A Critique of the Global Trafficking Discourse and U.S. Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migrant Smuggling in Asia

Migrant Smuggling in Asia An Annotated Bibliography August 2012 2 Knowledge Product: !"#$%&'()!*##+"&#("&(%)"% An Annotated Bibliography Printed: Bangkok, August 2012 Authorship: United Nations O!ce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Copyright © 2012, UNODC e-ISBN: 978-974-680-330-4 "is publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-pro#t purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNODC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations O!ce on Drugs and Crime. Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the reproduction, should be addressed to UNODC, Regional Centre for East Asia and the Paci#c. Cover photo: Courtesy of OCRIEST Product Feedback: Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to: Coordination and Analysis Unit (CAU) Regional Centre for East Asia and the Paci#c United Nations Building, 3 rd Floor Rajdamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200, "ailand Fax: +66 2 281 2129 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org/eastasiaandpaci#c/ UNODC gratefully acknowledges the #nancial contribution of the Government of Australia that enabled the research for and the production of this publication. Disclaimers: "is report has not been formally edited. "e contents of this publication do not necessarily re$ect the views or policies of UNODC and neither do they imply any endorsement. -

Emancipating Modern Slaves: the Challenges of Combating the Sex

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 Emancipating Modern Slaves: The hC allenges of Combating the Sex Trade Rachel Mann Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Mann, Rachel, "Emancipating Modern Slaves: The hC allenges of Combating the Sex Trade" (2013). Honors Theses. 700. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/700 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMANCIPATING MODERN SLAVES: THE CHALLENGES OF COMBATING THE SEX TRADE By Rachel J. Mann * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Political Science UNION COLLEGE June, 2013 ABSTRACT MANN, RACHEL Emancipating Modern Slaves: The Challenges of Combating the Sex Trade, June 2013 ADVISOR: Thomas Lobe The trafficking and enslavement of women and children for sexual exploitation affects millions of victims in every region of the world. Sex trafficking operates as a business, where women are treated as commodities within a global market for sex. Traffickers profit from a supply of vulnerable women, international demand for sex slavery, and a viable means of transporting victims. Globalization and the expansion of free market capitalism have increased these factors, leading to a dramatic increase in sex trafficking. Globalization has also brought new dimensions to the fight against sex trafficking. -

General Assembly Distr

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/11/6/Add.1 26 May 2009 ENGLISH/FRENCH/SPANISH ONLY HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Eleventh session Agenda item 3 PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF ALL HUMAN RIGHTS, CIVIL, POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL, INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO DEVELOPMENT Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Yakin Ertürk* Addendum COMMUNICATIONS TO AND FROM GOVERNMENTS** * The report was submitted late in order to reflect the most recent information. ** The report is being circulated in the languages of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.09-13435 (E) 090609 A/HRC/11/6/Add.1 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 1 - 3 4 II. OVERVIEW OF COMMUNICATIONS .......................................... 4 - 10 4 III. COMMUNICATIONS SENT AND GOVERNMENT REPLIES RECEIVED ....................................................................... 11 - 671 6 Afghanistan ........................................................................................ 12 - 24 7 Bahrain ............................................................................................... 25 - 43 8 Brazil .................................................................................................. 44 - 46 11 Canada ............................................................................................... 47 - 64 11 Colombia -

Sexual Slavery Without Borders: Trafficking for Commercial Sexual

International Journal for Equity in Health BioMed Central Research Open Access Sexual slavery without borders: trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation in India Christine Joffres*1, Edward Mills1, Michel Joffres1, Tinku Khanna2, Harleen Walia3 and Darrin Grund1 Address: 1Simon Fraser University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Blusson Hall, Room 11300, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6, Canada, 2State Coordinator, Bihar Anti-trafficking Resource, Centre Apne Aap Women Worldwide http://www.apneaap.org, Jagdish Mills Compound, Forbesganj, Araria, Bihar 841235, India and 3Technical Support – Child Protection, GOI (MWCD)/UNICEF, 253/A Wing – Shastri Bhavan,, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Marg,, New Delhi:110001, India Email: Christine Joffres* - [email protected]; Edward Mills - [email protected]; Michel Joffres - [email protected]; Tinku Khanna - [email protected]; Harleen Walia - [email protected]; Darrin Grund - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 25 September 2008 Received: 17 March 2008 Accepted: 25 September 2008 International Journal for Equity in Health 2008, 7:22 doi:10.1186/1475-9276-7-22 This article is available from: http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/7/1/22 © 2008 Joffres et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Trafficking in women and children is a gross violation of human rights. However, this does not prevent an estimated 800 000 women and children to be trafficked each year across international borders. Eighty per cent of trafficked persons end in forced sex work. -

The Kingdom of Bahrain on Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Financing of Terrorism

Middle East & North Africa Financial Action Task Force Mutual Evaluation Report Of The Kingdom of Bahrain On Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Financing of Terrorism This Detailed Assessment Report on anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism for Bahrain was prepared by the International Monetary Fund. The report assesses compliance with the FATF 40+9 Recommendations and uses the FATF methodology of 2004. The report was adopted as a MENAFATF Mutual Evaluation by the MENAFATF Plenary on November 14th, 2006. All rights reserved © 2006 – MENAFATF, P.O. Box 10881, Manama KINGDOM OF BAHRAIN TABLE OF CONTENTS A. PREFACE ____________________________________________________________________5 B. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ________________________________________________________5 C. GENERAL ___________________________________________________________________10 D. TABLE 1: DETAILED ASSESSMENT ____________________________________________20 - Legal system and related institutional measures _________________________________ 20 - Preventive measures - Financial institutions ____________________________________ 31 - Preventive measures - Designated non-financial businesses and professions ____ _______54 - Legal persons, legal arrangements, and non-profit organizations ____________________ 67 - National and international cooperation ________________________________________71 TABLE 2: Ratings of Compliance with FATF Recommendations __________________________77 TABLE 3: Recommended Action Plan for Improving the AML/CFT System _______________81 -

2017 Trafficking in Persons Report

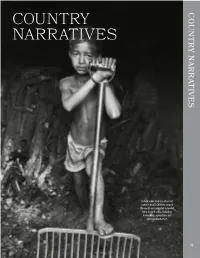

COUNTRY NARRATIVES COUNTRY COUNTRY NARRATIVES A child rakes coal in a charcoal camp in Brazil. Children around the world are subjected to forced labor in rural areas, including in ranching, agriculture, and charcoal production. 55 protection, and law enforcement strategies; improve efforts to collect, analyze, and accurately report counter-trafficking data; AFGHANISTAN: TIER 2 dedicate resources to support long-term victim rehabilitation programs; continue to educate government officials and the The Government of Afghanistan does not fully meet the public on the criminal nature of bacha baazi and debt bondage minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking; however, of children; and proactively inform government officials, it is making significant efforts to do so. The government especially at the MOI and Ministry of Defense (MOD), of the demonstrated increasing efforts compared to the previous law prohibiting the recruitment and enlistment of minors, and reporting period; therefore, Afghanistan was upgraded to Tier 2. enforce these provisions with criminal prosecutions. The government demonstrated increasing efforts by enacting a new law on human trafficking in January 2017 that attempts to reduce conflation of smuggling and trafficking, and criminalizes PROSECUTION bacha baazi, a practice in which men exploit boys for social and The government increased its law enforcement efforts. In January sexual entertainment. The government investigated, prosecuted, 2017, the government enacted the Law to Combat Crimes and convicted traffickers, including through the arrest and of Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants, which punishment of complicit officials for bacha baazi. With funding prohibits all forms of human trafficking. The law criminalizes and staff from an international organization, the government the use of threat or force or other types of coercion or deceit for AFGHANISTAN reopened a short-term shelter in Kabul for trafficking victims. -

A-Governmental Coordination and Years’ Imprisonment Or a Fine Under This Law Are Not Cooperation in Vulnerable Southern Border Prov- Sufficiently Stringent

COUNTRY NARRATIVES 52 AFGHANISTAN AFGHANISTAN (Tier 2) Prosecution The Government of Afghanistan did not provide Afghanistan is a source, transit, and destination sufficient evidence of efforts to punish traffick- country for men, women, and children trafficked for ing over the reporting period. Afghanistan does the purposes of commercial sexual exploitation and not prohibit all forms of trafficking, but relies forced labor. Afghan children are trafficked within the on kidnapping and other statutes to charge country for commercial sexual exploitation, forced some trafficking offenses. These statutes do not marriage to settle debts or disputes, forced begging, specify prescribed penalties, so it is unclear whether debt bondage, service as child soldiers, and other penalties are sufficiently stringent and commen- forms of forced labor. Afghan women and girls are surate with those for other grave crimes, such as also trafficked internally and to Pakistan, Iran, Saudi rape. Despite the availability of some statutes, Arabia, Oman, and elsewhere in the Gulf for commer- Afghanistan did not provide adequate evidence of cial sexual exploitation. Afghan men are trafficked to arresting, prosecuting, or convicting traffickers. The Iran for forced labor. Afghanistan is also a destination government reported data indicating traffickers had for women and girls from China, Iran, and Tajikistan been prosecuted and convicted, but was unable to trafficked for commercial sexual exploitation. Tajik provide disaggregated data. There was no evidence women and children are also believed to be traf- that the government made any efforts to investigate, ficked through Afghanistan to Pakistan and Iran for arrest, or prosecute government officials facilitating commercial sexual exploitation. trafficking offenses despite reports of widespread complicity among border and highway police. -

Countering Violent Extremism the Counter Narrative Study

! COUNTERING VIOLENT EXTREMISM THE COUNTER NARRATIVE STUDY “Countering the Narratives of Violent Extremism FOREWORD The Achilles’ heel of our strategy against terrorism and violent extremism has been the failure to counter the narratives that groups use to recruit. As long as groups attract a steady stream of new members, the terrorism and violence will continue. This is why the strategy known as Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) is so important, and must be used as a counterterrorism tool alongside military, intelligence, and law enforcement operations. Through our partnership with the Qatar International Academy for Security Studies (QIASS), we offer critical guidance to those wishing to counter the narratives of violence and extremism. “Countering Violent Extremism: The Counter-Narrative Study” is the result of a year- long research project conducted by our team of former top law enforcement, intelligence, and counterterrorism officials. We traveled around the world, from Malaysia to Kenya to Norway to Northern Ireland to the United States, studying extremist and terrorist groups and interviewing their members, as well as those in government and other important stakeholders responsible for tackling the problem. As you will see from our “Findings,” we’ve put together some essential lessons. One of the most important takeaways is understanding the pattern(s) behind group recruitment. Terrorist and extremist groups first prey on local grievances—exploiting feelings of anger, humiliation, resentment, or lack of purpose. They then incorporate, into their violent pronouncements, conspiratorial messages that blame those they are targeting. Self-proclaimed religious groups use distorted religious edicts in their narratives. Recruiters achieve success by providing both answers and a sense of purpose to vulnerable individuals. -

Lucknow 226010

3 . <65 * = = = 45(<49,32/ 45 4 6 7489 548: " 5 @ 7+6A+ 9.,@,+?9B,69 +C7:,88: ,./.7$+9- 8/95.8/78+,?-: B,:?6A ??9.B,5:.,+6 9769@0?6+D 6,?6 :+$/:57: $/+):/ ,/:7+ /A,:8BCA- . $ %&;024 44+ "32 > ? , ! -! = ""-"#"#> ,/. % 12 $ R !!"#$ "$% & +,-,./ “As a measure of abundant % 1 precaution, passengers arriving 0#11"2& 3##'00(#112# +,-,./ mid fears over the spread from the UK in all transit * 10'&300&'04##3&'2 % 0! Aof a mutated strain of coro- flights (flights that have taken armers sitting on Delhi’s navirus — reportedly 70 per off or flights which are reach- 5 #(#1"( ('(##4(#4( Fborders with Haryana and R cent more infectious than the ing India before December 22 6+ #'(14& 00112(#43(& Uttar Pradesh began their day- one that caused the Covid-19 at 23.59 hrs) should be subject ,-##-$0-#$1 ('2#(' �( 430 long “relay” hunger strike at all 11 members sat on hunger — India has joined over two to mandatory RT-PCR test on protest sites on chilling strike in the first batch. '45&'46('7'4P dozen countries in suspending arrival at the airports con- ,-/2-,./ 40(#'# ,#-.#/21#&31 Monday. Another batch of 11 members all flights from and to the cerned,” the Ministry said. 7 5 2(34"0 #01423101' Meanwhile, the farmer will sit on a hunger strike at 11 45'*((65'4&8( United Kingdom from Civil Aviation Minister % - 8 2"#"3" 13'020&'"1 leaders on Monday claimed am on Tuesday. December 23 to December 31. Hardeep Singh Puri said on that there is nothing new in the Meanwhile, several farmers 79(&+5'( Union Health Minister Twitter that those passengers 12-.0-#$, 9 "&4214 0#1& "&043( Centre’s latest letter to them also contributed to the hunger Dr Harshvardhan said the who are found Covid positive %"-1,-,33 :; &111'1 &4&4"&& seeking a date for the next strike and stayed without food New Delhi: A day after authorities are keeping a close would be sent for institution- 6 �("' 0202&("4&2 round of talks and said they are for the entire day. -

2017 Trafficking in Persons Report

are often subjected to sex trafficking in Italy after accepting trafficking victims who were provided government shelter and JAMAICA promises of employment as dancers, singers, models, restaurant services, and increased awareness-raising efforts. However, the servers, or caregivers. Romanian and Albanian criminal groups government did not meet the minimum standards in several force Eastern European women and girls into commercial sex. key areas. The government did not hold complicit officials Nigerians represent 21 percent of victims, with numbers nearly accountable, publish a standard victim protection protocol, doubling in 2016 to approximately 7,500 victims. Nigerian or publish an annual report monitoring its efforts. women and girls are subjected to sex and labor trafficking through debt bondage and coercion through voodoo rituals. Men from Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe are subjected to forced labor through debt bondage in agriculture in southern Italy and in construction, house cleaning, hotels, and restaurants in the north. Chinese men and women are forced to work in textile factories in Milan, Prato, Rome, and Naples. Children subjected to sex trafficking, forced begging, and forced criminal activities are from Romania, Nigeria, Brazil, Morocco, and Italy, particularly Romani and Sinti boys who may have been born in Italy. Transgender individuals from Brazil and Argentina are subjected to sex trafficking in Italy. Unaccompanied children RECOMMENDATIONS FOR JAMAICA are at risk of trafficking, particularly boys from Somalia, Eritrea, Vigorously prosecute, convict, and punish traffickers, including Bangladesh, Egypt, and Afghanistan, who often work in shops, any officials complicit in sex or labor trafficking; increase bars, restaurants, and bakeries to repay smuggling debts. -

How to Read a Country Narrative

/V^[V9LHKH*V\U[Y`5HYYH[P]L This page shows a sample country narrative. The Prosecution, Protection, and Prevention sections of each country narrative describe how a government has or has not addressed the relevant TVPA minimum standards (see page 388), during the reporting period. This truncated narrative gives a few examples. The country’s tier ranking is based on the government’s eIIorts against traIÀcking as measured by the TVPA TVPA Minimum minimum standards. Standard 4(2) – whether the government adequately protects victims of trafmcLing by identifying 7YV[LJ[PVU COUNTRY X (Tier 2 Watch List) them and ensuring they have Country X made minimal progress in protecting victims of access to necessary Country X is a transit and destination country for men trafficking during the reporting period. Although health and women subjected to forced labor and, to a much lesser care facilities reportedly refer suspected abuse cases to the services. extent, forced prostitution. Men and women from South and government anti-trafficking shelter for investigation, tthehe Southeast Asia, East Africa, and the Middle East voluntarily governmentgovernment continues to lacklack a systematicsystematic procedureprocedure forfor lawlaw travel to Country X as laborers and domestic servants, but enforcement to identify victims of trafficking among vulnerablee some subsequently face conditions indicative of involuntary populations,populations, such as foreign workers awaiting deportation and servitude. These conditions include threats of serious harm, women arrested for prostitution; as a result, victims may be including threats of legal action and deportation; withholding punished and automatically deported without being identified ProÀOe oI Summary of the of pay; restrictions on freedom of movement, including the as victims or offered protection. -

2016 Trafficking in Persons Report

COUNTRY NARRATIVES COUNTRY NARRATIVES In Peruvian mining towns, women and girls are exploited in sex trafficking in brothels, often after having been fraudulently recruited and trapped in debt bondage. Some of the miners who frequent the brothels and exploit the sex trafficking victims might be victims of forced labor themselves. 65 Nepal, India, Iran, Pakistan, and Tajikistan; the recruiters subject AFGHANISTAN: these migrants to forced labor after arrival. Tier 2 Watch List In 2015, widespread and credible reporting from multiple Afghanistan is a source, transit, and destination country for sources indicated both the government and armed non-state men, women, and children subjected to forced labor and groups in Afghanistan continued to recruit and use children in sex trafficking. Internal trafficking is more prevalent than combat and non-combat roles. The UN verified and reported transnational trafficking. Most Afghan trafficking victims are an increase in the number of children recruited and used in children who end up in carpet making and brick factories, Afghanistan, mostly by the Taliban and other armed non-state domestic servitude, commercial sexual exploitation, begging, actors. In January 2011, the Afghan government signed an action poppy cultivation, transnational drug smuggling, and assistant plan with the UN to end and prevent the recruitment and truck driving within Afghanistan, as well as in the Middle East, use of children by the Afghan National Defense and Security Europe, and South Asia. NGOs documented the practice of Forces (ANDSF), and in 2014, they endorsed a road map to bonded labor, whereby customs allow families to force men, accelerate the implementation of the action plan.