Open PDF in a New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Iconographies of Urban Masculinity: Reading “Flex Boards” in an Indian City

Iconographies of Urban Masculinity: Reading “Flex Boards” in an Indian City By Madhura Lohokare, Shiv Nadar University Asia Pacific Perspectives v15n1. Online Article Introduction On an unusually warm evening in early May of 2012 I rode my scooter along the congested lanes of Moti Peth1 on my way to “Shelar galli,2” a working-class neighborhood in the western Indian city of Pune, where I had been conducting my doctoral field research for the preceding fifteen months. As I parked my scooter at one end of the small stretch of road that formed the axis of the neighborhood, it was impossible to miss a thirty-foot-tall billboard looming above the narrow lane at its other end. I was, by now, familiar with the presence of “flex” boards, as they were popularly known, as these boards crowded the city’s visual and material landscape. However, the flex board in Shelar galli that evening was striking, given its sheer size and the way in which it seemed to dwarf the neighborhood with its height (see figure 1.1). Figure 1.1 Flex board marking the occasion of Mohanlal’s birthday, erected in Shelar Galli, Pune (Photo by author) The image of Mohanlal Shitole, a resident of Shelar galli, dressed in a bright red turban and a starched white shirt, with a thick gold bracelet resting on his wrist, stood along the entire length of the flex making it seem like he was towering above the narrow lane itself. The rest of the space was dotted with faces of a host of local politicians (all men, barring one woman councilor) and (male) residents of the neighborhood, on whose behalf collective birthday greetings for Mohanlal were printed on top of the flex. -

Movie Promotional Strategies in Tamil Film Industry-The Contemporary Access

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8, Issue-11S, September 2019 Movie Promotional Strategies in Tamil Film Industry-the Contemporary Access Mahesh.V.J, Gigi.G.S, P.Uma Rani ABSTRAC-; Movie Industry of India had many ups and screened in London in 1914 and this movie was made in downs since 19th century. Some movies succeed with high box Marthi language. The number of production companies office collection records, while some were not. Some movies takes increased in early 1920s and mythological and historical attention with high promotions while some movies not even films from epic Mahabharata and Ramayana were noticed by the viewers. Movie viewers have variety of choices on types of movie like realistic, imaginary, fiction and commercial dominated and welcomed by Indian audience. Hollywood movies. Taking all of them to movie theatre need well planned had an entry during early 1920s and could highly satisfy strategies. As we know like every other service, movies also need audience of Indian movies by offering them action oriented Marketing. Movie making houses need to understand the films. marketing strategies need to be framed and reframed in respect to the nature of movies. II. SOUTH INDIAN MOVIE INDUSTRY The present research, ‘Movie promotional strategies in Tamil film industry-the contemporary approach’, deals with Cinema of South India is combined of five different film promotional aspects of the Tamil Film Industry in recent times. industries of South India; Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil, The present study reveals that promotional strategies being Telugu and Tulu and they are based on Bengaluru, Kochi, followed in Tamil movies creating great impact on movie Chennai, Hyderabad and Mangalore respectively. -

In the Contemporary Malayalam Cinema

JAC : A Journal Of Composition Theory ISSN : 0731-6755 THE KALEIDOSCOPIC ‘TRANSGRESSSIONS’ OF ‘NOUVEAU FEMME’ IN THE CONTEMPORARY MALAYALAM CINEMA Christina Mary Georgy MA English Language and Literature(2017-2019), Institute of English, University of Kerala, Trivandrum, Kerala, India. Abstract: In the present-daysituation, motion pictures, being one of the most resourcefulmass mediaexpressions,perform not only as a powerfulpodium for amusement but also as aproficient site of substantial ideological negotiation and contestation. The politics of representation of women on the silver screen has always been a problematic discourse, owing to the phallogocentric, hegemonic constructs of the society worldwide.This research paper makes use of insights provided by popular gender, media and cultural studies theorists to map out the distinctive features of the ‘nouveau femme’ by tracing out the history and politics of representation of women in Malayalam cinemaover the decades. This paper also attempts to read against the grain of female transgressions in Mollywood with special reference to select critically acclaimed Malayalam films of post 2015 era. Keywords: Cinema, Gender, Media, Modernity, Representation, Woman Representation of Women in Malayali Public and Private Sphere The position of women in Malayali public and private sphere has always been a stimulating discourse in the academic milieu. Kerala has had an age old history of a Volume XIV, Issue VII, JULY 2021 Page No: 10 JAC : A Journal Of Composition Theory ISSN : 0731-6755 matrilineal system of inheritance which used to function as a "surrogate patriarchy” of sorts with actual power being vested on the ammavan or the maternal uncle, functioning as the kaaranavar of the tharavad . -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

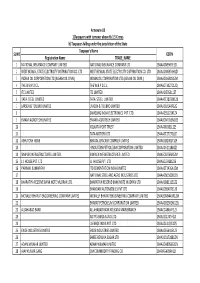

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

!Ncredible Kerala? a Political Ecological Analysis of Organic Agriculture in the “Model for Development”

!ncredible Kerala? A Political Ecological Analysis of Organic Agriculture in the “Model for Development” By: Sapna Elizabeth Thottathil A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jake Kosek, Chair Professor Michael Watts Professor Nancy Peluso Fall 2012 ABSTRACT !ncredible Kerala? A Political Ecological Analysis of Organic Agriculture in the “Model for Development” By Sapna Elizabeth Thottathil Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Jake Kosek, Chair In 2010, the South Indian state of Kerala’s Communist-led coalition government, the Left Democratic Front (LDF), unveiled a policy to convert the entirety of the state to organic farming within ten years; some estimates claim that approximately 9,000 farmers were already participating in certified organic agriculture for export at the time of the announcement. Kerala is oftentimes hailed as a “model for development” by development practitioners and environmentalists because of such progressive environmental politics (e.g., McKibben 1998). Recent scholarship from Political Ecology, however, has christened organic farming as a neoliberal project, and much like globalized, conventional agriculture (e.g., Guthman 2007 and Raynolds 2004). Drawing from fourteen months of fieldwork in Kerala between 2009-2011, I explore this tension between Kerala as a progressive, political “model,” and globalized, corporatized organic agriculture. I utilize Kerala’s experiences with organic farming to present another story about North-South relations in globalized organic farming. In contrast to recent Political Ecological work surrounding alternative food systems, I contend that organic agriculture can actually offer meaningful possibilities for transforming the global agricultural system in local places. -

Mohanlal Filmography

Mohanlal filmography Mohanlal Viswanathan Nair (born May 21, 1960) is a four-time National Award-winning Indian actor, producer, singer and story writer who mainly works in Malayalam films, a part of Indian cinema. The following is a list of films in which he has played a role. 1970s [edit]1978 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes [1] 1 Thiranottam Sasi Kumar Ashok Kumar Kuttappan Released in one center. 2 Rantu Janmam Nagavally R. S. Kurup [edit]1980s [edit]1980 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Manjil Virinja Pookkal Poornima Jayaram Fazil Narendran Mohanlal portrays the antagonist [edit]1981 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Sanchari Prem Nazir, Jayan Boban Kunchacko Dr. Sekhar Antagonist 2 Thakilu Kottampuram Prem Nazir, Sukumaran Balu Kiriyath (Mohanlal) 3 Dhanya Jayan, Kunchacko Boban Fazil Mohanlal 4 Attimari Sukumaran Sasi Kumar Shan 5 Thenum Vayambum Prem Nazir Ashok Kumar Varma 6 Ahimsa Ratheesh, Mammootty I V Sasi Mohan [edit]1982 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Madrasile Mon Ravikumar Radhakrishnan Mohan Lal 2 Football Radhakrishnan (Guest Role) 3 Jambulingam Prem Nazir Sasikumar (as Mohanlal) 4 Kelkkatha Shabdam Balachandra Menon Balachandra Menon Babu 5 Padayottam Mammootty, Prem Nazir Jijo Kannan 6 Enikkum Oru Divasam Adoor Bhasi Sreekumaran Thambi (as Mohanlal) 7 Pooviriyum Pulari Mammootty, Shankar G.Premkumar (as Mohanlal) 8 Aakrosham Prem Nazir A. B. Raj Mohanachandran 9 Sree Ayyappanum Vavarum Prem Nazir Suresh Mohanlal 10 Enthino Pookkunna Pookkal Mammootty, Ratheesh Gopinath Babu Surendran 11 Sindoora Sandhyakku Mounam Ratheesh, Laxmi I V Sasi Kishor 12 Ente Mohangal Poovaninju Shankar, Menaka Bhadran Vinu 13 Njanonnu Parayatte K. -

Baahubali to Mahanati, 5 Movies That Made Telugu Film Industry Proud Meet the Leading Characters of Khaali Peeli

Ad Now Reading: Baahubali to Mahanati, 5 Movies That Made Telugu Film Industry Pr... Share ! " # $ Comments (0) Reduce Asthma Symptoms Don't Put Up With AsthmaticGet Airways- Help Buying Schedule Glasses a Visit to Your GP for an Asthma Action Plan Oscar Wylee - Optometrist Our new collection & bulk billed eye tests Casey Superclinic Open Narre Warren WEBSITE DIRECTIONS Mumbai (Maharashtra) Powered by Bombay Times, Log in & Claim your 6 points Sign In facebooktwitter +5 more THE TIMES OF INDIA Go to Etimes Search TOI Movies News Movie Reviews Movie Listings Showtimes Awards SPONSORED STORIES Hindi English Tamil Telugu Malayalam Kannada Bengali Punjabi Marathi Bhojpuri Gujarati Add the tadka of health to your cravings TRENDING NOW: Karisma Kapoor Rhea’s Bail Tamannaah Bhatia Sandip Ssingh Sushant Case Sushant Forensic Report Ranbir-Alia Prasoon Joshi News » Entertainment » Telugu » Movies » Baahubali to Mahanati, 5 Movies That Made Telugu Film Industry Proud Meet the leading characters of Khaali Peeli Khaali Peeli trio is Baahubali to Mahanati, 5 Movies That Made Telugu Film Industryhere to win your Proud hearts TIMESOFINDIA.COM | Last updated on - Oct 1, 2020, 21:11 IST Share ! " # $ Comments (0) FEATURED IN LIFESTYLE 01 /6 There are so many Telugu films that have won hearts and wowed Subtle ways of the audiences not only in India but also at international film festivals expressing your love, as per sunsign Eggs vs Paneer: Which is a better source of protein… and beneficial for weight lo... An expert guide on what foods to eat and avoid for… glowing skin and healthy hair Types of fat-soluble vitamins Why work friendships will be more important in… new norm SEE ALL FEATURED IN MOVIES Kangana shares BTS Not all Telugu movies are bad, but some of them are shitty masala movies. -

Class 35 to Notice

Trade Marks Journal No: 1433 , 01/02/2010 Class 35 ALLSPRAY Advertised before Acceptance under section 20(1) Proviso 1242070 08/10/2003 ALLSPRAY LLC trading as ALLSPRAY LLC PO BOX 87707, CAROL STREAM, IL 60188-7707, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA SERVICE PROVIDERS DELAWARE LIMITED LIABILITY CORPORATION Address for service in India/Agents address: DEPENNING & DEPENING INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY HOUSE, 31 SOUTH BANK ROA, CHENNAI 600028,INDIA. Used Since :09/10/2000 CHENNAI PROVIDING ONLINE RETAIL SERVICES OVER A GLOBAL COMPUTER NETWORK FEATURING SPRAY NOZZLES AND SPRAY ASSEMBLIES AND PARTS AND ACCESSORIES THEREFORE FOR INDUSTRIAL AND AGRICULTURAL USES V. NATARAJAN, ASSISTANT REGISTRAR OF TRADE MARKS, CHENNAI 1579 Trade Marks Journal No: 1433 , 01/02/2010 Class 35 U2 Advertised before Acceptance under section 20(1) Proviso 1392826 19/10/2005 G2000 ( APPAREL) LIMITED PENTHOUSE, WYLER CENTRE II, 200, TAI LIN PAI ROAD, KWAI CHUNG, NEW TERRITORIES, HONG KONG. Manufacturers, Traders and Service Providers A limited liability company organized and existing under the laws of Hong Kong. Address for service in India/Agents address: ANAND AND ANAND. B-41,NIZAMUDDIN EAST, NEW DELHI - 110 013. Proposed to be Used DELHI Wholesale, retail, distributorship and trading services relating to clothing, footwear, headgear, umbrellas, belts of all materials, bags of all types and of all materials, goods made of leather and imitations of leather, jewellery and ornaments, fashion accessories. A.G.AMARE, EXAMINER OF TRADE MARKS, DELHI 1580 Trade Marks Journal No: 1433 , 01/02/2010 Class 35 CONFIRM Advertised before Acceptance under section 20(1) Proviso 1422191 17/02/2006 RAHUL MALHOTRA. 502, MALHOTRA CHAMBERS, 31/33, POLICE COURT LANE, FORT, MUMBAI-400 001. -

Details of Unclaimed Deposits / Inoperative Accounts

CITIBANK We refer to Reserve Bank of India’s circular RBI/2014-15/442 DBR.No.DEA Fund Cell.BC.67/30.01.002/2014-15. As per these guidelines, banks are required to display the list of unclaimed deposits/inoperative accounts which are inactive/ inoperative for ten years or more on their respective websites. This is with a view of enabling the public to search the list of account holders by the name of: Account Holder/Signatory Name Address HASMUKH HARILAL 207 WISDEN ROAD STEVENAGE HERTFORDSHIRE ENGLAND UNITED CHUDASAMA KINGDOM SG15NP RENUKA HASMUKH 207 WISDEN ROAD STEVENAGE HERTFORDSHIRE ENGLAND UNITED CHUDASAMA KINGDOM SG15NP GAUTAM CHAKRAVARTTY 45 PARK LANE WESTPORT CT.06880 USA UNITED STATES 000000 VAIDEHI MAJMUNDAR 1109 CITY LIGHTS DR ALISO VIEJO CA 92656 USA UNITED STATES 92656 PRODUCT CONTROL UNIT CITIBANK P O BOX 548 MANAMA BAHRAIN KRISHNA GUDDETI BAHRAIN CHINNA KONDAPPANAIDU DOOR NO: 3/1240/1, NAGENDRA NAGAR,SETTYGUNTA ROAD, NELLORE, AMBATI ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA INDIA 524002 DOOR NO: 3/1240/1, NAGENDRA NAGAR,SETTYGUNTA ROAD, NELLORE, NARESH AMBATI ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA INDIA 524002 FLAT 1-D,KENWITH GARDENS, NO 5/12,MC'NICHOLS ROAD, SHARANYA PATTABI CHETPET,CHENNAI TAMILNADU INDIA INDIA 600031 FLAT 1-D,KENWITH GARDENS, NO 5/12,MC'NICHOLS ROAD, C D PATTABI . CHETPET,CHENNAI TAMILNADU INDIA INDIA 600031 ALKA JAIN 4303 ST.JACQUES MONTREAL QUEBEC CANADA CANADA H4C 1J7 ARUN K JAIN 4303 ST.JACQUES MONTREAL QUEBEC CANADA CANADA H4C 1J7 IBRAHIM KHAN PATHAN AL KAZMI GROUP P O BOX 403 SAFAT KUWAIT KUWAIT 13005 SAJEDAKHATUN IBRAHIM PATHAN AL KAZMI -

An Exploration of Gendered Colourism and Representation of Dark-Skinned Women in Malayalam Movies

1 TINCTION OF BROWN BODIES: AN EXPLORATION OF GENDERED COLOURISM AND REPRESENTATION OF DARK-SKINNED WOMEN IN MALAYALAM MOVIES By Uthara Geetha Main Supervisor: Prof. Isabel Suárez Carrera (Universidad de Oviedo) Second Supervisor: Dr Clare Bielby (University of York) Submitted to Universidad de Oviedo, Centro de Investigaciones Feministas (CIFEM) Oviedo, Spain 2021 2 TINCTION OF BROWN BODIES: AN EXPLORATION OF GENDERED COLOURISM AND REPRESENTATION OF DARK-SKINNED WOMEN IN MALAYALAM MOVIES By Uthara Geetha Main Supervisor: Prof. Isabel Suárez Carrera (Universidad de Oviedo) Second Supervisor: Dr Clare Bielby (University of York) Submitted to Universidad de Oviedo, Centro de Investigaciones Feministas (CIFEM) Oviedo, Spain 2021 Approval signed by Main Supervisor: 3 Abstract Indian society suffers from deep-rooted colourism emerging from its complex history of early racial mixing, rigid social systems and colonialization, which results in the active practice of skin- colour based discrimination in socio-cultural spaces. Due to the mixed-race and culturally diverse nature of Indian society, this study sought to decode colourism as a racial hierarchy which is intertwined with other forms of discriminations. In particular, I argue, pre-existing indigenous social inequalities— caste, class and region— were reinterpreted in terms of skin colour following co-option of colonial racist ideologies by native elite to legitimise discrimination against the historically oppressed groups. Colourism is perpetuated through popular stereotypes which establishes dark skin colour as a signifier of lower class, lower caste and South Indian identity rooted in biological difference and essentialism. Furthermore, colourism in modern India is a highly gendered phenomenon. Due to normalisation of white beauty ideals by media and racialised capitalist economies in the present-day globalised Indian society, the awareness of the inadequacy of dark skin in a colourist society moulds their positionality and ways of knowing in a similar process to how race builds unique lived experience. -

List of 65Th Filmfare Award Winners 2020 – Download PDF Here

List of 65th Filmfare Award Winners 2020 – Download PDF Here letsstudytogether.co/list-of-filmfare-award-winners-pdf Filmfare Award 2020 Winners – List of 65th Filmfare Award Winners PDF 65th Filmfare Awards 2020 Winners PDF. The 65th Filmfare Awards ceremony, presented by The Times Group, honored the best Indian Hindi-language films of 2019. The 65th Filmfare Awards event was held on the 15th of February 2020 at Indira Gandhi Athletic Stadium, Guwahati. This is the first time in six decades that a Filmfare Award ceremony was held outside Mumbai. Karan Johar and Vicky Kaushal were hosts of the award ceremony. Congratulations to all the winners of the 65th Flimfare Awards 2020. Here is the full list of winners, best actors, films, short films, singers and many more. List of Filmfare Award Winners PDF – Alia Bhatt and Ranveer Singh-starrer Gully Boy won big at the awards. While Ranveer took home the Best Actor’s trophy for his performance in the film, Alia won the Best Actor in a Leading Role (Female) for the same film. List of 65th Filmfare Award Winners The event was hosted by Karan Johar, Varun Dhawan and Vicky Kaushal. The awards are presented to honour both artistic and technical excellence. A curtain raiser ceremony was held in Mumbai on 2 February 2020, which honoured the winners of technical and short film awards. In the same function, the nominations for popular awards were also announced. Actress Neha Dhupia was the host of this ceremony. Complete List of 65th Filmfare Award Winners Award Category Name of the Winner Movie Best