínky. Dále bych chtěla poděkovat i všem ostatním, kteří mi poskytli rady a pomoc. OBSAH 1 ÚVOD ...................................................................................................................................................................................................2 2 SUBKULTURA ..................................................................................................................................................................................3 2.1 Subkultury v ................................................................................................... 4 3 POP MUSIC ................................České republice................................ a brněnská................................ scéna ........................................................................................5 3.1 ........................................................................................................ 5 4 METALStručná -

Selling and Collecting Art in the Network Society

PAU | PAU WAELDER SELLING AND COLLECTING ART IN THE NETWORK SOCIETY NETWORK THE IN ART COLLECTING AND SELLING PhD Dissertation SELLING AND COLLECTING ART IN THE NETWORK SOCIETY Information and Knowledge Society INTERACTIONS Doctoral Programme AMONG Internet Interdisciplinary Institute(IN3) Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) CONTEMPORARY ART NEW MEDIA AND THE ART MARKET Pau Waelder Thesis Directors Dr. Pau Alsina Dr. Natàlia Cantó Milà PhD Dissertation SELLING AND COLLECTING ART IN THE NETWORK SOCIETY INTERACTIONS AMONG CONTEMPORARY ART, NEW MEDIA, AND THE ART MARKET PhD candidate Pau Waelder Thesis Directors Dr. Pau Alsina Dr. Natàlia Cantó Milà Thesis Committee Dr. Francesc Nuñez Mosteo Dr. Raquel Rennó Information and Knowledge Society Doctoral Programme Internet Interdisciplinary Institute(IN3) Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) Barcelona, October 19, 2015 To my brother David, who taught me what computers can do. Cover image: Promotional image of the DAD screen displaying the artwork Schwarm (2014) by Andreas Nicolas Fischer. Photo: Emin Sassi. Courtesy of DAD, the Digital Art Device, 2015. Selling and collecting art in the network society. Interactions among contemporary art, new media and the art market by Pau Waelder is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The present dissertation stems from my professional experience as art critic and curator, Sassoon, Shu-Lea Cheang, Lynn Hershmann-Leeson, Philippe Riss, Magdalena Sawon as well as my research in the context of the Information and Knowledge Society Doctoral and Tamas Banovich, Kelani Nichole, Jereme Mongeon, Thierry Fournier, Nick D’Arcy- Programme at the Internet Interdisciplinary Institute (IN3) – Universitat Oberta de Fox, Clara Boj and Diego Díaz, Varvara Guljajeva and Mar Canet, along with all the artists Catalunya. -

Rave-Culture-And-Thatcherism-Sam

Altered Perspectives: UK Rave Culture, Thatcherite Hegemony and the BBC Sam Bradpiece, University of Bristol Image 1: Boys Own Magazine (London), Spring 1988 1 Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………...……… 7 Chapter 1. The Rave as a Counter-Hegemonic Force: The Spatial Element…….…………….13 Chapter 2. The Rave as a Counter Hegemonic Force: Confirmation and Critique..…..…… 20 Chapter 3. The BBC and the Rave: An Agent of Moral Panic……………………………………..… 29 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 37 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 39 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 50 2 ‘You cannot break it! The bonding between the ravers is too strong! The police and councils will never tear us apart.’ In-ter-dance Magazine1 1 ‘Letters’, In-Ter-Dance (Worthing), Jul. 1993. 3 Introduction Rave culture arrived in Britain in the late 1980s, almost a decade into the premiership of Margaret Thatcher, and reached its zenith in the mid 1990s. Although academics contest the definition of the term 'rave’, Sheila Henderson’s characterization encapsulates the basic formula. She describes raves as having ‘larger than average venues’, ‘music with 120 beats per minute or more’, ‘ubiquitous drug use’, ‘distinctive dress codes’ and ‘extensive special effects’.2 Another significant ‘defining’ feature of the rave subculture was widespread consumption of the drug methylenedioxyphenethylamine (MDMA), otherwise known as Ecstasy.3 In 1996, the government suggested that over one million Ecstasy tablets were consumed every week.4 Nicholas Saunders claims that at the peak of the drug’s popularity, 10% of 16-25 year olds regularly consumed Ecstasy.5 The mass media has been instrumental in shaping popular understanding of this recent phenomenon. The ideological dominance of Thatcherism, in the 1980s and early 1990s, was reflected in the one-sided discourse presented by the British mass media. -

A Real Love Story Camila Batmanghelidjh, Founder of Kids Company, Talks About Neuroplasticity

MUSE.09/10/12 A Real Love Story Camila Batmanghelidjh, founder of Kids Company, talks about neuroplasticity The Pride of the North How Gay Pride in York is changing perceptions Freshers’ Week 1964 What the crazy kids of York were up to in the Sixties M2 www.ey.com/uk/careers 09/10/12 Muse. M10 M12 M22 Features. Arts. Film. M4. Flamboyant psychotherapist Camila Bat- M18. Mary O’Connor speaks to poet and rap- M22. James Tyas interviews Sally El Hosaini, manghelidjh speaks to Sophie Rose Walker per Kate Tempest about love and we look back Director of My Brother the Devil, premiering at about the work of her charity Kids Company. at the legacy of Gustav Klimt. the BFI’s London Film Festival this October. M6. What is the frankly rather cool history of Freshers at York? Bella Foxwell investigates Fashion. Food & Drink. what’s changed and what hasn’t. M16. Ben Burns interviews fashion illustra- M23. Ward off Freshers Flu with Hana Teraie- M8. Gay Pride is out and thriving in York. tor Richard Kilroy, Miranda Larbi goes crazy for Wood’s delicous Ratatouille and Irish Coffee. Stefan Roberts and Tom Witherow looks at jacquard, and the ‘Whip-ma-Whop-ma’ shoot on Plus our review of Jamie Oliver’s new restaurant. the Northern scene’s dynamic. M12. M10. Young girls in Sri Lanka are prime Music. Image Credits. targets for terrorism training. Laura Hughes investigates why. M20. Death-blues duo Wet Nuns talk to Ally Cover: Kate Treadwell, Kids Company Swadling about facial hair, and there are stories Photoshoot: All photos credit to the marvellous from Pale Seas. -

Artistic Approaches to Sound, Technology and Field Recording

Listening Through Making: Artistic approaches to sound, technology and field recording. Tim Shaw | Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts and Cultures | June 2019 1 Abstract This thesis draws on notions of ‘thinking through making’ to consider how the act of field recording reveals new ways of thinking about how technology shapes sonic experience. Within sound art practice, evidence of the act of making audio recordings is commonly removed from or aesthetically neglected in the context of public presentation or performance; sound recordist and recording technology are made invisible to the audience. Rather than concealing the act of recording, the artistic projects presented in this thesis explore methods for engaging publics in the practical activity and particular material qualities of field recording. Three artworks are presented that employ and examine field recording practices; a musical performance (Fields, 2014-2018), a sound walk (Ambulation, 2015-2018) and a sound installation (Ring Network, 2016-2018). Particular elements of the making processes, the technical materials employed, publicly manifested artworks and critical reflection thereon are shared alongside a supporting portfolio of documentation and presentation details (this can be found in the appendices and accompanying USB storage device). The written component of this PhD submission offers an additional access point into this body of work and is designed to accompany rather than stand in for the practice itself. The artworks presented in the thesis were developed in relation to a programme of ‘experiments’ conducted within a number of different cultural institutions. The thesis defines these experiments as an artistic and research methodology, and describes how the process allowed for multiple lines of enquiry and numerous artistic outcomes to be explored in relation to specific thematic, material and contextual concerns relating to sound and technology. -

Download” As They Are Whisked Away Into a Multidimensional Realm That Cameras Cannot Go

ALTAR STATES: SPIRIT WORLDS AND TRANSFORMATIONAL EXPERIENCES ____________ A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Science ____________ by © Peter Treagan 2019 Summer 2019 ALTAR STATES: SPIRIT WORLDS AND TRANSFORMATIONAL EXPERIENCES A Project by Peter Treagan Summer 2019 APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES: _________________________________ Sharon Barrios, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: _________________________________ _________________________________ Eugenie Rovai, Ph.D. Sarah Pike, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Celeste Jones, Ph.D. _________________________________ Randy Larsen, Ph.D. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this project may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the future ancestors living in harmony with Nature. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am forever grateful for my committee and family; your endless patience and support made all of this possible. Many thanks to the Idea Fab Labs for providing 24- hour access to the facility, training with the high-tech tools, and the creative space for unexpected collaborations throughout the process. Thank you to the MFA Gallery and Museum of Anthropology at CSU Chico for the opportunity to exhibit my work to the public and making the vision a reality. Special thanks to the talented musicians who contributed original compositions to the Altar States soundscape: Chelu de la Isla, The Sámi Brothers, Flow State, GeOMetrae, Anahata Sacred Sound Current, Puka, and Shimshai & Susana. For the inspiration and encouragement to create and share this artwork, infinite thanks to Chances R Good, Makhno Mata, Alfredo Zagaceta, Juan Carlos Taminchi, Michael Divine, and Alex & Allyson Grey. -

Musikfestivals in Niedersachsen Impressum

Musikfestivals in Niedersachsen Impressum Musikfestivals in Niedersachsen Herausgeber: Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kultur Leibnizufer 9 30169 Hannover www.mwk.niedersachsen.de Autoren: kulturNetz Christian Zech Christian Lorenz Hasselwerder Straße 116 21129 Hamburg 040 - 745274 - 14 [email protected] Redaktion und Gestaltung: Christian Zech Lektorat: Dr. Cornelia Göksu Redaktionelle Mitarbeit: Sebastian Matthes (KONO Büro für Mediales) Andreas Brüning Druck: Pusch / Buxtehude Eine ausführliche Version der Studie ist im Niedersächsischen Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kultur hinterlegt und kann auf Anfrage eingesehen werden. Stand: November 2002 Inhalt Vorwort 4 1. Vorbemerkungen 5 2. Klärung und Bestandsaufnahme: Zum Begriff Musikfestival 6 Abgrenzung des Untersuchungsgegen- standes – berücksichtigte Grenzfälle 7 Alphabetische Festivalliste 9 3. Kennzahlen 10 4. Sparteneinteilung 11 Themen 12 Zur Geschichte der Festivals 13 5. Organisation 14 6. Veranstaltungorte 15 7. Publikum 16 Zielgruppe 16 Besucherzahlen und Platzauslastung 17 Herkunft 18 Demografie 18 8. Finanzierung 19 Gesamtbudgets 19 Ausgaben 19 Einnahmen 20 Kartenpreise und Preisentwicklung 22 9. Marketing und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit 23 Kommunikationswege 23 Kartenvertrieb 24 Medienresonanz 24 10. Ausblick 25 11. Zusammenfassung 27 12. Fazit und Empfehlungen 28 Anhang: Einzeldarstellungen der Festivals 30 3 Vorwort Niedersachsen verfügt über eine vielseitige, bürgerschaft- lich geprägte und sehr lebendige Musiklandschaft. Einen Ausschnitt daraus bilden die Musikfestivals im Land, die im Rahmen dieser Studie erstmals in den Blick einer wis- senschaftlichen Bestandsaufnahme gelangen. Und die Ergebnisse sind eindrucksvoll: Mit über 100 Festivals liegt die Gesamtzahl weit über dem, was selbst Fachleute vermutet hätten. Die Studie enthält darüber hinaus zahlreiche weitere Kennzahlen, Bewertungen und Empfehlungen und wird somit zu einer unverzichtbaren Arbeitsgrundlage für viele Menschen und Institutionen, die in diesem Bereich tätig sind. -

Etoy.HISTORY

www.missioneternity.org www.etoy.com etoy.HISTORY 1994/95 An architect, a lawyer, a media designer, two musicians, and two programmers from the United States, Swtizerland, England, Italy, Los Angeles, Vienna, Zurich, Monza and Prague launched the digital art brand “etoy”. The etoy.BRAND is intended to take the place of the individual artist. The aggressive marketing and corporate identity concept as well as the dress code of etoy.AGENTS emphasizes the fact that the company, in spite of its exaggerated consumer aesthetic, produces no tangible products. The internet domain “etoy.com” is the group’s communications hub, studio, office, marketing platform, stage and archive. 1996/97 In the wake of marketing problems, the expected number of visitors to www.etoy.com was by far too low, etoy invested all available resources into researching the Internet traffic and developed its own code-based hype-machine. In the summer of 1996 etoy’s “digital hijack” - the automated kidnapping of 1.5 million internet users - achieved a breakthrough on the web. With the playful abduction of 2% of the internet population of that time, and the website www.hijack.org which tells the story of the “hijack”, etoy dramatized one of the most important phenomena of the information age: the search engines and their, until then, largely unknown methodology. The project garnered etoy the “Golden Nica” of the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz as well as other international prizes. 1998 etoy refused to adopt the image of internet pirates in order to develop in novel directions. In the context of their USA-expansion (Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco) etoy developed the following elements: etoy.TIMEZONE, etoy.SHARE and the etoy.TANKS. -

Spiritual Technologies and Altering Consciousness in Contemporary Counterculture* Graham St John

CHAPTER 10 Spiritual Technologies and Altering Consciousness in Contemporary Counterculture* Graham St John Introduction With a focus on virtual reality, techno-rave culture, and “psychedelic trance,” this chapter explores practices of consciousness alteration within contemporary countercultures. By contemporary, I mean the period from the 1960s to the present, with the chapter addressing the continuing leg- acy of earlier quests for consciousness expansion. Central to the discus- sion is the development and application of spiritual technologies (cyber, digital, and chemical) and the appeal of traditional cultures in the lifestyles of those sometimes referred to as “modern primitives.” I also pay attention to specific individuals, “techno-tribes,” cultural formations and events heir to and at the intersection of these developments, with special observations drawn from the Boom Festival—Portugal’s carnival of consciousness. Fur- thermore, the chapter considers the prevalence of DiY consciousness echoed in practices of modern shamanism. As the contiguity between altering consciousness and altering culture is explored, the chapter considers the psychological and political dimensions of that which has been variously held as “consciousness” among spokespersons and participants within visionary-, arts-, and techno-cultures. *Portions of this chapter are adapted from “Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival” by Graham St John. Published in Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture,1(1), 35–64, 2009. 204 Altering Consciousness Psychedelic Experience and Consciousness It is necessary to begin with a discussion of the 1960s countercultural milieu, whose quest for and techniques of experience are a continuing leg- acy found in the conditions of ecstatic embodiment and visionary mind- states charted in this chapter. -

Underground Club Spaces and Interactive Performance

Underground Club Spaces and Interactive Performance: How might underground club spaces be read and developed as new environments for democratic/participatory/interactive performance and how are these performative spaces of play created, navigated and utilised by those who inhabit them? Kathleen Alice O‟Grady Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Performance and Cultural Industries December 2009 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to my parents who have always believed in me and to my daughter, Maisie, who is my source of inspiration and joy. Gratitude goes to my PhD supervisors Professor Mick Wallis and Dr Martin Crick, both of whom have given me continued support and guidance throughout this research. Thanks also to my colleagues and my students at the School of Performance and Cultural Industries who have encouraged me and kept me going with their sense of humour, wise words and loyalty. Thank you to all the club and festival organizers that have allowed me access to their events, particularly those involved with Planet Angel, Synergy, Duckie, Riff Raff, Planet Zogg, Speedqueen, Manumission, Shamania, Beatherder, Nozstock and Solfest. Special gratitude to Fatmoon Psychedelic Playgrounds for allowing me the room to move creatively and to develop this practice in a supportive environment.