Exploring the Relevance of Manual Pattern Cutting Skills in a Technological Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design by the Yard; Textile Printing from 800 to 1956

INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI_NVINOSHilWS S3 I a Vy a n_LI BRAR I ES SMITHS0N1AN_INSTITIJ S3iyvMan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiws S3iyv S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiJ-SNi nvinoshiiws saiav l"'lNSTITUTION^NOIinillSNl"'NVINOSHiIWS S3 I MVy 8 ll'^LI B RAR I ES SMITHSONIAN INSTITI r- Z r- > Z r- z J_ ^__ "LIBRARIES Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiws S3IMV rs3 1 yvy an '5/ o ^INSTITUTION N0IiniliSNI_NVIN0SHilWS"S3 I H VM 8 IT^^LI B RAR I ES SMITHSONIANJNSTITl rS3iyvyan"LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHIIWS S3iav ^"institution NOIiniliSNI NviNOSHiiws S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian instit 9'^S3iyvaan^LIBRARIEs'^SMITHS0NlAN INSTITUTION NOIifliliSNI NVINOSHilWs'^Sa ia\i IVA5>!> W MITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS S3ldVyan LI B R AR I ES SMITHSONI; Z > </> Z M Z ••, ^ ^ IVINOSHilWs'^S3iaVaan2LIBRARIES"'SMITHSONlAN2lNSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI_NVINOSHill JMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS S3IMVHan LIBRARIES SMITHSONI jviNOSHiiws S3iavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiifiiiiSNi nvinoshii I ES SMITHSONI MITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIifliliSNI NVIN0SHilWS"'S3 I ava a n~LI B RAR < |pc 351 r; iJt ^11 < V JVIN0SHilWS^S3iavaan~'LIBRARIES^SMITHS0NIAN"'lNSTITUTI0N NOIiniliSNI^NVINOSHil — w ^ M := "' JMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS S3iavaan LI B RAR I ES SMITHSONI ^^ Q X ' "^ — -«^ <n - ^ tn Z CO wiNOSHiiws S3iavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi_NviNOSHii _l Z _l 2 -• ^ SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS SSiavaail LIBRARIES SMITHSON NVINOSHilWS S3iavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiisNi nvinoshi t'' 2 .... W 2 v^- Z <^^^x E . ^ ^-^ /Si«w*t DESIGN BY THE YARD TEXTILE PRINTING FROM 800 TO 1956 THE COOPER UNION MUSEUM FOR THE ARTS OF DECORATION NEW YORK ACKNOWLEDGMENT In assembling material for the exhibition, the Museum has received most helpful suggestions and information from the following, to whom are given most grateful thanks: Norman Berkowitz John A. -

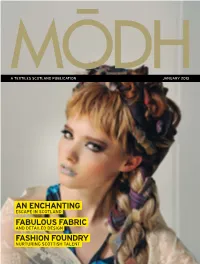

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

Bulletin John Iriks

The Rotary Club of Kwinana District 9465 Western Australia Chartered: 22 April 1971 Team 2020-21 President Bulletin John Iriks No 10 07th Sept. 2020 Secretary Brian McCallum President John Rotary Club of Kwinana is in its 50th year 1971/2021 Treasurer Stephen Castelli Good meeting tonight, Guest speaker Russell Cox from the City of Kwinana talking on the Kwinana Loop trail, a 21km circuit around the perimeter of the city, pleasing that it takes in the Rotary Wildflower Reserve as part of the layout. Facts & Figures Trialling our PA set-up the last couple of weeks, it’s becoming evident that the use of lapel microphones will be the way to go, primarily for our President and Attendance this week guest speakers, hand held mic’s just don’t cut it for a guest speaker. Total Members 28 We are purchasing a second lapel mic, it’s a learning curve optimising the Apologies 6 equipment we have, huge difference in cost, $4.3k to so far $180 inc. 2nd lapel. Make -up 1 Attended 21 Looking for a suitable local venue for our 50 year celebration bash, older Hon . Member 1 LOA members will recall we held our 25th at Alcoa Social Club, our 30th at Casuarina Guests 1 Hall and our 40 th at the then brand new Kelly Pavilion on Thomas Oval. Visitors Partners Special congratulations to Genevieve and Damian 74.0% on their 20th wedding anniversary celebrated on the 9th September, I suppose I should also add that Gladys and I reach our 56th on the 12th Stay safe. -

How Is Chintz Made and Where Does It Originate? Where Is It Commonly

How is chintz 1. It is a closely woven, lustrous, plain weave cotton fabric, printed or made and where plain, that has been glazed with starch or glue and then friction does it originate? calendered. Much used for curtains and upholstery. Where is it 2. It was originally a painted or stained calico produced in India and commonly used? popular for bed covers, quilts and draperies, popular in Europe in 17th century and 18th century, where it was imported and later produced. Europeans at first produced reproductions of Indian designs, and later added original patterns. 3. A well-known make was toile de Jouy, which was manufactured in Jouy, France between 1700 and 1843. Today it usually consists of bright patterns printed on a light background. Which weave is used 1. It is a rich fabric using the Jacquard weave where an all over to produce Brocade, interwoven design usually floral patterns. and where is it used? 2. It is used for upholstery and other interior products and often incorporates gold, silver or other metallic yarns. 3. It is also used in Chinese garments. 4. Brocade is typically woven on a draw loom. It is a supplementary weft technique, that is, the ornamental brocading is produced by a supplementary, non-structural, weft in addition to the standard weft that holds the warp threads together. The purpose of this is to give the appearance that the weave actually was embroidered on. How are chenille yarns 1. The weft yarn is manufactured by placing short lengths of yarn, called made and how are they the "pile", between two "core yarns" and then twisting the yarn used? together. -

Henri Matisse, Textile Artist by Susanna Marie Kuehl

HENRI MATISSE, TEXTILE ARTIST COSTUMES DESIGNED FOR THE BALLETS RUSSES PRODUCTION OF LE CHANT DU ROSSIGNOL, 1919–1920 Susanna Marie Kuehl Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2011 ©2011 Susanna Marie Kuehl All Rights Reserved To Marie Muelle and the anonymous fabricators of Le Chant du Rossignol TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements . ii List of Figures . iv Chapter One: Introduction: The Costumes as Matisse’s ‘Best Spokesman . 1 Chapter Two: Where Matisse’s Art Meets Textiles, Dance, Music, and Theater . 15 Chapter Three: Expression through Color, Movement in a Line, and Abstraction as Decoration . 41 Chapter Four: Matisse’s Interpretation of the Orient . 65 Chapter Five: Conclusion: The Textile Continuum . 92 Appendices . 106 Notes . 113 Bibliography . 134 Figures . 142 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As in all scholarly projects, it is the work of not just one person, but the support of many. Just as Matisse created alongside Diaghilev, Stravinsky, Massine, and Muelle, there are numerous players that contributed to this thesis. First and foremost, I want to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Heidi Näsström Evans for her continual commitment to this project and her knowledgeable guidance from its conception to completion. Julia Burke, Textile Conservator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, was instrumental to gaining not only access to the costumes for observation and photography, but her energetic devotion and expertise in the subject of textiles within the realm of fine arts served as an immeasurable inspiration. -

Singer Manufacturing Company Records 2526

Singer Manufacturing Company Records 2526 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Singer Manufacturing Company Records 2526 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Correspondence ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Agents/Dealers ............................................................................................................................................ -

Toile: the Storied Fabrics of Eure and America Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TOILE: THE STORIED FABRICS OF EURE AND AMERICA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michele Palmer | 176 pages | 01 Oct 2003 | Schiffer Publishing Ltd | 9780764318917 | English | Atglen, United States Toile: The Storied Fabrics of Eure and America PDF Book Many American women made warm and attractive quilts to benefit U. Only 27 left in stock - order soon. Hilary Farr Loxodonta Linen Caribe. A useful resource section lists specialized antique toile dealers, books, fabric companies, museums, and retailers with phone numbers and website contacts. Heater Fuel Filter F 4. Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. Waverly Charmed Life Toile Cornflower. With it's unique scenic design, pattern, color and texture, toile material is often used to highlight and contrast the overall interior design. Iron Trails of North America: The decade of the s, like the s, was one of extremes. Through his striking photography, Eric Holubow provides a glimpse inside these perilous structures to reveal the slow but unforgiving wear and tear that has befallen Only 46 left in stock - order soon. Pause slideshow Play slideshow. Only 14 left in stock - order soon. Item Name-. Over designs and colours of European Fabrics to choose from. Wilmington Seeds of Gratitude Toile Tan. Although not a weapon in the traditional sense of the word, arguably no item in Only 7 left in stock - order soon. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Coverlets and the Spirit of America. Toile: The Storied Fabrics of Eure and America Writer Only 35 left in stock - order soon. Warehouse at Ubi Techpark We had just moved. -

Wthm Newsletter

Windham Textile & History Museum The Mill Museum June, 2021 As Ye Sew Usually when people think of the inventor of the sewing machine, the name "Elias Howe" pops into mind. But long before Howe patented his design, Charles Weisenthal, a German, was issued a British patent in 1755 for a "needle that is designed for a machine." Unfortunately, neither an illustration, nor a model of this invention survived. In 1790 a patent for a hand-cranked machine was granted to Englishman William Saint, but there is no proof that it was ever used. Then in 1830, Barthélemy Thimonnier, a French tailor, opened the first machine-based clothing manufacturing company to make uniforms for the French army. But there was one drawback - the other local tailors were so afraid that Thimonnier would undercut their trade that they torched his factory - WITH HIM INSIDE! Fortunately, he survived. Perhaps that is why an American, Walter Hunt, didn't patent his design in 1834. He said he was afraid it would lead to massive unemployment. Enter Elias Howe in 1845. After an unsuccessful marketing trip to England, he returned to the States to find that Isaac Merritt Singer had copped his design. Howe sued Singer for Patent Infringement and won. After the dust settled, both men ended up millionaires, and home and commercial sewing were revolutionized. Soon, many other companies entered the market. Sewing machines were one of the first mass- market complex consumer goods distributed around the globe. By 1920 they were nearly everywhere - in cities, towns, and tiny hamlets. There's even a memorable scene in Fiddler on the Roof in which Motel has his new machine blessed by the village of Anatevka's rebbe. -

Medieval Textiles Coordinator: Nancy M Mckenna 507 Singer Ave

Issue 32 June 2002 Complex Weavers’ ISSN: 1530-763X Medieval Textiles Coordinator: Nancy M McKenna 507 Singer Ave. Lemont, Illinois 60439 e-mail:[email protected] In this issue: Block Printing Block Printing p.1 by: Mr. Mohamedhusain Khatri News from the Coordinator p.1 Adventures in Research p.3 Indigo (Neel) dyeing and the use of block-printing to The Pallium p.5 produce patterns on cloth have been known for Upcoming Events p.8 centuries. The transforming properties of the Indigo Sample list p.8 plant (ASURI) find a mention in the Atharva Veda and the varied tones of Indigo Blue appear in clothes News from the Coordinator worn by men and women in the Rock Paintings of by Nancy M McKenna Ajanta, Bagh and in the Wall Paintings of Alchi and Tanjore. Indian cloth, with their fast dyes and varied Convergence year… there is a special ring to that designs was famous throughout the ancient world. phrase. It is the year when weavers from all over The earliest specimen of Indian dyed and block- converge upon one city for stimulating and enriching printed cloth, apart from the fragment found at activities that expand their fiber horizons. Even if one Harappa, dates back to the 8th Century. Innumerable does not attend Convergence (& Complex Weavers fragments of block-printed, dyed cloth have been Seminars) that spark is felt in all the fiber events discovered in the tombs at Fostat in Egypt. An everywhere that year. It is the regenerative year. It is analysis of the Indigo Dye in these Fostat fabrics has the year for field trips near and far. -

Kwaggasrand School Year 2 English: First Additional Language Week 4 Term 2 Dear Year 2 Learner, This Document Contains the Work for Week 4 Term 2

Kwaggasrand School Year 2 English: First Additional Language Week 4 Term 2 Dear Year 2 learner, This document contains the work for Week 4 Term 2. The work consists of 4 sections namely: 1. Listening and Speaking 2. Reading and Viewing 3. Writing and Presenting 4. Language Structure and Conventions Remember the following: Complete all the activities/answers in a separate book or on a sheet of paper. Write the heading, week and date for every activity you do e.g. Listening and Speaking Week 4 4 May 2020 Your parents/guardians are allowed to help and guide you should you struggle, but you need to complete the work yourself. Please bring along all completed work when the school reopens again. Good luck and just try your best! Stay safe! Regards Ms. Z. Esterhuyse 1 Kwaggasrand School Year 2 English: First Additional Language Week 4 Term 2 Listening and Speaking Discuss the invention of sewing machines with a parent/guardian. Understand and use new vocabulary (page 4) Answer questions orally (page 4) Sewing machine, any of various machines for stitching material (such as cloth or leather), usually having a needle and shuttle to carry thread and powered by treadle, waterpower, or electricity. It was the first widely distributed mechanical home appliance and has been an important industrial machine. Detail of contemporary sewing machine parts: needle, needle bar, presser foot, feed dog, bobbin case, shuttle (loop taker), machine bed, and plate. An early sewing machine was designed and manufactured by BarthélemyThimonnier of France, who received a patent for it by the French government in 1830, to mass-produce uniforms for the French army, but some 200 rioting tailors, who feared that the invention would ruin their businesses, destroyed the machines in 1831. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

MINUTES of the 84Th MEETING of AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD

THE 115th MEETING OF AYNHO HISTORY SOCIETY HELD AT THE VILLAGE HALL, AYNHO ON WEDNESDAY 29th APRIL 2019 Present:- Keith McClellan – Chairman Peter Cole – Secretary 1) Secretary’s Report Peter said that he went to the AGM of the Northamptonshire Heritage Forum at Boughton House, Geddington, which was between Kettering and Corby the day after our last meeting. In fact he made it a day trip by going first to the Northants Records Office, which was on the way. One of his reasons for doing this was because at least two people had told him that they thought that Arthur Seccull had been the illegitimate son of Joyce Hobcraft. One of his reasons for going to the Records Office was to go through all the records of towns and villages fairly close to Aynho to see if there was any record of his birth there. He couldn’t find anything, but of course she could have gone to a nearby Oxfordshire village. Going on to the Heritage Forum AGM, he eventually found Boughton House. There were a lot of people from all over the county. He added a further 20 Aynho leaflets to the ones the Secretary had left over from the Brackley meeting, amongst a lot of leaflets from all over the county. He took a lot of other people’s leaflets from the meeting. 2) Keith introduced Jon-Paul Carr to talk on “Inventions and Inventors of Victorian Northamptonshire.” Jon-Paul said that he had been asked by Northampton Museum to give a talk about Victorian Northampton. At that time there had been a programme on television by Adam Hart-Davis on “What did the Victorians do for us?” It made me think – there must have been some inventions at that time in Northants.