Political Comedy and Its Effect on Tolerance and Trust by Cecilia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

200 Bail Posted by Hamerlinck

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 1988 2-19-1988 Daily Eastern News: February 19, 1988 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1988_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 19, 1988" (1988). February. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1988_feb/14 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1988 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern Illinois University I Charleston, I No. Two�t;ons. Pages Ul 61-920 Vol 73, 104 / 24 200 bail posfour felonies andte each ared punishable by Wednesday. Hamerlinck brakes at the accident scene. "He with a maximum of one to three years Hamerlinck recorded a .18 alcohol (White) had cuts all over and hit his sophomore Timothy in prison. level. Johnson said the automatic head on the windshield. I'm sure a lot of erlinck, who was arrested Wed Novak said a preliminary appearance maximum allowable level is .10. If a the blood loss he suffered was from his ay morning in connection with a hearing has been set for Hamerlinck at person is arrested and presumed to be head injury." and run accident that injured two 8:30 a.m. Feb. 29 in the Coles County intoxicated, they could be charged with Victims of the accident are still .nts, posted $200 bail Thursday Jail's court room. driving under the influence even if attempting to recover both physically oon and was released from the Charleston Police Chief Maurice their blood alcohol level is below .10, and emotionally after they were hit by County JaiL Johnson said police officers in four Johnson added. -

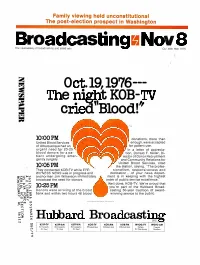

Broadcasting O Ov

Family viewing held unconstitutional The post -election prospect in Washington Broadcasting o The newsweekly of ov broadcasting and allied arts Our 46th Year 1976 Oct.19, 1976--- The night KOB -TV cried Blood!' 10:00 PM donations, more than United Blood Services enough, were accepted of Albuquerque had an for patient use. urgent need fpr 20 -25 In a letter of apprecia- blood donors for a pa- tion, Donald F, Keller, Di- tient undergoing emer- rector of Donor Recruitment gency surgery. and Community Relations for United Blood Services, cited 10:05 PM the station, saying, "The profes- They contacted KOB -TV while EYE- sionalism, responsiveness and WITNESS NEWS was in progress and dedication...of your news depart- anchorman Jim Wilkerson immediately ment is in keeping with the highest broadcast the need for donors. order of public service excellence." Well done, KOB -TV. We're proud that 10:25 PM you're part of the Hubbard Broad- Donors were arriving at the blood casting 50 -year tradition of award - bank and within two hours 46 blood winning service to the public. n-< unneo Bwod Sarwes of aouaue, cue rmDNm Hubbard Broadcasting KSTP -TV KSTP -AM KSTP -FM KOB -TV KOB-AM KOLFM WTOG -TV WGTO -AM Minneapolis. Minneopolis Minneapolis- Albuquerque Albuquerque Albuquerque Tempo. Cypress Sr. Paul St. Paul Sr. Paul St. Pe burp Gardens MagicT stogy. 61 ri:11°1 yPou've probably heard about Greater new leadership by Pulse (Mar -May '7 Media's Magic Music Then: "Sold Out" city! programming by now. Now all's well at Greater Medi, They tell us it's the Right? first brand -new idea in music Well, yes. -

Broadcasting Emay 4 the News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol

The prrime time iinsups fort Vail ABC-TV in Los Angeles LWRT in Washington Broadcasting EMay 4 The News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol. 100 No. 18 50th Year 1981 m Katz. The best. The First Yea Of Broadcasting 1959 o PAGE 83 COPYRIGHT 0 1981 IA T COMMUNICATIONS CO Afready sok t RELUON PEOPLE... Abilene-Sweetwater . 65,000 Diary we elt Raleigh-Durham 246,000 Albany, Georgia 81,000 Rapid City 39,000 Albany-Schenectady- Reno 30,000 Troy 232,000 Richmond 206,000 Albuquerque 136,000 Roanoke-Lynchberg 236,000 Alexandria, LA 57,000 Detroit 642,000 Laredo 19,000 Rochester, NY 143,000 Alexandria, MN' 25,000 Dothan 62,000 Las Vegas 45,000 Rochester-Mason City- Alpena 11,000 Dubuque 18,000 Laurel-Hattiesburg 6,000 Austin 75,000 Amarillo 81,000 Duluth-Superior 107,000 Lexington 142,000 Rockford 109,000 Anchorage 27,000 El Centro-Yuma 13,000 Lima 21,000 Roswell 30,000 Anniston 27,000 El Paso 78,000 Lincoln-Hastings- Sacramento-Stockton 235,000 Ardmore-Ada 49,000 Elmira 32,000 Kearney 162,000 St. Joseph 30,000 Atlanta 605,000 Erie 71,000 Little Rock 197,000 St. Louis 409,000 Augusta 88,000 Eugene 34,000 Los Angeles 1 306,000 Salinas-Monterey 59,000 Austin, TX 84,000 Eureka 17,000 Louisville 277,000 Salisbury 30,000 Bakersfield 36,000 Evansville 117,000 Lubbock 78,000 Salt Lake City 188,000 Baltimore 299,000 Fargo 129,000 Macon 109,000 San Angelo 22,000 Bangor 68,000 Farmington 5,000 Madison 98,000 San Antonio 199,000 Baton Rouge 138,000 Flagstaff 11,000 Mankato 30,000 San Diego 252,000 Beaumont-Port Arthur 96,000 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City 201,000 Marquette 44,000 San Francisco 542,000 Bend 8,000 Florence, SC 89,000 McAllen-Brownsville Santa Barbara- (LRGV) 54,000 Billings 47,000 Ft. -

TV GUOIDE 01992 TV Listing Inc

Thursday, February 25, 1993 ESSAYONS, "Let Us Try" Section C Page 1 PULL OUT FEB RUARY 27, 1993 I SATURIIA TV Listings TV GUOIDE 01992 TV Listing Inc. FtWorth,TX MORNING FOR ESSAYOHS READERS 5AM 5.30 6AM 6:30 7AM 730 8AM 8:30 9AM 9:30 10 AM 10:30 11 AM 11:30 KOEB Lifestyles of fhe Rich & King Arthur Conan,the JimHenson's Bobby's World Tom& Jerry Eeklhe Cat TinyToons TAZ-MANIA X-Meo SuperDave WCWWorld Wide Wrestling Famous Adventurer DogCity Kids KMIZ OttAir A PupNamed MooMesa GoofTroop AddamsFai- BogsBunny Tweefy Show Laod Scoohy Doo & of the Darkwing Dock Wionie Pooh ABCWeekend ly Losf Specials KOIR (3:30)Home Shopping PaidProgram Fievel'sAmer- Mermaid Gartleldaod Friends TeeoageMuantNioja Turtles TeeoNet Disey's Raw AmazingLive Backto the , IcanTails Toonage SeaMonkeys Future KOZK OftAlr Learnto Read LearntoRead SewingWifh Sewing uilting From GrahamKerr's Computer CiaoItalia! Victory Garden r_ _Nancy the Heartland Kitchen Chronices KRCG OttAir Mr. Bogus Capt.Planet Flevel'sAmer- Mermaid Garfieldand Friends TeenageMutant Ninja Turtles can Tails Notlust News Disney's Raw AmazingLive Grimmy CCC Tonnage Sea Monkeys KSPR OfttAir Beakman's Capt.Planet A PupNamed MooMesa Goof Troop AddamsFam- BugsBunny & TweetyShow Landof the DarkwingDuck Beakman's Billy Packer -k 00World Scooby Don ily Lost World KYTY OttAir Weekend U.S.Farm NotJust News Today Savedby the California MarkBerosen NBAInside CollegeBasketball 9r TravelUpdate Report Bell Dreams Stuff WWOR PaidProgram PaidProgram EdMcMahon's StarSearch *+-91: *e A&E Fugitive NewWider- Toucha SharkTerror: Danger Beach Time MachineWith Jack J. EdgarHoover Investigative Reports American Spies ness Child's Life Perkins Justice Science CNN uayureae Correspond. -

July/August 2012

Join Us on Summer 2012 Newsletter of The Press Club of Cleveland From the President Collins, Diadiun, Goodman, Henry, Warner to Enter Ed Byers Press Club of Cleveland Journalism Hall of Fame As you can see, we Jack Marschall to Receive 2012 Heaton Award have combined our July and August editions into a single summer of 2012 edition. So, there is much catching up to do from our May edition and, first off, I want to say ‘thank you’ to Lee Moran and her hardworking Excellence in Journalism Collins Diadiun Goodman Henry Warner committee for the annual June awards program that just keeps getting better Jim Collins, Ted Diadiun, Vivian Since 1996, Vivian Goodman is a report- and better, year after year. Goodman, Vern Henry and Stuart Warner er, producer and host of the award-winning Giving out several hundred awards in have been selected by Press Club members radio news programs Fresh Air and All such a relatively short amount of time for induction into The Press Club of Things Considered broadcast on WKSU- is no small task and everyone continues Cleveland’s Journalism Hall of Fame. Jack FM, Kent State University. Goodman began to marvel at how quickly we do it and Marschall was chosen by The Press Club her award-winning WKSU stint in 1996. how the event has evolved over the years, as the recipient of the 2012 Chuck Heaton A Cleveland resident, Goodman has been becoming the premier journalism awards Award. (More on Marschall on page 7.) chosen by the Cleveland Association of event in the state of Ohio. -

1987 News & Newsmakers Revisited

Memorial of 1987 Local Athletes made o C ^ Dearly Departed 1987 Sports History See page 4 See page 11 COLOMA * HARTFORD»WATERVLIET , THE TRI-CITY RECORDecembeDr Vol. 103-No. 52 ARROW EDITION OF THE " RECORD^ 30, 1987 1987 News & Newsmakers Revisited Hear Ye! It seems good ol' 1987 is just Hear Ye! getting broke in and here it is time to put it behind us and On this, the brand usher in 1988. While the world of 1987 faced new, grand New Year, war, famine, disaster and we extend our calamity the Tri-City area of wishes for peace, Watervliet, Coloma and Hartford hope and friendship had its own heartbreak, heart- throughout fhe world. ache, joy and hopes. The follow- ing is a look back at 1987 The City of Watervliet pur- Area satellite television through the window of the front chased a 25-acre site from dealers questioned Watervliet We especially value pages of The Tri-City Record. General Mills for $500.00. Township's satellite antenna or- the friendship we dinance. JANUARY... have with you. FEBRUARY... Tests of the Hartford City The City of Watervliet lost its Coloma Township, officials water quality come back bid to block construction of an announce land appraisals are positive. adult foster care home when a Tri-City near completion. Sara Oderkirk Is crowned FIRST LADY AWARD... judge ruled the City's objections Kelly Sinclair is named Miss Miss Coloma. Miss Thyra Jennings of were unfounded. The City ob- Hartford. The Paw Paw Lake-River Ven- Watervliet was a finalist in the jected on the grounds the facili- Developers threaten lawsuit tures urge Governor Blanchard Michigan 150 First Lady Award Record ty was opposed by neighbors in face of Watervliet City's con- to create a project to control fer- Program this past July. -

Annual Report 2013 Board of Directors 4

Annual Report 2013 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 4 COMMITTEES AND TaSK FORCES 5 NABJ AWARDS 6 S.E.E.D PROGraM 10 MEMBERSHIp 14 MEDIA INSTITUTES 15 NABJ ANNUAL CONVENTION 16 FINANCIAL REPORT 18 OUR MISSION The National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) is an organization of journalists, students, and media-related professionals that provides quality programs and services to and advocates on behalf of black journalists worldwide. NABJ is committed to: STRENGTHENING ties among black journalists. SENSITIZING all media to the importance of fairness in the workplace for black journalists. EXPANDING job opportunities and recruiting activities for veteran, young and aspiring black journalists, while providing continued professional development and training. INCREASING the number of black journalists in management positions and encouraging black journalists to become entrepreneurs. FOSTERING an exemplary group of professionals that honors excellence and outstanding achievements by black journalists, and outstanding achievement in the media industry as a whole, particularly when it comes to providing balanced coverage of the black community and society at large. PARTNERING with high schools and colleges to identify and encourage black students to become journalists and to diversify faculties and related curriculum. PROVIDING informational and training services to the general public. 2 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BLACK JOURNALISTS Founded by 44 men and women on December 12, 1975, in Washington, D.C., NABJ is the largest organization of journalists of color in the nation. Many of NABJ’s members also belong to one of the dozens of professional and student chapters that serve black journalists nationwide. NABJ Member Benefits: ACCESS to year-round professional development through the NABJ Media Institute, the annual convention and career fair and regional conferences. -

Wednesday Morning, Nov. 28

WEDNESDAY MORNING, NOV. 28 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Betty White; Reality Live! With Kelly and Michael (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Show Roundup. (N) (cc) (TV14) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Phil McGraw; Chris Mann. (N) (cc) The Jeff Probst Show (cc) (TV14) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Cookie Monster Daniel Tiger’s Sid the Science WordWorld (TVY) Barney & Friends 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) can’t resist cookies. (TVY) Neighborhood Kid (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Better (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 Paid Tomorrow’s World Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Zula Patrol (cc) Pearlie (TVY7) 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVG) (TVY) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Joseph Prince This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Alive With Kong Against All Odds Pro-Claim (cc) Behind the Joyce Meyer Life Today With Today With Mari- 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (cc) (TVG) Scenes (cc) James Robison lyn & Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) The Steve Wilkos Show Mother’s The Bill Cunningham Show My Fam- Jerry Springer (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show Mother’s 32/KRCW 3 3 much-younger boyfriend. -

09/01/2013 Contact: Ryan Mccarthy/Julia Mays at 941-955-7676

NEWS RELEASE Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall 777 N Tamiami Trl Sarasota, FL 34236 For Immediate Release: 09/01/2013 Contact: Ryan McCarthy/Julia Mays at 941-955-7676 THE STARS SHINE THE BRIGHTEST IN THE VAN WEZEL’S 2013-2014 SEASON! Sarasota, FL – Single tickets go ON SALE Saturday, September 7 at 10 AM at the Box Office, online, and by phone! Appointments are available for ticket buyers by calling the Box Office at 941-953-3368. Living up to its reputation as the #1 Performing Arts Hall of its size in North America (Venues Today, 2000 seat category), the Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall is primed and ready to bring yet another star studded season to Sarasota! The 2013-2014 lineup includes music icons such as Michael McDonald, Yanni, Wynton Marsalis, Katharine McPhee, Merle Haggard, and Sutton Foster! Returning to the hall, favorites Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons, Vince Gill, and Dave Koz are sure to bring the house down with their extraordinary performances. Comedy legends, new and old alike, include Jay Leno, Jerry Seinfeld, Lewis Black, Ron White, and Bill Cosby to name a few! The Broadway Season sees a number of Sarasota premieres, along with a few fond classics that are near and dear to both Broadway aficionados and new comers. Returning tours include Disney’s Beauty and The Beast, Hello Dolly! starring Sally Struthers, Man of La Mancha, and Mamma Mia! while fresh off Broadway performances include the high energy Green Day’s American Idiot and Million Dollar Quartet, Tony Award for Best Musical winner Memphis. -

Listing (D TMC (Pay) Movies

8-B.THE Page BRUNSWICK BEACON, Thursday, August 25 , 1988 m Atlantic Tolephone Co. Cable 9ATIIRHAY' moi,NING k O Vision Cable Of N.C. VJ I 1 L/ n 1 ' 1M j| «a DM 11. 'Vl.sl.yU itHttv iik mv>tiii n a August 27 O® WWAY 1ml (ABC) Wilmington 6 AM I &30 7 AM 8:30 9 AM 9:30 V I ml "OCT WECT (NBC) Wilmington 7^30 ITAM | | 10 AM | 10:30 11 AM | 11:30 " n I lH WUNJ (PBS) Wilmington WW AY A 0DO« WJKA (CBS) Wilmington PQffl Pugs Twwty' WlMrils l\us! l\|i NVmstw I llo.ti GUtsfbustns Soul Tiaa» ; _ BrACO QP WBTW * (CBS) Florence. SC TO loiim* All (!J WTVD (ABC) Durham lUndcnJog llVvKy Isnufs Alon Fiagjle A/cines k Uf 0 30 ARTS, A&E, New York WUNJ ft Mg OUT Sesame Street Sesame Street lixKxv irtfci Ioslo of Attv Kowts Yixr lltvitth M.whjih) Mradcs A CBN. Virginia Beach cob i»/ O® ESPN. Sports. NY Happening Gl Joe Jem Kitty I Mwj a MW (D 00 NICK. Nickelodeon. NY ^JKA Kdsongs SV^1 IVe Woo Mty Mouse Uustn' T & T ID U TBS (Ind.) Atlanta WBTWCnxA little «BJRW B(W House Mty I tabesIVe Woo Mly Mouse Fopcyo Dennis 16R® TNN. Nashville USCTl USA. New York VHYD KxJsongs Crack ops Rascals lh*v WVanJs l\*«xl Minister I stones © WGN (Ind.) Chicago Yang h|» Heal GUtstUisliis Soiil Trail W WWOR (Ind ) New York ARTS (4 CO) Storioc* Holmes / BlutWI C t\U*S ftrotas Suruva WV! I .i Ocflo I 3? LIFE. -

1963 Television Quarterly

TELEVISION MBER 3 QUARTERLY Published by The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences with the cooperation oftheTelevisionand Radio Center of Syracuse University twice as much Cronkite twice as much news (in a new half-hour format) Beginning September 2, CBS News-Evening Edition, with the Peabody Award -winning correspondent Walter Cronkiteas anchor -man and man- aging editor, will be increased from 15 to 30 minutes Monday through Friday on the CBS Television Network. This expanded broadcast will enable the world-wide facilities of CBS News to cover many more of the day's stories in greater depth on CBS NEWS -EVENING EDITION WITHWALTER CRONKITE. TELEVISION QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES Published by The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences in cooperation with the Syracuse University Television and Radio Center A. WILLIAM BLUEM: EDITOR Syracuse University RICHARD AVERSON Assistant Editor EDITORIAL BOARD MAX WYLIE WALTER CRONKITE Chairman Co -Chairman JACQUELINE BABBIN HERMAN LAND KENNETH G. BARTLETT LAWRENCE LAURENT ROYAL E. BLAKEMAN FRANK MARX EVELYN F. BURKEY RICHARD M. PACK LAWRENCE CRESHKOFF HUBBELL ROBINSON SYDNEY H. EIGES GILBERT SELDES EUGENE S. FOSTER ROBERT LEWIS SHAYON DAN JENKINS WILLIAM TREVARTHEN HAL DAVIS PETER Corr Director of Advertising Business Manager DESIGN Syracuse University Design Center TELEVISION QUARTERLY is published quarterly by The National Academy of Television Arts and Sci- ences in cooperation with the Syracuse UniversityTelevisionand Radio Center. EDITORIAL OFFICE: Television and Radio Center, Syracuse University, Syra- cuse, New York. All advertising copy and editorial matter should be sent to that address. BUSINESS OFFICE: Advertising place- ment and other business arrangements should be made with the New York office of The National Academy of Tel- evision Arts and Sciences, 54 West 40th St., New York 18, New York. -

No Peace in Panama

It.'-.' Saturday, Feb. 27, 1988 Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm 30 Cents NO PEACE IN PANAMA By Reid G. Miller and because of that I call for The Assocloted Press national resistance to paralyze the entire country starting PANAMA CITY, Panama - Monday." Ousted President Eric Arturo The opposition National Civic Delvalle called Friday night for a Crusade on Friday evening called national strike to show that for a “progressive, nationwide Panamanians repudiate the lead strike” starting immediately. ership of Gen. ManOel Antonio Aurelio Barrilla, president of Noriega. the Panamanian Chamber ol The general accused the United Commerce and Industry, one o States of instigating Delvalle’s the groups in the coalition, saiu failed effort on Thursday to end the Crusade was seeking “total his military rule and said Wa paralysis’ ’ of the country by early shington waged a campaign of “psychological warfare" against next week. him. However, only one of several Noriega addressed a rally of his strikes called last summer by the supporters Friday night and said coalition of about 200 organiza Panamanians who consider “be tions was notably successful, and trayal, because they are bom the government has shut down traitors, meet a bad end here.” I opposition newspapers, radio and Up to 10,000 people attended the {television stations, limiting the rally at the central garrison of the Crusade’s ability to spread its Defense Forces. message. The Noriega-dominated Na In his address at the central tional Assembly turned Delvalle garrison rally, Noriega said, a ' out of office in a 10-minute session early Friday after the president “The Defense Forces offer subor tried to fire the armed forces dination, total support and our chief following Noriega’s indict cooperation to the new president, ment in the United States as a our heat efforts to be able to reach dmg trafficker.