Confused Auteurism. What Has Adoor Gopalakrishnan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

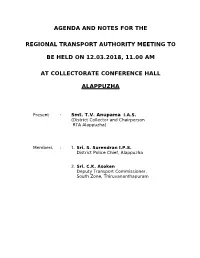

Agenda and Notes for the Regional Transport

AGENDA AND NOTES FOR THE REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY MEETING TO BE HELD ON 12.03.2018, 11.00 AM AT COLLECTORATE CONFERENCE HALL ALAPPUZHA Present : Smt. T.V. Anupama I.A.S. (District Collector and Chairperson RTA Alappuzha) Members : 1. Sri. S. Surendran I.P.S. District Police Chief, Alappuzha 2. Sri. C.K. Asoken Deputy Transport Commissioner. South Zone, Thiruvananthapuram Item No. : 01 Ref. No. : G/47041/2017/A Agenda :- To reconsider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-15/9612 on the route Mannancherry – Alappuzha Railway Station via Jetty for 5 years reg. This is an adjourned item of the RTA held on 27.11.2017. Applicant :- The District Transport Ofcer, Alappuzha. Proposed Timings Mannancherry Jetty Alappuzha Railway Station A D P A D 6.02 6.27 6.42 7.26 7.01 6.46 7.37 8.02 8.17 8.58 8.33 8.18 9.13 9.38 9.53 10.38 10.13 9.58 10.46 11.11 11.26 12.24 11.59 11.44 12.41 1.06 1.21 2.49 2.24 2.09 3.02 3.27 3.42 4.46 4.21 4.06 5.19 5.44 5.59 7.05 6.40 6.25 7.14 7.39 7.54 8.48 (Halt) 8.23 8.08 Item No. : 02 Ref. No. G/54623/2017/A Agenda :- To consider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of a suitable stage carriage on the route Chengannur – Pandalam via Madathumpadi – Puliyoor – Kulickanpalam - Cheriyanadu - Kollakadavu – Kizhakke Jn. -

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

Document Edit Form

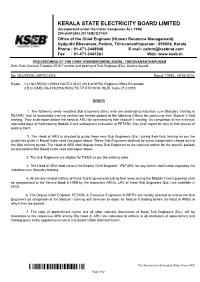

KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD LIMITED (Incorporated under the Indian Companies Act, 1956) CIN-U40100KL2011SGCO27424 Office of the Chief Engineer (Human Resource Management) Vydyuthi Bhavanam, Pattom, Thiruvananthapuram - 695004, Kerala Phone : 91-471-2448948 E-mail: [email protected] Fax : 91-471-2441361 Web: www.kseb.in. PROCEEDINGS OF THE CHIEF ENGINEER(HRM) KSEBL, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Sub:-Estt:-General Transfer 2018-Transfer and posting of Sub Engineer(Ele)- Orders issued. No. EB2/SE(Ele.)/KPSC/2018 Dated, TVPM., 29-06-2018 Read:- 1.Lr.NO.REIII(I)1459/14 DATED 03.02.2018 of KPSC Regional Office Ernakulam 2.B.O (CMD) No.819/2018(HRD).7/ILTP-STP/2018-19) Dt.Tvpm 27.3.2018 ORDER 1. The following newly recruited Sub Engineers (Ele.) who are undergoing Induction cum Statutory training at PETARC and its associated training centers are hereby posted to the following Offices for continuing their Module II field training. They shall report before the head of ARU for commencing their Module II training. On completion of the minimum stipulated days of field training Module II and subsequent evaluation at PETARC they shall report for duty in their places of posting itself. 2. The Head of ARU is directed to guide these new Sub Engineers (Ele.) during their field training as per the guidelines given in Board Order read 2nd paper above. These Sub Engineers shall not be given independent charge during the field training period. The Head of ARU shall depute these Sub Engineers to the required station for the specific periods as stipulated in the Board Order read 2nd paper above. -

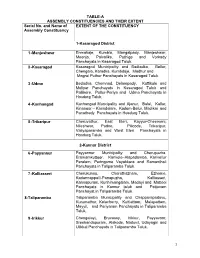

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

May 2013 India Review Ambassador’S PAGE America Needs More High-Skilled Worker Visas a Generous Visa Policy for Highly Skilled Workers Would Help Everyone

A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. May 1, 2013 I India RevieI w Vol. 9 Issue 5 www.indianembassy.org IMFC Finance Ministers and Bank Governors during a photo-op at the IMF Headquarters in Washington, D.C. on April 20. Overseas capital best protected in India — Finance Minister P. Chidambaram n India announces n scientist U.R. Rao n Pran honored incentives to boost inducted into with Dadasaheb exports Satellite Hall of Fame Phalke award Ambassador’s PAGE India is ready for U.S. natural gas There is ample evidence that the U.S. economy will benefit if LNG exports are increased he relationship between India and the United States is vibrant and growing. Near its T heart is the subject of energy — how to use and secure it in the cleanest, most efficient way possible. The India-U.S. Energy Dialogue, established in 2005, has allowed our two countries to engage on many issues. Yet as India’s energy needs con - tinue to rise and the U.S. looks to expand the marketplace for its vast cache of energy resources, our partner - ship stands to be strengthened even facilities and ports to distribute it macroeconomic scenarios, and under further. globally. every one of them the U.S. economy Despite the global economic slow - There is a significant potential for would experience a net benefit if LNG down, India’s economy has grown at a U.S. exports of LNG to grow expo - exports were increased. relatively brisk pace over the past five nentially. So far, however, while all ter - A boost in LNG exports would have years and India is now the world’s minals in the U.S. -

A Study on Computer Graphics & Animation in Film

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 03 Issue: 11 | Nov-2016 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 A STUDY ON COMPUTER GRAPHICS & ANIMATION IN FILM MEDIA B. Senthil Kumar1, D. Nivedhitha2, Col. Manoj Kumar3, Ayem Perumal4, M.R. Chitra Mai5 1Researcher, Indian Institute of Industry Interaction Education & Research, India 2Associate Professor & Head, Dept, of Mass Communication, Pondicherry 3Research Scholar, Pondicherry University 4Quality Control Manager, NSH, Kuwait 5Research Scholar, CSJM University, India -----------------------------------------------------------------------***------------------------------------------------------------------------ Abstract – The main aim of this research article is to study the impact of computer graphics and animation in film media. In this f a s t d e v e l o p i n g i n f o r m a t i o n society computer graphics and animation has become the most important communication tool. The development of the film media and the progress of computer graphics and animation are intimately related to each other in many ways. The film media not only provide information and entertainment, but they also provide directly and indirectly many opportunities to the unemployed people in India. Every year, thousands of films are released with computer graphics and animation. Multibillion film projects are now very common in India. Computer graphics and visual effects are now becoming the part of all cinema projects. Even though 3D animated film and ordinary commercial film has differed, the visual effects are common. Many famous Indian film directors have used visual effects to communicate their dream effectively. Computer graphics have impact on the target audience, fuel to our knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Documentation Kerala

DDOOCCUUMMEENNTTAATTIIOONN KKEERRAALLAA An index to articles in journals/periodicals available in the Legislature Library Vol. 11 (3) July – September 2016 SECRETARIAT OF THE KERALA LEGISLATURE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM DOCUMENTATION KERALA An index to articles in journals/periodicals available in the Legislature Library Vol.11 (3) July to September 2016 Compiled by G. Maryleela, Chief Librarian V. Lekha, Librarian Preetha Rani K.R., Deputy Librarian Denny.M.X, Catalogue Assistant Type setting Sindhu.B BapJw \nbak`m sse{_dnbn e`yamb {][m\s¸« B\pImenI {]kn²oIcW§fn h¶n-«pÅ teJ-\-§-fn \n¶pw kmamPnIÀ¡v {]tbmP\{]Zhpw ImenI {]m[m\yapÅXpambh sXc-sª-Sp¯v X¿m-dm-¡nb Hcp kqNnIbmWv ""tUm¡psatâj³ tIcf'' F¶ ss{Xamk {]kn²oIcWw. aebmf `mjbnepw Cw¥ojnepapÅ teJ\§fpsS kqNnI hnjbmSnØm\¯n c−v `mK§fmbn DÄs¸Sp¯nbn«p−v. Cw¥ojv A£camem {Ia¯n {]tXyI "hnjbkqNnI' aq¶mw `mK¯pw tNÀ¯n«p−v. \nbak`m kmamPnIÀ¡v hnhn[ hnjb§fn IqSp-X At\z-jWw \S-¯m³ Cu teJ\kqNnI klmbIcamIpsa¶v IcpXp¶p. Cu {]kn²oIcWs¯¡pdn¨pÅ kmamPnIcpsS A`n{]mb§fpw \nÀt±i§fpw kzm-KXw sN¿p¶p. hn.-sI. _m_p-{]-Imiv sk{I«dn tIcf \nbak`. CONT ENTS Pages Malayalam Section 01-34 English Section 35-52 Index 53-79 PART I MALAYALAM Agriculture 6. If ]dn¨v tIcfw ]mS-¯n-d-§p- t¼mÄ 1. lnµp-Xz-hm-Zn-I-fpsS hnI-k-\- ]n.-sI. kp[m-I-c³ ¯nsâ s]mÅ-¯cw ka-Im-enI ae-bmfw, 1 BKÌv 2016, AÀ¨\m {]kmZv t]Pv 48þ50 Nn´, 23 sk]vXw-_À 2016, Iq«m-bva-bp-sSbpw ]mc-kv]-cy-¯n-sâbpw t]Pv 38-þ40 kmaq-lnI PohnXw hos−-Sp-¡m\pw ImÀjnI {]Xn-k-Ôn-tbbpw hÀ²n-¨p- A´-tÊmsS Irjn-¡m-c\p Pohn-¡m\pw h-cp¶ Bß-l-Xy-tbbpw Ipdn-¨pÅ Ign-bp¶ tIc-f-amWv s\ÂIrjn teJ-\w. -

Iconographies of Urban Masculinity: Reading “Flex Boards” in an Indian City

Iconographies of Urban Masculinity: Reading “Flex Boards” in an Indian City By Madhura Lohokare, Shiv Nadar University Asia Pacific Perspectives v15n1. Online Article Introduction On an unusually warm evening in early May of 2012 I rode my scooter along the congested lanes of Moti Peth1 on my way to “Shelar galli,2” a working-class neighborhood in the western Indian city of Pune, where I had been conducting my doctoral field research for the preceding fifteen months. As I parked my scooter at one end of the small stretch of road that formed the axis of the neighborhood, it was impossible to miss a thirty-foot-tall billboard looming above the narrow lane at its other end. I was, by now, familiar with the presence of “flex” boards, as they were popularly known, as these boards crowded the city’s visual and material landscape. However, the flex board in Shelar galli that evening was striking, given its sheer size and the way in which it seemed to dwarf the neighborhood with its height (see figure 1.1). Figure 1.1 Flex board marking the occasion of Mohanlal’s birthday, erected in Shelar Galli, Pune (Photo by author) The image of Mohanlal Shitole, a resident of Shelar galli, dressed in a bright red turban and a starched white shirt, with a thick gold bracelet resting on his wrist, stood along the entire length of the flex making it seem like he was towering above the narrow lane itself. The rest of the space was dotted with faces of a host of local politicians (all men, barring one woman councilor) and (male) residents of the neighborhood, on whose behalf collective birthday greetings for Mohanlal were printed on top of the flex.