Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin John Iriks

The Rotary Club of Kwinana District 9465 Western Australia Chartered: 22 April 1971 Team 2020-21 President Bulletin John Iriks No 10 07th Sept. 2020 Secretary Brian McCallum President John Rotary Club of Kwinana is in its 50th year 1971/2021 Treasurer Stephen Castelli Good meeting tonight, Guest speaker Russell Cox from the City of Kwinana talking on the Kwinana Loop trail, a 21km circuit around the perimeter of the city, pleasing that it takes in the Rotary Wildflower Reserve as part of the layout. Facts & Figures Trialling our PA set-up the last couple of weeks, it’s becoming evident that the use of lapel microphones will be the way to go, primarily for our President and Attendance this week guest speakers, hand held mic’s just don’t cut it for a guest speaker. Total Members 28 We are purchasing a second lapel mic, it’s a learning curve optimising the Apologies 6 equipment we have, huge difference in cost, $4.3k to so far $180 inc. 2nd lapel. Make -up 1 Attended 21 Looking for a suitable local venue for our 50 year celebration bash, older Hon . Member 1 LOA members will recall we held our 25th at Alcoa Social Club, our 30th at Casuarina Guests 1 Hall and our 40 th at the then brand new Kelly Pavilion on Thomas Oval. Visitors Partners Special congratulations to Genevieve and Damian 74.0% on their 20th wedding anniversary celebrated on the 9th September, I suppose I should also add that Gladys and I reach our 56th on the 12th Stay safe. -

A Manual of Electricity, Magnetism, and Meteorology

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES | 34.33 ||||| O691091 – !! !! !! !! ! 2 _- - * - _º º 4.WN iſ A. N. U A ſ, _-_ — of -- … – ( Z.Z.º. cºlºſ Cſºlº, Ayſal & AyA.T.ſ. 5 ºf – ~ - an or sº w - -- > __ anº's ( // E *ſ'. E. O.A.: O I, O & Y. - - º Az _º_*zº, _{Z ~4–. _4% • *. %2. zz & C//4///:3' W. W.4/, /ſ/.../º, SºCſ. ET4/ºr 7, 17//, //, //7/2/, //, 5, , , ,77. //, /wo ºrºzzes *A ºl. II. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - --- - Tonoon: . * ~ * - - - - - - - - - - - ------ - -> --> * > *.*.*.*, *, * * x - M.A is . .” - P. i. i* - lº Hº -- - - - - - - -- - - - - * ~ * - - - - 2. - THE NEW YORK PUBLIC UIBRARY Astor, ‘f Nox TIL CEN FOUND A TY ONº. *- **º----- ADVERTISEMENT, IN presenting this volume to the public, it is only just to the publishers for me to state, that the long interval which has elapsed between the appearance of the first and the second volumes has arisen from causes over which they had no control. Circum stances having rendered it necessary for them to seek assistance to complete the volume, I was in duced, at their request, to undertake it: and all that Dr. Lardner had contributed was forthwith placed in my hands. It is unnecessary for me to state the difficulties which an author must encounter in attempting to complete a work commenced by another. I must, however, mention that, after a careful examination of the materials placed at my disposal, I have en deavoured to carry out Dr. -

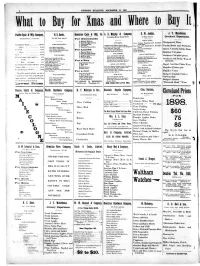

What to Buy Lor Mas and Where to My I

V f" - t ' AM&t, ' - iv' 'vTw TT' "" PVj.$ 'fiSf' rrt'fr l;"". , ;' EVENING BULLETIN, DECEMBER 18 1807. What to Buy lor Mas and Where to My I " & E. W, Jordan J. T. Waterhouse, Pacific Cycle & Mfg. Company, N. S, Sachs Hawaiian Cycle & Mfg, Co, A, E. Mnrphy Company, Arlington lllock, Hotel .Street. 10 Fort Street. Orookory Department. Km. kin Iti.iio., KoiitKt. No. 520 Fort Street. For Oentlemen KOlt A LADY: A Hawaii Wcycle "NYtiro A Search Light Lamp FOIt MKN: Kino Leather Shopping and llandkur-ehlo- f "Wedgowood llemlngtou Dlrylc SSiOO FOWOKNTLKMKN: A Punching Hag Iligs A Sweater Congress and Oxford Ijieed Shoes Kmhrohlorcd llandker- Uiists Kangaroo ltenl I.aoo and I'uriun and Statuettes " Dny's " l")00 I'lnoSllkUinbiclhs A Peerless Typewriter. In Kroneh Patont Leather and ehiefs Ilandsouio Silk Scarfs II.t f'uir milt Vnnl Calf Silk Dress and Trimmings Queen Vietoriu. Jubilee Ore-ce- nt " 75 00 ' Homcos Busts Uox of I'ino Handkerchiefs For Ladies lllaek and Colored Work liaskets Uox SlipjHirs, lllaek and Colored. SeKsors, Out-glu- ' Hoy's " 50 (X) of Silk Socks. A Hawaii IJIdyela Cases of Ruinb(w ss A Search Light Lamp FOIt LADI1: " " 4o (K) KOIl AOKNTLKMAN: aiton VOll LADIIX: A Veader Cyelometer Cut-gla- ss A Dlcyelc Hell liuii and llutton Oxfoids Ordinnry pieces .Dloyele I.aiup (extra quality)... 5 00 French Kid, Dongola Kid leather Dressing Cases Ileal IjHcu Handkerchiefs A Tennis Dacket. ' Whlto and Urown Canvas lloinstltehetl Ilandkorchlefs Crockery and China " Saddle " " ... "00 IIiukIhoiiio Ulack Idico Sc.ufs Cloth Top Smoking Cap. Ware of a. -

The Triumphs, Tributes and Trials of Treasure Hunter Tommy Thompson

Barry University School of Law Digital Commons @ Barry Law Faculty Scholarship 2016 A Crackerjack of a Sea Yarn: The rT iumphs, Tributes and Trials of Treasure Hunter Tommy Thompson Taylor Simpson-Wood Barry University Follow this and additional works at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/facultyscholarship Part of the Admiralty Commons, Civil Procedure Commons, Common Law Commons, Courts Commons, Cultural Heritage Law Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Taylor Simpson-Wood, A Crackerjack of a Sea Yarn: The rT iumphs, Tributes and Trials of Treasure Hunter Tommy Thompson, 29 U.S.F. Mar. L.J. 197 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Barry Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Barry Law. A Crackerjack of a Sea Yam: The Triumphs, Tributes and Trials of Treasure Hunter Tommy Thompson TAYLOR SIMPSON-Woon* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 198 II. THE PROLOGUE: THE TRAGIC SINKING OF THE SS CENTRAL AMERICA ............................................................................. 200 III. THE TRIUMPHS, TRIBUTES AND TRIALS OF TOMMY THOMPSON ............................................................................. 204 A. The Early Years .............................................................. 204 B. From College Student to Conquering Hero .................... 205 C. Relevant Law from the Perspective -

Fashion Through the Ages

Fashion Through The Ages • In the Victorian era, both boys and girls wore dressed until the age of around 5 years old. • High-heeled shoes were worn from the 17th century, and were initially designed for men. • Women often wore platform shoes in the 15th to 17th centuries, which kept their skirts up above the muddy streets. • Wearing purple clothes has been associated with royalty since the Roman era. The dye to make clothes purple, made from snail shells, was very expensive. • Napoleon was said to have had buttons sewn onto the sleeves of military jackets. He hoped that they would stop soldiers wiping their noses on their sleeves! • Vikings wore tunics and caps, but they never wore helmets with horns. • See the objects in the Museum collections all about looking good: http:// heritage.warwickshire.gov.uk/museum-service/collections/looking-good/ • View the history of fashion from key items in the collection at Bath’s Fashion Museum: https://www.fashionmuseum.co.uk/galleries/history- fashion-100-objects-gallery • Google’s ‘We Wear Culture’ project includes videos on the stories behind clothes: https://artsandculture.google.com/project/fashion • Jewellery has been key to fashion for thousands of years. See some collection highlights at the V&A website: https://www.vam.ac.uk/ collections/jewellery#objects A Candy Stripe Friendship Bracelet Before you begin you need to pick 4 – 6 colours of thread (or wool) and cut lengths of each at least as long as your forearm. The more pieces of thread you use, the wider the bracelet will be, but the longer it will take. -

Harry Bass; Gilded Age

Th e Gilded Age Collection of United States $20 Double Eagles August 6, 2014 Rosemont, Illinois Donald E. Stephens Convention Center An Offi cial Auction of the ANA World’s Fair of Money Stack’s Bowers Galleries Upcoming Auction Schedule Coins and Currency Date Auction Consignment Deadline Continuous Stack’s Bowers Galleries Weekly Internet Auctions Continuous Closing Every Sunday August 18-20, 2014 Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio – World Coins & Paper Money Request a Catalog Hong Kong Auction of Chinese and Asian Coins & Currency Hong Kong October 7-11, 2014 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins August 25, 2014 Our 79th Anniversary Sale: An Ocial Auction of the PNG New York Invitational New York, NY October 29-November 1, 2014 Stack’s Bowers Galleries –World Coins & Paper Money August 25, 2014 Ocial Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD October 29-November 1, 2014 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency September 8, 2014 Ocial Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD January 9-10, 2015 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – World Coins & Paper Money November 1, 2014 An Ocial Auction of the NYINC New York, NY January 28-30, 2015 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins November 26, 2014 Americana Sale New York, NY March 3-7, 2015 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency January 26, 2015 Ocial Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD April 2015 Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio – World Coins & Paper Money January 2015 Hong Kong Auction of Chinese and Asian Coins & Currency Hong Kong June 3-5, 2015 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

Singer Manufacturing Company Records 2526

Singer Manufacturing Company Records 2526 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Singer Manufacturing Company Records 2526 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Correspondence ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Agents/Dealers ............................................................................................................................................ -

Maryland Historical Magazine Patricia Dockman Anderson, Editor Matthew Hetrick, Associate Editor Christopher T

Friends of the Press of the Maryland Historical Society The Maryland Historical Society (MdHS) is committed to publishing the fnest new work on Maryland history. In late 2005, the Publications Committee, with the advice and support of the development staf, launched the Friends of the Press, an efort dedicated to raising money used solely for bringing new titles into print. Response has been enthusiastic and generous and we thank you. Our most recent Friends of the Press title, the much-anticipated Betsy Bonaparte has just been released. Your support also allowed us to publish Combat Correspondents: Baltimore Sun Correspondents in World War II and Chesapeake Ferries: A Waterborne Tradition, 1632–2000, welcome complements to the Mary- land Historical Society’s already fne list of publications. Additional stories await your support. We invite you to become a supporter, to follow the path frst laid out with the society’s founding in 1844. Help us fll in the unknown pages of Maryland’s past for future generations. Become, quite literally, an important part of Maryland history. If you would like to make a tax-deductible gif to the Friends of the Press, please direct your gif to Development, Maryland Historical Society, 201 W. Monument Street, Baltimore, MD, 21201. For additional information on MdHS publications, contact Patricia Dockman Anderson, Editor, 410-685-3750 x317, or [email protected]. Maryland Historical Society Founded 1844 Ofcers Robert R. Neall, Chairman Louise Lake Hayman, Vice President Alex. G. Fisher, Vice Chairman Frederick M. Hudson, Vice President Burton K. Kummerow, President Jayne H. Plank, Vice President James W. -

Wthm Newsletter

Windham Textile & History Museum The Mill Museum June, 2021 As Ye Sew Usually when people think of the inventor of the sewing machine, the name "Elias Howe" pops into mind. But long before Howe patented his design, Charles Weisenthal, a German, was issued a British patent in 1755 for a "needle that is designed for a machine." Unfortunately, neither an illustration, nor a model of this invention survived. In 1790 a patent for a hand-cranked machine was granted to Englishman William Saint, but there is no proof that it was ever used. Then in 1830, Barthélemy Thimonnier, a French tailor, opened the first machine-based clothing manufacturing company to make uniforms for the French army. But there was one drawback - the other local tailors were so afraid that Thimonnier would undercut their trade that they torched his factory - WITH HIM INSIDE! Fortunately, he survived. Perhaps that is why an American, Walter Hunt, didn't patent his design in 1834. He said he was afraid it would lead to massive unemployment. Enter Elias Howe in 1845. After an unsuccessful marketing trip to England, he returned to the States to find that Isaac Merritt Singer had copped his design. Howe sued Singer for Patent Infringement and won. After the dust settled, both men ended up millionaires, and home and commercial sewing were revolutionized. Soon, many other companies entered the market. Sewing machines were one of the first mass- market complex consumer goods distributed around the globe. By 1920 they were nearly everywhere - in cities, towns, and tiny hamlets. There's even a memorable scene in Fiddler on the Roof in which Motel has his new machine blessed by the village of Anatevka's rebbe. -

Kwaggasrand School Year 2 English: First Additional Language Week 4 Term 2 Dear Year 2 Learner, This Document Contains the Work for Week 4 Term 2

Kwaggasrand School Year 2 English: First Additional Language Week 4 Term 2 Dear Year 2 learner, This document contains the work for Week 4 Term 2. The work consists of 4 sections namely: 1. Listening and Speaking 2. Reading and Viewing 3. Writing and Presenting 4. Language Structure and Conventions Remember the following: Complete all the activities/answers in a separate book or on a sheet of paper. Write the heading, week and date for every activity you do e.g. Listening and Speaking Week 4 4 May 2020 Your parents/guardians are allowed to help and guide you should you struggle, but you need to complete the work yourself. Please bring along all completed work when the school reopens again. Good luck and just try your best! Stay safe! Regards Ms. Z. Esterhuyse 1 Kwaggasrand School Year 2 English: First Additional Language Week 4 Term 2 Listening and Speaking Discuss the invention of sewing machines with a parent/guardian. Understand and use new vocabulary (page 4) Answer questions orally (page 4) Sewing machine, any of various machines for stitching material (such as cloth or leather), usually having a needle and shuttle to carry thread and powered by treadle, waterpower, or electricity. It was the first widely distributed mechanical home appliance and has been an important industrial machine. Detail of contemporary sewing machine parts: needle, needle bar, presser foot, feed dog, bobbin case, shuttle (loop taker), machine bed, and plate. An early sewing machine was designed and manufactured by BarthélemyThimonnier of France, who received a patent for it by the French government in 1830, to mass-produce uniforms for the French army, but some 200 rioting tailors, who feared that the invention would ruin their businesses, destroyed the machines in 1831. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000